| |

aFRICAN CULTURE

FROM CURIOSITY TO AMBUSH

Sloane's natural history included the study of plants, animals, minerals, climate, soil, topography, commerce and human populations. He conceived of their description as both a pious survey of the variety of the divine creation and a strategic reconnaissance of "one of the largest and most Considerable of Her Majesty's Plantations." This section explores some of the non-botanical objects Sloane collected (such as musical instruments) and Africans' contributions to collections like Sloane's. While Sloane actively participated in and benefited from the order of slavery in Jamaica, he nevertheless took pains to describe and preserve enslaved African cultural artifacts as few others did at the time. This section also explores African uses of works of nature and artifice that lay outside European knowledge systems and sometimes directly conflicted with them. Although practices like Obeah originated as material and spiritual resources for healing and attack within the Afro-Jamaican community, they became part of militant resistance to colonial authority. As the British came to realize, objects they ignored or regarded as mere curiosities might in African hands turn into weapons that could destroy the order of slavery.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

20. Ancient Jamaicans

“Harvesting guava and papaya” In: Mr. N***, Voyage aux côtes de Guinée et en Amérique (Amsterdam, 1719).

This anonymous depiction of indigenous Americans harvesting guava and papaya in the Caribbean draws our attention to the absence of Jamaican Tainos in Sloane’s time, decimated by disease and violent confrontation with the Spanish. By Sloane’s day, such harvests were performed by enslaved West Africans, whom he sought out as the living repositories of indigenous and Spanish knowledge of the island. Sloane noted the presence of recent Amerindian migrants in Jamaica and their hunting prowess but remained vague on their provenance. He was more concerned with the Taino. He brought back fragments of clay urns and indigenous human remains discovered in a cave near Red Hills. An English Protestant, he framed these as evidence of Spanish atrocities, keeping alive the ‘Black Legend’ of Spanish cruelty. Interestingly, he classified these urns in his Antiquities catalog, along with ancient British, Greek, Roman and Egyptian artifacts. |

|

|

21. African Animals and Environmental Transformation

Louis Freret, Arrivée des Européens en Afrique (Paris, 1795).

Freret’s engraving portrays the encounter between Africans and Europeans on the West African coast as one mediated by the animals (parrots) offered to the new arrivals, possibly as gifts or an invitation to trade and exchange. The image appears ambiguous: it might be seen as heralding African natural mastery (hence the parrots, tusks, fish, monkeys, feathers and elephants at their command) or a fantasy of resistance-free European access to such bounty. By 1795, slave trade ships had for decades brought domestic animals to the Caribbean: guinea fowl and sheep (as well as guinea grasses) were an important food source. Freret’s image by contrast focuses on exotic specimens. Sloane made observations of both rare animals and livestock in Jamaica, noting African provenance where possible, making his Natural history an important document of Caribbean environmental transformation. |

|

|

22. Afro-Caribbean Harvests

Audinet after Agostino Brunias, “A negro festival” In: Bryan Edwards, The history, civil and commercial, of the British colonies in the West Indies (London, 1793).

By foregrounding the presentation of exotic fruits at the feet of English colonists in St. Vincent (the site of an important botanical garden) by a doubled-over African woman, this image seems to suggest colonial projections of painless access to local agricultural abundance and female obeisance therein. But in associating this woman with the harvest of local fruits, it also calls to mind the provision grounds run by Africans to feed themselves in lieu of proper provisioning by Caribbean planters. Sloane likely visited such grounds while in Jamaica and noted the cultivation of potatoes, yams and plantains by the enslaved. Such ‘gardens’ were spaces of enslaved agricultural autonomy that sustained African botanical traditions. |

|

|

23. Market Exchanges

“Vue du grand marché” In: Pierre Jacques Benoit, Voyage à Surinam (Brussels, 1839).

This image from the Belgian artist Benoit’s romanticized account of his Surinam travels recalls similar depictions of markets in St. Vincent by Agostino Brunias and Antigua by William Beastall. These markets were fundamental to the internal economy of Caribbean societies and already existed in Jamaica by Sloane’s time. It is likely that Sloane – who documented the provision grounds of enslaved cultivators – would have visited them, drawn by his curiosity about local flora and fauna. We know that his friend Henry Barham did so; representations, including Benoit’s, regularly feature white visitors mixing with enslaved and free Africans. Itinerant African traders known as higglers brought livestock, dairy and agricultural produce, rare animals and objects for commercial sale or exchange in kind. Sloane may have purchased specimens from such traders. |

|

|

24. Botany Among the Enslaved

Henry Barham, Hortus Americanus (Kingston, Jamaica, 1794).

Barham was a physician and planter based in Jamaica in the early eighteenth century. He was Sloane’s closest correspondent on the island, and a dutiful annotator of the Natural history of Jamaica (Sloane incorporated several of his corrections and additions in volume two). Barham’s own natural history was published posthumously decades after his death. His manuscripts reveal how his residency in Jamaica gave him a more detailed appreciation of African knowledge of the island’s flora and fauna than Sloane’s. For example, Barham acknowledged enslaved expertise in medicine, including the practice the English referred to as Obeah, and used African names where Sloane adopted only English and Latin terms. He supplied Sloane with numerous specimens and some singular curiosities, including bullets and clothing that he said came from Jamaica’s Maroons. |

|

|

25. Snake Charmers

The skinning of the Aboma snake” In: John Gabriel Stedman, Narrative of a five years’ expedition to Surinam (London, 1806).

This image, from the Scottish-Dutch soldier Stedman’s narrative of his Surinam journey, depicts him directing three African men to kill and flay a large snake named Aboma. It is not clear if these men are slaves or if Stedman is paying them for their services. Perhaps unwittingly, the image emphasizes European passivity and African dexterity in the face of American fauna. Collectors like Sloane would often have turned to African or Indian hunters as sources of elusive or dangerous specimens. Sloane recounted stories of Indian snake-charmers in Jamaica and, evidently eager to emulate such mastery, attempted to ship a live six-foot yellow snake back to London. He fed it carefully, but it escaped its makeshift container and was shot dead by the Duchess of Albemarle’s startled attendants. |

|

|

26. Traduttore/Traditore:

“The celebrated Graman Quacy” In: John Gabriel Stedman, Narrative of a five years’ expedition to Surinam (London, 1796).

Even when compensated, virtually no Africans engaged by colonizers to collect were individually credited in published works of natural history. The outstanding exception is “the Celebrated Graman Quacy,”—otherwise known as Kwasímukámba—who secured his freedom by helping Dutch soldiers hunt down runaway slaves in Surinam. Quacy had the Quassia Amara named after him by Linnaeus, was sometimes referred to as “Professor of Herbology in Surinam” and was presented to Prince Willem V of Orange in the Hague in 1776. This engraving by William Blake portrays him dressed as a gentleman, with a Dutch fort in the background (notice how Quacy’s clothes echo the colors of the Dutch flag). Stedman, who encountered him in Surinam, described him as “very proud” and “very saucy” and “not unlike one of the Dutch generals.” |

|

|

27. Acts of Assembly

Jamaica. Laws, etc. Acts of Assembly, passed in the island of Jamaica. from the year 1681 to the year 1769 inclusive. An appendix containing laws respecting slaves (Kingston, 1787).

When Sloane visited Jamaica, legislation for the discipline and punishment of enslaved Africans was becoming increasingly important, given the expansion of the black population. After the Restoration, a 1661 proclamation had declared white settlers “free Denizens of England,” while the first comprehensive act concerning slavery in 1664 (based on legislation in Barbados in 1661) described “Negroes” as “Heathenishe brutish and uncertaine and dangerous.” This justified laws for their coercion, punishment and restriction of movement as “protection” from “arbitrary cruell and outragious [sic]” treatment. In response to further rebellions among the enslaved and continual agitation by the Maroons, these laws were strengthened in 1696 (to include anti-poisoning measures, for example). This legislation reveals how difficult it was for colonial authorities to police the movement and co-operation of Africans in Jamaica. Sloane described the means of punishing enslaved rebels in his Natural history but said almost nothing about the rebellions themselves or Maroon resistance. |

|

|

28. Jamaican Curiosities

Hans Sloane, Natural history of Jamaica, vol. 1. (London, 1707).

The composition of this engraving reflects Sloane’s multiple preoccupations as a naturalist and collector: the desire to document local customs, link natural materials and artificial productions, and compare the craftsmanship of the world’s different peoples. It features (front to back) South Asian, Jamaican and West African stringed instruments. It punningly juxtaposes a Jamaican luteus plant (“5”) with which Africans cleaned their teeth: Sloane described what he called the Jamaican “Strum Strum” as being an “imitation of lutes.” Sloane brought this instrument back from Jamaica in 1689 and had it drawn by Kickius. He described it as consisting of “small gourds fitted with necks, strung with horse hairs, or the peeled stalks of climbing plants or withs.” The means of its acquisition is unknown: Sloane may have paid for it, exchanged for it, or taken it through coercive means. |

|

|

29. Music in Transit

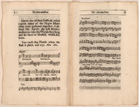

Hans Sloane, Natural history of Jamaica, vol. 1. (London, 1707).

Sloane claimed to have witnessed performances of African dance and music in Jamaica. This remarkable transcription, made by a man named Baptiste, is one of the earliest known recorded pieces of African music in the Americas. It notes three West African variants identified as “Angola,” “Papa,” and “Koromanti.” The ethnomusicologist Richard Rath has argued that these embody an early stage in the development of African-American music, part pidgin, part Creole, including both West African elements and West Indian fusions. The words suggest a variety of possible themes: sexuality, the spirits of dead ancestors, children at play and physical comfort. While other Caribbean travelers described African music, Sloane’s collection of instruments and transcriptions was without precedent and perhaps paradoxical. His written descriptions emphasized the base passions of such performances, but he nevertheless took pains to preserve their artifacts. |

|

|

30. Instruments of Rebellion

“Negers Speelende op kalabassen” In: Johannes Nieuhof, Gederkweerdige Brasiliaense zee en lant-reize. (Amsterdam, 1682).

Nieuhof was a traveler who worked for the Dutch East India Company and held official positions in India and Ceylon. He was best known for his writing on China, but also visited Brazil. Unlike Sloane’s images of African instruments and music in the style of isolated specimens, this image portrays Africans in Brazil dancing and playing a calabash and tambourine. Sloane noted in 1707 that the British had banned the use of trumpets and drums in Jamaican festivals, in recognition of their military use in West Africa and their ability to foster solidarity and potentially rebellion among the enslaved. Their prohibition doubtless heightened their value as curiosities. Sloane’s ‘Akan Drum’ – one of the drums used to exercise Africans on the Middle Passage, sent to him from Virginia by a man named Clerk after 1730 – is held by the British Museum. |

|

|

31. African Healing

“Mama-Snekie, ou Water-Mama, faisant sa conjurations” In: Pierre Jacques Benoit, Voyage à Surinam. (Brussels, 1839).

This image features Benoit’s encounter with a female African practitioner in Surinam of what he called “sorcery”: “Mama Snékie” or the “Mere des Serpents,” also known as “Water Mama”(Benoit’s guide is also in the frame). Benoit regarded African healers as charlatans, but was deeply curious about them and their tools. “Tata, Tata, helpie wie,” he recorded her words, which he translated as “God, help me.” Female African healers were regarded as powerful and sometimes dangerous figures in African-American societies. While rejecting their belief systems, settlers often turned to them for medical assistance, acknowledging their greater experience with local plants and animals. Sloane ignored such ‘magical’ practices in Jamaica and wrote dismissively of African healing techniques. However, he did record fragments of the conversations he had with Africans about disease and medicinal plants while in Jamaica. |

|

|

32. Fetishism

Hermann Moll, “A new and exact map of Guinea” In: Willem Bosman, A new and accurate description of the coast of Guinea. (London, 1705).

The Dutch traveler Bosman’s account of European interactions with Akan gold traders on the West African coast has been identified as a crucial moment in which Europeans first began formulating their concept of the ‘fetish.’ The origins of later theories of fetishism, such as Marx’s theory of commodity fetishism, have been traced to these accounts that describe African ascriptions of active spiritual powers to artificially made objects. Commentators in the eighteenth-century West Indies likewise identified the practice of “Obeah” as a transplanted form of West African sorcery or witchcraft that deployed carefully constructed obis as charms for protection and attack. Unlike other travelers, Sloane, perhaps surprisingly, says almost nothing about such practices or objects in Jamaica. He was likely ignorant as to the full extent of their usage and significance but may also have deliberately ignored them. |

|

|

33. Obeah

Edward Long, The history of Jamaica. (London, 1774).

Long was a Jamaica-based English planter whose published survey of the island included a racialized defense of slavery as a force for civilizing Africans, while also criticizing planter corruption. He described Jamaica’s civil and natural history and documented many individual plant and animal species, emulating Sloane and citing him approvingly. In the aftermath of the significant slave uprising known as Tacky’s Rebellion in 1760, he wrote warningly of the role of “Obeiah-men” as “pretended sorcerers” who emboldened African resistance through supernatural belief in physical invulnerability. The notion that such “priests” were charlatans credited only by credulous Africans may help explain Sloane’s neglect of this phenomenon. Since eighteenth-century scientific writers increasingly contrasted enlightenment botany to ancient druidical magic, Obeah doubtless struck Europeans as a highly atavistic if also threatening form of magical practice. |

|

|

34. Contested Powers

Stephen Fuller, Notes on the two reports from the Committee of the Honourable House of Assembly of Jamaica. (London, 1789).

The anti-abolitionist Stephen Fuller, Jamaica’s agent in Westminster, was Sloane’s grandson-in-law (Elizabeth Rose, Sloane’s step-daughter, had married into the Fuller family of Sussex in 1703). His reports warned about the dangers of Obeah. While European collectors like Sloane gathered plants and animals for both cosmological and practical purposes (taxonomy and pharmacopoeia), Africans mobilized similar specimens and objects for their own purposes: healing, poisoning, religious worship and trance-based spiritual communication with ancestors. They used grave dirt, animal parts, feathers, rum, eggshells, blood and various plants in their preparations. The British attempted to ban their use by law after Tacky’s Rebellion and Fuller described the execution of Obeah-men bearing feathers and other regalia. He also cited Sloane and Barham as sources on the dangers of African poisoning. |

|

|

35. Three-Fingered Jack

Fairburn's edition of the wonderful life and adventures of three-fingered Jack, the terror of Jamaica! (London, [1820]).

This novel offered one version of the celebrated exploits of a formidable fugitive Afro-Jamaican named Jack Mansong (“the terror of Jamaica”) who defied recapture until he was finally killed by the Maroon allies of the British in 1781. This contest is represented in the novel’s early frontispieces, which also depict the obi Jack reputedly carried around his neck. The Kingston surgeon, William Moseley, claimed that Jack’s obi consisted of a goat’s horn containing grave dirt, ashes, the blood of a black cat and human fat. It was said that Jack received his obi from an old cave-dweller in the Blue Mountains. His story was made into a stage play and performed in London in 1800 and he became a romantic hero as debate raged over the abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire. |

|

|

36. Trees, Memory and Identity

“Old Cudjoe making peace” In: Robert Charles Dallas, The history of the Maroons. (London, 1803).

“Old Cudjoe making peace” is a British commemoration of the peace treaty they signed with Jamaica’s Maroons, led by Captain Cudjoe, in 1739. The background suggests the crucial role trees played in Jamaican life. Sloane’s drawings of trees (done by Garrett Moore) isolated them from their environmental and human contexts, rendering them as delocalized specimens and potential resources for export as timber. But trees performed powerful functions in Afro-Jamaican society. Africans spoke of duppies (spirits) haunting cotton and almond trees; Maroons placed defensive charms in specific trees; Matthew ‘Monk’ Lewis recorded how cotton, cocoa and mahogany trees marked important places and moments in the ‘Anansy’ stories his slaves recounted; and Cynric Williams told of one African who claimed compensation from a master who had cut off the branch of a calabash tree that his grandfather had planted. |

|

|

37. Ambush and Camouflage

Philip Thicknesse, Memoirs and anecdotes of Philip Thicknesse. (London, 1788).

Thicknesse was a British soldier and author who described British “astonishment” at the camouflage and ambush tactics of Maroons in the 1730s. The British recognized the Maroons by treaty in 1739 in return for a controversial agreement to return runaway slaves. Maroons often practiced what they called “Science” (similar to Obeah) against their enemies. The 1739 treaty acknowledged Maroons’ unequalled mastery of Jamaica’s mountainous landscape. Sloane avoided Maroon country on his travels and his use of the term “ambush” may signal his awareness of their camouflage prowess. Jamaican Jonkonnu parades to this day feature a camouflage-style figure called “Pitchy Patchy.” The origins and significance of this figure are ambiguous. Although compared by the British to their folk character called “Jack in the Green,” it probably derives from West African masquerade traditions and may also be a form of anti-Maroon satire performed by slaves and their descendants. |

|