Mapping sitting:

datable structures, state imagination and the subordinated body

Ömür Harmansah ~ October 2, 2007 ~ Blue State cafe.

N.B. This piece was written in the context of my graduate seminar The Rise (and Demise) of the State in the Near East taught at Brown University's Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World in Fall 2007. I am grateful to the whole group for the intriguing and heated discussions in that seminar.

| Modernist architect Adolf Loos's notorious dictum "ornament is crime" continues to haunt me fourteen years after I finished architecture school. I was simply hoping to "loose" him at some point, but no. He found me again in David Wengrow's chapter on "the evolution of simplicity" (Wengrow 2006): he had surreptitiously sneaked his way into this book on the archaeology of early Egypt, parading as an eccentric character who sees "the evolution of civilization [as] tantamount to the removal of ornament from objects of use." Striking as he may sound in this context, he actually represents the central modernist discourse in architecture. For our rebellious postmodern little minds, Loos's statement was still equally forceful for us for what it represented: the functionalist view of modernist architecture that saw ornament and structure as distinct entities and sacrificed the former for the purity of the latter. This of course is not a simple and naive act: the representational surfaces of buildings have always been associated with references to the past, local identity and narrativity, with which modernism has had a sour relationship. The utopian project of modernity as the brainchild of modern European nation-state ideologies, promoted the idea of the "democratization of everyday life" which can now be read as subordination of the embodied self within the context of panoptically controlled urban landscapes of Hausmann, Mussolini and others. |

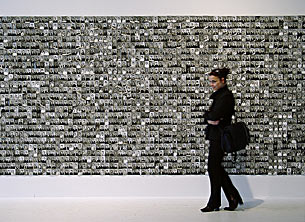

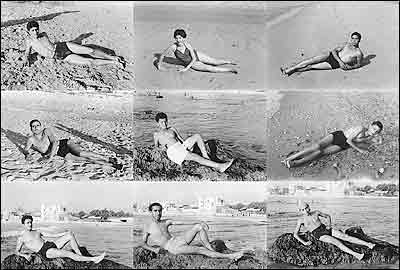

I will turn here to Walid Raad and Akram Zaatari's project "Mapping Sitting" which explores the direct implied relationship between the state and the individual by looking at the modern (Lebanese) state's practices of "imaging" its citizens and its creation of "datable structures" (Bassil et. al. 2002). They particularly explore the "everyday vernacular" photographs such as "identity" (or "Passport" photographs as they are called here, "vesikalik" [lit. documentary] in Turkish), and the "surprise" snapshot photographs of street photographers. This is in fact an impressive piece I have seen in person at Reed College. The exhibition strikes you by looking at an everyday practice of visualization which documents a non-coercive aspect of stately impact on our lives: the way we pose for a photograph, the way we are taught to pose for a photograph, our learned gestures and bodily twists, seemingly so naive and non-ideological, "the techniques of the body" as Marcel Mauss wrote about it. A corpus of bodily knowledge that is constituted by us, our own practices and our own awkward relationship with the state.

When Walid discussed his project with my class (Introduction to Art History at Reed College), he referred to "datable structures" the organizational state practices that transform every citizen into a database entry, counted in population statistics, accounted for a single vote in elections, surveyed by obnoxious marketing interviewers, photographed and documented in state documents, birth certificates, death certificates, passports, ID cards. Remember the border crossing scene in Babel. These can be understood as state practices of the bureaucratic kind, techniques of governmentality, which creates taxonomies of the material world, through the use of classificatory schemes. State flourishes as the world is bureaucratized. What is fascinating is that these practices cannot solely be ascribed to state agencies: they are produced and reproduced in the social world, as they become markers of collectivity.

Now let me return to antiquity... Having spoken about the regularization and bureacratization of everyday life in the socila world of the state, it may be helpful to consider then David Wengrow's recent discussion of state formation in Early Egypt (in the above mentioned chapter), and his powerful argument a concerning the "aesthetic deprivation of the elite," "simplification of everyday practices" or the evolution of simplicity in material culture. Speaking of the processes of urbanization and state formation in the ancient Near Eastern world, it is crucial to reconsider the transition from the uniquely elaborate, visually striking, technologically complex Hassuna-Samarra-Halaf pottery into the bevelled rim bowls of the Late Uruk period, as he also does in a series of articles (e.g. Wengrow 1998). Objects are "disentangled from social processes that invested them with particular life histories" (Wengrow 2006: 152). It is also possible perhaps to speak about the invention of writing as an institutional intervention to exchange systems, which can then be easily recorded, documented, therefore watched over. Why do we have profession lists among the archaic texts from Uruk?

Mitchell Rothmann's recent attempt to understand state formation with the old paradigm of the duality of elites and "common people" through reading archaeological material is therefore not quite effective as it still operates within the old social evolutionary models (Rothmann 2007. Note for instance the unfortunate comments on the "common people" blundering in false consciousness in p. 250-251), while Wengrow's interest in using a similar corpus in looking at the state practices in close relation to the remaking of the human body provokes new and exciting research possibilities. It is useful to quote once again Wengrow here quoting Alfred Gell quoting Foucault quoting who knows who. "The body is directly involved in the political field; power relations have an immediate hold over it; they invest, mark it, train it, torture it, force it to carry out tasks, to perform ceremonies, to emit signs" (Wengrow 2006: 153).

This, for me, sums up brilliantly the complex interaction between the state and the subjectified human body.

Works Cited

Bassil, Karl; Zeina Maasri; Akram Zaatari in collaboration with Walid Raad; 2002. Mapping sitting: a project by Akram Zaatari and Walid Raad. Mind the Gap- Foundation Arabe pour l'Image. Beirut.

Rothman, M.S.; 2007. "The archaeology of early administrative systems in Mesopotamia" in Settlement and society: essays dedicated to Robert McCormick Adams. Elizabeth C. Stone (ed.). Cotsen Institute of Archaeology (UCLA): Los Angeles, 235-254.

Wengrow, David; 1998. “The changing face of clay: continuity and change in the transition from village to urban life in the Near East,” Antiquity 72: 783-795.

Wengrow, David; 2006. Archaeology of Early Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.