|

||

Higher education in the Americas was not a theocracy. While most colleges and universities were founded in part to train a colonial clergy, few did only that. Yet the religious orders in the Catholic lands, and the competing denominations in the Protestant ones, played a major role in organizing higher education. The most striking example of this is the Jesuit colleges, famous throughout the Catholic world for their focused and disciplined commitment to education. This case also examines other moments when the sacred underpinnings of early modern higher education emerge, suddenly and clearly, in the sources. |

||

The Jesuit Colleges Founded in the sixteenth century, the Society of Jesus became famous for the well-run colleges it founded throughout the Catholic world, including the American colonies of Spain, Portugal, and France. The Society was an international organization; it maintained good relations with secular governments but ultimately answered to its Superior General, residing in Rome. In 1632, Jesuit colleges received the privilege of granting degrees that were equivalent to university degrees. Eventually, however, the Jesuits’ wealth, power, and loyalty to a foreign power, the papacy, came to seem more a threat than an asset to the Catholic monarchies; in the late eighteenth century, the Jesuits were expelled from the Spanish, Portuguese, and French domains, and their colleges and other property confiscated by the government. 1. “Collegio di S. Giacomo.” In: Alonso de Ovalle, Historica relacione del regno di Cile (Rome, 1646). This woodcut illustrates a Jesuit college in Santiago, Chile. |

||

2. Jesuits, Instruccion, y memoria de lo que se ha de leer cada seis meses en tiempo de renovacion (Madrid, 1662). This exposition of required devotional reading was published for the Jesuits of New Granada and Quito (roughly, modern Colombia and Ecuador). |

||

3. Eusebio de Matos, Ecce Homo. Practicas pregadas no Collegio da Bahia (Lisbon, 1677). In Brazil, which had no university throughout the colonial era, Jesuit colleges played an indispensable role in education and society. The sermons of Eusebio de Matos, the Bahia college’s First Professor (mestre de prima) in theology, were a vehicle for innovative and high-flown baroque speculation on the natures of God and man. |

|

|

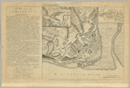

4. Edward Oakley, A plan of Quebec (London, 1759). There were Jesuits in New France as well. This 1759 map shows the Jesuit College of Quebec City, at the heart of the Upper Town, close by the Cathedral. The map, however, was published immediately after British troops occupied Quebec during the Seven Years’ War, which would lead eventually to the Jesuits’ expulsion. |

||

5. John Brown, On religious liberty: a sermon preached at St. Paul's Cathedral (London, 1763). |

||

A lawyer and saint, but not a Jesuit 6. “B.T. ad gradum Licentiati promovetur.” In: Francisco Antonio de Montalvo, Breve teatro de las acciones mas notables de la vida del bienaventurado Toribio arçobispo de Lima (Rome, 1683). This biography of Archbishop of Lima Toribio de Mogrovejo (1538-1606), published as part of the campaign at Rome for his canonization, showed him receiving the licenciatura in civil and canon law at the University of Salamanca. In the Hispanic world, an advanced degree in law was the single most valuable asset for building a career in the interlocking bureaucracies of church and state. For Mogrovejo, this academic honor was the first step in a brilliant career: law professor, Inquisitor General, Archbishop of Lima and, finally, saint. |

||

Harvard versus the enthusiast

|

||

8. Edward Wigglesworth, A Letter to the Reverend Mr. George Whitefield (Boston, 1745). Like the Spanish American universities, Harvard College was equally a sacred and a secular institution. During the Great Awakening of the mid-eighteenth century, the fabulously successful and theatrical itinerant minister George Whitefield antagonized many of the established clergy through whose parishes he traveled. After first inviting him to preach at Harvard, college president Edward Holyoke and a number of the faculty published a denunciation of Whitefield’s excessive “enthusiasm.” Long after its founding, Harvard continued to assert a quasi-official role as theological arbiter for the society around it. |

||

Swearing the Immaculate Conception The University of Mexico City’s manual of oaths specified that all graduates, as well as newly appointed professors, had to swear to uphold the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception of Mary. The doctrine, which held that not only Jesus but Mary as well had been conceived without sin, was still controversial in the Catholic Church, and did not become settled dogma until 1854. But for those who upheld it, it was a matter of partisan passion. Mexico’s was just one of many early modern Catholic universities that attempted to exclude anyone who did not subscribe to it. |

||

More royal or more pontifical? This announcement of graduation theses for the University of Guatemala propounds the question whether a university is primarily a secular or a sacred institution. Invoking the university’s formal title as Royal and Pontifical Guatemalan Academy, the broadside asks: “which title is more appropriate - Royal, for [the university’s] many good services to the Commonwealth, or Pontifical, for its noble deeds for the Church?” |

||

| To next section, Objects of Study. | ||

To read the entire scanned book, go to the John Carter Brown Library's Internet Archive book at this link. |

||

| the Exhibition may be seen in the reading room from April 2014 through october 2014. |