| While there is some truth to the notion that the majority of books published in Spanish America were of a religious nature, the range and variety of publications encompasses a multitude of genres. | ||

Indigenous Languages 53. Andrés Febrés, Arte de la lengua general del reyno de Chile (En Lima: En la calle de la Encarnacion, 1765).The necessity of producing indigenous language texts drove the introduction of the printing press in both New Spain and Peru. While it was certainly possible to send manuscripts to Spain for printing, this would entail delay, and worse, a great potential for errors if the author were not there to correct the proofs. A large percentage of the early books produced in America were in native languages, and, after a dip in the seventeenth century, their printing became more frequent again in the eighteenth century. This text, in Mapuche, is one of nearly 8,000 books the JCB has contributed to the Internet Archive. Among these, it is the most popular, having been downloaded over 3,000 times. |

||

Sermons 54. Juan Antonio Dighero, El pantheon real, funebre aparato a las exequias, que en la ciudad de Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala se hicieron por el alma, y a la piadosa memoria de nuestra catholica reina, y señora, doña Maria Amalia de Saxonia (Impresso en Guatemala: En la Imprenta de Sebastian de Arebalo, 1763).Beginning in the seventeenth century, sermons of various types became an increasingly common genre of printed works. Funeral sermons in particular saw frequent publication. Occasionally, as in this eulogy for María Amalia of Saxony, wife of Charles III, engravings of the catafalque mounted in the cathedral would accompany them. |

||

Laws 55. Peru (Viceroyalty), Don Melchor de Nauarra y Rocafull, cauallero del orden de Alcantara, duque de la Palata, principe de Massa, de los Consejos de Estado, y Guerrra de su Magestad, virrey, gouernador, y capitan general de estos reynos del Peru, Tierrafirme, y Chile, &c. ([Lima: s.n, 1682]).While the press served the clerical establishment with texts to assist with the evangelization of the native population, the secular establishment had need for printed laws, bandos, reales cedulas, and the like. |

||

Legal Briefs 56. Jesuits, Informe, que haze la provincia de la Compañia de Jesus, de esta Nueba España, por lo que toca à la parte de sus missiones (En la Puebla: Por la Viuda de Miguel de Ortega Bonilla, en el Portal de las Flores, 1729).In The Colonial Printer, Lawrence Wroth wrote of British North America: "In examining the records of the colonial communities, one is appalled by the amount of legal and official business that was transacted in this new country, but whoever else may have been the sufferer by this frequent lawing, it is certain that it was not the printer." Much the same can be said of Spanish America and the vast number of legal briefs that were printed to accompany litigation. |

||

Literature and Poetry 57. Bernardo de Balbuena, Grandeza mexicana (En Mexico: En la emprenta de Diego Lopez Daualos, 1604).Relatively few works of a purely literary nature were printed in Spanish America. Given their great popularity and relatively low cost to print, it seems odd that no comedias were reprinted in the Americas. On the other hand, poetry flourished. Beyond texts such as the Grandeza Mexicana, a long poem on the riches and diversity of Mexico, a good number of texts in other genres were prefaced by laudatory odes. Here the text is opened to the verse on booksellers, engravers, and printers. |

||

Music 58. Juana Inés de la Cruz, Villancicos, que se cantaron en los maytines de el glorioso principe de la Iglesia el señor San Pedro (En Mexico: Por los Herederos de la Viuda de Bernardo Calderon, 1692).Similarly, while music had been printed in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, it was not until the later eighteenth century that it again appeared. Texts meant to be accompanied by music, such as Sor Juana's Villancicos, were very popular, however. |

||

Practical Guides 59. Pedro Murillo Velarde, Practica de testamentos, en que se resuelven los casos mas frequentes (Mexico: En la imprenta del nuevo rezado de los herederos de doña María de Rivera, 1755).Pedro Murillo's Practica de testamentos was first published in Manila in 1745, and on multiple occasions thereafter, into the nineteenth century. It provides a clear and concise distillation of relevant laws related to the composition and content of last wills. While primarily intended for notaries, it also notes occasions and methods for writing testaments when notaries were not available. Interestingly, this 1755 edition, published by the heirs of María Candelária de Rivera, was funded by Antonio Adan, who did her testament the previous year. |

||

Vade Mecum 60. Francisco Juan Garreguilla, Libro de plata reduzida que trata de leyes baias desde 20 marcos, hasta 120 (Impresso en Lima: Por Francisco del Canto, 1607).Handbooks and aids to commerce were essential tools for merchants and miners. The earliest published in the Americas date to the sixteenth century. This guide to the value of silver of various degrees of purity saw heavy use in the field. |

||

Illustrations and Engravings 61. José María Montes de Oca, Vida de San Felipe de Jesus: protomartir de Japon y patron de su patria Mexico (En Mex.co: Calle de Bautisterio de S. Catalina M. n. 3, 1801).Even the earliest imprints in Spanish America included some type of illustrations, usually woodblocks. The first copperplate engravings to appear in print were in Mexico in 1609. While woodblocks could be printed along with the type, copperplates required a separate press. By the end of the seventeenth century, engravers had established their own shops, as did Montes de Oca, a prolific engraver who studied at the Academia de San Carlos. He eventually moved to Queretaro where he opened a school of art. |

||

Periodicals 62. Gazeta de Mexico (Mexico: Por D. Felipe de Zuñiga y Ontiveros, Calle del Espirítu Santo, 1784).The precursors of the periodical press were the relaciones de sucessos, news-sheets that generally mentioned singular events. The first periodical in Spanish America was the Gazeta de México, which was issued during the first six months of 1722. While a second run followed some years later, it was not until the later eighteenth century that continuous publication was established. |

||

Scientific and Literary Press 63. Mercurio peruano de historia, literatura, y noticias públicas que da à luz la Sociedad Academica de Amantes de Lima (Impreso en Lima: En la imprenta real de los Niños Huérfanos, 1791).Literary and scientific periodicals began to appear in the later eighteenth century. The Gazeta de literatura in Mexico, and the Mercurio Peruano in Lima introduced their readers to contemporary European developments in the sciences, often closely attuned to their local New World contexts. |

||

|

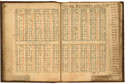

Almanacs 64. Almanak y kalendario general diario de quartos de luna, segun el meridiano de Buenos-Ayres. Para el año del señor de 1797 (En Buenos-Ayres: En la Real Imprenta de Niños Expósitos, [1796]). |

||

| 65. El conocimiento de los tiempos, efemeride del año de 1790 ([Lima]: En la Imprenta Real, calle de Concha, [1789]). Almanacs were published on an annual basis as early as the seventeenth century. Virtually all of these are known only from documentary evidence since so few survive. Even later almanacs are rather scarce, given their ephemeral nature. |

||

City Guides 66. Mariano José de Zúñiga y Ontiveros, Calendario manual y guia de forasteros en Mexico, para el año de 1796 ([Mexico]: En la Oficina del Autor, [1795]).A similar genre, often issued together with an almanac was the guia de forasteros, or guide to the civil and ecclesiastical hierarchy. In Mexico, Zúñiga y Ontiveros obtained a monopoly on these profitable texts. The 12mo format, tall and narrow, clearly marks it as a book intended to be carried with its owner. |

||

Reading Primers 67. Catholic Church, Cartilla mayor, en lengua castellana, latina, y mexicana (En Mexico: en la Imprenta de la Uiuda de Bernardo Calderon en la calle de San Augustin, 1691).Primers of reading and religious fundamentals, known as cartillas were published in the tens of thousands, however, extraordinarily few survive. They appeared in one, two, and occasionally three languages and were frequently read to death. Printers jealously guarded their monopoly privileges over these pamphlets. Despite a low fixed price of 1/2 real each, and an annual alms payment for the privilege, these were very lucrative titles. |

||

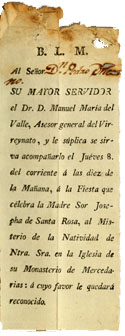

Ephemera 68. José de Borda y Echeverría, B.L.M. Su mayor servidor D. Joseph de Borda y Echeverria ([Lima: s.n, 173-]). |

||

| 69. Manuel María del Valle, B.L.M. Al Señor [...] ([Lima?: s.n, between 1792 and 1796?]). Ephemeral items like these invitations were a printer's bread and butter. Easily and quickly set up and printed, they ensured a steady cash flow between other larger jobs. |

||

| to the beginning | ||

| Exhibition prepared by Kenneth C. Ward. on view in the reading room from october 2014 to February 2015. |

||