Agency, Orientalism and the Assyrians

September 19, 2011

The idea behind the design of this particular week was to look at the beginnings of Assyriology and archaeology of the Assyrian Empire, and attempt to relate it to the foundations of the discipline, especially the field of Near Eastern Studies, including philology, archaeology, art history and material culture studies. The historical and geo-political context of European and American colonialism/imperialism into which Near Eastern archaeology was born, has obviously impacted fundamentally how it conditioned and structured its knowledge-producing practices during the infancy of the discipline (Bahrani 1998). The fact that the earliest steps of this process coincides with the excavation of Assyrian palaces and the mass-shipment of their wall reliefs to European and American Museums is noteworthy for the goals of this seminar- locating our filed in the harsh and heated world of nationalism and modernity. Each discipline develops its own peculiar scholarly practices, methodologies, interpretative theories, discursive tools and ideologies in specific circumstances and it is always healthy to think through them every now and then.

One of the interesting developments in Near Eastern Studies in the recent years is the production of detailed historical studies of the emergence of the discipline- stories told in minute historical details of diplomacy, local politics, colonial administration, evangelical missions, traveler-antiquarians, map-making, and archaeology combined with secret military, political or religious, or museological agendas (e.g. Cohen and Kangas 2011, Diaz-Andreu 2007, Holloway 2006, Goode 2007). The image that emerges from these accounts is an impressively complex world of cultural practices, political negotiations, material interests and social imagination. In the past, such studies have always been written from the perspective of the western archaeologists and museums, and portrayed archaeologists as scientists in the field whose work is continuously made difficult by stubborn local officials and bureaucrats, government offices who are reluctant to issue work permits and permits to take away excavated materials, or ignorant locals who are completely unaware of the historical treasures of their environment. However recent studies of the history of archaeology in the region now present a much more balanced view of archaeological and museological practices, placing emphasis on influential figures such as Osman Hamdi Bey in Ottoman Turkey, Sati’ al Husri in Iraq, and Rifaa Rafii al-Tahtawi in Egypt (see e.g. Colla 2007, and the University of Pennsylvania exhibition and symposium Archaeologists and Travelers in Ottoman Lands).

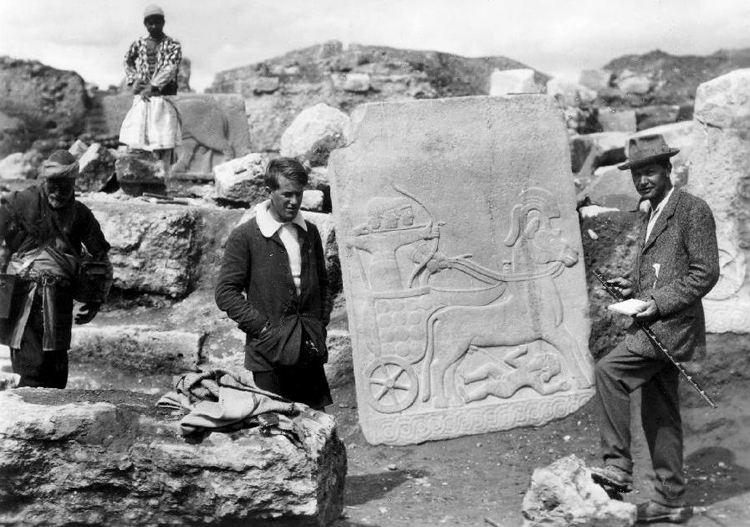

Woolley and Lawrence of Arabia at Karkamish (1913) Liddell Hart Collection for Military Archives, King's College London.

Woolley and Lawrence of Arabia at Karkamish (1913) Liddell Hart Collection for Military Archives, King's College London.

The question that needs to posed here is perhaps: how could a critical reading of the early history of Near Eastern archaeology contribute to the postcolonial studies of 19th century western engagements with the Middle East, especially when considered within the context of emergent colonial modernities and the politically slippery world of nation-state formation. In my view there is a great potential here, not only to the benefit of the discipline's own genealogy and private history, but also good for thinking through the childhood of humanities and social sciences. Those archaeological practices that were first tried on Assyrian palaces in the Middle East or the welcoming of the Assyrian reliefs to western museums are not simply uninformed pre-disciplinary and casual engagements with the past, but precisely constitute the foundations of our current academic endeavors today. And I think this is a good moment to understand this peculiar history of archaeology as a field science, as part of the cultural history of the local and European interest in the distant past. Needed is a balanced use of local and European archives, literary corpus of the time period, visual documents and architectural heritage, and such resources. It is critical to understand these processes from the perspective of local and international politics, practices of representation, and the institutionalization of the modern nation states and colonial empires, as Elliot Colla has brilliantly done in Conflicted Antiquities (2007). Taking the lead from the traveling sculptures and tracing their cultural biography and their tumultuous social life might be the answer.

References

- Bahrani, Zainab; 1998. “Conjuring Mesopotamia: imaginative geography and a world past,” in Archaeology under fire: Nationalism, politics and heritage in the Eastern Mediteranean and Middle East. L. Meskell (ed.), Routledge: London and New York, 159-174.

- Bohrer, Frederick N.; 1998.“Inventing Assyria: Exoticism and Reception in Nineteenth-Century England and France,” Art Bulletin 80: 336-356.

- Cohen, Ada and Steven E. Kangas (eds); 2010. Assyrian reliefs from the palace of Ashurnasirpal II: a cultural biography. Hanover: Hood Museum of Art and University Press of New England.

- Colla, Elliott; 2007. Conflicted Antiquities: Egyptology, Egyptomania, Egyptian Modernity. Duke University Press.

- Diaz-Andreu,Margarita; 2007. A World History of Nineteenth-Century Archaeology: Nationalism, Colonialism, and the Past.Oxford University Press.

- Frahm, Eckart; 2006.“Images of Assyria in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-century western scholarship.”In Orientalism, Assyriology and the Bible.S.W.Holloway (ed). Sheffield Phoenix Press, 74-94.

- Holloway, Steven W.; 2004.“Nineveh Sails for the New World: Assyria Envisioned by Nineteenth-Century America” Iraq 66: 243-256.

- Holloway, Steven W. (ed); 2006. Orientalism, Assyriology and the Bible.S.W.Holloway (ed). Sheffield Phoenix Press.

- Larsen, Morgens Trolle; 1996. The conquest of Assyria: excavations in an antique land 1840-1860. London and New York: Routledge.