The Landscape of the Subconscious: "Drinking from Place"

Here is the ocean. The place where land meets sky and water pulls and calls as surely as Odysseus’ sirens. What is it that has drawn man to its edge for generations? Perhaps it is the reassuring promise of sustenance and life, or the strength of the swing of tides, steady as the path of a pendulum. Yet the ocean is a fickle child, at times hunching clouds onto the shoulders of its horizon and heaving squalls of tantrums at the unwary and unprepared. It both connects and isolates as one stands on the shore and thinks what may be below the curve, where the world sidles away and drops, where the eye is met by such vast space that contains so little. It is a place of possibility. People have chosen to make their homes at the edges of the oceans for thousands of years; the reasons for living by the sea have evolved just as our interaction with the landscape has changed. I can only speak for my own experience, for, as anthropologist Keith Basso points out, “the self-conscious experience of place is inevitably a product and expression of the self whose experience it is.” (Basso, 55) In the culture of my upbringing, the world of my childhood was a very small town by the edge of the sea. Now, water is no longer the easiest or safest means of travel, but the ocean is still coveted where I come from (just look at property tax if you need convincing). Here, a living of sorts can still be made from the sea; the economy of our town is based on the summer seaside tourist trade. Over the past three hundred years, we have hemmed the coastline with our railways and built up the edges with our docks and tamed the beaches with our hot dog stands. So, each summer when the herds of tourists migrate to my town, I make my own pilgrimage. I travel to another place that is between the land and the sea, where the human interaction with the landscape is far less tangible than the beach umbrellas, the begging seagulls, and the gritty hot dogs of my town.

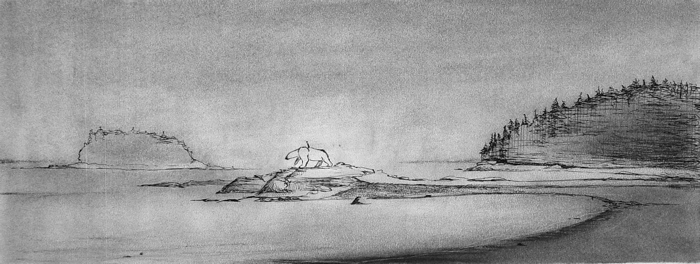

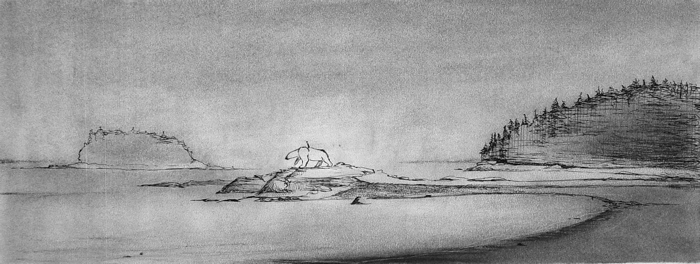

The place that I return to each summer is a small section of relatively wild coastline in Maine called Eggemoggin Reach, just south of Mount Desert Island. Here, docks submit to the will of tides that gobble thirty feet of rock and seaweed and barnacle beach with each rise and fall, and buildings on the mainland nestle and hide behind the trees. The Reach is peppered with tiny islands, and the only human construction imposed upon them consists of names on a nautical chart. My return each summer has become a ritual; it is my time to reflect and ready myself to begin a new year. I have tied associations of openings and closings to this place because I am often here at a natural pause in my life, between work and school, summer and fall. The very fact that the Reach is a boundary, the place in between the ocean and the land, suits this type of contemplation very well. Yet I only ever spend a few days, perhaps two weeks together at most, in this place. What wisdom can be gained from a place in such a short amount of time? To determine this, one must examine the methods by which we absorb, internalize, and “drink” from place in order to gain depth in our relationship with a specific landscape. And once we have identified how we drink from place, we should also examine why we drink from place.

Eggemoggin Reach is fundamentally very unlike the landscapes of our readings in that one cannot actually walk across this place. Though this is a very basic logistical problem, our chosen manner of passing through this space becomes fundamental to our understanding of the landscape. I can neither walk nor safely swim here. Instead, I approach the Reach from a very personal and perhaps somewhat unusual vantage point; that is, from the thwarts of a very small wooden dory. Each summer, I join a fleet of fifty or so wooden boats between seventeen and twenty feet long for just a few days. Each group of people on this strange pilgrimage has painstakingly snailed their way to this bit of rocky coastline, carrying their belongings in the beds of pickups and the hulls of their temporarily wheeled and land-bound boats. During this incredible week, we hem the Reach with the wake of our tacking, and this is the only sign we leave of our passing. As soon as the wind wears away the evidence of our travel, no one would ever know that we came through on sail and oar. We pass through this space quietly in our faithful, un-mechanized little vessels. At the fastest, we make five or six knots, or about seven to eight miles an hour. We balance between water and air, current and wind, and must keep constant watch for rocks and sandy shoals. The boats allow us to pass through this landscape in a way that humans could not accomplish alone. For these moments, the fleet of craft propelled by the wind becomes a fundamental aspect of the landscape itself. We are pushed by the whim of this place, by the currents of the tides and the directions of the wind, and we must conform to the natural motion of the place. A sailboat interacts at all times with land, air, and water. In this sense, it is the perfect vessel to carry us to and through the places in between. We move at a pace no faster than a walk, and are free to absorb the landscape with all senses on high alert. Moving down close to the water on a long day provides me with my first long draught of the Reach.

In this first level of interaction, the act of passing through provides me with very concrete and even primal sensory impressions of the landscape. I hoard and squirrel these memories away to access when I am no longer in this space. These are sharp memories of skin tightened over bones by sunburn and salt, of the pervasive cold damp of the air above the water, of the rush of pushing liquid aside, of the purring of the rigging, and of the smell that is so particular to the places where land meets sea. But after the first long day of sailing, I begin to push past these initial physical interactions and reactions in order to store memories more deeply than simply in the nerves that lie just under my skin.

It is on the second or third day of traveling across the reach accompanied by the fleet and exploring the islands that I have absorbed enough of the place to begin processing it in less tangible ways. Now, I begin to take photographs and to draw, to write and to store fodder for memories. These photographs, drawings and essays will later become points of entry for me. They will become triggers for memory, symbols that will conjure my impression of this landscape as a whole as I have built it up in my mind over the past decade. The photographs and drawings and essays assist the translation of Eggomoggin Reach in my mind from a landscape that I exist within to a place that exists only in my imagination when I physically leave it behind. I take these symbols and paste them to my walls in my dorm room to create windows to this place when I am in need of a retreat. Translated into my mind, the Reach has become the landscape of my subconscious. And it manifests itself more than I had realized, and often, in unexpected ways. These manifestations are sips of a landscape that have been sieved through three levels of filters in my mind; first, I experienced the landscape in a purely physical manner as I passed through it. Then, I visually processed the landscape by converting it into a reproduction in the form of a visual image (either a photograph or a drawing). Finally, I have taken these images and translated them into written descriptions of the place that will aid me in sharing my personal interpretation of the landscape with people who have never been there themselves. This, I have done consciously and knowingly. However, I did not realize until about a year ago the extent to which I draw subconsciously upon this landscape and display this in facets of my life that are totally unrelated to either my cultural heritage as the daughter of shipwrights and fishermen or to my relationship with the water’s edge.

Of the various places where my idea of Eggemoggin Reach pervades my life unexpectedly, this landscape ghosts most frequently and unintentionally into my artwork. This was not something I was even conscious of until last fall; in the process of retelling and illustrating a Nordic folk tale from my childhood for a class, I came to the abrupt realization that very few images from my imagination are purely constructs of my mind. I drew the first illustration and thought little of it upon completion. However, when I picked it up again a few hours later to show a friend, I was suddenly quite shocked to realize that the vista I had depicted was not a place out of my “imagination” at all; rather, it was very clearly a representation of what the Reach is to me. The friend who was looking at the illustration with me even commented shortly thereafter that it resembled some combination of the photos on my wall (which were, of course, the previous summer’s takings). That moment led me to reflexively regard and re-examine any artwork from the past few years that I had created without specific assignment. And there, again and again, were doodles and drawings and prints and paintings of the Reach. My own interpretation of this landscape includes the boats; I feel that these are specific to this place in my mind. Though there is only a fleet such as this on the Reach for two weeks out of the summer, I have only ever encountered this landscape during those two weeks. Therefore, though these boats are not necessarily an indigenous or constant part of the environment, they are an integral part of my interaction with the environment. In this way, my interpretation of Eggemoggin Reach is entirely unique. My own perceptions and experiences in the actual place and my social and cultural background have colored my idea of this place; as a result, Eggemoggin Reach as I know it may not physically exist in reality. But at the same time, everyone’s Reach will be slightly different, from the people who have lived there all their lives to the people who have only experienced the place four times removed through my drawings and writing.

I have been drinking from the landscape of Eggemoggin Reach for about ten years. Each time I go back, my understanding of the Reach deepens. However, this is not a process that will ever be complete; one’s perception of dwelling has a boundless capacity to increase. Though I spend relatively little time on that small stretch of coast in Maine, I dwell within this landscape in a way that I do not anywhere else in my life. I dwell in it so richly when I am physically there that it nourishes my mind in an intangible way for the rest of the year when I am away from it. It has become a sort of anchor for me, and my view of this place as seen through the colored filters of memory, photographs, drawings, and pieces of writing changes constantly. It changes each time I physically return to the Reach, just as it changes with every doodle I draw that represents the place to me. Dwelling, or the process of interacting with one’s landscape, is as necessary to humanity as breathing. It is impossible to live in a vacuum, but it is possible to ghost through life without ever drinking deeply from place. At times, especially when I am at school, I am working in such an intangible world (that of theoretical papers and internet, of cell phones and online course reserves) that I forget what it is like to root myself in a place in a very physical sense, and to take in the landscape from that very basic vantage point. And this is why I continue to visit to the Reach, and to breathe more deeply the landscape each time I return.

Evelyn Ansel