The figurine is clearly a vital part to cursing, healing or changing the subject, but the societal structure and ceremony are equally crucial. Who is allowed to use the doll? What rituals take place at the same time?

The Voodoo doll:

The use of a gris-gris begins by a private visit to a Voodoo Queen or Doctor, and ends with a ceremony. The Voodoo Queen or Doctor, after having understood what the client desired, invokes the spirits for guidance. Every Voodoo Queen or Doctor in Louisiana possesses a real snake, which represents the physical incarnation of the spirit Legba. To attract him, one uses chicken, tobacco and bones. Without Legba's guidance, the Voodoo Queen or Doctor cannot construct a doll or even instruct on a doll's construction. Once the doll has been constructed, the only remaining steps are to physically make it similar to the targeted person-- by attaching a strand of hair, for instance-- and hide it in the immediate vicinity of the targeted person.

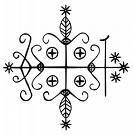

This is the veve, or religious symbol, of the Papa Legba:

The actions during a private seance are contingent on what type of aim it has.

- Love: After the required invocation of Legba, the spirit of Aida Quiedo is most often invoked. She is the primary female spirit and love is assigned to the female in Voodoo religion. In Louisiana, the deceased Voodoo Queen of New Orleans, Marie Laveaux, who has now become a spirit, is often called upon, because Lavaux was famed for her love potions during her life. To bring the spirits into the doll, one must encircle it with things known to attract and draw the attention of the spirit. This is very contingent on the Voodoo Queen or Doctor, and can have many different constructions. However, in general, pink-- which attracts love spirits-- and red-- which defines attraction in sexual terms-- are used. Other associations with love are perfurmes, rose petals, sweets, plums, feathers and bright objects.

- Power and Domination:Legba is invoked, and St. Jude (the patron of lost causes) and St. Anthony (the patron of finding lost things) are also called upon. To do this, purple or green candles are often used, and mint or cinnamon aromas are burnt. If one is seeking to harm an opponent, the Ghédé spirits are invoked, because they are considered easily corruptible. To attract a Ghédé spirit, one may use the fresh blood from a bird, silver coins or a knotted string.

- Luck and Finance: There is no specific spirit for welfare, the Voodoo Queen or Doctor would normally try to attract a spirit the client is familiar with. To do this, parsley is used. It can be sewn into the gris-gris, thus altering the doll directly, or around it. If gambling is concerned, lodestones (raw magnetic rocks) are wrapped in currency and deposited into the doll's pouch or into the doll itself. Gold or yellow is associated with money, not green.

- Uncrossing: If someone wants to undo a malevolent gris-gris that is acting against them, they must invoke Legba. Before the ritual takes place, sweeping one's front steps every morning with the dust of red bricks serves as a protection against evil spirits.

A monetary payment is required for the Voodoo Queen or Doctor, and a spiritual payment is needed for the spirit. This spiritual paymet is voluntary posession by the spirit, and occurs during a Voodoo ceremony, after a gris-gris has begun its work. The ceremonies have no fixed rules, but often begin with prayer. The spirit of Legba is invoked, and small offerings are made to the spirits. Rythmic music begins, and grows louder and faster until posession occurs. Jerry Gandolfo, who has attended many of these ceremonies, recounts how they often unfold: "The spirits are invited to possess the people in attendance. A spirit is not confined to time or place, however there are several things a mortal can do that a spirit would not normally experience. These include eating, drinking, dancing, singing, smoking and sexual relations. The person who has used the gris-gris, or doll, and has received favorable intercession of the sprits invites the spirit to posses them in order to use their physical bodies as a means to engage in the aforementioned activities."

The Minkisi:

In 1915, a BaKongo convert to Christianity, Kavuna Simon, describes the ritual undertaken for the Na Kongo (a water Nkondi) in his etnographic notebook. A sick man has visited an nganga for help to cure a presumed hernia:

"For treatment, the patient goes to a crossroads and sits down, stretching out his legs in the direction of the setting sun. The nganga places a stone on a ring of nsonya grass and puts the medicine bag of the nkisi on it. He opens the bag and begins to massage the patient, first marking him with red and white on his cheeks, forehead, and arms and tying a little raffia bracelet on one forearm. He raises one of the patient's arms, stretching and squeezing it, claps his hands and says, "Heal the king's man. Knock down trees, do not knock down us people, lord Na Kongo, eh, ri -ri -ri -ri, restrict, release.Seize pigs, seize chickens, seize goats, do not seize us people, see?" As he massages the whole body he says, "Go rest, go rest." He intones the song, "I trod on the cane cutter, I trod on the rat, I was in trouble, I cannot speak of it. O Mother Nkusu, yes, I trod on the cane-cutter rodent and the rat; women with hernia, men with hernia, I did not see them."

Much of this ritual is not comprehensible to a modern, Western audience, especially the deeply poetic and metaphorical chant of the nganga. The symbolism of this whole ritual is present in every detail. Firstly, the crossroads symbolize the intersection where spirits arrive to visit the living. The legs of the patient face the setting sun, which marks the boundary between the land of the living and the land of the dead. The patient hopes to send his illness into death, which is where it orginated. Interestingly, the patient is painted red and white to resemble the Nkisi-- not the opposite. This seems to indicate that an Nkisi cannot be played with to resemble a human, it is the human which must modify itself to suit the Nkisi. Because the human must adapt to the figurine, the Nkisi is clearly much mmore powerful than the person, which fundamentally increases its agency and importance. In this case, the color white symbolizes the other world (Mpemba) and the red acts as a mediator between the world of the dead and the one of the living, because it is the color of the sunrise and sunset. The bracelet attached to the patient's arm acts as a protection from any undesirable forces.

The Nganga's complex invocation refers to the Nkisi as King. The reference to trees is a warning to the spirits not to confuse a tree with a human, as the two are viewed similarly in BaKongo proverbs and rituals. Rodents and referred to due to the holes they claw, and the nganga is asking the Nkondi not to confuse those with graves. The whole ritual is extremely dramatic and literary, and states the demanded solution quite clearly amid the poetic terms.

Importance of the nganga, or chief:

For the BaKongo, there is very little difference between the chief and the nkisi doll. This fascinating blur between human and thing occurs because both are attributed the power of containing spirits. This is exemplified through language, where the chief, called nganga, can also be called minkisi. Alfred Gell criticizes the frequent Western assumption that any culture who does not clearly differentiate between thing and human is archaic. "If philosophers have a hard time pin-pointing exactly what makes the difference between human persons engaging in 'actions' and mere things obeying causal laws then we are in a better position to understand why some people appear to be (contextually) indifferent to this distinction." Gell is, of course, not arguing that distinction between humans and things do not exist, but rather stating that we do not know how to precisely define that difference. He presses this point further by arguing that one knows an idol, like a Voodoo doll or a Nkisi, is not a person, but defining the reasons why prooves to be hard. To Gell, the idol's strength is that it defies categorization-- it is neither a person, nor a miraculous machine, but rather a God.

Back to The Voodoo doll