Saving Providence: Providence River Relocation Project and its Healing Impacts on Providence

Stories and beliefs in river deities and sacred atmosphere of the river that continue through myth and history demonstrate the importance of river in powerful cities and countries. River becomes a great resource in numerous ways thus have always been major factor in founding a new country or city. Rivers are the resource of rich soil, healthy clean environment, and water resource and become pathways to connection to the outside world. It can be said that the rivers of Providence nurtured and grew Providence in its beginning in the 19th century rivers have become a major part in development and during the industrial revolution.

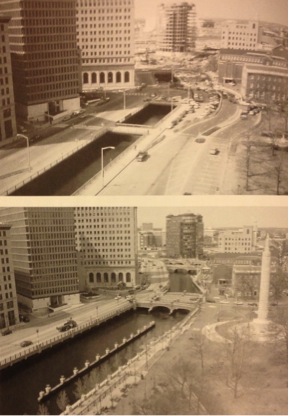

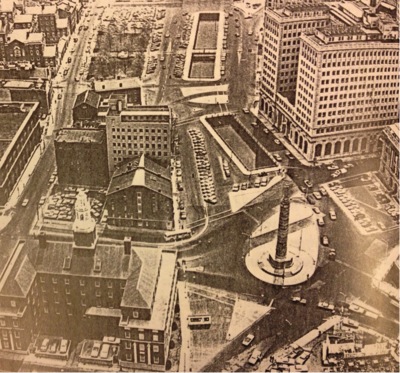

The Providence river relocation project, which lasted from 1986 to 1996, was a major city-revitalizing project to “reestablish a relationship between Providence and its long-abandoned rivers.” The main execution was reclaiming the Moshassuck, Woonasquatucket, and Providence Rivers, the removal of the “world’s widest bridge” over the Providence River, the creation of WaterPlace park and the establishment of riverwalks, and continuation of Memorial Boulevard (and) “Suicide Circle”.

Rivers of Providence

Rivers in Providence were the central cornerstone to renaissance planning in Providence. In the early twentieth century the Moshassuck and Woonasquatucket rivers were vital part of a vibrant Providence. Woonasquatucket River was an open route for Providence to trade and connect to Boston and other larger cities. In 1828, the opening of the Blackstone Canal on Woonasquatucket River, one of the American Heritage River, “between Providence and … Massachusetts (allowed the trade of) raw materials and manufactured products. This was the beginning a rapid process of industrialization along its banks. Woonasquatucket River and Moshassuck River were always a source that triggered the development of Providence. During the1900s was the River Relocation Project where an alteration in river has provided Providence with much potential of growing. Water was not only a way to reach the outside but also a fuel and energy in the Industrial revolution period. Thanks to the waterways provided by the rivers “Providence became the most industrialized city in the U.S. in the beginning of the 20th Century,” After the industrial revolution ended, the rivers were used to dump chemicals and waste from factories and mills; ever since the economy of Providence declined throughout the later half of the 1900s the rivers had been … neglected for decades. With the population increase and vehicles increased the rivers were covered by the Crawford Street Bridge, which, in the 1980s, Guinness Book of World Records listed as the widest bridge in the world. More than fifty to seventy percent of the polluted rivers was obscured with roadways and parking lots, which were only left “to function, at best, as storm sewers.” Nevertheless, the problem of traffic due to increasing vehicles and unsuitable flow left unsolved traffic problems in Providence throughout the decades. Through the new Providence river relocation project rivers revived and granted Providence major development, the Providence Renaissance, as the Providence river relocation project executed.

Traffic

The Crawford Bridge obscuring the entire river may have been a solution to unhygienic and aesthetic environment, yet the congestion in downtown Providence was still a critical problem to solve. The notorious traffic congestion at the Memorial Square, which was better known as the “Suicide Circle,” was a challenge to the drivers of Providence. (108) Because of the poor vehicle circulation “pedestrians …walked at their own risk anywhere near the Crawford Street Bridge and Memorial Square;” it is no surprise that the circle drive was called a “Suicide Circle.”

Sandwiching the “Suicide Circle”, the east side and downtown were completely disconnected; travel between the two sides of Providence was impossible. Downtown Providence was “dead,” no major building had been built since 1928, hotels and the last cinema and department store closed.

In solution to the dead downtown, the elimination of Suicide Circle and the relocation of the World War I memorial resulted the road to turn into a much simpler route, which significantly reduced the congestion. With the Crawford Street Bridge gone and numerous smaller pedestrian bridges formed, access to the other side of the river was easier for the people and motorists, eventually resulting to successful revitalization of the downtown.

Reconnecting to Historical Sites

Having nearly 400 years of history since its founding, Providence is one of the oldest cities in America and “the only major city that has placed its entire downtown on the National Register of Historic Places.” Embracing many of its historic sites in and around its area, downtown Providence was disconnected to the other major parts of the city such as the east side, College Hill, and the capital Center. The historical sites have been abandoned and forgotten, but demolishing of the “Suicide Circle” and enhancement of motor and pedestrian access to the historic area downtown, a substantial number of historic sites of Providence that were once extensively disconnected is now reconnected and back on the surface. Addition of riverwalks and multiple bridges along the relocated river restored historical links in Providence. The river relocation project revitalized and reaffirmed the value of the historical sites and the history of Providence. The river relocation project protected and enhanced valuable historical resources, without demolishing existing buildings in the downtown. The Decision to relocate the river than to demolish the historical sites and buildings reveals Providence’s choice to by keeping the water revealed and demolishing what covered the water was a way to heal, protect and secure the historical valuable. Undeveloped and forgotten places in downtown Providence were now revitalized. One of the goals of Providence river relocation, “(to) create an ordered sense of public spaces in a high-density, and to re-connect the College Hill and downtown historical districts” came to success. What was once dead and immobile has risen and become alive.

Providence has (holds critical preservation ethic) based on a firm belief that they should “save what we can.” With this ethic Water Place Park was created in order to acknowledge a "historic Providence" …(that) constitutes a historic pastiche of Providence, a "memory piece." Providence regains its importance in its historical value. Healing Providence in its identity as a one of the oldest and historic city in the U.S. Afterall, it was all Providence’s “strong preservation ethic (that) drove much of the River Relocation Project”

Parks and Waterfire

The river relocation project increased “tourism activities by providing ...gathering and resting places.” Along the rivers “numerous pedestrian access points … link the park to surrounding developed and undeveloped spaces.” Waterplace Park became provided opportunity for people’s gathering and relaxation. WaterFire, which Providence Journal columnist Bob Kerr refers to as “the only tribal rite performed by an entire state,” was developed and became a festival where all people of Providence come together to enjoy their time and bringing ”people back in downtown Providence." Just as Urban Age magazine noted on its Winter 1999 publish, “WaterFire was crucial in bringing people to the downtown waterfront ...filling the beautiful but previously empty spaces with people.” WaterFire proved to be Providence’s success “in bringing people back into the downtown and creating a cultural event that is unique to Providence“ which became its identity. WaterFire and Waterplace Park created opportunity for inspiration, rest, entertainment, gathering, and healing in Providence. Through the new use of river as a site of celebration, festival, art, performance, and attraction, the Providence river has exceeded its being; rather than just a way water run through, but a more crucial place to Providence’s history and development.

Conclusion

With the success of Providence river relocation project, streets were reorganized and realigned, downtown was accessible, eventually leading to reconnecting and protection of historic sites. Revitalization of the city happened through development its culture and arts around the river. The impact of the Providence river relocation project had Providence Renaissance come true. The quality of life and efficiency and safety in traffics and access to downtown and historic district and the cultural growth has become the most drastic in Providence.

The rivers in Providence, of what we can describe revived, has recreated the entire city; the rivers of Providence is indeed the rivers of providence. Roger William’s hope to find freedom in Religion has grown to become a “Renaissance City,” and of which the American Heritage River becomes the reason, a solution and the backbone of Providence’s rise during the Industrial Revolution period and the renaissance of the late 20th century. Whether it is a de ja vu, a coincidence, “the great irony of the Providence Renaissance that … (a) long-since-forgotten economic engines of Providence, have become so vitally important to the hopes of Providence--a "back to the future "theme,” or a simply natural outcome and a matter of river’s healing power, it comes down to a conclusion of which “the Providence Preservation Society puts … this way: the city's renaissance has "rediscovered the rivers that flow through the city center and exploits them to glue the city back together." Ultimately, the impact of the Providence river relocation project sums up to the fundamental following: As the river revived the city did as well.

Courtesy of Rhode Island Department of Transportation and Thomas Payne, WaterFire Providence

“Suicide Circle”

Courtesy of Rhode Island Department of Transportation

References:

Leazes, Motte; 2004. Providence: The Renaissance City. Dexter: Northeastern University Press: 71, 104, 105, 107, 130, 132, 137

Marshall, Philip. "Railroads and Rivers ." Phillip C. Marshall. Phillip C. Marshall, 01 Oct 2012. Web. 1 Oct 2012.

. "Providence River Relocation." Rudy Bruner Award. Rudy Bruner Award, n.d. Web. 1 Oct 2012. <http://www.brunerfoundation.org/rba/index.php?page=2003/river>.

. "Providence River Relocation: 2003 Rudy Bruner Award for Urban Excellence." Rudy Bruner Awards. Bruner Foundation, n.d. Web. 1 Oct 2012.