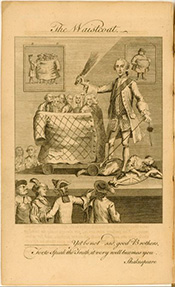

| As an example of how an image can say so much more than appears at first glance, consider the British cartoon in the collection of the John Carter Brown Library. Called “The Waistcoat,” it shows John Stuart, Lord Bute, exerting his influence and tyranny over the government by pulling a cart over the prostrate body of Britannia. Representing the members of the Grafton Administration, seven men stand on the cart enveloped in a giant waistcoat. Lord Bute holds a switch to manage the rather cowed, and/or impassive, members of the government. An image request and subsequent article by Lynne Raymond, a researcher of Edward Bright and inhabitant of his town of Maldon, brought the interesting information to our attention. |

|

|

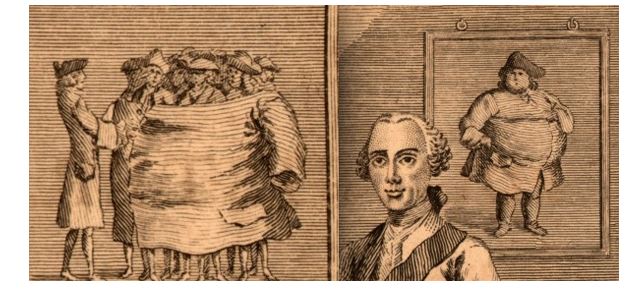

From our remove, this image seems an odd one. But an eighteenth-century English audience would have understood more by looking this picture. They would probably have known of Edward Bright, the grocer of Maldon—a celebrity in mid-century England for his extreme corpulence. His weight in 1749 was 584 pounds (it may have been 616 pounds when he died in 1750); he was 5’9 in height and 6’11” around his belly. He became a grocer and would travel to London on business where, because of his size, he kindled renown in the capital. When he died at 29 years old from "miliary disease," a special coffin had to be made as quickly as possible because his corpse immediately began to decay and a hole had to be cut in the wall of his house to allow it to be removed. As Lynne Raymond writes:

Shortly before his death one of Bright’s waistcoats had been sent to his tailor for enlargement and on 1 December 1750 a wager took place in Maldon’s Bull Inn between Mr Codd and Mr Hants whether five men resident in Maldon could be buttoned inside the waistcoat without breaking a stitch or straining a button. In the event not only the five but seven men with the greatest of ease were included.

To the people of mid-eighteenth century England, the code implicit in this image would have been very obvious, in a way that is quite unapparent to us. The message is further emphasized by the pictures hanging on the wall behind the odd scene—on one side, the picture shows the wager of fitting seven men into Bright’s waistcoat, on the other the Grocer of Maldon himself is portrayed. The English public would have understood the scene demonstrated the impotence of the Grafton administration by showing a band of men too powerless to resist being stuffed into a fat man’s waistcoat. They would have understood that the tyrannical oppressor who was driving the hapless men would even roll over Britannia with his autocratic ambition. On the other hand, we in this century—and without the knowledge that was common in eighteenth-century England—are mostly mystified by a peculiar image.

Lynne Raymond, “EDWARD BRIGHT, ‘THE FAT MAN AT MALDON”, 1721-1750, August, 2014

Essex Naturalist: Being the Journal of the Essex Field Club for 1888, 243-246

|