|

September 5, 2007 |

Arts and humanities departments welcome 14 new faculty

Fourteen new members of the regular faculty are beginning work in arts and humanities at Brown this fall:

Ömür Harmansah in Archaeology and Egyptology;

James Fitzgerald in Classics;

Jacques Khalip and

Vanessa Ryan in English;

Aldo Mazzuchelli in Hispanic Studies;

Jorge Flores in History;

Douglas Nickel in History of Art and Architecture;

John Cayley in Literary Arts;

Kiri Miller in Music;

Katherine Dunlop and

David Christensen in Philosophy;

Thomas Lewis in Religious Studies;

Michael Oklot in Slavic Languages; and

Ed Osborn in Visual Art.

| |||

|

Brown University Home |

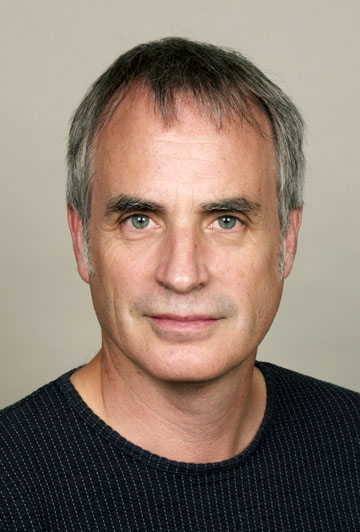

John Cayley Having gained recognition as a “digital writer” – or as he sometimes says, “literal artist” John Cayley comes to Brown’s Literary Arts Program to help push an innovative, pioneering department even further. “Brown is the pioneer and Brown should remain the point of reference in the academic world for writing in digital media,” Cayley says. Part of his task at Brown will be to ask tough questions in this emerging field, he says. “What will or will not emerge as a widely recognized genre of writing from all the ephemeral new forms and experiments that proliferate across the Net and on the screens of our electronic familiars? How will all this change our notion of what writing is and how writing is made? Writing in and for a 3-D virtual world? It’s here now, and it will come.” Cayley completed his studies in East Asian languages and literature (Chinese) at the University of Durham in England, experimenting in the early personal computer with acrostic and mesostic generated text. It was there that his innovative connection with poetry and the computer began. He continued his research and studies at the University of Newcastle, publishing his earliest poems and translations, becoming a curator at the British Library for Oriental Collections, Chinese section. Cayley went on to become a director and shareholder of Hanshan Tang Books, and subsequently launched his own Wellsweep Press, as a well recognized poet, publishing in print, but working primarily in networked and programmable media. Cayley is also an honorary research associate of the English Department of Royal Holloway College, University of London, and an honorary fellow at Dartington College of Arts. It is difficult to find a language to describe his works – but some sense comes from the titles: wotclock, a text-generating speaking clock, riverIsland, a navigable text movie, and wine flying, exploring some of the poetic structures underlying a single, classical Chinese quatrain. As Cayley himself says, “It is tremendously exciting to be deeply involved in what is still a new and less well-understood field of study and artistic practice. There are big issues at stake and difficult problems to address.” – Molly de Ramel

David Christensen David Christensen has spent much of his scholarly career imagining what ideal rationality would be like. He says many philosophers have traditionally thought that ideally rational belief respects logic and therefore, all the things one believes should be logically consistent with one another. But this presupposes that belief is an all-or-nothing matter: Either you believe something, or you don’t. “I’ve been studying what happens when, instead of taking a belief as something that is yes or no, you think about belief in terms of degrees of confidence,” Christensen explained. “If you think of belief in that way, there’s no set of ‘things you believe.’ There are just different strengths of belief or disbelief in various claims. So, the traditional idea that the things you believe must be logically consistent just doesn’t apply.” After receiving his B.A. in philosophy from Hampshire College in 1978 and his Ph.D. in philosophy from University of California–Los Angeles in 1987, Christensen began teaching at University of Vermont. During his 20 years at UVM, Christensen rose from assistant professor to full professor and twice served as the interim chair of the philosophy department. He is the author of one book, Putting Logic in its Place: Formal Constraints on Rational Belief (2004), and 18 articles including publications in Philosophical Review, The Journal of Philosophy, and Noûs. Christensen also delivers presentations at universities and various symposia across the country. Prior to his work in the field of epistemology, which generally studies knowledge and rational belief, Christensen was interested in the philosophy of science. He explored the relationship between hypotheses and evidence, asking what determines whether given evidence supports or refutes a given theory. He is currently working on questions about how self-doubt should play into the theory of ideal rationality. This year at Brown, Christensen will be doing something he’s never done before: combining his teaching with his research. “I’ve never taught anything having to do with my own research; it was always two different compartments for me,” he said. “That’s something I’m really looking forward to at Brown.” – Deborah Baum

Katherine Dunlop True in all cases: That is the high bar set by a mathematical proof. To demonstrate a proof, mathematicians must make logical arguments that show a statement is true – every single time. This process of moving from conjecture to certainty fascinates Katherine Dunlop, an assistant professor in the Department of Philosophy. “Philosophy is about arguments, and proofs are the best. They’re bulletproof,” Dunlop says. “Proofs are decisive and there is something striking about that. Few fields outside of mathematics – if any – can claim certainty.” Dunlop’s main academic interests are the history and philosophy of mathematics and the work of Immanuel Kant. The German philosopher’s ideas about mathematical thought, laid out in his Critique of Pure Reason, are sensational, Dunlop said. “Kant has this absolutely fascinating account of how we can have mathematical certainty,” she said. “His bold view was that physical space itself – say the circles and angles we study in geometry – is nothing other than a feature of perception.” Dunlop’s passion for numbers and logic began in high school math classes in Indiana and continued at Harvard University, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy and produced a thesis on mathematical set theory. Later, she earned her doctorate in philosophy at the University of California–Los Angeles. Her dissertation was titled Kant on the Reality of Mathematical Definitions. For the last two years, Dunlop has lectured as a fellow at Stanford University. Her lectures reveal her keen interest in the history of thought, with talks on British empiricism, the Rationalists, early analytic philosophy and language and certainty. Brown was an obvious choice for her first professorship, Dunlop said. The undergraduates are engaged and original. And after World War II, Brown created a Department of the History of Mathematics – the only such department in the country. This resulted in a rich vein of scholarship on the transmission of science from antiquity through the Middle Ages. This work produced excellent library holdings. Last summer, for example, Brown acquired the personal library of late professor David Pingree, which contains some 22,000 volumes on mathematics and science in the ancient world – a major boon for Dunlop’s research. Even thought that department disbanded in 2005, Dunlop said that reflecting on mathematics – how it is done and how it has changed – is always relevant. “We ought to know something about intellectual history and how ideas and concepts are passed down,” she said. “And mathematical proofs are instructive. We all need to know how to put arguments together.” – Wendy Y. Lawton

James Fitzgerald It was Brown’s search for a Sanskrit expert that brought James Fitzgerald to Brown. Now, as the Das Distinguished Professor of Classics, Fitzgerald will be a very busy man. One of Fitzgerald’s ongoing projects is the translation of about 25 percent of the Mahabharata, a gigantic, 2,000-year-old Indian epic. “It’s an epic text, three to four times as large as the Bible, which developed and grew larger and more complex over the course of time,” Fitzgerald says. “Sometime around the beginning of the Christian era, many philosophical and religious treatises were woven into or deposited into the text. So it’s not just an epic story of war, but it’s also kind of a large library of religious and philosophical instruction. They used the entertainment value of the war story as a vehicle to transmit religious and philosophical materials.” “Much that is in the Mahabharata became fundamental to all forms of the Hindu religion in the succeeding 2000 years.” Fitzgerald says. “It is one of the major masterpieces of world literature, comparable to the ancient Greek and Roman classics, to the Bible, to Shakespeare – many of the most important world literary contributions.” The more familiar Bhagavad Gita is actually a small piece located in almost the exact middle of the text. “In some ways,” Fitzgerald says, “the Bhagavad Gita is the one piece of religious writing that has had the biggest impact on the formation of Hindus over the course of the last 2,000 years, and in many ways it’s comparable to the effects that the New Testament has had on Christians – it’s that important and that fundamental.” He also strongly encourages people to read it. “It’s not just an exotic thing that only the adventurous should become familiar with. I’m hoping that if people have access to it, and they spend some time becoming familiar with it, it will enter into the cultural repertoire of the United States and Europe.” Fitzgerald intends his translation to help bring that about. “My standard is to translate the Sanskrit into English that communicates with modern readers of English but which is also faithful to the Sanskrit text by a fairly conservative standard” In addition to his work with the Mahabharata and teaching courses on other ancient Indian epics, Fitzgerald will teach the philosophies and ideas surrounding Yoga and his own new understanding of the practice. “I often called Yoga a regimen or a discipline of meditation, but now I see that using a word like meditation overemphasizes the mental aspect of Yoga too much.” – Amy Morton

Jorge Flores Jorge Flores was a student in his native Portugal in the 1980s, when he experienced a new freedom studying Portuguese history. “Until 1974, Portugal was under an authoritarian dictatorship, so scholars were classified as either following the regime or being against it,” Flores explained. “In the 1980s, when my generation began working in this field, it became far less politicized and much more neutral.” Specializing in the Portuguese expansion in Asia in the 16th and 17th centuries, Flores’s research focuses on the empire’s political, social and cultural history. “This is one of the richest periods in the history of Portugal,” Flores said. “The population was only 1.5 million people in early 16th century and I think it’s amazing how such a small country managed to establish an empire in different continents and how this interaction with other cultures was strong enough to transform Portugal and to transform Europe.” Flores earned his B.A. in history from the University of Lisbon, and received an M.A. and a Ph.D. in history of the discoveries and the Portuguese expansion from the New University of Lisbon. He served as lecturer at the University of Macau for five years and later taught at a number of Portuguese universities before spending two years as visiting assistant professor at Brown. He has published nine books, including edited volumes, and dozens of book chapters, journal articles, book reviews and shorter works, written both in Portuguese and English. Flores’s current research examines the Portuguese interaction with the north Indian Mughal Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries. He’s primarily interested in how political events and the daily management of this frontier relationship, mainly from Goa, impacted Portuguese and other European representations of the “Great Mughal.” With a joint appointment in the Department of Portuguese and Brazilian Studies and the Department of History, Flores will be teaching undergraduate courses on the history of the Portuguese overseas empire, European expansion in Asia, early modern Portugal, and ethnographical writing in early modern Portugal. – Deborah Baum

Ömür Harmansah Ömür Harmansah grew up in Turkey, moving every two years from one town to another because of his father’s work as an agricultural engineer. Perhaps it was all that exposure to various parts of Anatolia that helped to inspire Harmansah’s own work today. He loves looking at the architectural traditions of different regions, both ancient and modern. He is facinated by cities themselves, the intricacies of urban life, and how the culture of cities “shaped people’s social, private and domestic lives.” Harmansah adds on his Web site, “I ended up studying architecture in Middle East Technical University, Ankara, who knows why, stuck between a naive desire to become a poet and being good at math.” Today, Harmansah’s research interests center on the archaeology and material culture of the Ancient Near East, particularly Syria, Anatolia and Mesopotamia. He holds a Ph.D. in the history of art from the University of Pennsylvania, following a Master of Arts in the history of architecture and a Bachelor of Architecture from Middle East Technical University in Ankara, Turkey. Recently he contributed to the Mapping Augustan Rome project with a series of entries, published as a Journal of Roman Archaeology supplement. He participated in several archaeological field projects in Turkey and Greece, including Gordion, Ayanis, Kerkenes Dag and Isthmia. Harmansah points out that archaeologists “look at architecture, pottery, food remains, ancient texts and all kinds of artifacts in order to speculate about how the peoples of the past lived, thought and experienced the world.” He’s especially excited about a field technique called micromorphology, which uses even the tiniest remnants left in structures to learn “what people were eating, spilling, discarding, what pictures were on their walls, how often they repainted them ... When you excavate a city, you do not have only buildings – you have foods, texts, a rich range of material remains to reconstruct their lives.” Having had his first full-time teaching experience at Reed College in Portland, Ore., Harmansah came to Brown last year as a visiting assistant professor and now joins Brown as an assistant professor with a joint appointment to the Department of Egyptology and the Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World. – Molly de Ramel

Jacques Khalip Jacques Khalip is an intellectual omnivore, tackling Romantic poetry, queer theory, aesthetics, critical theory and sexuality studies with zest. What binds these seemingly disparate topics is identity – how we see ourselves, how we fit into the culture. “What is the self, and what it means to be in the world, is what essentially interests me,” Khalip said, “and Romanticism brings so many of these topics together – sexuality, beauty, politics, philosophy.” Khalip, an assistant professor in the Department of English, will teach British Romanticism to undergraduates this year. It’s his passion, one that goes back to adolescence. At 16, he read William Blake for the first time. He was hooked. “Blake is powerful – ferocious rhetoric, radical ideas, raw emotion,” he said. “I just read it and I felt at home. And all of us, I think, want to be transported when we read. Not in a Candy Land kind of way, but simply to be taken to a different world. Romanticism was what transported me. Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, Keats, Blake. They have this spooky majesty. They’re what I always come back to.” Khalip received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English from McGill University and earned his PhD in English at Duke. For three years, he taught in the Department of English and Cultural Studies at McMaster University. Throughout his academic career, Romantic poets pop up – in journal articles, essays, lectures. Stanford University Press will soon publish his first book, Anonymous Life: Romanticism and Dispossession, which examines the concept of Romantic anonymity as a way to resist the Enlightenment’s emphasis on transparency, self-disclosure, and emotional autonomy. Khalip, a native of Montreal, can’t wait to begin his work in Providence. Brown’s exceptional students, and its strong English department, were the draw. “My job talk at Brown was the best ever,” he said. “I’ve never had that kind of reception – so many strong questions. The faculty and the students were impressive. And you know, Brown is Brown. It sounds silly, but I remember thinking about it as a place to be even as an undergraduate at McGill. It’s this big Ivy League institution that is inclined toward the liberal arts. The English department is one of the best in the country. They give graduate students the attention they deserve. And I thought, ‘That’s the place I want to be.’ And now I will be there, pushing my teaching and research to the limit.” – Wendy Y. Lawton

Thomas Lewis Examining the nature of self and community and the significance of tradition, reason, and authority in religious, ethical and political thought, Thomas A. Lewis (Tal) has focused much of his scholarly work on the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. “Hegel wrote at a time when conceptions of religion, society, and politics were being dramatically reformulated,” Lewis said. “The outcomes of those shifts have profoundly shaped the modern West—particularly our preconceptions about how these spheres interrelate.” Lewis, the Vartan Gregorian Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, comes to Brown from Harvard University, where he served as assistant professor with a joint appointment on the Committee on the Study of Religion in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and the Divinity School. A member of Brown University’s Class of 1990, Lewis received his Ph.D. in religious studies from Stanford University in 1999 and spent time at the Freie Universität zu Berlin. He has taught at the University of Iowa, the University of California–Davis, Stanford, and at a K-12 school in Quito, Ecuador. He was also a visiting fellow at the Center for the Study of Religion at Princeton University. His publications include Freedom and Tradition in Hegel: Reconsidering Anthropology, Ethics, and Religion (2005), as well as numerous articles on the work of Hegel, Gustavo Gutiérrez, conceptions of community, and comparative ethics. Lewis is currently working on a new book, Religion, Modernity, and Politics in Hegel, which focuses on Hegel’s philosophy of religion and its relevance to contemporary discussions of religion and politics. “We lack adequate intellectual resources for talking and thinking about religion and its role in public life today,” Lewis said. “Hegel offers a proposal that cuts against both sides of our polarized contemporary debate. That makes him a valuable resource.” Mark Cladis, chair of religious studies, praised Lewis’ “genuine love for the vitality of the classroom” and says Lewis has already been active in helping the department revise its graduate and undergraduate curriculum. “Tal Lewis will bring to Brown multiple strengths as well as an indisputable track record of outstanding accomplishments in research, teaching, and university and professional service,” Cladis said. “He is a model of the dedicated teacher-scholar and University citizen.” Lewis is excited about the interdisciplinary opportunities that exist at Brown, specifically with colleagues in philosophy and political theory. Recalling his own undergraduate days, he’s also looking forward to the intellectual curiosity of Brown students. “Certainly, Brown’s pull is strong for me. I had an extraordinary experience here as a student and was deeply shaped by that time,” he said. “I feel many of the questions I had as an undergraduate are still the questions I’m pursuing now, though in different materials and with different tools.” – Deborah Baum

Aldo Mazzuchelli The essay sat for more than 100 years in the national library in Uruguay, noticed by scholars but never published. The work is a tart satire, aimed at exposing the repression of Spanish Catholicism at the turn of the 20th century, and written by an acclaimed poet, Julio Herrera y Reissig, an early proponent of modernism in Latin American literature. The satire was written in 1900 and for its day it was racy – sex and divorce were frequently mentioned. Herrera y Reissig also cut a shocking fin de siècle figure, publishing, for example, a photo of himself shooting up morphine in his bed. But the poet was poor and when excerpts appeared in magazines, the critics were harsh. So the satire remained tucked in the archives like treasure. Then Aldo Mazzucchelli recovered it. And, last year, he published it. His book, which includes all 580 pages of the satire, Tratado de la imbecilidad del pais por el sistema de Herbert Spencer, along with an introduction and a critical essay, sold out in four months. It is now in its second printing. A new assistant professor in the Department of Hispanic Studies, Mazzucchelli said the old essay sheds new light on Latin American at the time. “It is filled with details, intimate details, about the private lives of people on the continent at that time,” Mazzucchelli said. “It’s like an incredibly clear window into that world.” Mazzucchelli also said the essay is a strong example of the Modernismo movement of which Herrera y Reissig was a part. The movement included a group of poets from Latin America who began to publish in the late 1800s. Influenced by French writers such as Rimbaud and Verlaine, as well as American poets such as Poe and Whitman, this new wave of writers used often lyrical language to describe magical worlds filled with peacocks and princesses – symbols that contrast with the harshness of modern city life: factories and filth, crowds and unemployment. Modernismo, a main area of research interest for Mazzucchelli, was enormously influential. It was the first truly Latin American literary movement, one that went on to inspire writers such as Vicente Huidobro and César Vallejo. At Brown, Mazzucchelli will continue his research into Modernismo and his exploration of Herrera y Reissig’s satirical essay. A graduate of Stanford, Harvard and the Instituto Nacional de Dodencia in Uruguay, he will teach a survey course in Latin American literature and a seminar on tango and the culture of Modernismo. In his spare time, Mazzucchelli writes poems; he has published five volumes. He also plays guitar, flies planes and visits the 25 acres he and his sisters own near Punte del Este, which one travel writer dubbed “the Hamptons of South America.” The land is planted with 2,000 olive trees and offers a beautiful view of pastures that roll to the sea. – Wendy Y. Lawton

Kiri Miller On the surface, it appears ethnomusicologist Kiri Miller’s research interests are rather disparate. Her 2005 dissertation work focused on the American folk tradition of Sacred Harp singing, while her recent research explores the role of music in digital gaming, particularly in the notoriously violent Grand Theft Auto (GTA) series. “Yes, in some ways the topics seem very unrelated,” said Miller, assistant professor of music, “but I see an affinity. Both Sacred Harp singers and GTA players are dispersed communities oriented around mass-produced media – a tunebook and a videogame. And both groups use music to craft a sense of place.” Sacred Harp singing does not involve a harp. It is an unaccompanied choral tradition that draws together a far-flung community with roots in the American South and flourishing branches in New England, the Midwest, and on the West Coast. Singers gather for weekend conventions, where they divide into voice parts and make music for hours, selecting songs from a shape-note tunebook called The Sacred Harp. During her fieldwork, Miller participated in Sacred Harp conventions in 18 states. She found the gatherings to be a place for this politically and socially diverse group to celebrate pluralism and mutual tolerance. “Singing accomplishes something that speaking could probably never accomplish for this group – it creates a profound sense of belonging, loyalty and mutual responsibility. That doesn’t mean differences disappear, but it does help build a foundation for tolerance.” Miller got interested in music and digital gaming as she became increasingly aware that videogames were becoming a major medium for music distribution worldwide. In the Grand Theft Auto games, players have an unusual degree of control over the soundtrack to their criminal underworld exploits: They are free to move among 11 in-game “radio stations,” ranging from hip-hop to country to classic soul. Miller says the format gives players the opportunity “to control the gameplay experience by using music actively.” Additionally, her research looked at how designers create “musical canons” when selecting radio playlists that purport to represent particular genres. Miller’s fieldwork involved a Web-based qualitative survey, along with one-on-one interviews with GTA players. As with Sacred Harp singers, she investigated how this dispersed community of players communicates using listservs, message boards, and other online forums. She is now embarking on a similar project centered on the Guitar Hero games. “Given the polarized political atmosphere that we’re in, I believe people are using new technologies and both old and new traditions to build a sense of connection and community,” she said. Since receiving her Ph.D. from the Harvard University Music Department in 2005, Miller has been an Izaak Walton Killam Memorial Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Alberta, Canada. Her book Traveling Home: Sacred Harp Singing and American Pluralism is forthcoming this fall from the University of Illinois Press. In addition to teaching courses on musical youth cultures, diaspora, technoculture, and ethnographic method this year, Miller will be leading a for-credit Sacred Harp singing group. – Deborah Baum

Douglas Nickel Most everyone has had this experience. You remember something from your early childhood – a vacation, a birthday party, a family gathering. But is it really your memory conjuring up those details? Or are you maybe remembering an old photograph? This often-confusing relationship between memory and photography is one area that interests Douglas Nickel. Nickel joins the Department of History of Art and Architecture as the Andrea V. Rosenthal Professor of Modern Art. He comes to Brown from the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Ariz., considered the nation’s preeminent research archive, where he served as director since 2003. At the University of Arizona he was also associate professor of art history. Prior to that, Nickel was a photography curator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art for 10 years while teaching as an adjunct professor at Stanford University and University of California–Berkeley. He graduated from Cornell University in 1983 and received his Ph.D. in art history from Princeton University in 1995. Specializing in the history of photography and modern art, Nickel has focused much of his scholarly work on 19th-century British photography. His numerous exhibitions include Modern by Nature: Ansel Adams in the 1930s (2006); Dreaming in Pictures: The Photography of Lewis Carroll (2002); Carleton Watkins: The Art of Perception (1999) and Snapshots: The Photography of Everyday Life (1998). Nickel’s dozens of published books, reviews, and articles include Francis Frith in Egypt and Palestine: A Victorian Photographer Abroad (2003) and scholarly catalogues for the Watkins and Lewis Carroll exhibitions. Some of Nickel’s current work explores the role of the viewer in constructing photographic meaning. “There’s a not-always-rational response we have to photographs, a response that we don’t have to paintings and sculpture and other forms of art,” Nickel said. “It’s a reaction specific to the photograph. Something makes us confuse the image for reality, for the object itself, and what it represents. We don’t experience that confusion with any other form of representation. I think beliefs about the photograph’s veracity is what makes photography unique, gives it its rhetorical power, and ultimately makes it important historically.” Catherine Zerner, chair of the Department of History of Art and Architecture, expects Nickel’s teaching, “which embraces the entire history of photography from the earliest to the present day,” to enrich Brown’s offerings in 19th-century and modern art and connect to other areas of the University in new ways. “Douglas Nickel brings to Brown a stunning publication record together with experience as a professor, museum curator, and director,” she said. “This is especially welcome as Providence has long been a center of photography, and the collections here – at the Museum of Art, RISD, and others in the area – are exceptionally rich. We have waited long for this appointment and are looking forward to having a leading practitioner in such an important field.” – Deborah Baum

Michael Oklot Born in Poland and recently residing in Cairo, Michal Oklot is finally settling down and arriving in Providence, joining Brown as assistant professor of Slavic languages. The topics of many of his papers defy the lay intellect – “Possibility of Phantasmogoria with Hippopotamuses” or “Matter in Gombrowicz” – and challenge the traditional, as in “Sexual Life of Clones.” Attending the University of Warsaw, during the period of tumultuous change in the 1990s Oklot dove into politics, literature and sociology. He began one of the first independent public opinion research institutes in the country. One of his first clients was Lech Walesa and the Democratic Union party emerging from the Solidarity movement. Eventually his path led back toward academia. Oklot earned a master’s degree and then a Ph.D. in Slavic languages and literatures at Northwestern University. He has published articles on literature and literary theory in English, Russian and Polish. What intrigues Oklot about spirituality in Russian literature? “The struggle to embrace spiritual and material worlds in the artistic image ... and this is why one can say that the incarnation or life itself are protagonists in the novels of Russian great spiritual writers like Dostoevskii or Tolstoy.” Currently, Oklot is revising his dissertation – Phantasms of Matter in Gogol (and Gombrowicz) – into a book under contract from the Dalkey Archive Press. This fall, he will be teaching the Russian novel from Gogol to Nabokov and spirituality in Russian literature of the 20th and 21st centuries. Having an experience of starting and conducting summer programs in Poland for Northwestern University and teaching Polish and Eastern European culture at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, he hopes to develop an interest in Polish studies as well among Brown students as well. – Molly de Ramel

Ed Osborn Ed Osborn has ambitions for his sound installations: “The idea is to deprive time of its structural significance,” he says. Osborn’s sound art pieces take many forms: sculpture, radio, video, performance and public projects. His works, with titles ranging from Night-sea Music to Flying Machines to Blindfields, defy explanation. His Web site may say it best:

He hopes his works “are not about time, but about space” and the rewards of “how things get altered when you spend a long time with them, slow down, absorb, concentrate, and are rewarded.” Formal training for Osborn began not with art, but with instruments: French horn, jazz guitar, and the Javanese gamilon. He has performed, exhibited, lectured and held residencies throughout the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, New Zealand and South America. The recipient of many awards including a DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Stipendium and a Guggenheim Fellowship, he received his M.F.A. in electric media at Mills College and his music composition B.A. at Wesleyan. He joins the Department of Visual Art as an associate professor, focusing on sound-based media. – Molly de Ramel

Vanessa Ryan Vanessa Ryan is the type of humanist who happily talks about string theory, brain scans or imaginary numbers. She has spent the last few years learning about brain science – not the brain science of today, but Victorian physiological psychology. Specializing in 19th-century British literature, Ryan’s recent work traces the emergence and influence of this 19th-century mental science on Victorian fiction. As psychology materialized as a field, Ryan says its central ideas and terminology were absorbed into Victorian literature and culture, resulting in broad cultural impact. Using the writings of Wilkie Collins, George Eliot and Henry James, she examined how the authors used psychology to think through the mind/body problem and explain concepts of free will, memory and involuntary behavior in their novels. “I argue that Victorian writers found in physiological psychology new and more sophisticated models for casting human intention and behavior in the novel, as well as a new vocabulary with which to depict unconscious and altered states of mind,” Ryan explained. “I’m particularly interested in what was called at the time ‘unconscious cerebration.’” She is now working to turn this project, also the subject of her doctoral dissertation, into a book titled Thinking Without Thinking in the Victorian Novel. Ryan’s current project explores the alleged decline of the “public intellectual” by looking at a related crisis in the late 19-century and Edwardian period. “There’s been a slew of books recently on the death of the intellectual in contemporary culture,” Ryan said. “If there is such a fundamental shift happening, I want to find out from what are we changing? What is and has been the character and role of the intellectual?” By uncovering the historic origin and development of the concept, Ryan hopes her project will offer a “much needed pre-history” to the current debate. Most recently a junior fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows, Ryan received her Ph.D. at Yale University in 2004. She earned a B.A. in literature from Harvard and completed a Fulbright Fellowship at the University of Tübingen, Germany. Ryan has published articles on Thomas Carlyle, Arthur Hugh Clough, G. Bernard Shaw, and Edmund Burke in RES: Review of English Studies, Victorian Poetry, SHAW, The Journal of the History of Ideas, and Literature and Medicine. Kevin McLaughlin, chair of the Department of English, regards Ryan to be at the very top of the field of new scholarship on the relations between Victorian science and literature. “We are impressed with her knowledge of, and ability to teach, the whole range of Victorian prose – fiction and nonfiction,” McLaughlin said. “Ryan’s work on the novel enhances a traditional strength in this field in the Brown English department. Her work on literature and science adds an exciting and timely new dimension to the department’s offerings.” – Deborah Baum ###### | |||