This project details memories and memorials from Providence’s tragic legacy of hurricane disasters.

The images portray a phenomenon of unintentional marks made intentional monuments.

Throughout, glimpses of former catastrophe are countered with miniature acts of remembrance.

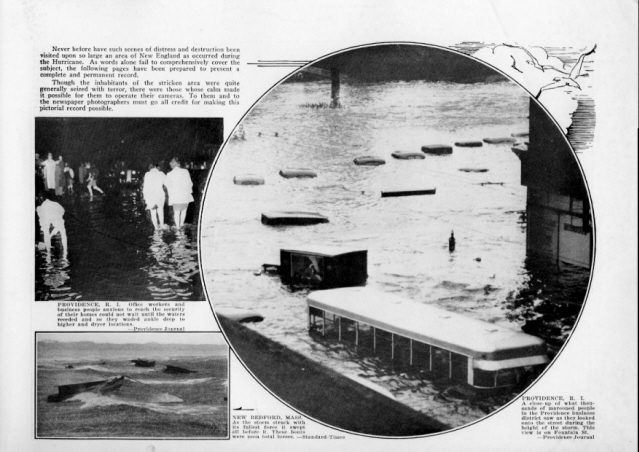

(Providence during the Great New England Hurricane of 1938)

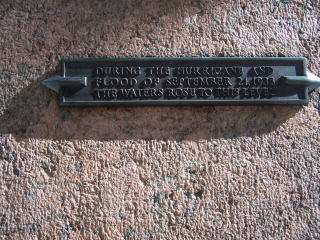

Walking through the old sections of downtown Providence one does not, in all likelihood, easily notice the occasional, often well-worn, plaques that adorn the exteriors of several impressive buildings. These small memorials trace the high-water marks attained during the city’s most devastating hurricanes. At the precise level to which a natural force once lifted to cause havoc and devastation, an urban community, still standing, commemorates its own resiliency. These buildings, as structure, as material, and as symbols, remain to serve as inscribed sites of survival.

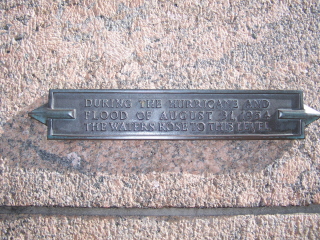

(Memorial plaques on what is now a RISD owned building at 15 Westminster St., and on the Banigan Building at 10 Weybossett St.)

As Americans we are, of late, all far too aware of the threat of hurricanes and natural disasters. Especially in the years since the disaster along the Gulf Coast, our news media and policy makers have increasingly worked to alert the entire country of impending peril, making every natural disaster into a national concern. Often, it seems, the collective American community experiences a shared sense of widespread anxiety when one of our great cities or regions is threatened by weather, fire, or earthquake.

As members of the Rhode Island community, though, I wonder how many of us are aware of the long and devastating history of natural disasters right here in our own city and state? Over a span of nearly two centuries, New England, Rhode Island, and especially the city of Providence, experienced weather patterns that created crippling floods, and, on several occasions, powerfully destructive hurricanes.

(Providence during Hurricane Carol in 1954)

Originally known as “gales,” hurricanes targeted Providence as early as the mid-18th century. The first was recorded to have swept ashore on October, 24th 1764. The storm was reported to have caused the highest tide in recorded memory, and destroyed everything in its corridor, including the famed Weybosset Bridge.

The Great Gale of 1815 raised a tide of 11 ft, 9 ½ inches above mean highwater. The storm swept across Rhode Island, destroying innumerable houses, barns, and nearly all the building wharves along the coastline. Reports indicated that every vessel in the harbor was propelled from its moorings. In downtown Providence, the bowsprit of the ship Ganges inflicted damage as high as the second story of the Washington Insurance Building. The storm dismantled the Second Baptist meeting house, though it only slightly damaged the still-standing First Baptist meeting located on higher ground.

The September Gale of 1869, newspapers reported, was nearly as bad as that of 1815, though less is known of its damages.

(Memorial Plaque on building at 15 Westminster St., though likely saved from another building at this site.)

The first gale of the twentieth century, dubbed the “Great New England Hurricane,” landed on September 21, 1938. This massive storm moved swiftly and powerfully up the Atlantic Coast, picking up force all the way, and eventually touching down on New York’s Long Island. But it certainly did not stop there. In fact, it saved its greatest devastation for New England, most especially for the Providence area. When damages from the storm were eventually tallied, estimates topped nearly 100 million dollars, an astonishing total for the time period. It is still considered perhaps the worst disaster in Rhode Island history. Some two hundred and sixty two people were killed across the state. Low-lying downtown Providence was the site of many particularly horrifying scenes. Nearly every building saw water up to its first story, and several people perished before even being able to escape their automobiles.

(Providence during Great New England Hurricane of 1938)

As the remarkable footage included below demonstrates, the ambitious forces of the Works Progress Administration sprung into action to help rescue and recover Rhode Island and greater New England. The clean-up took months, even with the thousands of government workers plunging in to help. As the narrator explains, the hurricane was considered all the more overwhelming because of its massive touchdown in the “thickly settled, highly developed New England.” Though its masculine and militaristic undertones are perhaps objectionable to contemporary sensibilities, the film contains extraordinarily affecting imagery, itself constitutive of an archival memorial to the tragedy of 1938.

[]

The most recent hurricane to land in Providence did so on August 31, 1954. Called “Carol”—as names were now being granted to the storms—the hurricane, with a tide 13 feet above mean high-water, wreaked havoc and inflicted enormous damages throughout the city and state. Nearly matching the total from 1938, the complete cost of the disaster was estimated at 90 million dollars. Now fully in the age of the automobile, some three thousand or more cars were washed-out and ruined. The storm’s death toll reached nineteen.

(Newspaper headline reporting Hurricane Carol; Memorial plaque at the Banigan Building, 60 Dorian St.)

In 1960, local, state, and federal policy makes decided that the time had come to take unprecedented preventative measures to combate future hurricanes. The commenced construction of what would become the Fox Point Hurricane Barrier, a massive, first of its kind structure spanning the Providence River designed to control the rising tide waters, storm surges, and floods experienced during previous hurricanes. The barrier, completed in 1966, includes five principal sections: river gates, rock and earthen dikes at each shore, vehicular gates at each shore where roads pass through the dikes, canal gates at the west end of the barrier used to service the adjacent electric power station, and a pumping station to control the flow of water.

The barrier has been used successfully on two occasions. The first, in 1985, to hold back two feet of rising water created by Hurricane Gloria. Then again, in 1992, to prevent the likelihood of serious damages from Hurricane Bob. As an unintended consequence, it has also served to keep the river level higher during low tides for the during the summertime WaterFire events.

Today hurricanes are but a minor threat to Providence, its buildings, and its people. But on several tragic occasions, over a long period of the city’s history, this was not the case. Like many American urban centers, Providence’s downtown has seen its ups and downs, its boom times and its slumps. Today there is sustained interest in reviving the downtown area and returning it the former stature still suggested by many of its finest structures. As the city and its residents look toward a brighter, revived future, it is perhaps evermore important to recall the instructive traces from the past, many of which are left for us on the material structures of our everyday life. These small high-water memorials, as site-specific, once unintentional marks made permanent monuments, offer a powerful message of endurance and resolve.