|

The News Service | |||

News | ||||

|

Brown Grad Student’s Seismic Study Shakes Up Plate Tectonics

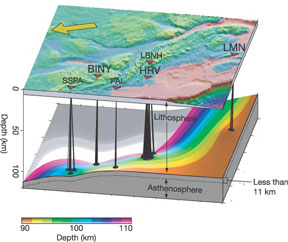

In a surprising study in Nature, a team led by a Brown University graduate student shows that a sharp boundary exists between the Earth’s hard outermost shell and a more pliable layer beneath, a difference in geological strength underpinning plate tectonic theory. The findings are strong evidence that temperature alone can’t account for differences between the regions, which allow plate tectonics to occur. PROVIDENCE, R.I. — Earth’s cool, rigid upper layer, known as the lithosphere, rides on top of its warmer, more pliable neighbor, the asthenosphere, as a series of massive plates. Plates continuously shift and break, triggering earthquakes, sparking volcanic eruptions, sculpting mountains and carving trenches under the sea. But what, exactly, divides the lithosphere and the asthenosphere? In the latest issue of Nature, a trio of geophysicists from Brown University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology publish research that sheds new light on the nature of the boundary between these rocky regions.  Where even rock is weaker Lead author Catherine Rychert, a 26-year-old graduate student in Brown’s Department of Geological Sciences, found a sharp dividing line between the lithosphere and the asthenosphere, according to data culled from seismic sensors sprinkled across the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. Rychert and colleagues discovered that sound waves recorded by the sensors slow considerably about 90 to 110 kilometers below ground – a sign that the rock is getting weaker and that the lithosphere is giving way to the asthenosphere. Within in a distance of a mere 11 kilometers – roughly 7 miles or less – the transition is complete. This evidence runs contrary to the prevailing notion that the lithosphere-asthenosphere transition is a gradual one. It also points up the fact that temperature alone cannot define the boundary. Rychert said that water or a small amount of partly molten rock must also be present in the asthenosphere to cause such an abrupt change in the mechanical strength of the rock. “These findings will be controversial because they run counter to what some scientists believe is true,” Rychert said. “Regardless, they’re pretty cool. We know something new, literally, about the earth under our feet.” To conduct the study, Rychert gathered seismic data from hundreds of earthquakes recorded during more than five years at six government-operated or university-run research stations in Canada, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York and Pennsylvania. She modeled and analyzed the data with the assistance of Karen Fischer, the Royce Family Professor of Teaching Excellence and professor of geological sciences at Brown, and Stéphane Rondenay, the Kerr-McGee Assistant Professor of Seismology at MIT and a former postdoctoral research fellow at Brown. The project took three years to complete. “We initially were very surprised by the sharpness of the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary indicated by the data,” said Fischer, “and so I challenged Kate to prove that such a rapid transition is definitively required. All of her careful modeling has now paid off with a result that makes a fundamental contribution to our understanding of the Earth’s lithosphere.” The Geophysics Program at the National Science Foundation funded the work. ###### News Service Home | Top of File | e-Subscribe | Brown Home Page | ||||