Laboratory Primate Newsletter

Laboratory Primate Newsletter

Laboratory Primate Newsletter

Laboratory Primate Newsletter VOLUME 40 NUMBER 1 JANUARY 2001

Behavioral Enrichment for Marmosets by a Novel Food Dispenser, by B. Voelkl, E. Huber, & E. Dungl......1

Puzzle Ball Foraging Device for Laboratory Monkeys, by C. M. Crockett, R. U. Bellanca, K. S. Heffernan, D. A. Ronan, & W. F. Bonn......4

Who’s Enriching Whom? The Mutual Benefits of Involving Community Seniors in a Research Facility’s Enrichment Program, by N. Megna & J. Ganas......8

Early vs. Natural Weaning in Captive Baboons: The Effect on Timing of Postpartum Estrus and Next Conception, by J. Wallis & B. Valentine......10

Discussion: Enrichment for Lemurs......14

News, Information, and Announcements

Meeting Announcements......3

Workshop Announcements......7

...Teaching Research Ethics; Orangutan Reintroduction and Protection

Call for Papers: AAZV......13

News Briefs......15

...Ape Caper Foiled; Death of a Chimpanzee at Coulston; Anna Mae Noell, Owned “Chimp Farm”; LEMSIP Chimps Retire to Texas; Three New Lemur Species; Clinton Signs Great Ape Conservation Bill Into Law

Letters: Howling Howlers......16

Awards Granted......17

...PCWS Conservation Grant; NCRR Primate Grants

Award Nominations: Fyssen Foundation......17

Research and Educational Opportunities......20

...Continuing Education for Lab Animal Technicians; Primate Behavior and Ecology Program - Panama; Field Course in Animal Behavior - Georgia and Africa; Research in the Biology of Aging; Summer Apprenticeship: Chimpanzees and ASL

Information Requested or Available......22

...International Veterinary Information Service; New Video Available; Introducing PIN WEB LINKS; E-mail News Groups: ZooNews Digest and Zoo Biology; More Interesting Web Sites

Grants Available......23

...ACLAM Foundation Request For Proposals; National Research Service Awards for Senior Fellows; Behavioral Science Award For Rapid Transition

Resources Wanted and Available......24

...Species Information Service Launched; Material Exchanges; Primate-Enrichment.Net; Free Software for Studying Behavior

Announcements from Publications......36

...International Journal of Comparative Psychology; Institute for Laboratory Animal Research; APE Boletín on the Web

Departments

Address Change......7

Primates de las Américas...La Página......18

Positions Available......19

...Clinical Lab Animal Veterinarian/Assistant Director; Primatology/Psychology - Bucknell University; Animal Behavior/Biology - Bucknell University; Gorilla Keeper - Georgia; Biological Anthropologist - Florida; Life Sciences Job Resource

Recent Books and Articles......25

* * *

Behavioral Enrichment for Marmosets by a Novel Food Dispenser

Bernhard Voelkl, Edith Huber, and Eveline Dungl

Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognition Research

Introduction

Environmental enrichment for captive primates is unquestionably an important part of managing research facilities and zoos. This is recognized by the U.S. government, which emphasized that "...in addition to providing the required standards of veterinary care and husbandry, regulated research facilities must...promote the psychological well-being of primates used in laboratories" (APHIS, 1995). To meet these demands, captive environments should encourage the expression of social and ecological skills. These should include foraging - searching for food - and food processing, both manual and oral.

In the wild, marmosets spend 50 to 60% of the day foraging (Rylands & deFaria, 1993), while in captivity feeding takes just a few minutes if the food is offered on an open plate. Animals in the wild have to spend more time feeding than in captivity, partly because some food sources have to be processed first, but mainly because they have to search for food, while captives often get all their food offered at the same time and place every day. To increase the animals' foraging behavior, it is advisable to distribute food over the whole living area and/or over the day (Novak & Drewson, 1989; Snowdon & Savage, 1989; Buchanan-Smith, 1997). One way of distributing food over the day is to use the food dispenser presented here. This dispenser has been constructed for feeding marmosets live mealworms. Besides exudates and fruit, insects are an important constituent of the diet of marmosets (Rylands & deFaria, 1993) and tamarins (Garber, 1993). By providing insects, we not only enrich the animals' lives but also supply them with important proteins which are not available from plants.

The Food Dispenser

The dispenser consists of a cylindrical storage tank (14 cm in diameter) with a funnel-shaped bottom (inclination about 10°) and a tube (10 mm in diameter) connecting the funnel with the interior of the cage. The tank can be detached from the dispenser (Figure 1) for cleaning. The tank is filled with about 30 g of mealworms, which crawl over the opening of the funnel, lose their grip, and slide through the tube into the cage, becoming prey for the monkeys. This dispenser provides the monkeys with a relatively small number of mealworms (about 300), more or less evenly distributed over a few hours, through a simple mechanism (Figure 2).

Figure 1: The food dispenser consists of a cylindrical storage tank (A) set in a tray (B), and a tube (C) connecting the funnel of the tank with the interior of the cage (E). The inclination of the tube (a) is about 60°. The dispenser is fixed at the cage with two hooks (D).

Figure 2: Mean number of mealworms eaten per minute using the dispenser (dotted line, flattened, 10 trials), or offering the mealworms in a bowl (solid line, flattened, 3 trials). The graphs are flattened by xi'= 1/3xi+2/9xi-1+1/1xi-2+2/9xi+1+1/9xi+2.

Subjects

The subjects were a group of 11 common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) kept at the Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognition Research, Altenberg, Austria. All animals were born in captivity. The group lived in an indoor cage (2 x 3.5 x 3 m) equipped with branches, ropes, and living plants. The animals were fed fruits, vegetables, monkey pellets, insects, and protein supplements. They were kept at a daytime temperature of 26-30°C, and a night temperature of 21-23°C. Humidity was about 70-80%. In summer daylight was the main source of lighting, while in winter daylight fluorescent tubes were used to maintain a 12:12 hour light:dark cycle.

Method

Some enrichment devices encourage subjects to modify their behavior or to learn new skills (e.g. Marsy & Boussekey, 1992; Reinhardt, 1994; Citrynell, 1998). In the case of the mealworm dispenser we did not expect qualitatively new behavior: as soon as the mealworm falls to the floor of the cage it just has to be picked up - not a very sophisticated task at all. Rather we expected a quantitative shift in locomotor activity: we hypothesized that the subjects would inspect the dispenser frequently, to see if another mealworm were available. Therefore we decided to use a relative measurement for locomotor activity to assess whether the food dispenser has an effect on the monkeys' behavior.

An area of 40 x 40 cm was marked out around the mealworm dispenser, which was attached to the front of the cage. Over 10 days, we measured how often the monkeys entered that area during one hour when no mealworms were available (Control Phase) and when they were available (Test Phase). An increase in the monkeys' activity in front of the food dispenser during the Test Phase would not necessarily mean that their locomotor activity had increased. Such an increase could be caused purely by a local activity shift. It could even be that the animals were moving less, because they were waiting for the mealworms near the dispenser. To check for such an effect, another area of the same size was marked out at the rear of the cage. Only when the activity in the area around the dispenser rose while the activity in the rear area stayed constant, would we suggest that the locomotor activity of the subjects rose.

Results

Activity increased significantly in the area of the dispenser when mealworms were available (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, z = -2.803, p = 0.005). However, in the rear area of the cage, activity did not decrease (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, z = -1.376, p = 0.169). That means that this feeding device not only leads to a shift of the activity to the area of the feeding device but also increases the monkeys' total activity (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Number of times subjects entered the area around the dispenser (Dispenser) or the control area at the rear part of the cage (Rear), during 30 minutes when dispenser was filled with mealworms (Test) and during 30 minutes when no mealworms were available (Control). The bold line shows the median; the box the second and third interquartil; and the lines the range.

Due to the erratic movements of the mealworms, it is unpredictable when the next one will be provided - from just a few seconds up to several minutes. As it can take quite long until the next worm is delivered, and as the total period of time during which mealworms are dispensed amounts to several hours, the monkeys did not sit in front of the dispenser throughout the entire feeding period. At the beginning of the Test Phase the dominant female kept the other group members away from the dispenser, but she left after 10 to 20 minutes, leaving the other animals access to the dispenser. Thus the dispenser was not monopolized by a dominant individual for more than 10% of the total time.

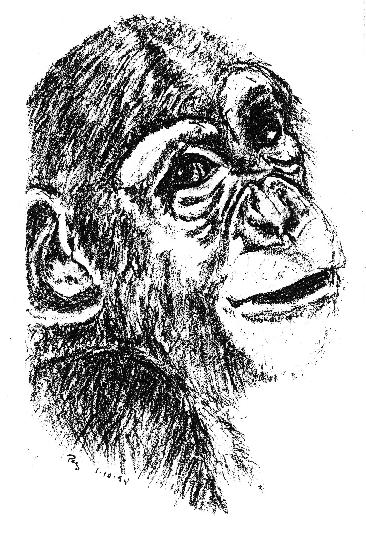

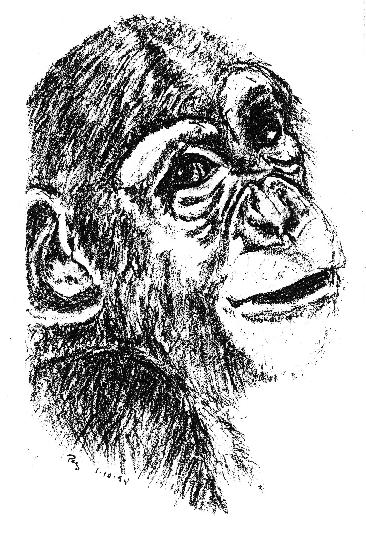

Figure 4: A marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) in front of the dispenser, waiting for a mealworm.

Conclusion and Animal Welfare Implications

The dispenser offers several advantages over conventional feeding methods: (1) The food is distributed over a longer period of time. A food dispenser filled with 30 g of mealworms lasts about three hours, whereas the same amount of mealworms is consumed within four to six minutes when they are freely accessible. That means that the time spent foraging (= looking for food) increases. (2) The food is not permanently available but instead is available randomly. This unpredictability may raise the vigilance of the animals. (3) Maintenance is easy and does not require much additional time. The dispenser itself is attached to the outside mesh of the cage and can be refilled without opening the cage. (4) Even small amounts of food delivered by the dispenser have a strong effect on the behavior of the animals. This is important, because all enrichment activities related to food have to be incorporated into the feeding schedule; this is much easier when the amount of food needed for enrichment is low. (5) It is inexpensive. This is also important, because high additional costs are often used as an argument against behavioral enrichment. This rather simple apparatus can help to enrich the monkeys' foraging experience and thus reduce boredom and monotony. It can be used not only for marmosets and tamarins, but also for other insect-eating primates.

References

APHIS 1995 Factsheet: Regulatory enforcement and animal care. United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

Buchanan-Smith, H. M. (1997). Environmental control: An important feature of good captive callitrichid environments. In C. Pryce, L. Scott, & C. Schnell (Eds.), Marmosets and tamarins in biological and biomedical research (pp. 47-53). Salisbury, UK: DSSD Imagery.

Citrynell, P. (1998). Cognitive enrichment: Problem solving abilities of captive white-bellied spider monkeys. Primate Eye, 66, 16-17.

Garber, P. A. (1993). Feeding ecology in the genus Saguinus. In A. B. Rylands (Ed.), Marmosets and tamarins: Systematics, behaviour, and ecology (pp. 273-295). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Maier, W., Alonso, C., & Langguth, A. (1982). Field observations on Callithrix jacchus jacchus L. Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde, 47, 334-346.

Marsy, P. & Boussekey, M. (1992). Environmental enrichment of the golden-bellied mangabey (Cercopithecus galeritus chrysogaster) groups in a zoological garden: Effects of puzzle feeder vs. food dispersion in litter. Proceedings of the XIVth Congress of the International Primatological Society, 307.

Novak, M. A. & Drewson, K. H. (1989). Enriching the lives of captive primates: Issues and problems. In E. F. Segal (Ed.), Housing, care, and psychological well-being of captive and laboratory primates (pp. 161-182). New Jersey: Noyes Publications.

Reinhardt, V. (1994). Caged rhesus macaques voluntarily work for ordinary food. Primates, 35, 95-98

Rylands, A. B. & de Faria, D. S. (1993). Habitats, feeding ecology, and home range size in the genus Callithrix. In A. B. Rylands (Ed.), Marmosets and tamarins: Systematics, behaviour, and ecology (pp. 262-271). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Snowdon, C. T. & Savage, A. (1989). Psychological well-being of captive primates. In E. F. Segal (Ed.), Housing, care, and psychological well-being of captive and laboratory primates (pp. 161-182). New Jersey: Noyes Publications.

----------

First author's address: Institute of Zoology, University of Vienna, Althanstrasse 14, A-1090 Vienna, Austria [e-mail: [email protected]].

----------

The conference will focus on the management and technology needs of the laboratory animal science community, emphasizing information pertinent to the day-to-day management of laboratory animal facilities and career development for managers, directors, and administrators. The meeting is open to anyone involved in the field of laboratory animal science, including institutional administrators, members of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees, laboratory animal veterinarians, investigators, researchers, regulatory personnel, managers, supervisors, and other staff who are responsible for laboratory animal care and use programs.

For additional information contact Carol Wigglesworth, Senior Policy Analyst, OLAW, Office of Extramural Research, NIH, RKL1, Suite 1050, MSC 7982, 6705 Rockledge Dr. [301-402-5913; e-mail: [email protected]]; or see <www.aalas.org/education/ meetings/MT_Conference/MT_Conf-index.htm>.

The Primate Society of Great Britain is having a one-day open meeting April 10, 2001, at the Bolton Institute, Bolton, Lancashire, England. This meeting is intended to reflect the diversity of current primatological research. Postgraduate research students particularly are encouraged to attend and give papers. For information or to offer a paper, contact Geoff Hosey, Biology and Environmental Studies, Deane Road, Bolton, BL3 5AB, UK [44 (0) 1204 903647; fax +44 (0) 1204 399074; e-mail [email protected]].

The American Society of Primatologists will hold the 2001 meeting in Savannah, Georgia. Armstrong Atlantic State University is sponsoring the event; our meeting will be the first to be held in the new science building that is currently under construction at Armstrong. The dates are Wednesday, August 8, 2001 (business meetings and the icebreaker), through Saturday, August 11, 2001. The banquet will be held Saturday evening at Historic Savannah Station. Information regarding the Savannah area can be located at <www.savannah-online.com/>.

Puzzle Ball Foraging Device for Laboratory Monkeys

Carolyn M. Crockett, Rita U. Bellanca, Kelly S. Heffernan*, Dennis A. Ronan, and Wayne F. Bonn

Regional Primate Research Center, University of Washington

Foraging is considered to be a crucial element in promoting psychological well-being in nonhuman primates. The USDA Draft Policy on Environmental Enhancement for Nonhuman Primates (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1999) specifies that environmental enhancement plans should provide for daily foraging opportunities. At the Washington Regional Primate Research Center (WaRPRC), we define a foraging experience as "any food or drink enrichment that requires extra manipulation and prolongs consumption time, thus providing mental stimulation." Simple food treats, such as small pieces of fresh produce, do not meet our definition of foraging. Food treats are given about four days per week (Bellanca et al., 1998). In addition, animals currently have periodic foraging experiences (usually at least once every week or two), primarily frozen treats and browse. Some animals are also provided with foraging devices. Two years ago, we recognized the need to enlarge our inventory of such devices to increase the laboratory primates' foraging experiences. If every cage were equipped with a foraging device, each could, in principle, be provisioned daily to meet the anticipated USDA Policy.

We wanted a foraging device that was inexpensive, durable, and effective, and that could be sanitized during routine cage washing. Psychological Well-being (PWB) Program staff worked with Colony Facilities Maintenance staff to design, fabricate, and test a device which we call the "Puzzle Ball". An earlier design of this foraging device was developed at WaRPRC (Murchison, 1992) and later modified at the Tulane RPRC to include three access holes (M. Murchison and S. Falkenstein, pers. comm.). The design described here includes modified access holes and a redesigned attachment. The final product has been in use at the WaRPRC since autumn of 1998.

The Puzzle Ball Foraging Device

The Puzzle Ball foraging device is constructed of stainless steel hardware and a commercially available plastic Boomer Ball(r) (Grayslake, IL), 4" to 4.5" in diameter (Figure 1). The original device had a single 0.75" diameter access hole (Murchison, 1992). We conducted observations to determine the appropriate number and size of holes (see next section). The final design included one 1" and two 0.75" diameter access holes, located above the midline and approximately equidistant from each other. The 1" hole provides easier access for larger fingers, including those of adult baboons, and provides a larger target for personnel provisioning the puzzle. We also found that Puzzle Balls sanitized while affixed to cages in the cage washer got cleaner with three access holes rather than two. Three holes above the midline appeared to allow more water to flush through the ball and out of the 3/8" drain hole at the bottom. The balls received from the supplier vary from 5/32" to nearly 3/8" in thickness and from 4" to 4.5" in diameter. This variation has not notably affected durability or use of the foraging device. We request that shipments include as many colors as are available, and our inventory of puzzle balls includes blue, red, yellow, orange, green, purple and turquoise. Although we have not tested whether color variation makes a difference to the monkeys, visitors and staff remark that it makes the housing rooms much more colorful and appealing.

Figure 1: : Puzzle Ball foraging device fabricated from a Boomer Ball(r) and stainless steel hardware. The standard nut is secured with a drop of Locktight(r).

Because non-stainless hardware used in some previous enrichment devices had rusted, we opted for stainless steel. The chain (six 1.25" links, 1/8" trade size, Type 316L; including bent and split links) was selected for strength and to minimize finger entrapment. The length, about 5.25", is short to avoid entanglement (Bielitzki, 1992). After considerable discussion and some experimentation, we decided that the Puzzle Balls would be attached permanently on the cages with a split link of the type of chain used to suspend the device. Sharp edges of the split links are deburred with a torch before use. Maintenance shop personnel invented a simple device to easily open and close the split link (Figure 2). Using brass locks (our standard cage locks) to attach the Puzzle Balls is too expensive, and snap hooks are too often removed by the monkeys. Several other attachments we tried were either flimsy or potentially hazardous. For example, the "Du Clip" (resembles a large paper clip) was removed by some animals, and caused at least one pinching injury, according to veterinary staff.

Another feature of the Puzzle Ball is its attachment to the chain with a self-locking nut. When worn out, the Puzzle Ball can be removed from the chain and easily replaced. The nuts and bolt can be recovered and used again. So far, only a few of the several hundred Puzzle Balls in use have had to be thrown away because of excessive damage from chewing. We cannot distinguish when individual balls have been placed in service, but most of those that are two years old are still in use.

Figure 2: : Stainless steel device for attaching Puzzle Balls: A. Open split link hooked on end of chain. B. Split link hooked over cage wire; slot of device is slipped over half of link to be closed and is turned (three slots allow various angles of leverage). C. Closed split link. Opposite action opens link.

The cost of the device is less than $8 in materials ($5 per ball; $2.20 for stainless steel hardware) and about 10 minutes of fabrication time. A recent batch of 85 Puzzle Balls was fabricated in 10 hours. Our goal is for all individual cages to have foraging devices, so permanent attachment is the least expensive option. Although we will eventually need one Puzzle Ball per individual cage, including empty ones in the cage wash cycle, the expense will be easily compensated for by the elimination of personnel time to move the devices from cage to cage.

Puzzle Balls are attached outside of the cage. Location of attachment varies from cage to cage. Those with food boxes located centrally below the cage door usually have the Puzzle Ball attached toward one side, above where the perch is installed. Those with food boxes to one side of the door often have the Puzzle Ball attached above the food box so that most spilled items fall in the hopper. However, husbandry staff request that the ball not be so close to the hopper opening that biscuit feeding is obstructed.

Testing the Device

Methods: Behavioral observations on four pigtailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina: two adult males, one adult female, one juvenile female) and three longtailed macaques (M. fascicularis: one adult male, two adult females) helped determine the final design of the Puzzle Ball. Each animal was observed for 10 minutes after six pieces of cereal were placed in the ball attached to that subject's cage. Three types of ball were presented to the subjects, a different one on each of three different days. Type A most resembled the "Tulane" model with three 0.75" holes. Type B had two 0.75" holes. Type C had two 1" holes. Behavior was recorded every 30 seconds using the instantaneous scan sampling method (Crockett, 1996).

Results: Overall, the subjects manipulated the Puzzle Ball during 69.5% of the scan samples. These observations also verified that the animals rarely manipulated the self-locking nut and were not able to remove it. Four of the seven subjects were able to successfully empty (eat plus spill) at least one type of Puzzle Ball in less than 10 minutes. (Most spilled about as much as they ate.) For the successful animals, it took an average of five minutes to empty the puzzle. The record was achieved by an adult female longtailed macaque who removed and ate all six pieces of cereal from a Type C puzzle in less than one minute. The other successful subjects were the second female longtailed macaque, and one adult male and the adult female pigtailed macaques. Across all seven subjects, the Puzzle Ball was emptied in less than 10 minutes in 35% of the trials; 57% of these cases were with the Type C ball. About 50% of the food was spilled from Type A ball, about 30% from Type B, and only 20% from Type C. In the end, we decided that one 1" hole and two 0.75" holes would be a good compromise, to facilitate cleaning, to provide holes for various finger sizes, and to add an element of choice. We have not conducted any follow-up observations to see if animals preferentially take food items out of the larger hole. We have verified that juvenile and adult baboons (Papio cynocephalus) are also adept at using the Puzzle Ball.

Effect of Puzzle Ball on Abnormal Behavior

Methods: Because the Puzzle Balls are being fabricated and placed on cages over a period of many months, we were able to conduct an informal study on some animals with and without the devices. Seventeen individually housed animals 3-11 years of age (12 male and one female M. nemestrina, two male and two female M. fascicularis) were observed for at least four 10-min observations with and four 10-min observations without the Puzzle Ball. These animals had been referred to the PWB Program for behavioral assessment; their behavior was scored on our standardized data sheet. We have found that four 10-min observations (30-sec scan samples) are sufficient to characterize behavior profiles of most animals referred for assessment (Bellanca et al., 1999). All observations were made when the ball was empty. Our intention was to see if the presence of the ball had any effect on abnormal behavior during periods when it was empty. In other words, we wanted to know if any beneficial effects of having a regularly provisioned device extended beyond the time animals were actually foraging. During the time these observations were made, less than half of the cages had Puzzle Balls. Because the Puzzle Balls are permanently attached, animals were rotated into cages with them and without them on an unpredictable basis. Because the number of devices increased over time, the majority of the "without Puzzle Ball" observations occurred before the "with Puzzle Ball" observations. Results: The presence of a Puzzle Ball was associated with a significant reduction in abnormal behavior (locomotor stereotypies, self-stimulation, and potential self-injurious behavior combined) in animals referred to the PWB Program for behavioral assessment. The median proportion of scan samples when the subjects engaged in abnormal behavior was .188 without the Puzzle Ball and .075 with the puzzle ball (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, z-statistic = 2.5, p= 0.012; Velleman, 1997). Even though the Puzzle Balls were empty during observations, the subjects did manipulate them, although an average of only 1.6% of the time. During the same observations (Puzzle Ball present), the subjects manipulated their portable cage toys (at least one per cage) an average of only 0.9% of the time. (Eight of 17 manipulated neither Puzzle nor toy.)

Discussion

An underlying policy of the WaRPRC's Psychological Well-being Program is to test enrichment methods before adopting them for general use. We incorporate research into most aspects of our environmental enhancement and behavioral assessment activities. The development of the Puzzle Ball foraging device also illustrates the essential collaboration between staff responsible for environmental enrichment and those responsible for maintaining caging and other colony facilities.

The Puzzle Ball has proven to be a durable and effective foraging device. It is inexpensive, easy to make, and easy to clean. The device is simple and requires more manual dexterity than mental acuity. However, it increases consumption time for all but the most dexterous animals. There is probably more spillage because the device has three holes rather than two, but we compromised on the side of easier sanitizing. Although we continue to use existing PVC tube puzzles (as described in Heath et al., 1992, and Murchison, 1991, as well as larger models), we are unlikely to replace them as they wear out. Such puzzles are more expensive, are more labor intensive to clean and move from cage to cage, and also obstruct more of the cage front. Even when empty, the Puzzle Ball is used as an anchored object of manipulation. The balls are handled, chewed, and batted, sometimes by animals in neighboring cages, occasionally inspiring minor aggressive interactions or affiliative touching. The most frequent signs of wear are tooth marks around the access holes. We have found that Boomer Balls last much longer when made into Puzzle Balls than when put inside cages.

Because animals are usually successful at removing food items from the Puzzle Balls, and because the three access holes and the drain hole permit water to flush through them during cage washing, residue rarely accumulates. However, we recommend avoiding sticky items (raisins, mini-marshmallows) or items likely to become gummy when wet (pasta, sugary cereals). Such items also stick to the floor when spilled. Peanuts and dry cereal are our usual provisioning items. Filberts are a good alternative for animals not allowed peanuts. Although some animals helpfully hold the Puzzle Ball to facilitate loading, most are not so cooperative. We have experimented with various "loading" devices, such as modified funnels, but have not yet found a successful one. It is definitely easier to provision the 1" hole than the 3/4" holes. Some animals are grabby, so personnel must be careful, as always when working with nonhuman primates. Double gloves are recommended, and we wear Tyvex sleeves when provisioning puzzles of animals with infectious diseases.

We were pleased that the empty Puzzle Balls were associated with a reduction in abnormal behavior. This is a somewhat surprising result because effects of foraging devices on abnormal behavior rarely extend beyond the time spent emptying them (Novak et al., 1998). However, because the "without Puzzle Ball" observations tended to occur earlier than those "with Puzzle Ball", we suspect that the present result reflects a general increase in psychological well-being due to increased enrichment over time, including regular provisioning of the Puzzle Ball. Although the Puzzle Ball is relatively simple, more difficult puzzles are not necessarily more beneficial. Instead of being mentally stimulated, animals may give up trying to solve them (Heath et al., 1992; Novak et al., 1998).

Meeting the proposed goal of daily foraging (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1999) can be facilitated by the use of foraging devices like the Puzzle Ball. Although our facility does not yet have them, we also support the idea of providing biscuits in forage feeders (Reinhardt & Garza-Schmidt, 2000). However, we do not believe that forage feeders can take the place of puzzle feeders, since the latter are provisioned with treat foods rather than regular biscuits. An ideal enrichment program would include both.

References

Bellanca, R. U., Crockett, C. M., Johnson-Delaney, C., DeMers, S. M., & Eiffert, K. (1998). Catering to catarrhines: Food enrichment at the University of Washington's Regional Primate Research Center. American Journal of Primatology, 45, 167-168.

Bellanca, R. U., Heffernan, K. S., Grabber, J. E., & Crockett, C. M. (1999). Behavior profiles of laboratory monkeys referred to a Regional Primate Research Center's Psychological Well-being Program. American Journal of Primatology, 49, 33.

Bielitzki, J. T. (1992). Letter to the editor: Enrichment hazards. Laboratory Primate Newsletter, 31, 36.

Crockett, C. M. (1996). Data collection in the zoo setting, emphasizing behavior. In D. G. Kleiman, M. E. Allen, K. V. Thompson, S. Lumpkin, & H. Harris (Eds.), Wild mammals in captivity: Principles and techniques (pp. 545-565). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Heath, S., Shimoji, M., Tumanguil, J. & Crockett, C. (1992). Peanut puzzle solvers quickly demonstrate aptitude. Laboratory Primate Newsletter, 31, 12-13. Murchison, M. A. (1991). PVC-pipe food puzzle for singly caged primates. Laboratory Primate Newsletter, 30, 12-14.

Murchison, M. A. (1992). Task-oriented feeding device for singly caged primates. Laboratory Primate Newsletter, 31, 9-11.

Novak, M. A., Kinsey, J. H., Jorgensen, M. J., & Hazen, T. J. (1998). Effects of puzzle feeders on pathological behavior in individually housed rhesus monkeys. American Journal of Primatology, 46, 213-227.

Reinhardt, V. & Garza-Schmidt, M. (2000). Daily feeding enrichment for laboratory macaques: Inexpensive options. Laboratory Primate Newsletter, 39, 8-10.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (1999). Animal welfare: Draft policy on environment enhancement for nonhuman primates. Federal Register, 64, 38145-38150.

Velleman, P. F. (1997). Data desk: The new power of statistical vision. Ithaca, NY: Data Description Inc.

----------

Authors' address: Regional Primate Research Center, Box 357330, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-7330 [e-mail: [email protected]]; *K. S. Heffernan is now at SNBL USA, Ltd. (Shinn Nippon Biomedical Laboratories, Ltd., Everett, WA 98203).

This research was supported by NIH grant RR00166. We thank N. Dickson and K. Hagerman for observation assistance; D. Shaw for inventing the attachment device; R. Shain for fabrication assistance; J. Gray for design input; K. Elias for editorial comments; and M. Domenowske for the illustrations.

----------

* * *

Workshop Announcements

Teaching Research Ethics

Indiana University's eighth annual Teaching Research Ethics Workshop will convene on the campus at Bloomington, Indiana, May 9-12, 2001. Session topics will include an overview of ethical theory; using animal subjects in research; using human subjects in clinical and non-clinical research; and responsible data management. Many sessions will feature techniques for teaching and assessing the responsible conduct of research.

For more information, contact Kenneth D. Pimple, Teaching Research Ethics Project Director, Poynter Center, Indiana Univ., 618 East Third St, Bloomington, IN 47405-3602 [812-855-0261; fax: 812-855-3315; e-mail: [email protected]]; or see [www.indiana.edu/~poynter/].

Orangutan Reintroduction and Protection

A workshop on Orangutan Reintroduction and Protection will be held June 15-18, 2001, at Wanariset-Samboja and Balikpapan, E. Kalimantan, Indonesia. It will mark the 10th anniversary of the Wanariset Orangutan Reintroduction Project (ORP). ORP is sponsoring this international workshop with the aims of presenting and evaluating its own operations and research over the last ten years, discussing future directions, and considering broader issues of orangutan conservation. For further information, abstract submission forms, or to discuss possible contributions, please contact Jeane Mandala, P.O. Box 500, Balikpapan 76103, Indonesia [+62 (0)542 413 069; fax: +62 (0)542 410 365; e-mail: [email protected]]; or Dr. A. Russon, Secretary, Scientific Advisory Board, Dept. of Psychology, Glendon College, 2275 Bayview Ave., Toronto, Ontario M4N 3M6, Canada Tel: [+1 416 736 2100 ext. 88363; fax: 1 416 487 6851; e-mail: [email protected]]. The deadline for abstracts is March 15, 2001.

* * *

Who's Enriching Whom? The Mutual Benefits of Involving Community Seniors in a Research Facility's Enrichment Program

Nancy Megna and Jessica Ganas

Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center Field Station and Antioch New England Graduate School

In hundreds of research facilities across the world live thousands of nonhuman primates that get lonely, bored, and frustrated. They often live in conditions which deprive them of the opportunity to express species-typical behaviors such as social interactions, foraging, and travel. These conditions can lead to abnormal behaviors such as self-mutilation, stereotypies, and depression. It is the duty of animal caretakers and veterinary and research staff to ensure that the psychological well-being of these animals is addressed. According to the Animal Welfare Act, Section 3.81, "Dealers, exhibitors and research facilities must develop, document, and follow an appropriate plan for environmental enhancement adequate to promote the psychological well-being of nonhuman primates."

In order to meet the needs of the 1700 nonhuman primates living in cages, runs, and compounds at the Yerkes Primate Research Center Field Station, located in Lawrenceville, Georgia, the authors, behavioral researchers Nancy Megna and Jessica Ganas, began APES, or "Alliance for Primate Enrichment by Seniors." Even though enrichment is required by law, time is often a major constraint for staff trying to create challenging and varied enrichment items for the animals. On the other end of the spectrum, time is something that nursing home residents have a lot of. We felt that perhaps seniors would be interested in creating enrichment treats for the Field Station's monkeys and apes. We contacted a local nursing home, the Medical Arts Health Facility in Lawrenceville, and spoke with the Director of Activities, Merri Kaye Robinson. After hearing what the program would entail, she enthusiastically agreed to help start APES.

The program began in January, 2000, with about ten residents who gathered for the first session. Since then, attendance has increased at each meeting. Often the seniors line up outside of their activities room ready to go before the session begins! The supplies used to make the enrichment treats are empty paper towel and toilet paper rolls collected by Yerkes employees, Dixie cups, and lunch bags. Food items are taken from the regular enrichment supplies of the Field Station or are donated by Yerkes employees or the nursing home. The foods include popcorn, nuts, pretzels, seeds, cereals, raisins, banana chips, currants, and uncooked noodles and rice. A mixture of items is placed in the cups, rolls or bags. Once the containers are half full, they are closed so that the food inside cannot be accessed without some effort by the animals. On their own, the seniors have divided duties based on manual dexterity. Some of the seniors crush items, some fill the cups, and some fold them closed. In one hour the seniors can make about 500 Dixie cups and 40 rolls, as well as many lunch bags.

Figure 1 Immediately, we began to notice how APES affected both seniors and primates. It has become the most highly attended activity at the Medical Arts Nursing Home; the level of enthusiasm is overwhelming. The seniors involved in the program take it very seriously. To them, this is their job - and they work very hard at it. They have gained a sense of self-worth and purpose because they are contributing to animal welfare. They take much enjoyment in repaying the animals for their contributions to medical research.

Figure 2: The apes and monkeys are benefiting tremendously from the program as well. The treats made for them are challenging - they have to work to get their food. There may be new treats inside each cup, bag, or roll, providing variety - and the food and paper both serve as enrichment. The care staff benefit from the time saved.

The residents at the Medical Arts Health Facility have contributed greatly to the well-being of Yerkes Field Station primates. The seniors deserved to be rewarded with more than a simple "Thank you," so we invited them to tour our facility. The mutual benefits of the program were apparent when seniors and primates were brought together, as shown by the residents' excitement and delight as they watched the primates enjoying the items they had prepared. Because some of the seniors are not ambulatory, we show them pictures and videotapes of the primates with the enrichment; some of the pictures are on a bulletin board at the nursing home. We will be scheduling more tours and thanking each senior with a certificate of appreciation in May during National Nursing Home Week.

The APES program has future plans. We will be expanding the repertoire of items that the seniors can prepare for the animals. Second, we plan to approach corporations and organizations for donations of food and/or materials. Third, we would like the Yerkes Main Center to participate in the program. We would also like to include other nursing homes in the area, since the program has been successful. Finally, by sharing our story of the program's success and demonstrating how easily it can be started and maintained, we hope to inspire other animal research facilities to start such programs.

* * *

----------

First author's address: 133 Sir Gregory Manor, Lawrenceville, GA 30044 [e-mail: [email protected]].

----------

* * *

Early vs. Natural Weaning in Captive Baboons: The Effect on

Timing of Postpartum Estrus and Next Conception

Janette Wallis and Buddy Valentine

University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

Introduction

The period following birth in baboons is characterized by cessation of the mother's reproductive cycles during the early phase of lactation. As in humans and anthropoid apes, nursing on demand tends to delay the resumption of reproductive cycles (Heinig et al., 1994; Vitzthum, 1994). As infants begin to suckle on a less consistent schedule, the mother's menstrual cycles resume.

When a wild infant baboon dies, regardless at what age, the mother typically resumes cycling within one month and becomes pregnant again within three months (Altmann et al., 1978). If the infant survives, however, lactation suppresses cycle resumption for about 12 months, although the infant may continue to suckle for up to 17 months (Altmann et al., 1977). In captivity, where nutrition is generally better than in the wild, cycle resumption has been reported to occur earlier - as early as six months postpartum (Rowell, 1966). At that age, the infant is still psychologically dependent on the mother, but eats enough solid foods to allow survival away from the mother. Thus, many laboratory facilities use six months (approximately 180 days) as an arbitrary age at which to separate infants from their mothers in the effort to stimulate the mother's reproductive cycles and maximize reproduction. At the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, this policy was in practice for a number of years.

In both human and nonhuman primates, however, infants can suffer serious and lasting effects when separated - for even a brief period - from their mothers (Kaufman & Rosenblum, 1967; Palloni & Millman, 1986). For baboons, weaning too early can have negative effects on a youngster's behavioral and physical maturation (Glassman & Coelho, 1988; Rhine et al., 1980). The optimal environment for any young primate is with its mother (Pazol & Bloomsmith, 1993).

In 1998, we began a program to enhance and expand our baboon resource program. In addition to establishing an environmental enrichment plan, we are assessing the efficacy of early infant weaning on both the reproductive performance of the overall colony as well as the behavioral well-being of individual baboons. An ongoing study compares the progress of social development in early (forcibly) weaned vs. naturally weaned infants (to be published elsewhere). The present study investigated the timing of infant removal and its influence on postpartum estrus and subsequent conception in captive baboons (Papio spp.).

Subjects and Methods

The subjects were baboons (Papio sp.) living at the Baboon Resource Center at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. Although detailed histories are lacking for many of these subjects, the majority of the baboons appear to be of the olive subspecies (Papio hamadryas anubis), with a possibility that some have mixed ancestry with yellow baboons (Papio h. cynocephalus).

From the colony records dating from March 1998 through August, 1999, we examined the details of 73 recorded pregnancies of 45 adult females. Of the 73 pregnancies under review, six were deemed apparent miscarriages, four were stillbirths, and five were neonatal deaths (by age 9 days; none occurred after that). In addition, four of the infants were removed for human rearing before five days of age due to incompetent maternal care. Only the time delay until onset of postpartum cycles was assessed for these 19 cases; none were used in the analysis of gestation length. The remaining 54 cases (live births) were assessed for the colony's gestation length. We used an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test for possible gender difference.

The subjects lived in five large social groups, in indoor, double-sided cages measuring 182 ft.2 each. The groups consisted of 10-12 adult females and various offspring. Three of the groups contained one adult male as a permanent resident, while the other two groups shared one male. The presence of a male influences the timing of reproductive parameters investigated in this analysis. In addition to the obvious parameters, such as time of conception and, consequently, parturition, a male's presence has even been reported to influence the timing of cycle resumption (Colmenares & Gomendio, 1988). Thus, for each analysis of these parameters, we omitted cases when a male was not present.

The past policy at this facility had been to forcibly wean infant baboons at approximately 180 days of age, and pair-house them with a like-aged peer. From March, 1998, to September, 1998, 21 infants were weaned at ages ranging from 167 days to 305 days. For the 18 cases involving an adult male living in the social group, we determined the following dates: conception, parturition, infant removal, onset of postpartum estrus, and next conception. Date of conception was arbitrarily estimated as the last day the mother exhibited full genital swelling, based on a number of studies which found ovulation to occur one or two days prior to detumescence (Gillman & Gilbert, 1946; MacLennan & Wynn, 1971; Hagino, 1974). Using these dates, we calculated the infants' ages at removal and several reproductive parameters. A Pearson's Correlation was used to determine the interrelationship between reproductive parameters. An ANOVA was used to assess the effect of forced weaning on these parameters.

Beginning in October, 1998, we ceased the routine practice of forcibly weaning infant baboons in our colony. Thus, we added to the analysis a comparison of reproductive parameters resulting when infants were forcibly weaned (regardless of age) vs. when infants remained with their mothers to be naturally weaned. There were 33 cases in the latter category. Only 21 of these included an adult male in the group and had subsequent reproductive events occurring during the period under review.

Results

The gestation length for 54 live baboon births was 181.6 ± 6.9 days. There were 32 female and 22 male infants. No twin births occurred and there was no gender effect on gestation length (female infants averaged 181.3 ± 7.2 days' gestation and males averaged 182.2 ± 6.6 days.

Predictably, in the 19 cases of miscarriage, stillbirth or early neonatal death (within 9 days), the mothers resumed having menstrual cycles quite rapidly. For these females, the first sign of postpartum estrous genital swelling appeared at an average of 28.5 days (range = 17-39 days). Effect of Early Weaning on Mothers' Cycles: For the 54 live births, there was a significant correlation between age at removal and duration from that time until postpartum estrus (r2 = -.72; p = .0007). This was a negative relationship, however; the earlier an infant was weaned, the longer it took for the mother to resume reproductive cycles. There was no correlation between infant removal age and the length of time to the next conception or birth.

Comparison of Age at Early Weaning: For cases in which infants were forcibly weaned, the data were divided into two groups: 8 infants removed at < 180 days of age (range 167-180 days), and 10 infants removed at > 180 days (range 181-305 days). The two groups differed somewhat in the time from infant removal to the onset of postpartum estrus, with the difference approaching significance (f = 4.16; p = .058). This finding resulted from the fact that postpartum cycles typically resumed before infant removal. Consequently, from the time of birth to the onset of postpartum estrus, the two groups showed no significant difference (mean of 173.4 and 167.7 days, respectively), nor were subsequent conception and parturition significantly influenced by time of infant removal. Comparison of Early Weaning vs. Natural Weaning: The 18 forced weaning cases (above) were compared to 21 cases in which infants were allowed to remain with their mothers to be naturally weaned. There was no significant difference between these two groups for the time between birth and the onset of postpartum estrus, the next conception, or the next parturition (Table 1). There was also no difference in the time between the onset of postpartum estrus until conception: 62.5 days vs. 59.0 days. Although none of these comparisons showed a statistically significant difference, the mean values were smaller for the naturally weaned cases than the forcibly-weaned cases (see Table 1).

| Weaned Early | Naturally Weaned | ANOVA | |

| Birth to Next Postpartum Estrus | 170.22 days (N=18) | 165.2 days (N=21) | F = .10 n.s. |

| Birth to Next Conception | 233.6 days (N=14) | 210.3 days (N=13) | F = 1.14 n.s. |

| Birth to Next Birth | 413.1 days (N=14) | 377 days (N=2) | F = 1.15 n.s. |

| Postpartum Estrus to Next Conception | 62.5 days (N=14) | 59.00 days (N=13) | F = .03 n.s. |

Table 1: Comparison of cases when infants were weaned early vs. when infants stayed with the mother for natural weaning

Only two births occurred during the study period to a mother who had naturally weaned her previous infant. The interbirth interval for those two cases averaged 377 days, compared to the average of 413.1 days for the other mothers. (For the live births that occurred after the study period, the mean for seven interbirth intervals was 384.9, still well below the figure when infants were removed.)

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that forced infant weaning did not improve reproductive productivity in our colony of baboons. In fact, the data indicate that most females resumed their reproductive cycles well before infant removal and, when given the opportunity for natural weaning, the females conceived while their previous infants were still dependent upon them (Table I). Based on these findings, we have encouraged the managers of our colony to allow natural weaning whenever possible. Unfortunately, some research protocols call for young subjects to live in small peer groups. Therefore, the colony managers' policy has not changed appreciably, although they have reduced pair-housing infants in favor of forming small peer groups.

The potential benefits of allowing infants to remain with their mothers throughout childhood are obvious. The first year of life for a baboon is a period of helplessness and dependency, during which the mother provides important companionship and care (Altmann, 1980). Rhine et al. (1984) suggested that the period centering upon the sixth month is a time when maturing motor, sensory, emotional, and exploratory systems are undergoing rapid integration with social learning. Cheney (1978) suggests that interactions with individuals of various ages other than the mother will facilitate the development of independence in a more relaxed and natural manner. Siblings and peers can provide a major source of social contact in early baboon life (Ransom, 1981). Allowing infants to be naturally weaned by their mothers provides crucial interaction that is required for normal behavioral and social development and, thus, may reduce the development of abnormal behavior. This is a key point for laboratory managers to consider. Because most captive research often focuses on the use of primates as "animal models" for humans, it is imperative that colony managers seek to produce the healthiest subjects possible. This must include attention to behavioral as well as physical health.

In addition to the benefits to psychological development, living in a complex social environment can facilitate learning skills for reproduction and parenting in baboons (Rhine et al. 1980; Hamilton et al., 1982). For example, our ongoing behavioral study indicates that infant males living with their mothers, in a mixed age social group, show playful attempts at sexual behavior (e.g., attempted mounting with erection) as young as one year of age. In contrast, we have a four-year-old forcibly weaned, human-reared male baboon who has yet to show any indication of sexual interest despite his living with many adolescent females (J. Wallis, unpublished data).

The results of this study may be a consequence of several changes in the subjects' environment. In addition to allowing natural weaning when possible, we have implemented a new enrichment program. Among other activities, our enrichment plan includes provision of novelty food items and the addition of climbing structures in the cages. The occasional food treats help to supplement the infants' normal diet. For baboons in the wild, a major determinant of weaning age is the availability of easily eaten "weaning foods" to supplement milk (Altmann 1980). Thus, through the novel treats, we may be providing enough supplemental foods to slightly alter suckling patterns.

The added climbing structures, inexpensively constructed with PVC pipe, metal conduit, and chain, enhance the use of vertical space, thus reducing crowding. Wilson (1972) noted that the number and complexity of structures present in captive primate environments are more important than the actual size of the enclosures. Adding moveable and nonmoveable objects to captive baboon cages results in higher levels of activities such as play and locomotion (Kessel & Brent, 1996). The benefits of such social play include the development of motor skills and facilitation of communication leading to social bonding (Fagen, 1993). Together, the reduced stress, increased motor activity, and presence of many infants of various ages approximates a more species-normal social group and may facilitate reproductive success and psychological well-being (Novak & Suomi, 1991).

The findings of this study suggest that the best strategy for baboon breeding programs is to allow natural weaning whenever possible. The benefits include:

Reproduction: Reproductive output for the naturally weaned group is comparable to that of the forcibly weaned group.

Management: Group housing reduces the use of individual or pair housing, which in turn reduces the animal care workload: cleaning and feeding of gang cages tends to be less time-consuming than care of individually caged subjects.

Compliance: Maintaining larger and more complex social groups allows for better compliance with the USDA guidelines (USDA, 1999).

Psychological well-being: Allowing infant baboons to stay with their mothers and grow up in a socially complex setting provides the opportunity for the development of more natural and normal social behavior.

References

Altmann, J. (1980). Baboon mothers and infants. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Altmann, J., Altmann, S. A., & Hausfater, G. (1978). Primate infant's effects on mother's future reproduction. Science, 201, 1028-1030.

Altmann, J., Altmann, S. A., Hausfater, G., & McCuskey, S. A. (1977). Life history of yellow baboons: Physical development, reproductive parameters, and infant mortality. Primates, 18, 315-330.

Cheney, D. L. (1978). Interactions of immature male and female baboons with adult females. Animal Behaviour, 26, 389-408.

Colmenares, F. & Gomendio, M. (1988). Changes in female reproductive condition following male take-overs in a colony of hamadryas and hybrid baboons. Folia Primatolgica, 50, 157-174.

Fagen, R. (1993). Primate juveniles and primate play. In M. E. Periera & L. A. Fairbanks (Eds.), Juvenile primates: Life history, development, and behavior (pp. 182-196). New York: Oxford University Press.

Gillman, J. & Gilbert, C. (1946). The reproductive cycle of the chacma baboon (Papio ursinus) with special reference to the problems of menstrual irregularity as assessed by the behaviour of the sex skin. South African Journal of Medical Sciences, 11, 1-54.

Glassman, D. M. & Coelho, A. M., Jr. (1988). Formula-fed and breast-fed baboons: Weight growth from birth to adulthood. American Journal of Primatology, 16, 131-142.

Hagino, N. (1974). Follicular maturation, ovulation, luteinization and menstruation in the baboon. In E. M. Coutinho & F. Fuchs (Eds.), Physiology and genetics of reproduction, Part A (pp. 323-342). New York, Plenum. Hamilton. W. J., Busse, C., & Smith, K. S. (1982). Adoption of infant orphan chacma baboons. Animal Behaviour, 30, 29-34.

Heinig, M. J., Nommsen-Rivers, L. A., Peerson, J. M., & Dewey, K. G. (1994). Factors related to duration of postpartum amenorrhea among USA women with prolonged lactation. Journal of Biosocial Science, 26, 401-409.

Kaufman, C. I. & Rosenblum, L. A. (1967). Depression in infant monkeys separated from their mothers. Science, 155, 1030-1031.

Kessel, A. L. & Brent, L. (1996). Space utilization by captive-born baboons (Papio sp.) before and after provision of structural enrichment. Animal Welfare, 5, 37-44.

MacLennan, A. H. & Wynn, R. M. (1971). Menstrual cycle of the baboon: I. Clinical features, vaginal cytology and endometrial histology. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 38, 350-358.

Novak, M. A. & Suomi, S. J. (1991). Social interaction in nonhuman primates: An underlying theme for primate research. Laboratory Animal Science, 41, 308-314.

Palloni, A., & Millman, S. (1986). Effects of interbirth intervals and breastfeeding on infant and early childhood mortality. Population Studies, 40, 215-236.

Pazol, K. A. & Bloomsmith, M. A. (1993). The development of stereotyped body rocking in chimpanzees reared in a variety of nursery settings. Animal Welfare, 2, 113-129.

Ransom, T. W. (1981). Beach troop of the Gombe. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press.

Rhine, R. J., Norton, G. W., Roertgen, W. J., & Klein, H. D. (1980). The brief survival of free-ranging baboon infants (Papio cynocephalus) after separation from their mothers. International Journal of Primatology, 1, 401-409.

Rhine, R. J., Norton, G. W., & Westlund. B. J. (1984). The waning of dependence in infant free-ranging yellow baboons (Papio cynocephalus) of Mikumi National Park. American Journal of Primatology, 7, 213-228.

Rowell, T. E. (1966). Forest living baboons in Uganda. Journal of Zoology, 149, 344-364.

United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. (1999). Final report on environment enhancement to promote the psychological well-being of nonhuman primates.

Vitzthum, M. J. (1994). Comparative study of breastfeeding structure and its relation to human reproductive ecology. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 37, 307-349.

Wilson, C. C. (1972). Spatial factors and the behavior of nonhuman primates. Folia Primatologica, 18, 256-256.

----------

Corresponding author: Janette Wallis, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, P.O. Box 26901, Oklahoma City, OK 73026 [e-mail: [email protected]].

We acknowledge the support of the OUHSC Baboon Resource Center animal care staff, W. Hill, G. Spiegel, P. Griffith, and J. Weigant, as well as the veterinary staff, G. White, R. Wolf, and M. Cary. We wish to dedicate this paper to the memory of Ray Rhine, who taught the world so much about young baboons and what makes them tick. This work was supported by NIH/NCRR grant RR12317-01A1.

----------

The following responses were received:

From Jo-Ann C. Jennier, Jackson Zoo [[email protected]]: Our red-ruffed lemurs love to hang from the top of their cage by their hind feet. Perhaps you could try hanging treats (e.g., sweet potato) from a low tree limb to elicit this fascinating behavior. This would be enriching for both the lemurs and the observers.

From: JoAnne Kowalski, Philadelphia Zoo [[email protected]]: We've used coated mesh to make feeders. Basically just make a box out of it and cut holes in it large enough for the lemurs to get the food out in their fists. You can also drill holes in the side of PVC piping and put screw-on caps on each end. Hang them up as feeders. Depending on the species, some lemurs will like to have browse to mess with. You can also freeze fruit, make ice cubes with pieces of fruit, or bigger blocks of ice with food in it. You can also check on different foods to use - blueberries, peas, Cheerios, raisins, corn, green beans, etc. Hope this helps.

From: Jo Fritz, Primate Foundation of Arizona [[email protected]]: Try the National Academy of Sciences' Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as a beginning point. You can access it at <www.nap.edu/readingroom/books/labrats/>. For environmental enrichment, there are several places, but start with: the Animal Welfare Information Center: <www/nal.usda.gov.awic>; Dr. Viktor Reinhardt: <www.animalwelfare.com/Lab-animals.biblio/enrich.htm>; and the Primate Enrichment Web Site: <www.brown.edu/Research/Primate/enrich.html>. For general primatology questions try AskPrimate: <primate.wisc.edu/pin/askprim.html>; the American Society of Primatology: <asp.org>; Living Links Web Site: <www.emory.edu/LIVING-LINKS/>; Sci-Web, the Life Science Home Page: <www.sciweb.com>; The Electronic Zoo: <netvet/wustl.edu/e-zoo.html>; or the World Wide Web Virtual Library's Biotechnology Information: <www.cata.com/biotech>.

From Bob Lewis, former caretaker, [[email protected]]: Puzzle feeders can be found at the Primate Products Website: <www.primateproducts.com/products/prod03.html>. These expensive doodads are hung on the outside of the cage. The animal routes food and treats through a maze. Do NOT do like a former supervisor of mine and place a puzzle feeder IN the cage with a primate - in this case, a female rhesus macaque. Your US$200 investment will end up in the rubbish as scraps of polycarbonate plastic.

From: Ian Colquhoun, University of Western Ontario, Scientific Advisor to the Black Lemur Species Survival Plan [[email protected]]: It should be remembered that "environmental enrichment" can be achieved in some respects through straightforward, low-tech (i.e., "inexpensive") measures. With lemurs, we are dealing with arboreal species. A basic bit of environmental enrichment would be to ensure that they have as complex a system of raised substrata as possible, to the extent that the size of the enclosure(s) and the management protocols of the animal care staff allow. That is, give them lots of branches, of various diameters and set at various angles - ideally, you'd be trying to reconstruct the three-dimensional complexity of a tree canopy to the best extent possible. As a graduate student, I spent several summers working on the animal care staff of a small, seasonal municipal zoo. I earned the title "branch manager" from colleagues thanks to my drive to provide as many raised supports as possible for the zoo's primates. But, the proof was in the pudding, as they say - the branches were used and definitely gave the animals options on their use of space and time outside of the periods that food was being consumed.

News Briefs

Ape Caper Foiled

Washington, D.C.: A male orangutan named Junior made a brief escape from the National Zoo's Great Ape House and zoo visitors were warned away from the area until he was recaptured. Junior is about 30 years old and had never before left the Ape House, zoo officials said, even though there are a series of towers orangutans can use to go back and forth between that enclosure and the zoo's animal Think Tank.

Keepers were "astonished" when Junior climbed out on one of the 40-foot towers and managed to escape, said zoo spokesman Robert Hoage. The animal got out about 11:45 a.m. and headed in the direction of the zoo police station, Hoage said. His absence was almost immediately detected. About 22 minutes later, the orangutan was "darted" with a tranquilizer gun fired by a veterinarian. The tranquilized animal was to be examined and officials said he might be back on exhibit as early as that afternoon.

The towers the animals climb are surrounded by electric "hot" wires to keep them from straying into the park. If the wires fail, lights are supposed to come on to alert keepers. "We have to learn if the power went off or if he defeated the system," Hoage said.

During Junior's escape, zoo visitors were cleared away from the area and confined to a section of the zoo near the Elephant House. - From the Washington Post, August 29

Death of a Chimpanzee at Coulston

Dr. M. K. Izard, Director of Behavioral Enrichment at the Coulston Foundation, posted an announcement to Alloprimate on September 13 about the death of Ray, a chimpanzee owned by NIH and under the care of the Coulston Foundation. "Ray was an HIV-exposed animal. On Wednesday, he was noted to be hypoactive with pale lips and gums. He had a normal appetite. On Thursday, he had a good appetite and normal stool. He was scheduled for a physical exam on Friday, yet was found dead that morning. Pathology reports show that Ray died of a systemic fungal (Coccidiodes immitis) infection that is fatal to an immunosuppressed host. Treatment would have been unsuccessful due to the progressive nature of this disease."

Anna Mae Noell, Owned "Chimp Farm"

Anna Mae Noell, who with her late husband owned and operated Noell's Ark Chimp Farm in Palm Harbor, Florida, died October 15. She was 86. The couple ran the popular and sometimes controversial roadside zoo since 1971.

Billing their farm as a retirement home for many cast-off primates, the Noells developed a reputation for taking in abandoned, old, and sick animals - mostly apes and monkeys - from small zoos and private owners. Mr. Noell died in 1991.

In recent years, state and federal officials, as well as several animal rights activists, criticized the facility for keeping animals in poor conditions. Last year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture permanently revoked the sanctuary's permit to show the animals to the public.

Now called the Suncoast Primate Sanctuary, the facility is run by a private, non-profit organization. The organization recently broke ground for a new primate facility, and volunteers there hope that it will lead to a reinstatement of the license to exhibit the animals. The sanctuary is home to 27 chimpanzees, three orangutans, two gorillas, 21 monkeys, a bear, two turtles, two alligators and two goats. - from an article by Robert Farley in the October 17 St. Petersburg Times, posted to Alloprimate by Hope Walker

LEMSIP Chimps Retire to Texas

Carol Asvestas announced October 25 on Alloprimate that the National Sanctuary for Retired Research Primates has received eight of 16 chimpanzees due to be retired. They arrived on October 19. The remaining eight will arrive December 10th. These chimps were not a social group, so great lengths were taken to make sure socialization was successful. Because of the help given by Dr. Thomas Rowell, Dr. James Mahoney (who stayed a week to be certain all was well), Dr. Dana Hasselschwert, and Chief Technician Danny Bouttay, the transfer and socialization were successful and without incident. The chimps, originally at LEMSIP, were being temporarily housed at New Iberia Research Institute. The animals were socialized within three and a half hours and are doing beautifully. "I can't tell you how much it meant to us and the chimps to have the support from these wonderful caring people. I thank them all for their amazing efforts and this incredible achievement."

Three New Lemur Species

Scientists from the United States, Germany, and Madagascar have announced that they have discovered three previously unknown species of mouse lemurs (see abstract on page 35). Lemurs are among the world's most endangered species. The newly discovered lemurs represent a small but encouraging sign to conservationists. - From an Associated Press announcement, posted to Alloprimate, November 14

Clinton Signs Great Ape Conservation Bill Into Law

On November 1, President Clinton signed into law H.R. 4320, the Great Ape Conservation Act of 2000, that will provide funding for conservation programs designed to protect chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans. The bill authorizes $5 million in annual U.S. aid to support conservation and protection of the great apes by allocating grants to local wildlife management authorities and other organizations in Africa and Asia dedicated to protecting the apes and their habitat. Although habitat destruction is the major threat to great ape populations, unregulated hunting and the international bushmeat trade pose an even greater threat in many areas. While national laws prohibit the hunting of great apes in most cases, forestry and wildlife officials often lack the basic resources required for enforcement. Funding through this Act will bolster projects aimed at strengthening law enforcement and by providing necessary resources and training for park officials in Africa and Asia. - From a Humane Society press release, posted to Alloprimate, November 5

Only the Latin binomial has any "right" or "wrong". Even here there will be disagreements and proposed names. The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature will make decisions from time to time based on various principles. Their position, however, is that there is no right or wrong for common or "trivial" names. Howler, howling, and "black monkey with five fingers" are all equally good. So are the names in non-English languages. Brachyteles is the muriqui is the wooly spider. Macaca fascicularis is the long tail macaque, longtailed macaque, cyno, irus, kra, kera, Java, Phillipine, etc. I always say the grammatically incorrect thing when I talk of pigtail monkeys. Pigtailed, berok, or such have no greater validity. We all have our favorite names. As long as we mention the Latin binomial on first usage, we can call it whatever we wish. I note that in Belize they call howler monkeys "baboons". Certainly not desirable from my perspective, but not "wrong". You will notice a certain perverse consistency in common names so that if a scientific name becomes invalid some people will use it as the common name. This is the origin for rhesus, cynomologus, irus, etc. Some people now even refer to Macaca arctoides as speciosa, instead of the bear macaque, stumptail, stumptailed, or miniature chimp (a reference in an old Montgomery Ward's catalog offering them for sale as pets).

Best regards, Irwin Bernstein, Dept of Psychology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA [e-mail: [email protected]].

* *

Howler - Howler Monkey - Howling Monkey: Is there a legitimate reason for preferring one over the other? What rules apply to determining common names? Several years ago I was confronted with this controversy. I wrote an article for an International Journal of Primatology issue on howlers (1998, 19[3]). Throughout, I used the common name "howler monkey" as had been my practice in previous papers. The guest editor of the collection, Margaret Clarke, and the editor of the journal, Russ Tuttle, insisted on "howling monkey." Katharine Milton, another contributor to the issue, and I lobbied hard for "howler monkey," but to no avail. In the end, Russ Tuttle decided that we could use "howling monkey" or "howler," but not "howler monkey." This was his editorial decision.

"Howling monkey" is not based on any preponderance of use or compelling grammatical argument that I can detect. Clarence Ray Carpenter initially used "howling monkey" but switched to "howler monkey" in his later works. To my mind, a "howling monkey" is a monkey that is howling; a "howler monkey" is a monkey capable of howling (and especially notable for this behavior). Common names of other fauna and flora do not reveal a consistent pattern. There are "digger wasps," "song sparrows," and "sting rays." But there are also "chipping sparrows" and "stinging nettles." In fact, relatively few living things are named after their behavior; most are named for appearance (woolly monkey) or after a person (Goeldi's monkey). So the issue comes down to personal preference.

We could solve the problem by using "howler" exclusively. At least one other creature I can think of has a name equivalent to "howler": the "screamer" of South America. It's a bird, but it is not called the "screamer bird." There is no other creature called "howler," so the additional descriptor "monkey" is not really necessary. As for "howling monkey," it sounds grating and strange to me, much as "howler monkey" must sound to the "howling" proponents. - Carolyn M. Crockett, Regional Primate Research Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-7330 [e-mail: [email protected]].

* *

Given this assortment of advice, We will exercise our editorial prerogative: Authors may call monkeys by whatever common name makes them happy (except "pigtail" macaques, which has personal connotations for Us...make that "pigtailed", please), so long as they start with the Latin binomial. - The Editors

* * *

Awards Granted

PCWS Conservation Grant

The Primate Conservation and Welfare Society has announced the award of their first annual Primate Conservation Grant. The grantee, Mr. Nicholas Malone, is a graduate student at Central Washington University. His project is "Population Assessment of Displaced Hylobatids and Monitoring the Trade of Primates in Indonesia". Mr. Malone's application was reviewed by the PCWS Board of Directors as well as three outside reviewers. His project is an effort to monitor the sale of primates at various "bird markets" in Java and Bali and to conduct genetic analysis to develop a comparative database for future research. Investigations such as Mr. Malone's, working in collaboration with local people and NGO's, is a vital link in the long-term survival of highly endangered species.

Several other very worthy projects did not receive funding due to PCWS's funding limitations. PCWS plans to continue the small grant project in the years to come and would like to thank all of the PCWS Conservation Auction bidders who made this grant possible, as well as those who applied for funding.

Details of Mr. Malone's project, as well as some amazing photos from Indonesia, will be available in the next issue of Faces From the Forest - the PCWS newsletter. For your copy contact: [[email protected]].

NCRR Primate Grants

Among the more than 1000 new grants awarded in Fiscal Year 2000 by the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), NIH, were the following:

* To help meet the increased demand for specific-pathogen-free (SPF) macaques for AIDS research, NCRR is funding five SPF rhesus macaque colonies at NCRR-supported primate centers in Massachusetts, Puerto Rico, Texas, Oregon, and California.

* A $2.5 million, five-year grant to the Primate Center Library at the Wisconsin RPRC will fund Coordinated Information Services for Primate Research. Headed by WRPRC Librarian Larry Jacobsen, the services will promote rapid sharing of information among primate researchers.

Applications should be sent on a form to be obtained from the Foundation, and will include: a C.V.; a list of publications of the applicant; the names of two senior scientists whom the applicant has asked to send testimonials to the Secretariat of the Foundation by the date indicted below; and a letter of acceptance from the inviting laboratory.

Fifteen copies of the completed files should be sent to the Secretariat of the Foundation, 195, rue de Rivoli, 7500l Paris, France. Deadline for receipt of applications by the Foundation: March 30, 2001.

2001 International Prize

An International Prize of 300.000 FF is awarded annually to a scientist who has conducted distinguished research in the areas supported by the Foundation. This prize was awarded in 1980 to Professor Andre Leroi-Gourhan; in 1981 to Professor William H. Thorpe; in 1982 to Professor Vernon B. Mountcastle; in 1983 to Professor Harold C. Conklin; in 1984 to R. W. Brown; in 1985 to P. Buser; in 1986 to D. Pilbeam; in 1987 to D. Premack; in 1988 to J. C. Gardin; in 1989 to P. S. Goldman-Rakic; in 1990 to J. Goody; in 1991 to G. A. Miller, in 1992 to P. Rakic; in 1993 to L. L. Cavalli-Sforza; in 1994 to L. R. Gleitman; in 1995 to W. D. Hamilton; in 1996 to C. Renfrew; in 1997 to M. Jouvet; in 1998 to A. Walker; and in 1999 to B. Berlin. Discipline considered for the 2001 prize: Comparative Ethology.

Nominations must be proposed by recognized scientists, and should include: a C.V. of the nominee; a list of his publications; and a summary (four pages maximum) of the research work upon which the nomination is based. Nominations should be sent in 15 copies to the Secretariat of the Foundation, 194, rue de Rivoli, 7500l Paris, France. Deadline for receipt of nominations: October 31, 2001.

La Universidad de la Habana, Sociedad Cubana de Antropología Biológica, Museo Antropológico Montané, Cátedra de Antropología Luis Montané y la Asociación Antropológica de Estudios Primatológicos: Eopithecus de México, les hacen una cordial invitación, al VII Simposio de Antropología Biológica "Luis Montané" y al III Congreso Los Primates como Patrimonio Nacional, durante el 26 de Febrero al 2 de Marzo del 2001,en la Universidad de la Habana, Cuba.

Esperamos contar con gran asistencia en el evento que incluirá las siguientes formas de participación: conferen-cias magistrales por invitación, mesas redondas, comunicaciones orales, y carteles científicos.

Inscripción: El pago de la inscripción al congreso se hará al registrarse en la Universidad de La Habana. Las tarifas son: Titular: US$100, Estudiante: US$50, Acompañante: US$70.

Correspondencia en México para el Congreso Los Primates Como Patrimonio Nacional III, con Braulio A. Hernández Godínez, [e-mail: [email protected]] y en La Habana, Cuba, para el VII Simposio de Antropología Física "Luis Montané", con el Lic. Armando Rangel Rivero, Secretario Ejecutivo Museo Antropológico Montané, Facultad de Biología, Universidad de La Habana, Calle25#455, entre J e I. El Vedado, Ciudad de La Habana 10400, Cuba [e-mail: montaneqcomuh.uh.cu].

Reflexiones sobre la relación hombre-mono en las diferentes culturas. Arturo González-Zamora. Maestría en Manejo de Fauna Silvestre, Instituto de Ecología A.C., Xalapa, Veracruz, México [e-mail: [email protected]].

Desde tiempos ancestrales, la relación que ha existido entre el hombre y la naturaleza ha quedado plasmada en grabados, motivos cerámicos, trabajos en metal, petroglifos, y otras manifestaciones culturales; indicando que para el hombre, la naturaleza no sólo representaba la base material que cubría sus necesidades básicas, sino que constituía un estimulo para sus emociones.