Posted at Nov 30/2012 12:13PM:

Alexandra Salinas Places of Healing Ömür Harmanşah Fall 2012

A Liminal State of Mind

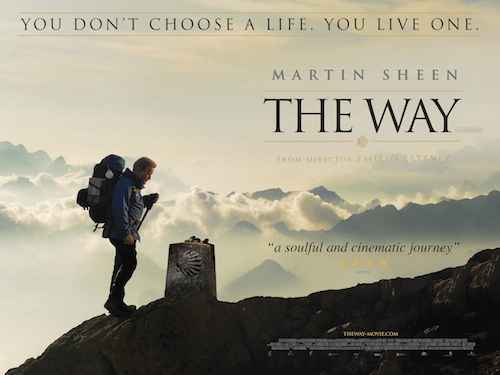

“We don't think about pilgrimage in this country. We don't think about meditation. The idea of taking a six-week walk is totally foreign to most Americans. But it's probably exactly what we need.” ~Emilio Estevez, regarding his father’s role in “The Way”

Pilgrimage, by definition, is a journey that one takes in order to pursue some form of moral or spiritual significance. Quite often, the final destination of a pilgrimage represents that person’s faiths or beliefs (Juergensmeyer, 2011). Whether it is a shrine or a church or a garden or even a completely barren land, that particular location, the pilgrim chooses, is a source of many powerfully redeeming forces. The notion of pilgrimage gained true prominence when the major religions began to emerge; Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (Tomasi, 2002).

When considering liminality, a rite of passage is often considered an analogous experience (Turner, 1977). A liminal phase, or a rite of passage, consists of three crucial phases: separation, margin, and aggregation. The first phase of separation is defined by a person’s complete detachment from their former state of being. Whether this detachment is triggered by the loss of a loved one or some other substantial event in one’s life, this separation marks the beginning, of what some consider, the healing process. The margin phase, also referred to as the liminal period, is characterized by this detached person entering a fog-like state of being. Actions, emotions, a person’s entire state of mind and self, are seemingly ambiguous and arbitrary at this stage. The phrase “stuck in limbo” comes to play here, in the sense that the person has to decide whether to sink or swim, whether to break through the fog or get lost in it. The final phase of aggregation is the light at the end of the tunnel. If this final stage is reached, the passage has been completed, and the person returns with a new sense of self, to a new stable life.

Those within the liminal phase are referred to as liminal personae, meaning “threshold people.” As mentioned before they are caught in a fog, and this fog “is likened to death” (Turner, 1977). As dismal as that sounds, one must remember the liminal phase is only meant to be part of the journey, and aggregation is on the horizon. Keeping this in mind, if the fog is like death, there is an implied rebirth in aggregation. This coveted sense of rebirth is the driving factor leading people out of the fog; it is the ultimate state of healing.

Arnold Van Gennep was a French folklorist and ethnographer. It is said, that he was ahead of his time in terms of his literature describing the transitions that define the human condition (Turner and Edith, 1978). He firmly believed that liminality could be applied to all phases of decisive cultural and social change, specifically the “historical quest for salvation and renewal” (Turner and Edith, 1978).

Within the Christian faith, a central theme is that of death and rebirth. Christianity is also comprised of liminal phases, or rites of passage, such as Baptism, First Communion, Reconciliation, Confirmation, Marriage, and Funerary Ritual. It is not by coincidence that the very first rite of passage is considered one’s birth into the faith and the final one’s death. Within the first and last passages, are series of rebirths, and with each rebirth one’s faith is renewed and reaffirmed. As celestial as all of that sounds, life does happen, and people often lose their way. However, the innate and viable sense of devotion, even at one’s darkest and full of doubt moments, is what brings people to pilgrimage. It instills a sense of trust; trust to completely detach, trust to enter the fog, and trust that you will find your way out on a path to a new beginning.

All sites of pilgrimage have one principal thing in common: they are sites where in which miracles are believed to have happened, still happen, or may happen. Thus, creating an ideal oasis for healing a lost soul. The Christian faith emphasizes personal exposure to these sites, creating an experience where all the senses are engaged, and in a sense you give yourself over to the healing properties of the spiritual world.

One of the most famous and revered pilgrimages is el Camino de Santiago de Compostela. The site itself is the Cathedral of Santiago where the shrine of St. James rests. Those who embark on this pilgrimage are said to be going “the way of St. James.” As the legend goes, St. James was an evangelist of Hispaniola, who was ultimately martyred because of his efforts. This was around the seventh century, and to punish all of his followers, his body was buried in a secret location; one that nobody would be able to find and pay respects to. Around the ninth century, it is said that a hermit, by the name of Pelayo, rediscovered the tomb of St. James, over which a cathedral was subsequently built. That cathedral is now what is referred to as the Cathedral of Santiago, and it is located in the town of Galicia. By the mid-ninth century the cult of St. James was rebirthed, and a century later foreign pilgrims were rapidly increasing. By 1200, the pilgrims traveling to the Cathedral of Santiago outnumbered those going to Rome. This was an incredible rarity because Galicia was considered to be a remote area, in comparison to the hugely attractive city of Rome.

“This cult was based firmly on the belief in the corporeal nature of the supernatural world and its close contact with and its influence upon the natural world of living men” ~(Costen, 2002, pg. 138)

The journey to the Cathedral of Santiago is all by land. Throughout the years many routes have been formed are followed by most. Many choose to start in a central location of France, others start in the Pyrenees; regardless of where one starts, there are multiple established paths leading to Galicia. The most prominent routes were created in hopes for pilgrims to be certain of meeting others along the way. Along the Camino, travellers are sure to find an abundance of accommodations within hostels, churches, and even hospitals. All the towns are very receptive and inviting, many travellers find that they are welcomed with open arms. As one could guess, “the climax of the journey” is reaching the Cathedral of Santiago (Costen, 2002, pg. 149). Once at the Cathedral, pilgrims often attend Mass, kiss the relics, and present some form of offering. The Cathedral is considered the end of the pilgrimage, however, some pilgrims travel on to Cape Finnisterre; the farthest west a pilgrim could travel in Europe. Standing on the edge of Cape Finnisterre is said to be one of the most surreal and powerful experiences. All in all, pilgrims are encouraged to go at their own pace, and often those traveling with some form of sickness take months to reach the Cathedral.

Why the way of St. James? Why was the Cathedral of Santiago an extraordinarily valued destination for pilgrimage? What kept the cult of St. James alive? The first important factor to consider was the persistent desire to have a connection or relationship with God. The Cathedral of Santiago provided a tangible source of His holiness. Saints were considered one of the closest and most viable connections to God. Furthermore, St. James was not only an apostle, but also a blood relative of Christ, thus ranking him fairly high in terms of power and influence. Secondly, the Church was completely in support of the Cathedral of Santiago and encouraged its followers to be a part of this feverish cult. Thirdly, the faith in the miracle and the unrelenting passion of the pilgrims dismissed any possible question as to whether the legend held any sort of truth. Fourthly, “to be free of spiritual sickness”, that is to lift the burden of sin, was a crucial element to the pilgrimage fervor. Forgiveness, being one of the most prominent services Christianity offers, made this possible. Then in 1095, the first crusade was announced, and those who took park were promised the attainment of absolution, the ultimate freeing of all sins. Unfortunately, many could not participate, but to their gratitude, they were offered an alternative solution: pilgrimage. Thus, pilgrimage became a very powerful method of receiving atonement for one’s sins, and many chose the way of St. James. Lastly, and most importantly, el Camino de Santiago de Compostela gave people a truly beautiful thing; the pilgrimage “some very real interior need” (Costen, 2002, pg. 142). Pilgrimage provided a way for all members of the Christian community to become closer to God, to restore their faith, and to secure their salvation. The way of St. James provided a way to regain spiritual health, and that is something that everyone needs at some point in his or her life.

In 2010, a movie entitled “The Way” was released, depicting the profound journey of El Camino de Santiago de Compostela. The storyline centers on a father, played by Martin Sheen, who is completely devastated when he learns that his son was caught in a storm in the Pyrenees, and did not survive. Previous to this tragic realization, the father and son are portrayed to be victims of the well-known struggle between autonomy and relatedness. As every parent and child know, finding a happy balance between meeting a parent’s expectations and a child’s desired path is not an easy task. Martin Sheen, as a prominent doctor, emphatically disapproves of his son’s seemingly arbitrary and frivolous life decisions. However, when he flies to France to collect his son’s remains, Martin Sheen realizes that in his last days, his son was traveling the way of St. James. As a tribute to his son, he decides to finish the journey. Visually seeing the journey, both geographically and emotionally, was an incredible movie experience. Martin Sheen undergoes a complete transformation within himself; from an uptight workaholic to an open an spiritual being. This paper has given light to the metaphor of fog. With the death of his son, Martin Sheen was bombarded by the fog, he was get stuck in it, but with trust in the unknown and faith in the journey, he was able to reach his absolution. Absolution from all the guilt of things left unsaid and of a live unlived.

The undeniable connection between the spiritual world and the natural world is a notion that has clearly been kept viable for centuries upon centuries. It was relevant during the life of St. James and it is relevant now in the twenty-first century. To endure extenuating circumstances that sometimes prompt a person to detach themselves from their world, and to feel completely lost and in need of direction, is a human experience. Within the Christian faith, this would be considered a rite of passage, traditionally a very normal and accepted state of being. As evidenced in the historical content of El Camino de Santiago de Compostela, pilgrimage was created as a way to enable us to break free of that fog, of the liminal phase. Pilgrimage is a way of attaining aggregation, and in doing so we are blessed with rebirth. We are granted a new beginning, a healthy soul, and the promise of a more fruitful journey.

Sources:

• Juergensmeyer, Mark. "Pilgrimage." In Encyclopedia of global religion. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications, 2012. 991-996.

• Reader, Ian, Tony Walter, and Costen, Michael. "The Pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in Medieval Europe." In Pilgrimage in popular culture. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan, 1993. 137-154.

• Swatos, William H., and Luigi Tomasi. "Homo Viator: From Pilgrimage to Religious Tourism via the Journey." In From medieval pilgrimage to religious tourism: the social and cultural economics of piety. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2002. 1-24.

• Turner, Victor. "Liminality." In The ritual process. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977. 1-20.

• Turner, Victor Witter, and Edith L. B. Turner. "Introduction: Pilgrimage as a Liminoid Phenomenon." In Image and pilgrimage in Christian culture: anthropological perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press, 1978. 1-39.