|

Micro-Historical Perspectives on Moral Choice: Case Studies from Early Modern Portugal Joaquim de Carvalho

Keywords

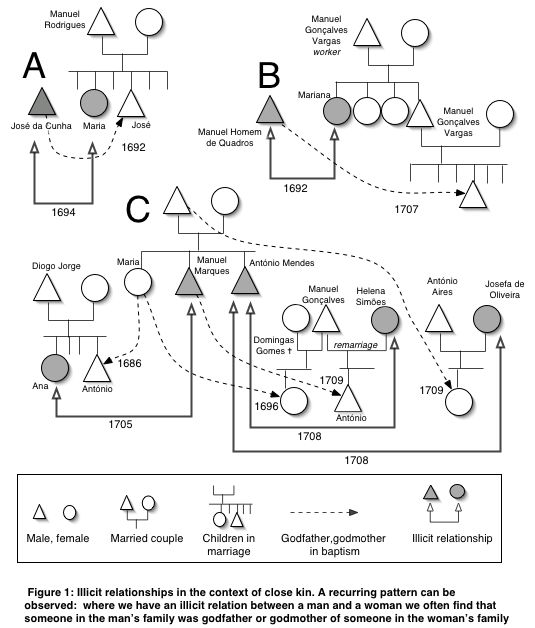

Introduction The study of moral conformism in past populations is an important field for the comprehension of pre-industrial societies, especially in the area of demographic behavior. To pose the problem succinctly, the existence of the European Marriage Pattern, characterized by late marriage and high levels of definitive celibacy, implies that past populations had the capacity to control sexual behavior in the period between puberty and late marriage (Hajnal, 1965). The most cost-efficient way to control the behavior of millions of persons was to have them believe that it was fundamentally wrong to engage in sexual activities before marriage and thus obtain the self-control and restraint necessary for the late marriage system to work as a regulator of demographic growth, in an epoch when contraception was not diffused. Moral conformism was therefore an integral part of pre-industrial societies. Church and civil authorities provided the concepts, control and repression necessary to shape individual behavior in the necessary direction. Industrialization would melt the cement that held together this self-regulating mechanism. Free from the economic, social and mental constraints of traditional peasant societies, the new generations adopted behaviors that made illegitimacy ratios increase all over Europe, until the decline of fertility brought by contraception (Shorter, 1975). It has been argued that a significant part of the immoral behavior that did occur in pre-industrial Portugal was in fact part of a process that had marriage as the ultimate goal (Laslett, 1980a: 1-65). Couples would engage in sexual contact in contexts where they were hoping that a marriage would follow and abstain in other circumstances. This would explain the mysterious relationship between nuptiality and illegitimacy: the more intense the marriage activity the more illegitimate births occurred because the probability of a couple having sex was linked to the perceived probability that marriage was possible, thus increasing competition between candidates, while if marriage was difficult due to economic circumstances couples would abstain from risky behavior, resulting in low nuptiality and low illegitimacy. There is strong statistical evidence to support this (Schellekens, Jona, 1995). But many situations of illegitimacy cannot be traced to courtship practices, nor can pre-nuptial relations be considered a widespread behavior across all social strata. This leads to a central question: was there a “bastardy prone sub society”, or, in other words, can moral misconduct be linked to specific social groups (Laslett, 1980b)? We examine these questions with a micro-historical approach that is intended to look in detail into cases of immoral sexual behavior that have reached us through documentation from the ecclesiastical judiciary. Our purpose is to inquire into moral choice among individuals in an Early Modern Portuguese parish. Our starting point is the cases of moral misbehavior brought before episcopal justice during episcopal visitations. We then retrace the persons involved through a variety of sources, the most relevant of which are the parish registers. As much biographical and relational information as possible was collected to shed light on the context in which the observed behavior took place. The results are, for some of the cases, detailed biographies and networks of relations that provide insights into patterns of behavior and allow us to gain unexpected perspectives on individual and group strategies. The close-up view of individual trajectories and networks does not fit easily into the macro-level explanatory framework outlined above. As with other micro-historical studies, it is hard to find the great causal mechanisms of history at work and the problem of articulating micro and macro level explanations becomes central. Defining and assessing moral conformism Episcopal visitations (Visitas Pastorais) in Portugal provide abundant source material for studying moral behavior. For centuries, the episcopal visitors traveled to the most remote parishes of Portuguese dioceses and, with great ceremony, would gather the population together, select a number of them, seemingly at random, and ask them, under oath and threat of excommunication, to denounce the public sinners they knew of. The transcripts of these interrogations, sometimes full of exuberant detail, have survived in large numbers in the diocese of Coimbra, and are known as devassas, from the juridical term applied to an inquiry that is undertaken without prior knowledge that a crime has been committed. It is a unique form of documentation, as far as we know, in the European context, mainly because of its ex officio nature and the random nature of the interrogations (Carvalho 1990). The uniqueness of the Visitas Pastorais in Portugal, far from being the bureaucratic and administrative exercise they became in other countries, can be traced to a jurisdictional division of labor, between the bishops and secular judiciary. A series of circumstances and political contexts developing the reception of the Tridentine decrees in Portugal created the figure of the mixti fiori case, a crime that simultaneously fell under ecclesiastical and secular jurisdiction and that was to be handled by the juridical system that first learned of the event. Among these, moral cases were, for many decades, the most frequently denounced. Within this category, we find mainly illicit relationships, couples living together or having occasional intercourse without being married, but also prostitution, encouraging or facilitating prostitution (panderism), and consenting to the immoral behavior of those under one’s responsibility (e.g. parents allowing the misbehavior of daughters). Note that other more relevant moral or sexual crimes, such as bigamy or sodomy, were not within the jurisdiction of the episcopal courts, but rather came under the compass of the Inquisition. The jurisdictional context and the ritualized practice of the visitation imply that the question of the definition of moral behavior can be taken for granted. Individuals would know which practices were being targeted by ecclesiastical justice. The list of cases that would be subject to interrogation during the visitation was announced at mass on the previous Sunday and the list would be posted on the church door, according to ecclesiastical manuals. We also know from the transcripts that people denouncing cases mentioned that the guilty parties had been caught in previous visitations, whenever that was the case. In fact, the whole point of the devassa was to find out, through interrogation of randomly selected persons, what was believed to be wrong in the parish. Central to the content and form of the episcopal visitation was the idea of public sinners, those that publicly defied the accepted norms of behavior. The public sinners were a danger to the salvation of the souls of their fellow parishioners because the spectacle of unpunished crime drove the spectators to misbehave themselves. So, public sins required public punishment, and that was the main purpose of the devassa, also called the “temporal visitation” From our point of view, it is relevant to note that the people we will be talking about had a clear awareness of the normative position of their behavior. They were neither involuntary sinners, nor people without a clear awareness of the fact that they were doing wrong. They were fully aware of the normative significance of their behavior and so they consequently constitute a significant sample for the inquiry into the logic of moral choice. Methodology The episcopal visitations were the sources that provided us with the original cases to explore. But the essence of the methodology used relied on the cross-linking of information from various origins, with parish registers playing a major role as providers of biographical fragments. The cases analyzed in this study are thus based on information from episcopal visitations, parish registers, notarial records, varied documentation related to the Santa Casa da Misericórdia, marriage processes (normally brought about by impediments raised to marriages banns) and municipal sources. Although the time frame of the series varied according to the source type, the greatest concentration of information was found for the period from 1680 to 1720, and our cases are located inside that time frame. The various sources were introduced into a nominal database managed by specially designed software, which allowed for the reconstruction of individual biographies and the analysis of networks of relations (Carvalho, 1997: 287-536). The methodology has since been used in other studies with similarly rewarding results (Castiço, 2003, Ribeiro, 2003). The setting: Soure, a Portuguese parish in the eighteenth century Soure is a parish in the center of Portugal, 30 kilometers south of Coimbra, which is the see of the diocese. The population numbered around 3000 in the mid-18th century. Until the 19th century, Soure was also a municipality (concelho), with a significant set of local offices in military and civil administration. There was also a parish chapter (colegiada) with six clergymen (beneficiados). The parish covered a considerable area by the standards of the center of Portugal: around 90 square kilometers. Two rivers cut across the territory, running South to North, joining together and merging into the Mondego river to the north of the parish. Most of the parish is thus a secondary system of gentle valleys that reproduce the great plain of the Mondego on a smaller scale, forming some of Portugal’s more fertile land. The region consists of a series of gentle hills, rarely over 100 meters high and separated by the wide valleys of the rivers and their offshoots. Down in the plains, the land is of excellent quality, fertilized by periodic floods, which, despite being considerably disruptive of everyday life, leave behind a nutrient-rich deposit that in some places allows for the continuous cultivation of crops without the normal rotational fallow period. Hamlets were scattered midway between the river plain and the pine forests that crowned the hills. The population was highly dispersed in these small agglomerates: we found almost 500 toponymical forms for inhabited places inside the parish in the 17th and 18th-century sources. This territory was donated to the Knights Templar in 1128, at a time when Portugal was yet to be born as a nation. Soure was part of the frontier of Christianity in the 12th century and it was the Templars’ first base in the West of the Iberian Peninsula. The Templars subsequently received jurisdiction and land from the Portuguese kings, which they completed through acquisition and exchanges with other seigniorial lords. With the extinction of the Templars, the land and the acquired rights were transferred to the Portuguese Ordem de Cristo, which progressively gravitated to the king’s direct control. From the 16th century onwards, the original Templar possessions in Soure became resources that the Portuguese kings used to reward services or ensure loyalties. Together with the possessions of other former military orders, they constituted an essential element of the monarch’s policy under the name of comendas. Comendas would be given to the nobility in exchange for distinguished services, especially those related to the overseas affairs of the kingdom. It is important to understand that a comenda was not, is this context, a clear physical entity composed of land and associated structures. It was rather a patchwork of rights, taxes, pieces of land, percentages on production, means of production such as mills or waterworks, brought together on an ad hoc basis, seemingly with the sole objective of constituting a round total of revenue that had to be awarded at some moment in time. In this setting, we can distinguish several modes of resource appropriation that help us to understand the main social strata. At the first level, we find those who appropriated the prime resources generated by the comendas: the comendadores. These were typically non-resident members of the administrative nobility who received comendas in Soure as payment for services rendered or loyalty shown to the king. Soure’s resources would often be part of a larger package that would add up to the amount awarded for a particular service. This meant that the comendadores had a very distant relationship with the community: they did not live there; there was hardly any trace of their physical presence in the territory. They collected their income through intermediaries, rendeiros, who might in turn further hire out to local residents the complex work of levying the rights, dues and taxes. The rendeiros offered the comendador a fixed cash amount for the comenda. Their profit was proportional to their ability to collect as much as possible from the peasants living within the bounds of the comenda. This social and geographical distance of the comendadores created a space for a local elite. At this second level, we find families with seigniorial mansions as their main residence. They were locally based and Soure played an important role in their long-term strategies. Their economic ambitions were centered on occupying the posts of the local administration, enjoying ecclesiastical careers and engaging in traditional landowning with related income from rents. The exercise of prestigious local positions was important, not just because of the income they provided and, sometimes, the exemptions and other privileges associated with them, but also because this activity strengthened the inclusion of those that held these positions amongst the restricted set of those that governed a governança. A significant number of the holders of these positions therefore obtained degrees from the University of Coimbra that allowed them to serve in both the local and, hopefully, central administrations. Others entered holy orders because their families were thus able to obtain ecclesiastical sources of income, either through influence or by direct right of nomination. Amongst the more important of these, we can find some families from the local nobility, not very far removed in status from the comendadores (they might have their own comendas elsewhere): these people stayed for long periods in Lisbon in the royal entourage and kept themselves at a distance from local administrative tasks, except, occasionally, for the specific role of provedor da Misericórdia (head of the local charitable institution). But most of them were really locally based, extending their sphere of influence through marriage outside the municipality. Just below the local elite belonging to the governança we find wealthy farmers (lavradores), who managed to send their sons into holy orders and, occasionally, to marry their daughters into the local nobility. Some of these farmers were closely related to the collection of rents and taxes of the comendas and played an important role in the social networks through which resources flowed. Below them, we find the laborers (seareiros, trabalhadores de enxada), and poor farmers, who provided the underlying labor force. Artisans and local commerce existed on a limited scale (barbers, blacksmiths, carpenters, pharmacists/boticas, tailors, shoemakers) with individuals often combining some sort of agricultural economic activity with the exercise of a craft or trade. Of some specific importance in terms of resource flow were the " almocreves”, men that transported goods on carts or horseback and constituted a well-defined group inside the community. The cases Our set of case studies is based on a number of illicit couples denounced in the course of episcopal visitations. Some cases stand on their own; others form a cluster of situations with recurrent patterns of behavior. In all the cases, the cross-linking of sources and the reconstruction of networks allowed for insights into strategies that involved immoral behavior, either at the individual level or as part of what seem to be shared strategies in some social groups. Concubines and Godfathers, resources and immorality Our first example attempts to clarify a recurrent pattern that emerges when reconstructing the network that existed around some illicit couples: where we have an illicit relationship between a man and a woman we often find that someone in the man’s family was godfather or godmother to someone in the woman’s family. This interesting phenomenon allows us to propose that immoral behavior can be understood as part of wider relational strategies that allowed for the flow of resources between different social groups. Figure 1 shows couples involved in concubinage and adultery in the context of their immediate kin. It also shows spiritual kinship ties created in baptism through the “godfathering” or “godmothering” of children. Locating the illicit couples (gray symbols connected by U-shaped arrows) and the “godparenthood” relations (dotted lines) should make the pattern easily observable.

These spiritual kinship relations have a specific direction: they always connect a godfather or godmother in the family of the man involved in the illicit relationship to a child in the family of his female partner. It is important to note this fact because the reverse never happens: we never find a person in the family of a woman involved in an illicit relationship who is either godfather or godmother to someone in her lover’s family. To make the pattern clear, let us go through the three networks shown in Figure 1, describing the underlying cases. Case A involves José da Cunha, a married man from a well-known family of the community, and Maria, the daughter of Manuel Rodrigues, the barber of the small hamlet close to Jose’s house. They were denounced during the visitation of 1694. Neighbors declared that he was frequently seen in the barber’s house at night, making a loud noise with guitars, the reason for this behavior being Maria. There were rumors that she was pregnant with his child and had decided of her own free will to leave for Lisbon (Carvalho, 1997: 53-107). When the case was brought to the attention of the visitador in 1694, the witnesses were describing events that had occurred some time earlier, one or two years before, probably. In 1692, José was godfather to Maria’s most recent brother, named José after the godfather. The presence of José da Cunha at the baptism of the young José is either contemporary to the affair he was having with Maria or it could be, if we accept some historical guesswork, the event that triggered Jose’s interest. Obviously we will never know, but the point is not the role of this baptism in the sequence of events that originated an illicit relationship. The point is rather the topos, the simultaneous presence of an illicit couple and a kinship relation of that type. As we move to other cases, we see that the details vary greatly but that a basic pattern emerges. Moving to case B, we see the same structural pattern in another situation, which is very different in its details. In 1692, António Cordeiro and his wife Francisca Nunes (not shown in Figure 1) were denounced for panderism. They “provided” women to various men of the community in their own house or in the residence of the clients. Men named by the witnesses included wealthy and important persons of Soure. Among the witnesses, there appears a certain Maria de Jesus, aged 22, telling a strange story: her sister, Madalena, was abducted by António Cordeiro and taken to Manuel Homem de Quadros, a member of the local gentry, with whom she remained for 11 or 12 days. Cordeiro broke a lock of a door behind which Madalena’s father had shut Madalena, “to avoid her being deceived (enganada)”. Another sister of Madalena and Maria de Jesus, named Juliana, who also testified in the devassa, confirmed these facts. The visitador then called the father of the three girls, Manuel Gonçalves Vargas, who confirmed the disappearance of his daughter for a period of time but carefully avoided direct denunciation of either António Cordeiro or Manuel Homem de Quadros, saying that he had heard those names in relation to the girl’s absence but could not remember from whom he had heard them, and that he had no further information. He stated his profession as a laborer (trabalhador) and could hardly write his name at the bottom of the testimony. Why was Madalena locked up by her father? Because it was not the first time she had been involved in scandal and denunciations in visitations. In 1686, six years before the episode of the broken lock, Madalena had been denounced as a woman of bad behavior (mal procedida) and promiscuous relations (devassa do seu corpo). Six years later, her father kept her locked inside the house, but in vain. We know that we are, again, confronted with a situation of social imbalance. Manuel Homem de Quadros belonged to one of the families of the local gentry. He was single at the time of his involvement with Madalena and had registered an illegitimate child from another girl shortly before that. Soon afterwards, in 1693, he was to marry a woman of good family and become one of the more prominent men of Soure. Just like José da Cunha in the previous case, this was a case of a young male from an important family found engaging in illicit relations with women of a lower status. We can find no trace of spiritual kinship between Manuel Homem de Quadros and Madalena’s family before the case appeared in the devassa. But we find the link later on. Madalena had a brother, with the same name as their father: Manuel Gonçalves Vargas. Manuel is an interesting case of social mobility (analyzed in Carvalho, 1997: 139-150). He was to nurture a close relationship with another important family of Soure, the Soares Coelho family, and under their patronage succeed in accessing increasingly elevated posts in local administration. Manuel chose the godparents of his seven children carefully, consolidating a network of spiritual kinship with the Soares Coelho family, present at every one of their baptisms. But he occasionally diversified his alliances and selected Manuel Homem de Quadros as godfather to his son, António, in 1707. The person alleged to have entertained his sister for 12 days in 1692 became the spiritual kin of Manuel. So, here the pattern assumes the following form: a man involved in an illicit relationship with a woman was godfather to her nephew. Case C provides more complex variants of the same theme. Two brothers, Manuel Marques and António Mendes, were involved with three women, two of them married. The denunciations occurred in 1705 (Manuel) and 1708 (António). Manuel and António’s family was part of the local governança and the two young men played an important role in the collection of the comendas’ income. We find here the complex network of dependencies that emerged around the collection of the comendas’ rents on behalf of the comendadores. António was the rendeiro of one of the comendas and his brother had close relations with other rendeiros, one of whom was godfather to his illegitimate son. On the other side of the illicit relationship, we have women who were the daughters or wives of almocreves and laborers. Almocreves and laborers would naturally be employed by the rendeiro to collect and transport the goods that constituted the rents. Factual information on this is found in the denunciations: António Mendes, rendeiro, was accused of sending Manuel Gonçalves, almocreve, to do business on his behalf, so that he (António Mendes) could illicitly visit the wife of Manuel Gonçalves without difficulty. We find in our sources varied traces of the networks that connected rendeiros, almocreves and plain trabalhadores de enxada (hoers). It was through these networks that the drainage of the local resources towards the absent comendadores occurred. But the outward flow of resources coincided with a counter flow in which the rendeiros got their share of the rents, and paid the almocreves and the laborers. Their contract with the comendadores would have set a fixed amount of money. If they collected more, it was their profit; if they collected less, it might spell ruin. So it was crucial to collect and sell: that was where laborers and almocreves became crucial. The business of collecting rents was a hazardous one. Every year the comendadores could put up new contracts, asking for new bids from rendeiros. The profitability of the process was closely dependent on unpredictable natural, and sometimes social, events. Efficiency in collecting the fruits of the land and selling them quickly was crucial for the rendeiros, and hence their dependency on a network of reliable almocreves and trabalhadores. The former, on the other hand, could not afford to be left out of the circuit and would naturally cherish good relations with the latter. It is a fragment of these networks that we have captured in case C of Figure 1. Again, spiritual kinship is found between the families of the persons involved in concubinage and adultery. Again, the direction of the spiritual kinship is the same: someone in the close family of the manis godfather or godmother to a child in the close family of the woman. We see an overlap between the spiritual kinship network and the flow of resources. “Godfatherhood” and “godmotherhood” go in the same direction as the part of the rents that stays in the community, what we could call the “local margin”. Women in concubinage and adultery move in the opposite direction. This is more than just an elaborate way to say that affluent men attracted, or forced themselves upon, women in economic need. The fact that spiritual kinship links matched the flow of resources and the provision of women for illicit relations introduced a dimension of symmetry or reciprocity. We take it for granted that asking someone to be the godfather or godmother of one’s child was a voluntary act that arose from the desire to formalize an existing relationship or to propitiate a desired one. We also take it for granted and proved by the available data, that no one chose as godfather or godmother to their child someone that they considered of inferior status. It was either a horizontal choice or an “upward-looking choice”. This is a pattern that we find in several countries and epochs (Gunnlaugsson and Guttormsson, 2000; Ericsson, 2000), but not everywhere at all times. For instance, in Renaissance Florence, it was the other way around (Haas, 1995). So the bond that was created or reinforced in that way was a voluntary expression of relative social positioning. In a way, the father of the child was saying to the family from which he was asking for a godparent: “we know that we are less than you are and therefore we put ourselves under your protection by offering our services.” The traditional ritual of saluting a godfather, by kissing his hand and asking for benediction, was clearly a symbol of submission (Silva, 1989: 866). Used in this way, spiritual kinship could be considered a compensating phenomenon, that diminished social distances by creating a link of protection and dependency (Calliert-Boisvert, 1968: 99). The channel that was thus opened was bi-directional: there was value or gratification flowing in both directions. There was obviously no causal relationship between spiritual kinship and illicit relations. They were both expressions of a reciprocal process by which actors at different levels in the social hierarchy established channels that propitiated an exchange of resources. If we consider the nature of the illicit relations that we have before us in the context of the recurrent pattern of reciprocal flows, we must conclude that “morality” was not really a central concern here. What was happening at the moral level was closely linked to the fabric of social strategies in the struggle to obtain the best possible position in networks through which resources flowed. To sin or not to sin: a tale of two sisters The previous examples and their context seem to point to a socially determined behavior regarding sexual mores: men from higher social strata engaged in relationships with women of lower status and the context seems to indicate that these relationships were part of a plethora of reciprocal exchanges. In our interpretation, however, it is rather the way an immoral behavior was used as part of an overall strategy that is relevant. The social imbalance of the people involved constitutes one specific background, among others, against which strategies were deployed. We can find illicit relations as a strategy in socially horizontal situations. The case we are about to present is apparently a confirmation of Laslett’s “courtship hypothesis”, but at the same time it suggests that the same social and family context can produce very different behavior. The case consists of a triangular relationship between a José Rodrigues, Josefa Espírito Santo and Maria Francisca. José had promised to marry Josefa, but changed his mind and decided to wed Maria instead. The story reaches us through the legal proceeding started by Josefa to prevent José from marrying the other girl in 1716(Arquivo da Universidade de Coimbra, Processos de casamento, José Rodrigues e Maria Francisca, 1716). She came forward with a complaint made on the basis of "public honesty". Her argument was that José had publicly promised to marry her, not Maria. By failing to keep his promises, he was obliged to compensate her, as stipulated by Canon Law (Bride, 1965). The episode is interesting for our argument for two reasons: firstly because we obtain from the process, mainly through Josefa’s own testimony, an insight into how sexual activity was associated with the process leading to marriage; secondly, by reconstructing Josefa’s social background, we gain an understanding of the constraints that led Josefa to fall into José's seductive trap. According to Josefa’s allegations in the case, José had promised marriage to her and with that promise had had "all he wanted" from her ("teve dela o que quiz”). Witnesses heard in the inquiry declared that they knew they had an illicit relationship, using the expression "tracto illícito”. No one actually witnessed the promise of marriage but it was assumed that marriage was what the couple had in mind because they were "both equal in blood and wealth". Although José denied ever making promises to Josefa, another witness stated that “it was understood that if they had copulated with one another the plaintiff would not have consented [to that] without a promise of marriage”. Josefa described her relationship with José to the parish priest who was registering the complaint. She talked about how she believed José, how she had given herself to him, how he would come and go from her house as he wanted. She also detailed the successive excuses that José gave to delay the promised marriage: “he said he didn’t have a proper coat and needed to borrow money from an uncle to buy one”; months later “he said the price of grain was too high”, and so on. It is hard to avoid the thought, just by reading the transcript, that one believes what one wants to believe. The marriage process does not give much information about the context of Josefa or José. But by cross-linking it with other sources we are able to reconstruct enough fragments of Josefa’s life. Josefa’s father died in 1700 when Josefa was 14. She had a younger sister named Joana, who was 11 at the time. In 1712, Joana applied for the dowry of the Misericórdia, a prize of 15,000 réisthat the confraternity awarded each year to a female orphan of poor origin in order to facilitate her marriage. She got the dowry and married that same year, at the age of 23. Josefa remained single at the age of 26. Four years went by and Josefa was still unmarried. She would never get the dowry of the Misericórdia for herself because the confraternity would not give twice to the same family. So the fortune of her sister was, in a way, her misfortune. When José appeared in her life, she was a poor woman, aged 30, whose chances of marriage were quickly disappearing. She believed José’s promises and accepted pre-marital sex clearly because in her mind, and in the minds of her neighbors who came to testify, it cemented the bond and made the promise stronger. This case is illustrative of the factors that affect moral choice in two areas. The first one relates to the social environment of the actors involved. Both Joana and Josefa had the same social position. They shared the same difficulties, needs and constraints. But their trajectory was very different from the point of view of an observer of moral behavior. One followed the path of virtue, marrying, with the pious dowry, in the church of the Misericórdia, where no other marriages took place. Josefa, on the other hand, was seduced and abandoned, sinning publicly and confessing everything to the priest after hearing the announcement of her misfortune in the banns of another girl’s marriage. Yet, as individuals, they were doing the same thing: fighting against the curse of celibacy inexorably attracted by poor orphan girls. We can think of them as interchangeable, if chance had decreed otherwise: if Josefa had gotten the dowry, maybe Joana would have ended up with the alternative of less than strict morals. The second factor that it is interesting to note is how institutions like the Misericórdia and the church courts operated in this environment. The dowry of the Misericórdia is seen here to fulfil its role perfectly: by endowing orphan girls they would preserve their virtue and keep them away from sin. The dowry seems to have been created in a social context in which the upper class, which created the dowry by donation, was fully aware of what lay in store for a poor orphan girl in terms of a strategy for survival. Their virtue was at stake and the cases we have described so far fully confirm this: immoral behavior was an integral part of strategies that bridged the gap between classes and allowed for some flow of resources towards the more needy. The betrothal and the related impeachment of “public honesty” was also a strategy to secure acceptable moral behavior in a context of late marriage, where conformity to moral rules required a very long period of sexual abstinence and a related risk of remaining single. The betrothal reduced the risk associated with the late age of marriage, by creating a commitment between two persons who were not able to marry, normally for economic reasons. It also provided a setting where some forms of intimacy might occur more easily, but our impression here is that pre-marital sex occurred in contexts where marriage was believed to be imminent. The view from above: the toleration of immoral behavior in the upper classes In the cases above that linked spiritual kinship to immoral behavior, we not only obtained insights into the relational strategies of the lower social groups, but also formed the impression that social inequalities were exploited by men from wealthy families in order to obtain sexual favors. It is important to mention now that this type of behavior did not seem to meet with any significant condemnation from inside the “community”. Evidence shows that instead it amounted to public, and indeed not infrequent, behavior. One of the most striking examples of how, up to a point, the immoral conduct of an upper-class man was accepted by his family was the case of José da Cunha (mentioned above in another context) and Isabel Rodrigues. Their relationship left a long trail in the sources, from their initial denunciation in a visitation of 1692 to their final sentencing to imprisonment in 1737. José was a member of the local nobility and Isabel, the daughter of a laborer, was designated a “poor girl” in the sources. In 1692, José was denounced for keeping Isabel in a house at his own expense, “with all that is necessary”, for more than 6 years. They were both single at the time and had baptized a child in 1691, with José acknowledging paternity. As we have seen before, José was involved in other cases around that time. José married Inês Galvão de Melo, the daughter of a member of the governança in 1693, shortly after his first incrimination with Isabel. But his behavior did not change with marriage and, as we have seen above, he was denounced in the visitation of 1694 for his relationship with Maria, the daughter of the local barber. He was also denounced again in the same visitation for continuing his relationship with Isabel, “who he keeps at hand in some houses of his, close to this estate, at his expense, buying her clothes, shoes, everything she needs…’ In the visitation of September 1694, the witnesses talked about the existence of three children of the couple, and one Jorge Luís informed the visitador that “the accused is said to have arranged for her marriage with a kinsman of hers and was obtaining a dispensation in Rome for that purpose”. We can confirm the denunciations of an eminent “arranged” marriage for Isabel. In the parish registers, we find that Isabel married a certain António Francisco, a few months later, on December 22nd, 1694. And we also find that Isabel married pregnant with a child that would be baptized on May 8th, 1695, and that the father of the child was José da Cunha. He had baptized his first legitimate child two months before in March of the same year. So, Isabel was five months pregnant with José’s child when she married António in December 1694. The interesting point here is that José assumed paternity in the child’s baptismal register. This implies that the purpose of the arranged marriage was not to conceal the relationship, which would have been the main priority in England at that time (Quaife, 1979: 104-123). But even more striking are the names of the other people present at the baptism of this illegitimate child of two married persons: the godmother was D. Maria da Cunha, the mother of José da Cunha, and the priest who celebrated the act was Teodósio Mendes, the brother of José’s wife.1 Teodósio was not the vicar of the parish and just took part in ceremonies involving closely related kin, at the commission of the vicar. It was also he who had baptized José’s legitimate child two months earlier. In the same spirit of non-concealment of the true nature of the relations involved, a distinguished member of José’s family, D. Tomás de Moscoso, was witness to the arranged marriage between Isabel and António. From 1695 onwards, José and Inês, on the one hand, and Isabel and António, on the other, baptized successive children, with there being no confusion about Antonio’s paternity, at least in the baptism records. The next visitations brought no further denunciations. But, behind the apparent normality, we have occasional evidence that the distance between the two worlds was not that great. In 1700, José would be a witness to the marriages of Catarina and Manuel, Isabel’s sister and brother. And we know almost for certain that they were together at least once at the baptism of the illegitimate child of a foreign couple, in September, 1707, when Isabel was the godmother and Rodrigo, the 12 year-old son of José and Inês, was the godfather. The story of José and Isabel does not end here. In 1708, they were widowed within a few months of each other. And a troubled new period of their lives began because they decided to marry, a decision that would trigger an impeachment process from both José’s family and his late wife’s relatives. One of his nephews and his father-in-law came forward when the banns were published saying that the marriage was impossible because it was incestuous. The argument of the impeachment was that José had fornicated with one of Isabel’s sisters and also with Isabel’s mother. If this was true, there was incest in the first degree of affinity, raising an impediment that prevented the marriage. The case was long and full of episodes, but it is clear that José and Isabel had openly resumed their relationship (if they had ever really interrupted it). They were not able to marry because the ecclesiastical court decided against them. The case became public and they were denounced again in the visitations of 1712 and 1713. In 1718, another striking event left its mark in the parish registers: a son of José and Isabel, named João Homem da Cunha, married a girl who was the godchild of his father. The new couple had a child five months after marriage. José and Isabel were now grandparents. The interesting point is that the godfather of this child would be José’s legitimate son, Manuel. Again José closes the circle, using spiritual kinship to knit his two separate worlds closer together. We find José and Isabel still being denounced in 1736, 44 years after the first time that their story had been registered in a devassa. In 1737, the Episcopal Court aggregated all the accumulated sins and sentenced both of them to be expelled from Soure, she to Miranda in the north-east and he to the Algarve in the extreme south. They could not be further apart now, and at this point we lose them from our sources. There are many interesting dimensions in this long story, very much abbreviated here, but the one that most interests us is the way in which José and Isabel were integrated into the social networks to which they belonged. We have seen the family of José participating in acts relating to his parallel life with Isabel and symmetrically José and his relatives being present as godparents and witnesses at baptisms and marriages of Isabel’s family. We have seen not only José’s family but also his wife’s family involved in ceremonies related to his other immoral life. In all this, we find no sign of condemnation or distancing from the “community”. Punishment comes from the outside world, through the visitations. The problems started with the attempted marriage. It was not the illicit relationship that was a problem; it was the idea of making it legitimate that was scandalous. José’s lawyer, in the impeachment process, would argue that by marrying Isabel he was saving his soul and repairing the great damage he had done to her honor and virtue over the years. But that virtuous interpretation was certainly completely irrelevant to José’s family and to the family of his late wife. To make sense of this, one has to look into the legal framework regulating the transmission of property inside and outside marriage (for an overview in English, see Brettell, 1991). In Portugal, unless otherwise established by pre-nuptial agreement, there was community of property in a marriage and everything brought into it, and all that was acquired afterwards, became the joint property of the couple. Each of the spouses could dispose freely of a third of his/her half of the common property to donate or leave in a will. The other two thirds would be divided between the existing children or, in the absence of these, amongst the next of kin. When one of the spouses died, the surviving one remained as head of the household, managing the common property, distributing the half corresponding to the deceased amongst the respective heirs. (Ordenações Filipinas, liv. IV, tit. XLVI, XCV). The law also regulated the transmission of property either to concubines (barregãs in the terminology of the Ordenações) or to illegitimate offspring. If a married man transmitted any type of good to a woman (as a gift, donation, sale or by any other means – presumed thefts were also contemplated) with whom he had afeição carnal (carnal affection), his legitimate wife had the right to demand the return of the good, which would then become her own private and full property (Ordenações Filipinas, liv. IV, tit. LXVI). Illegitimate children counted as heirs only if their father was a peão (foot soldier, not a knight). If the father was a noble (cavaleiro / knight), illegitimate offspring had no rights, except if, in the absence of any legitimate heirs, their father named them in his will (liv. IV, tit. XCII). To circumvent this disposition it was necessary to ask the king to legitimate a natural son. The law also considered that children born out of wedlock could be legitimated a posteriori if their parents married after their birth, with implications for inheritance purposes, at least of property donated by the king (liv. 2, tit. 35, par. 12). In this context, the upper-class families that were considered to be of noble condition, like the ones mentioned above, risked little with their men’s immoral behavior. Bastards were out of the line of succession, and any significant gifts to the concubines could be reclaimed by the legitimate wife or her heirs. This explains the apparent tolerance of José’s family towards Isabel. And it also explains why the marriage between José and Isabel was unacceptable. The daughter of the laborer from Sobral would not inherit from the da Cunha family. But the solution must be found inside the same ideological framework that allowed two adults to marry of their own free will. The impeachment of affinity by illicit copulation was easy to insinuate, since it required no more than a few witnesses. The church thus became an instrument of family strategies. José's relationship with Isabel was not atypical. We find several other examples of members of the elite and the governança involved with women of lower status. A very similar situation occurred around 1688 with Sebastião Machado da Costa, later a vereador (member of the municipal council) and commissar of the Inquisition. He was denounced together with a certain Mariana do Rosário, who married another man while maintaining her relationship with Sebastião. According to a witness to the devassa of 1688, Mariana’s husband ended up leaving the parish. We saw before António Mendes and Manuel Marques, the sons of another vereador, having illegitimate children and adulterous affairs. Manuel Homem de Quadros, later provedor of the Misericórdia, had an illegitimate child before marriage. In one spectacular example of moral cynicism, another provedor of the Misericórdia, D. Pedro de Meneses, was denounced in 1694 for buying the virginity of a girl from her father, a poor seasonal migrant worker, for 15,000 réis, claiming that it was the same amount as the dowry that the Misericórdias gave to orphan girls. He took the girl for a couple of weeks and then returned her home. One has to admire the razor-sharp reasoning: by taking away her virginity he was destroying her chances of future marriage, so a good estimate of the value of what was lost was the amount locally given to girls that no one wanted to marry in order to make them acceptable brides (Carvalho, 1997: 125-137). From the testimony in the devassas, and especially the fact that those men actually recognized their illegitimate children at baptism, we infer that their behavior was not hidden from the public. On the contrary, it was not far from being ostentatious, with the women often being placed in houses belonging to their lovers, and clearly showing off their material comfort to their neighbors. From the men’s perspective, this could be a way to assert their status and manhood and to ensure that they had descendants, who might be absent from a future marriage arranged by the family. In a community where inclusion in the ruling elite was based on social recognition, public displays of status and quality were fundamental. From their families’ perspective, it was a situation whose side effects in relation to their interests were closely controlled by law. To the women involved, it was a way out of poverty. Conclusion Putting our findings in the context of a general framework that defines the effect of moral values on sexuality in a pre-industrial society is not an easy task. Like so many micro-historical inquiries, the image that emerges from the reconstruction of individual cases enhances the explanatory value of strategies in a complex network of relations, constraints and personal trajectories and leaves in the dark the larger variables governing the operation of society’s mechanisms. What we see is that moral behavior is one element, among others, of adaptive strategies aimed at achieving the desired outcomes of individuals and families. Similar findings, in the sense that close-up analysis fails to be linked easily with overarching theories of change or social determinism, have been found in studies of illegitimacy in Scotland in the 19th century (Blaikie, 1995), single mothers in Sweden around the same time (Brändström, 1996), and in other aspects related to demographic transition (Schlumbohm, 1996). The relevant conclusion, in our view, is that immoral behavior, as defined by the regularised institution of episcopal visitations, is heavily determined by the social environment, but not in an automatic and simplistic way. The role of institutional, social and economic levels is only comprehensible by reconstructing the actual social networks that surround actors and the ways in which each of the players adapts to the strategies of the others. The focus on strategies and adaptation does not imply that we view our actors as hyper-rationalistic entities, carefully choosing their next moves based on careful assessments of opportunities and threats, weaknesses and strengths. On the contrary, we assume that strategies such as those we describe are behavioral patterns that have developed through adaptation to the social environment. It is easier to enumerate what we did not find. We did not find the “community” as an actor that, for the sake of the common good, imposes rules of behavior and controls compliance with them. As we have seen, understanding the networks of relations is crucial for the interpretation of facts and for postulating hypotheses about motivations and choices. But networks are one thing and the “community”, in the sense that it is often used in the literature (“a territorial group of people with a common mode of living striving for a common objective”, as quoted by Macfarlane, 1977, but see the critique of Calhoun, 1978), is something very different (Wellman and Wetherell, 1996). In other words, in our analysis, we find no instance where it would make sense to use a formulation such as “the community accepted, promoted, denounced, etc… anything”. On the contrary, the community seems to emerge only as an abstraction promoted by external entities, such as episcopal justice, that choose random witnesses to obtain the “community’s” view of local misbehavior. Neither do we see the “community” as a traditional set of values and understandings resisting the externally imposed formalization of law and moral concepts. In Norway, for instance, it has been argued that the traditional concept of marriage as a private contract resisted the formalization brought by the state and the church, and so what were registered as illegitimate births were, from the point of view of the population, the offspring of perfectly acceptable relationships (Sogner 1978). In our examples, it is the contrary that happens. External entities such as the visitador, or the ecclesiastical courts, were used as unwitting partners in personal or family strategies, as we saw in José’s family’s backlash against his marriage plans. If we needed an operational definition of community that is coherent with this perspective, it would be as “a set of people that depend and compete for the same resources, developing mutually adaptive strategies” – and thus close to the concept of a “complex adaptive system” of recent complexity theory (Holland, 1995). We also have difficulty in discussing a “bastardy prone sub society” as a special social group that would be immune to the constraints of “morality”. We rather find “immorality” evenly distributed where it makes sense for individual strategies. The fact that many cases relate to clearly socially unbalanced relations also argues against the idea of a social group with an “endogenous immoral attitude”. In that respect, there are similarities with data from Catholic Ireland in the 19th century (Connolly, 1979). We cannot ignore, of course, that certain combinations of gender and social status contribute in a very powerful way towards the shaping of moral choices. For instance, we find no female member of the elite involved in these cases, neither in Soure nor in the many hundreds of denunciations found in the devassas of other parishes. But again, in our view, this is more easily explained in terms of strategies than in terms of global social determinism: the law allowed parents to disinherit a daughter under 25 years of age who slept with or married an unapproved man (Ordenações, liv. IV, tit. LXXXVIII). So, if you were a potential heiress, there were strong arguments in favor of a strict moral behavior. In more general terms, we believe our results confirm the value of a micro-historical approach to problems that relate to general questions of continuity and change. The cross-linking of different sources and the detailed analysis of the networks that developed around people involved in especially significant cases provided valuable insights into strategies and motivations. But we also subscribe strongly to the idea that such studies should not be hostage to general questions, and should rather profit from the wealth of information available in order to bring forward new dimensions in the questions addressed, as was extensively argued by Magnússon (Magnússon, 2003). As the evidence of the difficulties of articulating the micro and macro levels accumulates, new approaches are required. We argued elsewhere that it is time for history to look to new paradigms coming from the field of Complexity Sciences, where the questions of complexity, adaptation and the emergence of persistent structures are dealt with in frameworks that contain many concepts familiar to the historian and where the problem of interaction between the local and the systemic is central (Carvalho, 1999). Notes 1 The baptism says: Aos outo dias do mes de maio de 1695 baptisou de minha comissão o p.e Theodosio Mendes desta vila a M.a filha de Isabel Rodrigues e de Joseph da Cunha deÇa o qual a mandou baptizar por sua filha forão pp. Fr. Mel Cristovão aqui beneficiado e D.M.a da Cunha m.ora na sua quinta do Sobral e a may desta menina batisada mora no sobra de q fiz este q assignei dia e era ut supra. (On the 8th of May 8th, 1695, baptized by my commision the priest Theodosio Mendes of Soure, commissioned by me, baptized of Soure, Mary, the daughter of Isabel Rodrigues and of Joseph da Cunha de Sá, who had her baptized as his daughter, the godparents were friar Manuel Cristovão, beneficiado [clergyman member of the parish chapter] and Lady Maria da Cunha, living at her farm/estate of Sobral and the mother of this baptized childlives at Sobral, from whichat I made this register, day and month ut supra). A.U.C., Baptismos de Soure, 1681-1720. The true meaning of this simple baptism could easily pass unnoticed if it was not for the cross-linking of sources that allows us to grasp the nature of the relationship between Isabel and José, the fact that the priest was the brother of José’s wife, and Lady that Maria was José’s mother, and also the fact that Isabel had married another man five months beforeearlier. The pieces of this puzzle were scattered in throughout parish registers, genealogies, notarial records, episcopal visitations and in the holy order records of Teodósio Mendes. There is no such thing as irrelevant information. References Blaikie, Andrew (1995). Motivation and motherhood: the past and present attributions in the reconstruction of illegitimacy. Social Review, 43(4): 641-657.

Copyright

2004, ISSN 1645-6432

|

|