Earth Undone, or the Globalization of the World Picture

Benjamin Lazier

Reed College/Stanford Humanities Center

In 1990, the German astronomers Freimut Börngen and Lutz Schmadel named an asteroid after one of the foremost political philosophers of the twentieth century, the German-Jewish émigrée Hannah Arendt. Whether Arendt would have appreciated the gesture is uncertain. After all, her philosophical masterpiece, The Human Condition, opens by voicing grave concerns about Sputnik. Man had for the first time propelled his artifacts into the beyond, and he was likely to follow by propelling himself as well. But the desire to depart from the scene of the world, she felt, meant also to figure the world as something worth leaving. To emancipate ourselves from its physical limits—gravity—meant also to emancipate ourselves from the gravity of its moral claims upon us. Sputnik therefore embodied an impulse already much in evidence on earth—to create an artificial planet. In Sputnik the ambitions of modern man lay revealed.

Arendt’s approach to the problem was idiosyncratic. Her concern, however, was not. Anxiety about the triumph of the made over the grown, of artifact over organism, was shared by a huge swath of twentieth-century thinkers across virtually every domain of thought and culture. A history of the anxiety and the distinction invoked to explore it is perforce an intellectual history of the twentieth century. It is also a history from a perspective to which we are unaccustomed, as it cuts so decisively across both disciplinary and national borders.

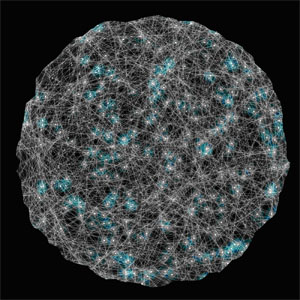

This essay is a small gesture in the direction of such a history, organized around one of its most revealing moments. It considers how Arendt and other mid-century intellectuals (Heidegger and Hans Blumenberg above all) reflected on what we see and what it means when we look back upon the earth from beyond. This essay also has a second, broad aim. It considers whether a history of philosophical reflection on images of the planet can help us understand what is at stake in recent globe-talk: historically, how what we sometimes call earth, sometimes world, sometimes planet has become “globalized,” and what this innovation in nomenclature really means.

A Satellite Skyscape over Los Angeles