The Automatic Turk: materiality, agency, performance, biography

Omur Harmansah

A response to Discussion Week 2: Materiality: ethnographies of material culture

Posted: February 7, 2007 Wednesday 11:08 pm.

Work In progress!

"Perhaps no exhibition of the kind has ever elicited so general attention as the Chess-Player of Maelzel. Wherever seen it has been an object of intense curiosity to all persons who think. Yet the question of its modus operandi is still undetermined... the Automaton a pure machine unconnected with human agency in its movements, and consequently, beyond all comparison, the most astonishing of the inventions of mankind."

Edgar Allen Poe, "Maelzel's Chess Player" (1836)

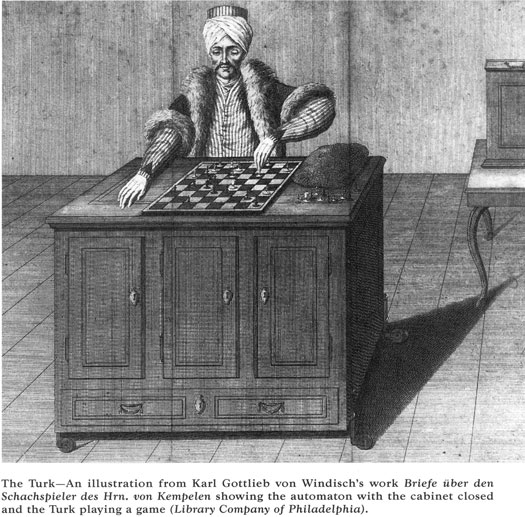

The 18th century chess-playing automaton, commonly known as "The Turk", built by the miraculous Hungarian Baron Wolfgang von Kempelen in 1769 to impress the Empress Maria Theresa is one of the most curious "living dolls" ever created. This is not simply because the Turk played chess so well that he was able to defeat pretty much all of his opponents during his grand tour of the world without revealing his secret and with spectacular performances. I am not even going to exaggurate the amusing claim of the automaton over the dearest features of our beloved human subjectivities: sharp reasoning, elegantly performing bodies and ability to speak (The Turk was capable of saying 'echec' at appropriate moments in the game). What is particularly fascinating about this automaton, this "android", is his complex cultural biography with which so many human lives, objects, and spaces became entangled over the years until it was finally burnt in a museum in Philadelphia (of all places) in 1854. Over the course of his 85-years of exhausting chess-carreer, The Turk met Edgar Allen Poe in Richmond Virginia in mid-1830s (Lewitt 2000: 226), defeated Napoleon Bonaparte in 1809 in Schonburnn (Standage 2002: 105) and Benjamin Franklin in 1783 in Paris. Charles Schmidt, a chess-player who hid in the Turk operating the machine, accused the Turk for "ruining his life" (Knappett 2005: 28). Several biographies of the Turk have been published (most recently Levitt 2000 and Standage 2002).

My interest in the Automatic Turk really started with its Orientalism. According to the available biographies of the contraption, its maker, von Kempelen never named it as "The Turk" but it acquired this name due to its elaborate costume, supposedly that of an "Oriental sorcerer" (while in the available illustrations, he looks more like an Ottoman courtier to me). Let's remember that the automaton was presented to the Hungaro-Austrian empress, who was known with her anti-Turk politics, and that the memory of the Ottoman sieges over Vienna in 1529 and 1683 were quite fresh. The Turkish image of the chess-player, its representationality was therefore not an uncomplicated issue. More on this in next week's paper.

The story of the Turk then is rich in arguing for issues of materiality, agency, performance and biography. The material presence of the Turk in various settings, enhanced with an eerie aura of a moving, living, reasoning doll, and its representational complexity in its Oriental persona, was first of all constituting the source of its social power. The maker of the automaton went into great pains in proving that there was noone hiding in the mechanism during the performances, and for years and years, noone could really figure out how it really worked. Alfred Gell refers to this aura "the enchantment of technology", or "the spectacle of unimaginable virtuosity." Similar thing when we are overwhelmed with the spectacularity of stone carving technologies at Egyptian pyramids. At times, even when von Kempelen tried to hide the machine from frequent public appearances, the Turk quickly became famous. If agency is defined as "the socio-culturally mediated capacity to act" then the Turk was able to take over its own biography, impacting large groups of people across the world. With its performances, its material existence, the automaton was an undeniably heterogenous phenomenon, where human intentionality, magical power of the Oriental other, chess as a political game of the kings, social performance in the public sphere were all gathered, overlapped, woven together.

Bibliography

Knappett, Carl; 2005. “Animacy, agency and personhood,” in Thinking through material culture: an interdisciplinary perspective. Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press, 11-34.

Levitt, Gerald M. 2000. The Turk, Chess Automaton. Jefferson NC: Mcfarland & Company Inc Publishers. John Hay Library-on reserve. (The scanned images below are from this book).

Standage, Tom; 2002. The Turk: The life and tiimes of the famous Eighteenth-Century chess playing machine. New York: Berkley Books.

Wood, Gaby; 2002. Living dolls: a magical history of the quest for mechanical life. London: Faber and Faber.

Other Response Papers of the Week | Response Papers Main Page | Course page