In his chapter on dimensions of power in early states, Norman Yoffee advocates the use of differentiation and integration as productive analytic tools for studying the state. Yoffee argues that the utility of these terms/concepts/processes lie in the material evidence they may leave behind for archaeologists to uncover and study: “Kinds and amounts of social differentiation and integration have been successfully gauged in the archaeological record” (p. 32). His attention to questions of epistemology and methodology—i.e., what we can know and how we can know it—offer a departure from many other theorists of the state, who often seem to make leaps to theory from inadequate (or at least ill-explained) material data.

However, Yoffee’s subsequent discussion of integration leads to some problems. First, he writes that integration “can be measured in the number and nature of symbols of incorporation as well as in the tools of oppression” (p. 33). This is little more than a semantic quibble, but the idea that the nature of symbols or tools of oppression (or any social behavior, practice, intentionality, etc.) can be “measured” does not seem sound. If human agency could be quantified, our jobs as archaeologists, or social scientists more generally, would be easier and, in my opinion, less interesting.

Leaving this minor point aside, since I do not necessarily think that Yoffee intended the sentence quoted above to be interpreted so literally, we can move on to a related issue Omur brought up in class. In discussing symbols of integration, Yoffee argues that:

Such symbols include ritual spaces, temples, palaces, monuments, and artifacts that represent public identity. In states these symbols are produced and maintained by people who are specialized precisely in the ideologies that legitimize the order of stratification of differentiated groups and individuals. States have the power to disembed resources from the differentiaed groups for their won ends and glorification, not least because symbols of incorporation are so critical in establishing the legitimacy of societies (p.33).

As Omur argued, in Yoffee’s formulation correlates of these symbols, such as the monumentality of architecture, are seen as deliberate products of “the state,” which in turn implies that the state preceded the development, materialization, and dissemination of symbols. This leads us to ask whether the production of symbols is always a deliberate, ordered act and whether a State needs to exist in order for this production and proliferation to occur. I think many of us, myself included, would answer in the negative to these questions, recognizing a more organic growth of symbols, symbolism, and symbolic behavior. Space, place, ritual, monument—all may arise unintentionally or on contested grounds or in ways that change significantly through time. This point has been made before in this class.

As I rethought some of Yoffee’s arguments, I became increasingly concerned with his lack of attention to more “organic” processes, especially as related to urban growth and architectural monumentality. For instance, Yoffee uses James Scott’s discussion of legibility to explain the codification and “simplification” of society by the state. Although he cites examples from Scott that deal with city organization and planning (e.g., the discussion of “villagization” in Tanzania, p. 93), Yoffee does not discuss these issues with respect to legibility. However, I think this would have been a fruitful way to problematize the structured and deliberate ways “symbols of integration” are discussed in his book. For instance, unlike many other states discussed in the book, Maya city-states were not organized in an obviously coherent fashion. The spatial arrangements of buildings did not follow any sort of grid or linear pattern (compare, for instance, the plan map of Copan with Teotihuacan, two contemporaneous cities in contact with each other. In fact, the founding dynast of Copan, K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’, was likely from Teotihuacan by birth). Instead, large, monumental masonry buildings appeared in clusters with differing orientations and relationships with each other, which were added to as the population expanded, as new kings engaged in building projects, and as the number of nobility grew. Does such a spatial organization imply a lack of legibility? Or that “legibility” is a culturally-specific phenomenon? I think at the very least in demonstrates that, as symbols of integration, monumental architecture and space do not always develop as the direct result of explicit state deliberation, but rather that they evolve organically.

Furthermore, Yoffee seems to equate the notion of power, the symbolism of monumentality, and ideology:

Monumental art and architecture “are symbols of the new ideologies of states, that is, foremost, the idea that there should be a state, centralized leadership, elites and dependants, the powerful and the powerless…The symbols of this ideology are everywhere—in decorative arts, architecture, monuments, and buildings and in the very construction of space in sites” (p. 39).

In considering the symbolism and communicative potential of these “symbols of ideology” I returned to Keffie’s question about why people accept the state in the first place. To draw from another Maya example, the “monumentality” of public buildings and plazas—so often seen as the material manifestation of kingship, centralized rule, and the state—has its roots in humble, domestic structures. The layout of a triadic grouping of buildings with a large mound, usually mortuary in nature, at the eastern side characterizes many of the famous architectural complexes of the Maya. However, this same exact pattern is seen in housemounds from the hinterlands of sites, as well as from Preclassic times (see the examples from Tikal and Uaxactun). This suggests that the monumental architecture, one of Yoffee’s symbols of integration, has its roots in pre-state times, practices, and beliefs.

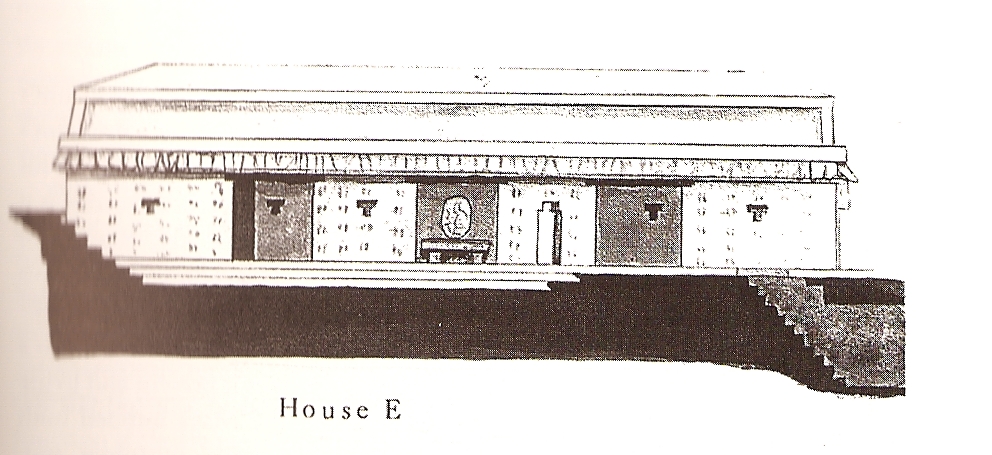

Similar incorporation of non-royal or non-state architectural attributes can be seen, for instance, at Palenque, where palace buildings had mansard roof forms, lined with slivers of slate tiles, that likely mimicked the thatch roof houses of the hinterlands.

House E from Palenque, with a mansard roof form. The bottom edge of the roof has splinters of slate tile, which resemble thatch roofs

The question then remains whether the state appropriated these attributes of domestic, non-elite households deliberately as a way to legitimize power and control (thus providing one potential answer to Keffie’s question: people accepted the state because the state was just like them, only write large) or whether the intentionality was more subtle or less conscious, i.e., that the development of monumental architecture commissioned and maintained by the state appeared in forms and arrangements already familiar as the result of a more natural and organic process.