Paper in Progress!...

Approaching the Near Eastern state:

discourses, practices, performances

Ömür Harmansah ~ Starting on October 20, 2007 ~ Multiple sites of writing including My office, Blue State Cafe and at home.

VIDEO: Performing the State Military ceremony at Ataturk's Mausoleum in Ankara.

VIDEO: Performing the State Military ceremony at Ataturk's Mausoleum in Ankara.

"The state... is not an object...(but) an ideological project. It is first and foremost an exercise in legitimation... It conceals real history and relations of subjection behind an a-historical mask of legitimative illusion... The real official secret, however, is the secret of the non-existence of the state"

Abrams 1988: 76-77.

"The scholarly analysis of the state is liable to reproduce in its own analytical tidiness [the] imaginary coherence and misrepresent the incoherence of state practice" (Emphasis added)

Mitchell 1999: 76.

1

Here I will attempt to bring together a few streams of thought provoked by reading and discussing the state in our ongoing seminar The Rise (and Demise) of the State in the Near East. We are at a point in the semester when ideas about the state have come to some level of maturity that there is always urgent need for writing them down. Yet the reader should consider this as a work-in-progress and not a set of polished arguments.

2

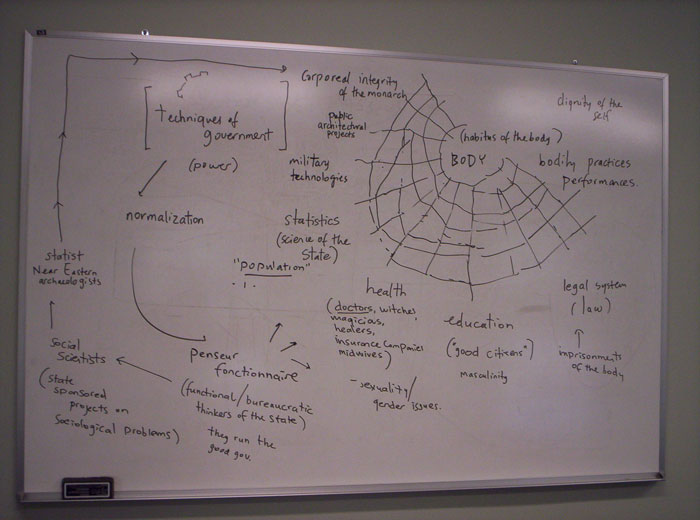

In contrast to what its title might imply to the traditional school of state-oriented scholars, this seminar was in fact not intended to trace the processes of state formation in the Ancient Near East, and certainly did not exclusively focus on the "economic and social transformations accompanying the emergence of urbanized state societies in fourth and third millennia B.C." (original course description in the books). No, not at all. Instead, we started the seminar with an interest in turning this historiographic tradition on its head by interrogating the widespread obsession among academics with finding, identifying, classifying, quantifying, and talking about the state in the ancient Near Eastern history in particular and the rest of ancient world in general. It is of particular interest that archaeological evidence from the material worlds of the early Near East have so far been candidly written under the notoriously evolutionary narratives of the state from chiefdoms to city-states and to empires, while the artifacts, texts and spaces of the past were painstakingly linked to the ideologies, power structures and political economies of the state (see e.g. Adams 1966; Stein and Rothman 1994; Feinman and Marcus 1998). The practitioners of this statist academic practice (identified below as "penseur fonctionnaire"=bureaucratic thinkers after Gramsci 2000: 307 and Bourdieu 1999: 55) who enjoy working within the comfort zone of macro-models and grand narrative scenarios, are now being rigorously challenged from many angles (e.g Mitchell 1999, Abrams 1988, Routledge 2004, Bartelson 2001). The task was to bring to discussion such criticisms of (the existence and importance of) state itself and offer alternative readings of the ancient Near Eastern pasts.

3

Bruce Routledge (2004), in one of the rare critical contributions to the study of Near Eastern states, has ingeniously shown that while the definition of the state as a monolithic, autonomous entity, as a universal category, as an absolute agency, a solid system of decision-making has been increasingly and rather rigorously put to question in post-colonial theory and political science, the fields of Near Eastern archaeology and history never had such a problem. In fact, within the tidy framework of evolutionary models, ancient states appear as disturbingly coherent entities with their institutional structures, ideological apparatuses, monopolies of economic and socio-political processes and most importantly their unquestioned materiality (typically Mann 1986). While social hierarchies dominate this absolutist model, concepts of heterarchy and anarchy are seen as dangerous paradigms that threaten the statist statusquo (see e.g. Gil Stein's comments on heterarchy in Stein 1998). Evolutionary theories of the state base themselves on a desire to explain macro-scale social change at the institutional and political organizational level through rationalized linkages of causality among historical phenomena. In this frame of reference, historical events and selected social transformations should be logically linked to each other forming a linear trajectory of cause-effect relationships. Evolutionary theory classifies past societies into inferior (noncomplex) and superior (complex) ones, alluding to the implied imbalances in the contemporary world of capitalism between the West and the Rest. In this sense, evolutionary theory appears not only as a functionalist modernist utopia of straight-jacketing of history into imperialist grand narratives, completely disassociated from individuals, actors of the past, but also as a discourse that conforms and aligns with the state discourse itself. For the states, characteristically, present their institution as a natural process (essential for its legitimization in the mental world of their subjects) and therefore favor illusory narratives of the state's own evolution from its genesis to its sophisticated organization of the social world. This is particularly striking for instance in the so-called "terra nullius" discourse that the states adopt frequently: cultivation of "untouched" and "uncivilized" natural landscapes into accultured constructed environments through cultivation and monumentalization. Evolutionary theorists fall into the trap of precisely this state discourse and inevitably become intellectuals of the state apparatus (Gramsci), the "penseur fonctionnaire". It is most appropriate to repeat Bourdieu's famous sentence here: "To endeavour to think the state is to take the risk of taking over (or being taken over by) a thought of the state, that is, of applying to the state categories of thought produced and guaranteed by the state and hence to misrecognize its most profound truth" (Bourdieu 1999: 53).

4

4

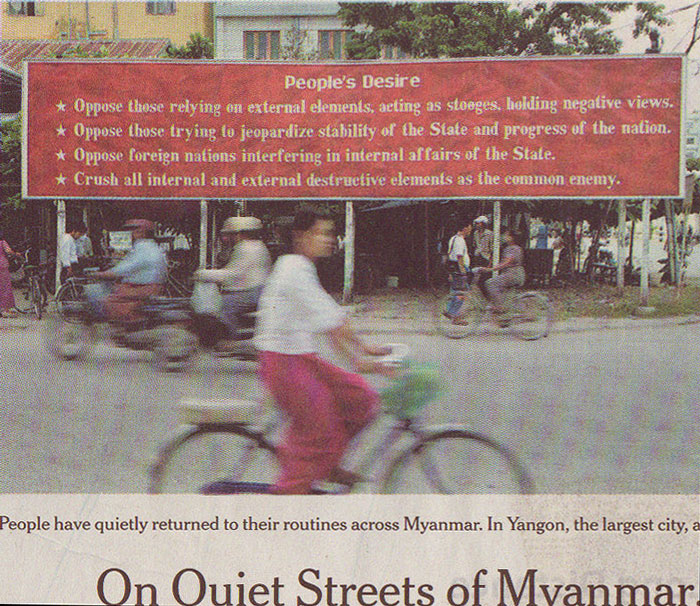

The state then can only be understood (from its margins), NOT as a monolithic and coherent entity, but actually as a set of practices, performances, and discourses, and by deconstructing this manufactured, illusory image of the state as a thingly whole!. Timothy Mitchell (1999: 81) suggests that "a construct such as the state occurs not merely as a subjective belief, but as a representation reproduced in visible everyday forms, such as the language of legal practice, the architecture of public buildings, the wearing of military uniforms, or the marking and policing of frontiers. The ideological forms of the state are an empirical phenomenon, as solid and discernable as a legal structure or a party system." Our interests have been focused precisely on this aspect of the state: its appearances in the everyday life of its citizens, its representations and legitimating practices generated by the very society itself. The state presences as it aspires (literally "breathe upon") to shape our bodily practices, regulate our collective identities, structure our gestures, transform our built environments, configure our senses of collective pasts, exert violence over us. As Mitchell has noted, a seperation of state and society is one of the main features of statism: I would argue that precisely this image that presents a neat separation of the state (a decision making machine) and the society (subject populations). The embeddedness of the two is most profoundly apparent in the state's continuous, unrelenting practice of appropriating social practices to construct its own image. The main function of state practices is to transform illegible, complex, chaotic human practices into simplified, legible, effective spectacles in the social world. This, James Scott, refers to as a "greatly schematized processes of abstraction and simplification" (1998). Perfect example to this is the standardization of family naming practices by the modern nation-states with the introduction of a "first name" and a "surname".

State Performances:

Image Credit: New York Times, Oct 21, 2007.

Image Credit: New York Times, Oct 21, 2007.

Bibliography

- Abrams, Philip; 1988. “Notes on the difficulty of studying the state,” Journal of historical sociology 1: 58-89.

- Adams, Robert McCormick; 1966. The evolution of urban society: Early Mesopotamia and Prehispanic Mexico. Chicago: Aldine Publishing.

- Bartelson, Jens; 2001. The critique of the state. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre; 1999. “Rethinking the State: genesis and structure of the bureaucratic field,” in State/culture: state-formation after the cultural turn. George Steinmetz (ed.). Ithaca : Cornell University Press, 53-75.

- Feinman, Gary M. and Joyce Marcus (eds); 1998. Archaic states. Santa Fe; School of American Research Press.

- Gramsci, Antonio; 2000. The Gramsci Reader: Selected writings 1916-1935. David Forgacs (ed.). New York University Press.

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara; 2006. Performing the State: The Jewish Palestine Pavilion at the New York World's Fair, 1939/40.

- Mann, Michael; 1986. “Societies as organized power networks” in The sources of social power: Volume 1. A history of power from the beginning to AD 1760. Cambridge University Press, 1-33.

- Mitchell, Timothy; 1999. "Society, economy and the state effect" in State/culture: State-Formation After the Cultural Turn. George Steinmetz (ed.). Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 76-97.

- Nichols, Deborah L. and Thomas E. Charlton (eds.); 1997. The archaeology of city-states: cross-cultural approaches. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Rothman, Mitchell S.; 2001. Uruk Mesopotamia & its neighbors : cross-cultural interactions in the era of state formation. Sante Fe, NM : School of American Research Press.

- Routledge, Bruce; 2004. Moab in the Iron Age: hegemony, polity, archaeology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Scott, James C.; 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 11-52.

- Stein, Gil and Mitchell S. Rothman; 1994. Chiefdoms and early states in the Near East: the organizational dynamics of complexity. Monographs in World Archaeology 18. Prehistory Press.

- Stein, Gil; 1998. “Heterogeneity, power and political economy: some current research issues in the archaeology of Old World complex societies,” Journal of Archaeological Research 6: 1-44.

- Wittfogel, Karl August, 1957. Oriental despotism: a comparative study of total power. New Haven : Yale University Press.