|

THE WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION, 1740-1748

The War of Austrian Succession as it played out in North America was essentially fought with local resources as had been the case in the previous two Anglo-French wars. That meant that New England recruits were once again on the front lines. In May, 1744, the governor of the French fortress-city of Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, initiated a new round of hostilities by capturing the New England fishing station at Canso, Nova Scotia.

As on previous occasions, the French raid provoked a New England invasion in retaliation. This time, however, New Englanders had inside information; colonial soldiers who had on earlier occasions been held prisoner at the supposedly impregnable Louisbourg fortress learned its weaknesses, and helped Massachusetts Governor William Shirley plan the successful attack in 1745 by a 4,000 man New England force supported by a Royal Navy squadron of ten men-of-war. The British hoped to extend this victory the following year with an attack on the ever-tantalizing Quebec; on their part, the French planned to retake Louisbourg with a massive fleet of seventy-six ships. But the British fleet didn't sail and the French fleet was destroyed by storms and epidemics. Much to the chagrin of New Englanders, the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, 1748, returned the fortress of Louisbourg to the French.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

New England's Success Against Louisbourg

30. J. Stevens, View of the landing of the New England forces in ye expedition against Cape Breton, 1745, London, ca. 1760.

The provincial force that successfully attacked Louisbourg was a cross-section of nonprofessional soldiers and inexperienced volunteers with little conception of discipline. Overall command of the invasion force was given to General William Pepperrell of Maine and from the start there was a harmony between the soldiers and the officers that was a credit to the leaders of the expedition. Massachusetts and the District of Maine raised 3,250 men, Connecticut 500, New Hampshire 450, while New York sent guns, and Pennsylvania and New Jersey sent money (Rhode Island sent some men as well, but they were late in arriving). The provincial fleet included transport ships and armed vessels with 240 guns; it was supplemented at Canso by a small British squadron of 10 warships and 500 guns. |

|

|

Victory Celebration

31. "A new chart of the coast of New England, Nova Scotia, New France or Canada …" In: The great importance of Cape Breton, London, 1746.

A celebratory dedication and explanatory cartography mark the victory of the New Englanders at Louisbourg. The map itself has a great deal to say—it situates the French fortress on the North Atlantic coast, provides close-up plans of Louisbourg and Quebec and, next to the title cartouche at the lower right, shows the siege in progress.

To the Hon. Wm. Shirley, Esq;

Governor and Captain-General of Massachusetts Bay,

Who projected;

To Sir Wm. Pepperell, Knt. General,

Who commanded;

To Peter Warren, Esq; Admiral,

Who assisted in;

And to all the brave New-England People,

Who served at,The enterprize against Cape Breton |

|

|

The French Point of View

32. Anonymous, Lettre d'un habitant de Louisbourg, Quebec[i.e., Paris], 1745.

Highly critical of French colonial policy, this letter—the only unofficial account of the Louisbourg siege from the French standpoint—was written by an eyewitness to the action and was printed in Paris, not in Quebec as it states on the title page. The anonymous author says that one of the reasons for the French defeat was the low salaries paid to colonial officers, which made it necessary for them to engage in private trade, which in turn made them hold personal interest above national interest and led to distrust between the leaders and their troops. |

|

|

The Fall of Louisbourg Celebrated in Sermon and Poetry

33. Gilbert Tennent, A sermon occasion'd by the success of the late expedition, (under the direction and command of Gen. Pepperel and Com. Warren) in reducing the city and fortress of Louis burgh on Cape-Breton, Philadelphia, [1745].

34. Thomas Prince, A sermon … occasion'd by taking the city of Louisbourg on the isle of Cape-Breton, by New-England soldiers, assisted by a British squadron, Boston, 1745. |

|

|

35. "Victory implor'd for success against the French in America." In: Nathaniel Ames, An astronomical diary … for the year of our Lord Christ 1747, Boston, 1746. |

|

|

The Founding of Halifax

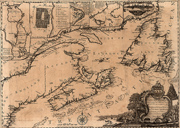

36. James Turner, Chart of the coasts of Nova Scotia and parts adjacent, Boston, [ca. 1750].

Canadian raids against frontier settlements in Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts actually increased after the fall of Louisbourg. In August, 1745, Fort Massachusetts was captured and its garrison taken captive to Canada. Saratoga, New York, was captured and destroyed that same November by a force of Canadians and Indians, and in the winter of 1746-47, a daring raid on Grand Pré, Nova Scotia, overwhelmed a surprised New England garrison. To combat this heightened French threat the British established Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1749. In 1750 James Turner, an English engraver newly arrived in the colonies, satisfied Bostonians' desire to keep up-to-date with unfolding events in the North by publishing this map, a visual handbook for the face-off between New England and New France. Note the cartouche at the lower right, which shows the building of Halifax. The view of Boston at the upper right recalls Thomas Johnston's view of Quebec. |

|

|

Victory Celebration

31. "A new chart of the coast of New England, Nova Scotia, New France or Canada …" In: The great importance of Cape Breton, London, 1746.

A celebratory dedication and explanatory cartography mark the victory of the New Englanders at Louisbourg. The map itself has a great deal to say—it situates the French fortress on the North Atlantic coast, provides close-up plans of Louisbourg and Quebec and, next to the title cartouche at the lower right, shows the siege in progress.

To the Hon. Wm. Shirley, Esq;

Governor and Captain-General of Massachusetts Bay,

Who projected;

To Sir Wm. Pepperell, Knt. General,

Who commanded;

To Peter Warren, Esq; Admiral,

Who assisted in;

And to all the brave New-England People,

Who served at,The enterprize against Cape Breton |

|

| |

The French and Indian War, 1755-1763

The French fur traders, explorers, soldiers, and priests in the wake of Champlain had extended their paths deep into the wilderness, discovering the network of rivers that led to the Mississippi and opened the way to the Gulf of Mexico. This led to visions of an inland trading empire stretching from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the Gulf of Mexico. English traders pushed westward as well through the Appalachians and into the Ohio Valley in search of beaver and otter, and their concerns about French intentions to encircle the English colonies were voiced loudly and urgently. During the course of the previous war with France, the Iroquois had granted the English rights to the Ohio Valley and had pledged to help protect them against the French who were already there. In response, the French expedited plans to push the English back over the mountains by building forts and staging raids on English traders and settlers. William Pitt, the British Secretary of State, decided that the solution was to drive the French out of New France once and for all with three major offensives: the capture of Louisbourg, another move against Quebec, and expeditions against French positions in the Ohio country. Battles of the French and Indian war took place where the French and English confronted one another across contested boundaries; the focus here is on Quebec and Louisbourg, the northern borderlands traditionally at issue between New England and New France. The French and Indian War changed the balance of power between Great Britain and France. When it was over, France had lost North America. |

|

|

Louisbourg Falls Again

37. Captain Ince, A view of Louisburg in North America, taken near the light house when that city was besieged in 1758, London, 1760.

The English expedition against Louisbourg in 1758 consisted of about 10,000 British troops, including colonials, under the command of Sir Jeffrey Amherst. The attack was fiercely resisted by the French, but English cannon doggedly pounded the fortress into rubble and the defenders were forced to surrender after eight weeks. This left the route to Quebec undefended, but it was too late in the season to mount an attack there. Instead, remembering Louisbourg's rise after its first defeat in 1745, the British spent their time leveling the fortress to eliminate any future threat.

By what I could learn when I was among them, they do not fear our numbers, because of our unhappy [internal] divisions, which they deride, and from them expect to conquer us entirely! which may a gracious God in mercy prevent! |

|

Intelligence Gathering

38. Robert Eastburn, A faithful narrative of the many dangers and sufferings … together with some remarks upon the country of Canada, and the religion and policy of its inhabitants, Philadelphia, 1758.

Throughout the course of a century and a half of war and skirmish between the colonists of the northern British colonies and those of New France, numerous settlers and soldiers were captured and taken to Canada, often staying for years as servants or as adopted members of French or Indian families. Those who managed to escape or buy their way out of Canada often returned home and sold their stories, which were read by an eager audience who enjoyed "captivity" tales of all kinds. These stories also provided intelligence about the enemy in Canada—the society and customs of the inhabitants and the state of their defenses and fortifications. |

|

Enlistment Sermon

39. Thaddeus Maccarty, Two Discourses delivered at Worcester, April 5th, 1759, being the day of the publick annual fast, appointed by authority, and the day preceeding the General Muster of the militia throughout the province for the inlisting of soldiers for the intended expedition against Canada, Boston, 1759. |

|

British and Colonial Forces Finally Take Quebec

40. John Bowles, A view of the taking of Quebec, September 13th. 1759, London, [1760].

In the fall of 1759 Sir Charles Saunders led a vast armada of warships and transports up the St. Lawrence for the siege of Quebec, impressive on its rocky 200-foot eminence commanding the river. At the same time, British General Wolfe landed his 9,000 troops (supplemented by American Rangers) on the Isle d'Orleans just below the city. The French tried, but failed, to dislodge the British fleet with fire ships, but Wolfe still had trouble making any headway. In a surprise night maneuver he led a landing party of 4,500 that scaled the heights of Quebec, where a short fight followed on the Plains of Abraham in which both Montcalm, commander of the French forces, and Wolfe were mortally wounded. Five days later, on September 18, Quebec surrendered. The British troops holed up in the city through the fierce winter, and in the spring faced another French army that had marched from Montreal to dislodge them. A bloody fight followed in which the English, outmanned and weakened by a winter of disease and privation seemed destined to lose, but the timely arrival of the British fleet allowed them to evacuate instead. |

|

Quebec: A Celebration in Verse

41. "When proud Quebeck must fall" In: Nathaniel Ames. An astronomical diary … for … 1760, Boston, [1759]. |

|

42. William Cooke, The conquest of Quebec: a poem, London, 1768. |

|

43. Joseph Hazard, The conquest of Quebec. A poem, London, 1769.

Joseph Hazard of Lincoln College and the Reverend Cooke, Fellow of New College and Chaplain to the Marquis of Tweedale, were two runners-up for the "conquest of Quebec" poetry prize offered by the Earl of Litchfield, Chancellor of the University of Oxford. |

Canada Surrendered to the British

In the summer of 1760 British forces advanced on Montreal in a successful multi-pronged attack. The outnumbered garrison had no support from the French navy and no means of escape. Commander Vaudreuil was compelled to surrender and French Canada became a British colony on September 8, 1760. Following the capitulation of Montreal, the Spanish port of Havana fell in 1762 (Spain had joined the conflict on the French side). The long war was finally over in America, but not in Europe until the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1763. By its terms, France ceded Canada and all her territory east of the Mississippi River to Great Britain. |

|

Dying at Quebec

The Death of Wolfe, September 18, 1759

Benjamin West, To the king's most excellent majesty this plate, the death of General Wolfe, is with his gracious permission humbly dedicated, [London, 1776]. |

|

| |

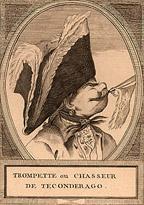

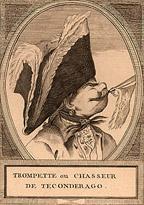

French Caricatures of Colonial Troops

From the evidence of the publisher's imprint it is likely that these engravings were issued in Paris sometime around 1780. But in 1780 there was an alliance between France and the former British colonies, and it seems strange that these rather unflattering caricatures of American “types” were produced during a time of friendship. The facial expressions and the elaborate, European-style helmets and uniforms imply that these figures were being presented as objects of ridicule.

Perhaps an explanation can be found in the fact that the Crépy family of geographers, engravers, publishers, and print sellers had long been active in Paris, especially during the period of the French and Indian War when the British colonists in North America were likely to be depicted in a negative way. It is our suspicion that the plates were engraved during the French and Indian War period (note the figure from Ticonderoga, where the British and colonial forces were defeated by the French in 1758) and re-issued between 1778 and 1781 in recognition of the Franco/American Alliance, with some minor alterations–such as "La Liberté," that appears on the engraving of the soldier from New York. |

|

Trompette ou chasseur de Ticonderago |

Soldat de la province de New York

|

Le Pensilvanien |

Le fantassin Bostonien |

Grenadier de Philadephie |

Le milicien Americain |

|

| |

Exhibition seen in Reading Room from september 2008 through

december 2008.

Exhibition prepared by Susan Danforth, Curator of Maps and Prints. |

|