New England

Slavery and the Slave Trade in Rhode Island

The Brown Family

and the Slave Trade:

The Voyage of the Sally

> Legacies

The Report enjoins its readers to reflect on the “bitter legacies” of slavery that still haunt Americans; it also calls on universities, as special sanctuaries of historical continuity, to lead the effort. Slavery left so many legacies in the United States and around the world that it is impossible to enumerate them all. But in a state as small as Rhode Island, the story can be told with greater clarity.

|

|

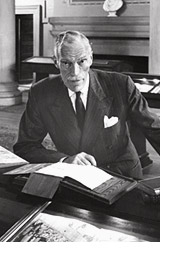

| Nicholas Brown (1769–1841) in 1822 |

Opposition to slavery grew in the nineteenth century, within the Brown family as well as Rhode Island at large. As the Brown and Ives firm turned its attention to new kinds of trade and industry, it gained a reputation for refusing to cooperate with those Rhode Islanders attached to the slave trade. Letters in the Brown Family Papers indicate rising friction with the D’Wolf family of Bristol, still deeply involved with the trade, as Brown family members voiced their growing opposition. One partner of the Brown and Ives firm, George Benson, became the father-in-law to the most famous abolitionist of the nineteenth century, William Lloyd Garrison.

John Carter Brown, the son of Nicholas Brown (1769–1841), grew up in Providence and attended Brown University (Class of 1816). His great love of book collecting led to the creation of an enormous private library, specializing in the European expansion into the Americas. But Brown was not divorced from the great issues of his time. In the 1850s he donated money to support anti-slavery settlers in “Bleeding Kansas,” and after the controversial Harper’s Ferry Raid of 1859, Brown increased his support with the remark, “This is not time for a man with the name of John Brown to hold back.” When he died in 1874, the Providence Journal eulogized him as a devoted opponent of slavery, and as a supporter of recently freed African-Americans after the war.

|

| John Carter Brown (circa 1870) |

O n December 28, 1948, his grandson, the Acting Secretary of the Navy, John Nicholas Brown (1900–1979), wrote a memorandum outlining his view that the Navy ought to embrace “nondiscrimination” on a broad scale and reject the piecemeal approach to desegregation that had been attempted earlier, and was still being considered by segregationists. The full text of this letter, and the context surrounding it, can be found on the website of the Harry S. Truman Presidential Museum and Library.

n December 28, 1948, his grandson, the Acting Secretary of the Navy, John Nicholas Brown (1900–1979), wrote a memorandum outlining his view that the Navy ought to embrace “nondiscrimination” on a broad scale and reject the piecemeal approach to desegregation that had been attempted earlier, and was still being considered by segregationists. The full text of this letter, and the context surrounding it, can be found on the website of the Harry S. Truman Presidential Museum and Library.

__________

Photo (left): John Nicholas Brown is here standing in the John Carter Brown Library's Reading Room (circa 1970).

![]()

![[20] Washington’s Accounts](../Images/Thumbnails/Item20_thumb.jpg) |

[20] Washington’s Accounts larger view

George Washington. [Memorandum Book]. (Mount Vernon, 1799). One of the most treasured artifacts of the Library, this book records the personal expenditures of our first president up until his death in December 1799. As one might expect, it is filled with references to the African-American members of the Mount Vernon community, both free and unfree. Washington was a lifelong slaveowner, but at the end of his life he boldly manumitted his 123 slaves and stipulated in his will that the children he was liberating must also be educated (he was legally unable to free the 153 who belonged to his wife). Here the page is open to a notation for the receipt of $25 for a runaway slave named Cesar. |

![[21] Bible of Revolution](../Images/Thumbnails/Item21_thumb.jpg) |

[21] Bible of Revolution larger view

Guillaume Thomas Francois Raynal. Histoire philosophique et politique des établissemens & du commerce des Européens dans les deux Indes. (Amsterdam, 1770). Scholars now understand with more clarity that the American debate over slavery in the early republic was strongly affected by the Haitian slave rebellion, which erupted in 1791 and led to the first black republic in the world, as well as to the purchase of the Louisiana territory. The Library holds one of the world’s great collections relating to Haiti and its emergence as a free nation. Raynal’s history of the New World was written in collaboration with various authors and banned not long after its appearance for its thinly veiled radicalism. The French historian Jules Michelet called it “the bible of the Revolution.” It has long been alleged, although not proven, that the Haitian Revolution owed its conception to the fact that Toussaint Louverture read the impassioned passage of the book that called for the destruction of slavery. When the Revolution began in 1791, it unleashed a racial conflict with enormous long-term consequences for Haiti and the United States. The war did not end until 1804, leaving many thousands dead, and the new Haitian republic a pariah republic, but nevertheless free and independent. Near the end of the war, Napoleon sold the huge Louisiana Territory to President Thomas Jefferson, transforming the young republic. The sale also set the ground for the debates over slavery’s expansion that would roil the United States in the 19th century. |

![[22] African-American Hero](../Images/Thumbnails/Item22_thumb.jpg) |

[22] African-American Hero larger view

Jean-Louis Dubroca. Vida de J. J. Dessalines, gefe de los negros de Santo Domingo. (Mexico: Mariano de Zúñiga y Ontiveros, 1806). Dubroca was hired by the Bonaparte regime to conduct a propaganda war against Toussaint Louverture, the leader of the slave revolt on Saint Domingue. This work is a similar vilification of Toussaint’s successor, Dessalines. According to Madison Smartt Bell, “As the leader of the only successful slave revolution in recorded history, and as the founder of the only independent black state in the Western Hemisphere ever to be created by former slaves, François Dominique Toussaint Louverture can fairly be called the highest achieving African-American hero of all time. And yet, two hundred years after his death . . . he remains one of the least known and most poorly understood of those heroes.” |

![[23 & 24] Born into Bondage](../Images/Thumbnails/Item23-24_thumb.jpg) |

[23 & 24] Born into Bondage larger view

[Thomas Clarkson]. Résumé du témoignage donné devant un comité de la Chambre de Communes de la Grande-Bretagne et de l’Irlande, touchant la traite des nègres. (Geneva: Chez Magnet et Cherbuliez, 1814). This pamphlet is a translated condensation of Clarkson’s two-volume History of the rise, progress, and accomplishment of the abolition of the African slave trade by the British Parliament (first published in 1808), addressed to the rulers and their representatives at the Congress of Vienna in 1814 to urge them to take steps against the slave trade. The image of slaves as cargo on shipboard was ubiquitous by this time, but the one shown here, detailing a slave woman giving birth, was lately rediscovered by a JCB Fellow. |

![[25] English Emancipation](../Images/Thumbnails/Item25_thumb.jpg) |

[25] English Emancipation larger view

Triumph of Freedom Over Negro Slavery; or, the Ever to be Remembered glorious First of August, 1834. ([London]: Hunt (late Quick), [1834]). Long after the close of the eighteenth century, the international alliance of anti-slavery activists achieved an enormous victory when the British parliament abolished slavery on August 1, 1834. The act was a testament to the efforts of generations of reformers from a wide variety of religious backgrounds, and to the growing power of the printed word to sway opinion. This vivid broadside celebrates not only the great act of 1834, but the life of one of the most tireless English campaigners against slavery, William Wilberforce (1759–1833), who died on the eve of emancipation. Wilberforce, active in both the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, was deeply influential on the American anti-slavery community. English emancipation put enormous pressure on the slavery question in the United States, and is one of many reasons the debate became bitter in the 1830s. John Carter Brown’s vast collection of anti-slavery books and pamphlets is an indication of both his political sentiments and his bibliophilia. |

![[26] Grandson of a Brown Family Slave](../Images/Thumbnails/Item26_thumb.jpg) |

[26] Grandson of a Brown Family Slave larger view

William J. Brown. The Life of William J. Brown, of Providence, R.I. (Providence: Angell & Co., 1883). Not all rare books come from the eighteenth century. This remarkable volume records the life story of William J. Brown, born in Providence November 10, 1814. His grandfather, Cudge Brown, “was born in Africa, and belonged to a firm (named Brown Brothers) consisting of four, named respectively, Joseph, John, Nicholas and Moses Brown;” he became a teamster working on the farms of Moses Brown. His grandson described Moses Brown as “highly esteemed by everyone,” in part because he allowed his slaves to marry. William Brown’s grandparents were married in 1768, five years before the crisis of conscience that led Moses Brown to emancipate all of his slaves. The book offers extraordinary information about African-American life in Rhode Island in the nineteenth century; it also contains valuable stories about Native American customs (Brown’s mother was a Narragansett). |