|

September 14, 2006 |

Oldest Writing in the New World Discovered in Veracruz, Mexico

A stone block discovered in the Olmec heartland of Veracruz, Mexico, contains the oldest writing in the New World, says an international team of archaeologists, including Stephen D. Houston of Brown University. The team determined that the block dates to the early first millennium B.C.E. – at least 400 years earlier than scholars previously thought writing existed in the Western hemisphere. The findings are published in Science. | |||

|

Brown University Home |

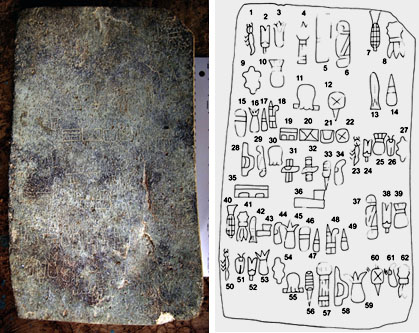

PROVIDENCE, R.I. — New research published this week in Science details the discovery of a stone (serpentine) block in Veracruz, Mexico, containing a previously unknown system of writing, thought to be the earliest in the New World. An international team of archaeologists, including Brown University’s Stephen D. Houston, determined that the slab – named the “Cascajal block” – dates to the early first millennium B.C.E. and has features that indicate it comes from the Olmec civilization of Mesoamerica. They say the block and its ancient script “link the Olmec civilization to literacy, document an unsuspected writing system, and reveal a new complexity to this civilization.”  New World’s oldest writing “It’s a tantalizing discovery. I think it could be the beginning of a new era of focus on Olmec civilization,” said Houston, an expert on ancient writing systems and corresponding author for the Science article. “It’s telling us that these records probably exist and that many remain to be found. If we can decode their content, these earliest voices of Mesoamerican civilization will speak to us today.” Road builders first discovered the Cascajal block in a pile of debris heaped to the side of a destroyed area in the community of Lomas de Tacamichapa in the late 1990s. Mexican archaeologists Carmen Rodríguez and Ponciano Ortíz, lead authors of the article in Science, were the first to recognize the importance of the find and to register it officially with the Goverment authority, the Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia of Mexico. Surrounding the piece were ceramic sherds, clay figurine fragments, and broken artifacts of ground stone, which, in addition to “internal clues” and “regional archaeology,” have helped the team date the block and its text to the San Lorenzo phase, ending about 900 B.C.E. That’s approximately 400 years before writing was thought to have first appeared in the Western hemisphere. Carved of the mineral serpentine, the block weighs about 26 pounds and measures 36 cm long, 21 cm wude, and 13 cm thick. The incised text consists of 62 signs, some of which are repeated up to four times. Because of its distinct elements, patterns of sequencing, and consistent reading order, the team says the text “conforms to all expectations of writing.” “As products of a writing system, the sequences would, by definition, reflect patterns of language, with the probable presence of syntax and language-dependent word order,” the article states. Five sides on the block are convex, while the remaining surface containing the text appears concave; hence, the team believes the block has been carved repeatedly and erased – a discovery Houston calls “unprecedented.” Several paired sequences of signs also lead the researchers to believe the text contains poetic couplets which would be the earliest known examples of this expression in Mesoamerica. In addition to Houston, the research team includes some of the world’s top experts on Olmec civilization, ceramics, and imagery: Ma. del Carmen Rodríguez Martínez and Alfredo Delgado Calderón of the Centro del Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia of Mexico; Ponciano Ortíz Ceballos of the Instituto de Antropología de La Universidad Veracruzana; Michael D. Coe of Yale University; Richard A. Diehl of University of Alabama; and Karl A. Taube of University of California-Riverside. High-resolution photographs of the Cascajal block and other graphics are available by contacting the Office of Media Relations at (401) 863-2478. Contact information for research team:

###### | |||