|

|

Technologies of Government: Police Stations, Urban Space, and Bureaucracy in Lisbon, c. 1850-1910

Gonçalo Rocha Gonçalves1

Abstract

The evolution of police stations reveals crucial aspects in the modern development of the police force and of policing practices in general. The spatial rationalities involved in the territorialization of the State, the formation of different spaces where the sociocultural and technical dynamics of the police were engendered, and the emergence of places through which communities could visualize and interact with the State were all major components of this process. This article seeks to examine these issues, assessing their significance for the working lives of policemen and for the interactions between the police and the local population in Lisbon in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Keywords

Police; State-Building; Territorialization; Bureaucracy; Lisbon

Resumo

As esquadras de polícia sinalizam aspetos cruciais do moderno desenvolvimento da polícia e do policiamento. As racionalidades espaciais na territorialização do Estado, o engendramento das dinâmicas socioculturais e técnicas que marcaram as forças policiais e o surgimento de "lugares" através dos quais a sociedade visualizou e interagiu com o Estado foram componentes essenciais deste processo. Este artigo procura examinar estas questões, avaliando sua importância nas vidas de trabalho dos polícias e nas interações entre a polícia e a população em Lisboa no final do século XIX e início do século XX.

Palavras-chave

Polícia; Construção do Estado; Territorialização; Burocracia; Lisboa

In Portuguese, the name given to urban police stations is esquadra—esquadra de polícia. Etymologically, this word has two different roots. As a noun, it stems from the Italian word squadra, commonly used in naval and army contexts to refer to a set of ships or part of a battalion. Today, in Italian, this word means “team,” among other things. A second origin of the word lies in the Latin verb squadrare, which means “to reduce to squares” (Machado 1977: 470). The latest official dictionary of the Portuguese language attributes the word esquadra with two meanings relating to the police: a geographic section within a police division; and a police station. To illustrate its current usage, the dictionary provides the word in context: “He/she complained at the nearest esquadra (police station)” (AAVV 2001: 1551). There are thus two current meanings for the word esquadra when associated with the police - one has a territorial sense, denoting a police zone, a spatial portion of the city, while the other sense refers to a physical place, a building, the place where police services are located, and which also conveys a sense of spaciality.

The association between the word esquadra and the police is directly linked to the foundation and development of the Polícia Civil from the 1860s onwards, since it had never previously been used by any other police force. Until the second half of the nineteenth century, Portuguese language dictionaries only stated the naval and military meanings of the word – a group of ships or men. In 1877, the 7th Edition of the Morais da Silva dictionary, the most important dictionary of that period, still indicated only the naval and military meanings (Silva 1877: 723). Only in its 8th Edition, published in 1890, did the entry ‘Esquadra’ incorporate its connotations with the police, both in its territorial sense, as in belonging to someone/something, and in its reference to a physical place (Silva 1890: 839). Its meaning as a place must have gained ground very rapidly, as another dictionary, published in 1911, attributes only one meaning to the word esquadra—that of the police station (Figueiredo, 1911: 802). Nevertheless, in the official discourse of the time, esquadra was still used primarily to refer to a body of men allocated to a designated police area, thus mainly reflecting an administrative concept of territorial circumscription. In fact, police regulations rarely used the word esquadra to designate the place where police services were located. “Stations” (estações) and “headquarters” (quartel das esquadras) were the terms most commonly used to refer to the place where the police services were housed.

This article therefore focuses on the political and sociocultural process whereby a word was appropriated by the police in the course of its organization, initially being used to designate a body of men attached to a territorial district and ending up referring mainly to a physical place, the police station.2 By examining the processes involved in the organization of the police force and the management of its daily life, I seek to describe the development of the technologies of government used to control the population of the country’s capital. In the wake of the founding of the constitutional monarchy in 1834, a new police force was set up—the Guarda Municipal. In the 1860s, however, a new movement of police reform, underpinned by concepts of professionalization and bureaucratic rationalization, led to the launch of the Polícia Civil, which was designed to serve as a modern, urban, and civilian police force engaged in the duties of crime prevention and the ‘domestication’ of the public space. In the following decades, the two forces co-existed in the city and the process of police modernization continued (Gonçalves 2016). The Polícia Civil became responsible for the activities of day-to-day policing and the Guarda Municipal specialized in the growing demands for the maintenance of public order (Palácios Cerezales 2011; Gonçalves 2014).

There were also other institutions entrusted with the role of enforcing the law and public order in the city, most notably the local government bodies known as regedorias,with their regedores and cabos de polícia (Santos 2001). Although they still continued to perform an active and important role until the end of the century, the voluntary and non-professional nature of these assemblies ultimately led to a fall in the number of both their agents and physical establishments (the regedoria offices or stations) and consequently diminished their relevance in the city’s policing arrangements (Gonçalves 2015: 478). In territorial terms, the areas covered by the regedores and the Polícia Civil were the same. However, while in other Portuguese cities regedorias still performed numerous police services, in Lisbon they were increasingly seen as a complementary form of policing, with the Polícia Civil playing the major role (Gonçalves 2012). This article thus focuses its attention on the professional police force, which was more directly controlled by the central government.

The study of the organizational history of the police force more frequently dwells on the question of what it should have been, rather than on how it actually functioned at the day-to-day level. The sources used in this work propose a bottom-up approach, aiming to discover what happened at this everyday level. Therefore, besides government reports and other administrative documents, the Polícia Civil’s daily orders are the main source used here. This source constitutes a true ‘diary’ of a police force; through it, we can uncover an organization in the making. The daily orders were written by the general commissioner and distributed to all police stations. Since they were posted on the police station notice board and read out loud to the men on parade, every policeman would be aware of the contents of these orders before being assigned their own specific duties. Through these rules and regulations, not only can we form a picture of what the upper police hierarchy envisaged as the ideal procedure, but we can also understand how things actually happened on the ground. The next section of this study examines the spatial rationalities that existed within the old Guarda Municipal. The two subsequent sections are then devoted to tracing the evolution in the organizational structure of the new police force over the following decades. First, we consider how the growing number of police stations developed into a genuine network with the help of new technological devices. Finally, we examine the physical design of police stations and consider how this, in turn, impacted on the public visibility of the police’s authority.

Changing Spatial Rationalities

Until the 1860s, the term police station (estação policial) referred to those places where the Guarda Municipal deployed some of its men to stand on watch. From the correspondence addressed to the Ministry of the Interior, we can see how the Guarda stations and police patrols (conducted either by the cavalry or the infantry) were conceived of as complementary but opposite forms of policing. Men assigned to work at the stations remained there throughout their entire shifts, while those assigned to conduct patrols did not report back to the stations, but instead to the central barracks. Only on occasion, and always at night-time, were the men assigned to the stations also required to perform patrolling duties.3 When asked by the Ministry about the appropriateness of establishing a station at the city’s Escola Politécnica in August 1862, the Guarda commander stated that “the number of stations is already very large in relation to the available Guarda force, and this means reducing the number of patrols, which remain absolutely essential.”4 On another occasion, when the inhabitants of a few farms on the outskirts of the city requested the reopening of a station that had recently been closed down, the Guarda commander argued that “the greater the number of stations, the smaller the number of patrols, which are still recognized as being necessary.”5 As these stations implied the assignment of one man to one place, they were regarded as a better means of protecting that specific place, whilst patrols being carried out over a defined area were in turn perceived as less effective but inevitable, given the resources available. Particularly in the city’s more central areas, the so-called stations were little more than sentry-boxes manned by one or two guards and were not designed for the completion of any paperwork, for example. The number of guards most commonly assigned to these stations ranged from six to ten. With the men working shifts lasting a maximum of six hours, each station would have had two or three policemen on duty at each moment of the day. Stations and patrols were sometimes complementary, but intrinsically they represented different forms of policing. An area would either have a station or be patrolled by the infantry or the cavalry. More importantly, however, they revealed two different spatial rationalities in terms of policing: one based on a static position and another based on the mobility of surveillance.

The role of observation that was performed by the Guarda stations was clearly conveyed in May 1869, when the owners of a tobacco factory located in a working-class area of the city near the waterfront requested that the Ministry establish a Guarda station there by transferring another one from a nearby location. Called on to express his opinion, the commander opposed the transfer, stating that the existing station “is one of the best located [of all stations] because, with its view, it overlooks a large area of land occupied by streets and alleys” and, furthermore, it “keeps many sailors and other individuals who continually flock to the public houses nearby under surveillance.”6 The visibility and coverage that the location provided of a certain territorial district, coupled with its proximity to areas of greater risk, proved to be the most important factors in determining the geographic positioning of the station.

One important characteristic of the Guarda stations, which clearly demonstrated their significance in the establishment of policing strategies, was their constant instability. They were frequently established, disbanded, and then set up again in a completely different location. A good indication of this volatility is provided by the great difficulty encountered in ascertaining just how many stations actually existed or discovering how this number evolved over the course of time. The decision to open, close or move Guarda stations from one place to another seemed to be based more on the always precarious existence of such premises (particularly when these were provided free of charge) and on the resources and men that were available in a particular area rather than on any pre-established assessment of the city’s territory or the devising of a policing strategy for the city as a whole. In Porto, in 1863, a shortage of manpower was the argument invoked by the commander for closing two stations near to the city gates and consequently, in the words of someone who wrote to complain to the Minister of the Interior, leaving the “inhabitants of one of the city’s outlying districts completely abandoned and without any help.”7 On the contrary, in August 1864, the outbreak of a conflict between a tobacco factory’s workers and its owners, and the municipal authorities in general, led to the opening of a station composed of one sergeant and six guards in order to “provide protection to employees” and “maintain the workers in peace and good order.” This station was removed after just a few days and re-established at its original location, later being removed again at the beginning of 1865.8 The concept of a police station that prevailed in the thinking of the police authorities derived purely from the military concept of a static distribution of the force throughout the territory, in an arrangement that allowed for its redeployment according to the changing circumstances.

In Lisbon, in March 1864, the Hospital São José requested the opening of a Guarda station on its premises. The institution’s director argued that a municipal police station at a hospital was more than justified on the grounds that people injured in brawls, as well as demented persons, often attracted tumultuous crowds, and, furthermore, that criminals undergoing hospital treatment could easily escape. Reluctantly, the commander agreed to open a station there, but only by transferring one that already existed in a semi-rural area on the outskirts of the city, Sete Rios.9 This station already had a long history, having been housed on a nearby farm since January 1852. The farmhouse had originally been provided rent-free by the landlord, for the use of the police. However, in December 1859, the landlord met with the commander to inform him that he now needed the house for his own business, but that he would be prepared to let the station remain there were the Guarda to agree to pay an annual rent. For reasons that still remain unclear, this matter was only resolved in August 1860 when the Ministry agreed to pay the rent. By that time, however, the landlord was no longer prepared to rent out the house and the Guarda had to start searching for a new station in the vicinity. At the end of August, the commander wrote to the Ministry, saying that he had found the only house available in that area and requesting permission to rent it. The Ministry concurred, and the station was moved to a site near the terminus of a newly-established omnibus line.10 More than three years later, in December 1863, the new landlord of the same farm requested the Ministry to re-establish the station on the farm’s premises, once again rent-free. He complained that the farm had been regularly targeted by thieves because it was isolated, without any neighbors nearby. The Ministry consulted the Civil Governor of the Lisbon District, who was opposed to transferring the station to its previous location. He argued that the farm’s land was already being patrolled during the night and that the station’s current location was a very favorable one, since it was in a “central place” for that whole area.11 Thus, the station stayed where it was, even though, just a few months later, it was summarily removed to Hospital São José in a totally different part of the city. Hence, the existence of a station in one particular area did not amount to any previous systematic plan, but instead resulted from a process of negotiation between the authorities and other institutional and private actors in what amounted to a relatively uncertain and unpredictable process. The various contingencies that were involved in this process often dictated solutions that ran counter to whatever the authorities may have originally intended as the ideal organizational arrangement for policing purposes.

Another example of this instability occurred a couple of decades later. In 1885, a group of residents in a rapidly expanding neighborhood on the outskirts of the city, Campo de Ourique, successfully petitioned the Ministry to establish a Guarda station in one of the neighborhood’s new buildings, with the rent being paid by this group of citizens. Two years later, a member of this same group, Firmino Lopes, who had been named as the guarantor of the rent to be paid to the landlord, wrote to the Ministry, complaining that he alone was now paying all of the rent for the property where the station was housed. According to Firmino, many of the residents who had promised to pay part of the rent had left the neighborhood, and so Firmino was left to pay the rent by himself. For the commander, even though the station was “not very well located in relation to the area it was meant to police,” it nonetheless represented a useful station in an expanding part of the city, which, moreover, was not yet covered by the Polícia. In the end, the Ministry checked the funds that were available to pay station rents and agreed to meet the costs of this respective rent.12 The spatial rationality behind the Guarda’s structure was, as already noted, based not only on a combination of static and mobile strategies, but also on a process of territorialization. Thus, the whole structure was shaped by decisions made in the course of negotiations, in which the State did not necessarily take the first step, and inevitably resulted in an unstable territorial arrangement.

In late 1861, in an exceptionally rare situation when the policing system actually came to be discussed as a whole, the commander of the Porto Guarda voiced his concerns about the city’s growth, being aware of the extent of its expansion, the development of its thoroughfares and the size of its population, and raised the question of the overall “organization of a police system.” In addition to outlining the need to increase police numbers, he also proposed setting up stations on sites to be agreed upon mutually between the police commander, the Civil Governor and the city council. The stations had to remain in the same place for as long as possible in order to “obtain an accurate knowledge of the people circulating in that place.” Furthermore, the location of these stations had to be made public by posting notices all around the city.13 These recommendations were never actually implemented and the discussions that did take place between the Ministry of the Interior and the senior Guarda management clearly focused, instead, on the need to acquire more horses to deal with the growing threats to public order.

However, the proposals made by the commander of the Porto Guarda Municipal were not forgotten and were incorporated into the organization of the new police force. In the latter half of 1867, a series of operations took place in Lisbon as part of the process for setting up the actual body of the police, which involved the territorialization of the new police force. On July 8, less than a week after the publication of the law of July 2, the Ministry requested the Civil Governments of Lisbon and Porto to indicate the areas that would constitute the new police precincts. On July 25, these precincts were officially created.14 If the term “bureaucratic rationalization” can be used to describe specific actions and contexts, then it is ideal for describing operations such as this one. Resorting to an old form of spatial representation, the stations were divided into a hierarchy of separate spaces and described according to an inventory of different places. In a city still without avenues, this list of places amounted to thirty-five different classifications (street, square, alley, etc.). There were thus a total of 917 spaces distributed across 3 divisions. These divisions were subdivided into 12 esquadras andthen each of these was further subdivided into another 39 sections.

The notion of an esquadra or circunscrição de esquadra implied here the body of men allocated to a designated area (and not the headquarters of the police services, which were given the name of ‘postos’). Although the territorial component could be more directly attributed to the word circunscrição, the official use of the word esquadra (which was not always uniform) and the broader sense attributed to the word—as shown by the dictionary entries quoted above—denoted a meaning in which esquadra was associated with the component of a body of men and conveyed an intrinsic territorial sense.

The aim of rationally distributing the men throughout the urban space was clearly visible here. The geographic delimitation of the esquadras conveyed a notion in which the State played a much more active and systematic role in controlling and managing the urban territory. In comparison with the earlier systems, policing now demonstrated a much more active concern with guaranteeing the systematic surveillance of the space of the city.

Nodes in a Network

Who were the old and who were the new police? And just how ‘new’ were the ‘new’ police? When and where did they emerge? These are the questions that police historians have been continually discussing (Emsley 2007). While still incorporating characteristics of the old police, the Polícia Civil introduced innovations into the police’s relationship with the urban space and its impact on the organization and public visibility of the police authority. In the next two sections of this study, we examine the common links between these two processes—the more systematic spatial deployment of the police force and the construction of the tools and techniques needed for its internal supervision and control— while all the time stressing the centrality of the police station.

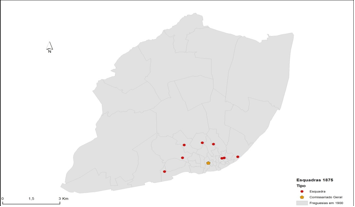

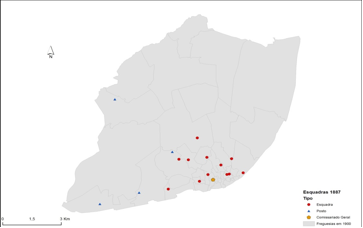

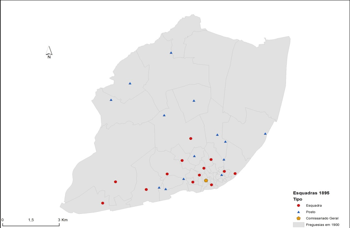

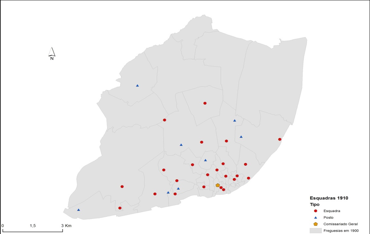

Particularly from the last decade of the century onwards, the number of police stations grew continuously. Even though the legal framework introduced in 1867 established a structure that was based on twelve police stations for the entire city of Lisbon, it was only after the 1876 reform that this number of stations was effectively implemented. Until then, and despite what was provided for in the law, there were, in fact, only nine stations.15 The reasons for this decision were not completely clear in the documentation that we consulted, but it was probably related with the lack of manpower and the lack of demand for policing in those areas where the stations were not established, namely the sparsely populated neighborhoods on the city’s periphery. However, from the mid-1880s onwards, the number of police stations increased significantly. In 1887, two stations and four of the newly-created postos (a smaller-scale version of the police station, which was under the command of the nearest station) were added to the original plan. This strategy then continued with the setting up of the postos: in 1895, there were fourteen of them, which were soon upgraded to the category of a station, along with another fourteen stations. On the eve of the Republican revolution, in 1909, there were twenty-four police stations and eight postos spread across the city. This growth in the number of stations was clearly linked to the evolution of the city’s population, which, from the mid-1880s until the 1930s, registered its highest levels of modern growth, rising from 227,674 inhabitants in 1878 to 594,390 in 1930 (Silva, 1997: 35).

This station structure was applied both to the sparsely populated, but increasingly urbanized, outskirts of the city (neighborhoods such as Benfica, Campo Grande, or Marvila) and to its densely populated centre (Bica and Bairro Alto, Alfama and Mouraria for example). From the police stations’ addresses, we can conclude that they appeared mainly in working-class neighborhoods located near the city centre and along the city’s waterfront. Postos, on the other hand, appeared in areas on the outskirts, such as Benfica, Laranjeiras, or Campo Grande,and, as these areas became more intensely urbanized, the postos were upgraded to full-scale esquadras. Each of these stations corresponded to a political and organizational exercise of mapping the city both in geographic and social terms. The establishment of each station was based on an assessment made by the police leaders of the human geography of the city, in keeping with its continuous transformation (see Maps 1, 2, 3, and 4).

Map 1 – Location of the Polícia Civil stations in 1875.

Source: All maps were made by the author with the assistance of Daniel Alves from the Faculty of History of the Nova University of Lisbon, using GIS software and based on the data of the Almanach Burocrático Geral, Distrital e Concelhio para 1875, which contains the addresses of the stations (Lisbon: Empresa Editora Carvalho, 1874), pp. 296-297.

Map 2 - Location of the Polícia Civil stations in 1887.

Source: Almanach Burocrático Comercial da Empreza Literária de Lisboa para 1887 (Lisbon: Empreza Literária de Lisboa, 1887), pp. 375-377.

Map 3 - Location of the Polícia Civil stations in 1895.

Source: Alexandre Morgado Guia do Forasteiro nas Festas Antonianas (Lisbon: Typ. Comércio, 1895), p.83.

Map 4 – Location of the Polícia Civil stations in 1909.

Source: Almanach Palhares para 1909: burocrático, comercial, ilustrado e literário (Lisbon: Palhares & C.ª, 1909), pp. 871-872.

The police reforms introduced over this period merely increased the organizational importance of police stations. In August 1893, the government embarked on the most extensive reform of the Polícia Civil that the force had yet experienced. Emulating the foreign police models already seen in previous decades (Gonçalves 2014, 2016), in the preamble to the text of this reorganization, the Minister of the Interior, João Franco, referred to the recent reform of the Parisian police force undertaken by the Préfet Lépine as a model for the reform he himself was implementing with the Lisbon police. One of the key decisions contained in this reform involved the organizational restructuring, centered primarily around functional specializations. The launching of three different divisions—“Public Safety,” “Administrative Police,” and “Criminal Investigation”—meant that the organization of the force effectively evolved from one that was predominantly structured on a territorial basis to one where the actual functions of the police were placed at the center of how these services were organized. The implementation of these new functional divisions was accompanied by the closure of the “Police Divisions” and their Commissariat buildings. Police stations, which formed the “public safety branch,” came under the direct command of the General Commissariat. The end of the commissariats reflected a clear indication of the growing importance of police stations.

Their increasing number and their growing importance as organizational units could have led to dangerous levels of autonomy of police stations and their independence from centralized control. This risk was however partly avoided by fostering the network nature of police stations through the adoption of the telephone. Before this, police communications were carried out by men circulating between stations. The daily orders, for example, were delivered each morning by a policeman who, on his way back to the headquarters, carried messages from the stations to the general police commissioner. The adoption by State institutions of the new communication technologies, such as the telegraph and the telephone, reveals a crucial aspect of the newly-emerging networked city in its response to urban growth and the outbreak of situations of crisis, such as epidemics, fires, and riots. This strategy represented both a technique to improve police response times whilst also increasing bureaucratic control over the men on duty. As in the United States, firefighters in Lisbon reacted more quickly than the police did in adopting the telegraph (Camelo 1971). Although the police also adopted the telegraph, it was the telephone that gained greater prominence within the organization. Unlike London, where the use of the telephone always remained limited (Williams 2014: 128), but rather like many American cities (Tarr 1992: 13), the telephone was adopted in Lisbon with an impressive rapidity soon after its invention and commercialization in the late 1870s; it did, after all, enable richer communication and made it possible to transmit more information than the telegraph.

The telephone gained greater prominence in Lisbon police stations as the “telephone room” rapidly began to play an important role at police stations. Together with shops, companies, banks, theatres, fire stations, and some private houses, police stations were among the earliest adopters of the telephone in Portugal. This was not the police’s first encounter with new communication devices. The telegraph had already been deployed previously, but was mainly used for communications between the General Commissariat and other authorities. Indeed, the telephone had been in use by the police since at least 1880 with the first daily order about telephone use being dated December of that same year.

During these early years, police telephones functioned more as a kind of intercom device, at first linking the general commissariat to fifteen police stations, and then subsequently being rolled out to all of them. Years later, a second contract signed between the police and the telephone company connected the police to the public network, so that the public could now also phone police stations. The telephone was rapidly perceived as a valuable instrument “in the event of disorders or fires… giving immediate warning signs at those points from which help must come,”16 and correspondingly embodying one of the rationales behind police reform: the emergency response capacity. If it is possible to measure the importance of an aspect of police management by the number and length of the daily orders that were issued, then it is fair to say that the telephone played a major role in police procedure over the period from 1885 to 1895. From just a few of the more comprehensive orders, we can see that these dealt with such issues as: limiting the presence of strangers in the telephone room;17 the need to always have one guard close to the telephone and the importance of the information conveyed;18 reorganizing procedures by incorporating the telephone into instances of fires and medical emergencies.19 The failure to comply with these procedures was also subject to a reprimand by the general commissioner, as, for example, in those cases when stations failed to report cases of suicides, medical emergencies, and instances of serious public disorder.20

The telephone enabled information to circulate more rapidly and thus allowed for faster decision-making. In 1895, when establishing the rules relating to the presence of policemen in the telephone room, the general commissioner also drew attention to the confidential nature of all police information.21 News of threats to public order, more serious crimes or any significant incidents disrupting the routine of the city was thus reported more rapidly to the general commissioner, as well as to other authorities and the government. The telephone did not, however, serve only as an instrument for police surveillance and information gathering. One of the first and most important functions of the telephone was to transmit information about the work of police administration. In December 1880, the first daily order regarding the use of the telephone dealt precisely with organizational issues: what items of uniform should men wear when beginning each shift?22 In subsequent years, failing to promptly convey information via the telephone constituted grounds for the severe punishment of some guards.23 The installation of telephones enhanced the transformation of police stations into central hubs of information at the neighborhood level. The police were able to provide a more systematic coverage of the full extent of the city’s territory and, moreover, to do so in a more cohesive manner.

A Place in the Making

Gradually, policestations became more stable and visible places. One privileged source for understanding this transformation is the almanacs, the directories of the main public and private services available in the city. By the end of the century, these practical city-guides began to contain the addresses, telephone numbers, and names of each station head (Morgado 1895). The development of stations as concrete, physical places is therefore crucial for understanding the notion of proximity and visibility that lay at the core of their raison d’être.

Although they were not as important as city halls or central law courts, police stations also underwent major developments in terms of their architectural form and function. The end of the nineteenth century was marked by a greater volume of public building works, with the architectural styles and interior designs of these new buildings being intended to serve as symbols of civic consciousness and pride and as an indicator of the State’s presence and integration into local communities (Lane 1983; Ewen 2003: 207-240). The aforementioned police reform of 1893 paid special attention to two considerations: visibility and time. In seeking to afford continuation to one particular aspect that had already been contained in the 1876 reform,24 the police reformers stressed the need for police stations to be given greater public visibility, suggesting that each station should display a public sign in its front doorway with the words “Esquadra—Estação,” which was to be illuminated at night with gas lighting. Given that police stations were frequently rented premises, and thus barely distinguishable from the rest of the cityscape, the authorities were concerned about their visibility within the neighborhood; especially when compared with Britain, where the newly constructed police stations were more easily recognized and stood out from the rest of the urban landscape. In Lisbon, however, the most frequent solution was to situate police stations in rented shops, which resulted in the police and the neighborhood being more closely interwoven. Even more significantly, reformers drew attention to the question of time. The 1893 police regulations formally increased the opening hours of the stations, stating clearly that these should be “open permanently, both by day and by night.” This did not mean that stations had not previously been open continuously, but instead it revealed the need to state this formally in the letter of the law. Accessibility was now regarded as a major feature in the planning of new government buildings, being incorporated into the design and physical appearance of police stations (see Image 1).

Image 1 - Police Stations

Source: Ribeiro, Armando (194[?]). Subsídios para a História da Localização das Esquadras da Polícia de Lisboa.Lisbon: Tip. Severo Freitas.

As police stations were generally housed in the ground floors of residential buildings, there was never any discussion regarding their architectural styles or their interior design. Although there is some evidence that, in the 1890s, the premises were refurbished before being opened as police stations in order to comply with certain police requirements. Generally speaking, the different services had to adapt to the space that was afforded by the properties available on the rental market. Some reflections were, however, made about how best to organize the space available inside police stations, with measures being taken to rationalize their use. One of the first tasks was to determine who should or should not be allowed to frequent specific places within police stations and under what conditions such access should be permitted. In October 1881, for example, the General Commissioner emphatically voiced his opposition to the enormous numbers of different people who were to be found in the corridors of the commissariats and police stations. He ordered that this practice should cease, authorizing only policemen or people accompanied by them to circulate on police premises.25 Controlling entry into the station thus became one of the main tasks of the guard stationed at the door, who decided exactly who should or should not be allowed to enter the building. Hence, while it is difficult to note a clear distinction between a public area at the front of the building, to which the general public were allowed access, and a private area, where policemen could socialize, hold detainees, and perform interrogations (Holdaway 1980), this distinction did, in fact, exist and was enforced despite the spatial contingencies.

The routines inside police stations were characterized by a dynamic tension between a disordered and unorganized space, arising from the contingent physical conditions and the concern that was paid to rationalizing space and procedures. Some clearly defined spaces and practices did emerge from this tension. The station chief’s office had already begun to be established within police stations as a particular demarcated space. On several occasions over the years, certain items stated in the daily orders issued directly to station chiefs clearly specified that certain tasks had to be performed in their offices. Notably, this included the lectures given to policemen in order to inculcate the ideal forms of police performance and discipline. However, the growing demand for written information represented another aspect that rendered the chief’s office an identifiable space. These written records included all the information sent to police headquarters and to other authorities, as well as the paperwork directly related with the station’s day-to-day management. The first type of information, for example, included the “daily service schedules,”26 the “fortnightly charts”27 relating to salary payments, the reports of occurrences, and other reports that were compiled about specific issues.28 The second type consisted of copies of the daily orders and other useful information for policemen, or the details of “paid services.”29 Altogether, they turned the chief’s office into a distinct site for the keeping of bureaucratic records. One consequence of the growing bureaucracy involved in police work was the accumulation of paper, which therefore brought filing and storage procedures to police stations. Those papers that had to be kept for later reference were normally stored in the chief’s office. The daily orders are just one example of this requirement. In 1890, the general commissioner reminded station chiefs of the need to take “extreme care” with the ledgers of daily orders, which had to be carefully stored and kept safe in their offices. He finished the order with the threat: “an employee of the general commissariat will shortly be assigned to supervise whether or not this order has been fulfilled.”30

These various writing tasks were not limited to the station chief. In November 1907, Aquilino Ribeiro, by then a radical republican, was arrested after an unintended explosion killed two of his comrades. In his memoirs, he claimed that the police’s “bureaucratic landscape” had become ingrained in his mind after the time that he spent at a police station (Ribeiro 2008: 220). In his description of the police station where he was detained and from where he would escape—a description based on “a careful study of the place and the policemen”— one of the spaces that Ribeiro identified was a room that served as a clerical office. With “two straw chairs and a pinewood table,” it was a central space in the station around which much of the policemen’s everyday life was structured (Ribeiro 2008: 200, 228). This image shows how policemen were increasingly given written tasks to perform, with the daily orders routinely containing instructions on how to fill in forms or write reports. The closure of the commissariat buildings in 1893, which had previously dealt with these written tasks and where painstaking attention had long been paid to both the form and techniques of bureaucracy (Regulamento 1875), meant that these bureaucratic procedures were transferred to the police stations. Furthermore, the police simultaneously stopped hiring civilian clerks to perform the writing tasks. Writing out the notices for fines, compiling maps of occurrences, public health bulletins, details of arrests, and the reporting of crimes were now an important part of the increasingly heavy bureaucratic workload of policemen. These tasks were mainly performed at the police station and led to the development of the policemen’s skills as bureaucratic clerks.

Police stations became increasingly important places, not because they were restricted entirely to policemen but because they were regularly frequented by the local population. Most notably, stations were frequented by individuals who had been arrested. Though detainees did not stay long at the police stations, actual arrests began to take place more frequently at the stations than in the street. The intimate atmosphere of police stations was soon understood to offer a more protected space that was better suited to formally arresting people than the street. Policemen were advised that they should only issue “arrest orders” in the street and that all further inquiries should be completed inside the station.31 The aim was clear: to prevent crowds from surrounding the policeman and the individual, which often tended to trigger even greater conflict. This clearly shows just how the police station increasingly became the central location for interactions between the police and the public.

The population did not use police stations only because they were coerced to do so. Indeed, one essential aspect for understanding the progressive evolution of the meaning of the word esquadra to denote the police station itself was the way in which it was increasingly used by the population as a way of describing the place that they could resort to when they needed help. Eric Monkkonen (2004: 86-109) draws attention to the use of police stations as overnight lodgings for the homeless in urban America. In Lisbon, police stations evolved into places where help might be requested in medical emergencies, for example, and where stretchers were available for the transport of poor people to hospital (Almeida 1959: 53). The prevention of crime, the detection of criminals, and the maintenance of public order represented just a fraction of police work; emergency services also constituted a relevant proportion of police duties. Whether people were requesting a service or complaining about a theft, the dynamics of the police station were clearly affected by the fact that people had recourse tothem on a voluntary basis.

Conclusion

This article has shown how police stations gradually evolved in their organizational procedures as government technologies were translated into concrete processes of territorialization and bureaucratic rationalization. From an organizational point of view, police stations were the cornerstones in the process that transformed police forces into standardized bureaucracies. The adoption of devices such as the telephone and the evolution in bureaucracy turned the police station into the main center of police operations. Contrary to what was to happen in the twentieth century, when such technological devices as the radio and the automobile brought further changes in the relationship between police forces and the surrounding urban space, the need for more intense physical proximity was the main rationale behind the police’s organizational structure. The police station assumed the role of an anchor, becoming a central hub for communication as well as for disciplining and controlling the behavior of policemen.

This only happened after the interiors of police stations evolved into different functional spaces. Even though nothing resembling a standardized design for police stations ever emerged, there were evident demarcations of the internal spaces. The enforcement of rules of access produced a clearer demarcation between the public and private spaces inside the station. The private areas of the stations—spaces such as the chief’s office, the telephone room, and the office used for clerical purposes—were clearly identified according to their respective nature and function. However, this was not only a top-down process. In Portugal, State-building was marked by unstable processes, riddled with political and social resistances and conflicts. As could be seen from the way that the police stations were set up, this ended up being more of a process of negotiation than an imposition upon urban communities. The relationship between the police and the city was marked by a dynamic interaction with other institutions, communities and the rental property market. The public visibility of the police steadily increased due to the fact that the police stations acquired a more stable status, whilst emerging as anchors of the State within urban communities.

References

AAVV (2001). Dicionário da Língua Portuguesa Contemporânea da Academia das Ciências de Lisboa. Lisbon: Verbo, vol. I.

Almeida, Fialho (1959 [1882]). A Cidade do Vício. Lisbon: Livraria Clássica Editora.

Camelo, Hermes (1971). História do Serviço Telefónico do Batalhão de Sapadores Bombeiros. Lisbon: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa.

Emsley, Clive (2007). Crime, Police & Penal Policy: European Experiences, 1750-1940. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Ewen, Shane (2003). Power and administration in two midland cities c. 1870-1938. Leicester: PhD Thesis, U of Leicester.

Figueiredo, Cândido (1911). Novo Diccionário da Língua Portuguesa. Lisbon: Portugal-Brasil Limitada, vol. I.

Gonçalves, Gonçalo Rocha (2012). Civilizing the police(man): police reform, culture and practice in Lisbon, c. 1860-1910. Milton Keynes: Open University, Unpublished PhD Thesis.

Gonçalves, Gonçalo Rocha (2014). Police reform and the transnational circulation of police models: The Portuguese case in the 1860s. Crime, Histoire & Sociétés / Crime, History & Societies, 18(1): 5-29.

Gonçalves, Gonçalo Rocha (2015). O aparelho policial e a construção do Estado em Portugal, c. 1870-1900. Análise Social, L, 3º (216): 470-493.

Gonçalves, Gonçalo Rocha (2016). Biografias transnacionais, cosmopolitismo e modernidade urbana: Cristóvão Morais Sarmento e a polícia portuguesa no final do século XIX. Iberoamericana. América Latina – España – Portugal, vol. 16, Nº 64.

Holdaway, Simon (1980). The Police Station. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 79: 79-100.

Lane, Barbara (1983). Government Buildings in European Capitals, 1870-1914. In J. Teuteberg (ed.), Urbanisierung im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert: Historische und geographische aspekte. Cologne, Böhlau, 517-560.

Machado, José P. (1977). Dicionário Etimológico da Língua Portuguesa. Lisbon: Livros Horizonte, vol. II.

Monkkonen, Eric (2004). Police in Urban America, 1860-1920. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004.

Morgado, Alexandre (1895). Guia do Forasteiro nas Festas Antonianas. Lisbon: Typ. Comércio.

Palácios Cerezales, Diego (2011). Portugal à Coronhada: Protesto Popular e Ordem Pública nos séculos XIX e XX. Lisbon: Tinta da China.

Regulamento das Secretarias do Comissariado Geral e das Divisões da Polícia de Lisboa (1875). Lisbon: Typographia Universal.

Ribeiro, Aquilino (2008 [1972]). Um escritor confessa-se. Lisbon: Bertrand.

Santos, Maria José Moutinho Santos (2001). Bonfim – Séc. XIX: a regedoria na segurança urbana. Cadernos do Bonfim, vol. 1, 1-25.

Silva, Álvaro Ferreira da (1997). Crescimento Urbano, Regulação e Oportunidades Empresariais: A construção residencial em Lisboa, 1860-1930. Florence: European University Institute, Unpublished PhD Thesis.

Silva, António M. (1877). Diccionário da Lingua Portuguesa. Lisbon: Typographia Joaquim Germano de Souza Neves, vol. I.

Silva, António M. (1890). Diccionário da Língua Portuguesa. Lisbon: Empresa Literária Fluminense, vol. I.

Staeheli, Lynn A. (2003). Place. In John Agnew et al (eds.), A Companion to Political Geography. Malden, MA, Blackwell, 158-170.

Tarr, Joel (1992). The municipal telegraph network: origins of the fire and police alarm systems in American cities. Flux, 9: 5-18.

Williams, Chris A. (2014). Police Control Systems in Britain, 1775-1975. Manchester: Manchester UP.

Notes

1 Department of History. Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected]

2 We follow here the concept of ‘place’ as used in the field of human geography, which defines ‘place’ as “a context or setting, in relational terms, as an outcome or product of processes, and as something active and dynamic” (Staeheli. 2003: 159).

3 Portuguese National Archives / Archive of the Ministry of the Interior [IAN/TT-MR], [Maço] Mç.3015, Livro [Lº] 14, Number [Nº] 375.

4 IAN/TT-MR, Mç.3023, Lº14, Nº1325.

5 IAN/TT-MR, Mç.3021, Lº14, Nº1039.

6 IAN/TT-MR, Mç.3071, Lº19, Nº581.

7 IAN/TT-MR, Mç.3015, Lº14, Nº333.

8 IAN/TT-MR, Liv.1686-A, fl.5-8, 56-57.

9 IAN/TT-MR, Mç.3025, Lº14, Nº1794.

10 IAN/TT-MR, Mç.2981, Lº12, Nº701.

11 IAN/TT-MR, Mç.3023, Lº14, Nº1440.

12 IAN/TT-MR, Mç.2837, Lº37, Nº344.

13 IAN/TT-MR, Mç.3007, Lº12, Nº2042.

14 Diário de Lisboa, Nº167, 29-07-1867.

15 Portuguese National Archives, Archive of the Polícia Civil de Lisboa, Transfer Number [NT] 215 Provisional Number [NP]077, Daily Order [DO] Number.[N.] 296, 22-10-1876, Point [P.]1.

16 Comércio do Porto, 02-07-1882.

17 NT219 NP082, DO N.13, 13-01-1885, P.4.

18 NT219 NP082, DO N.202, 21-07-1885, P.8.

19 NT225 NP087, DO N.315, 11-11-1889, P.6.

20 NT229 NP091, DO N.330, 25-11-1892, P.5.

21 NT230 NP092, DO N.13, 13-01-1895, P.1.

22 NT218 NP081, DO N.344, 09-12-1880, P.6.

23 NT220 NP083, DO N.340, 06-12-1885, P.4.

24 Regulamento dos Corpos de Polícia Civil (21-12-1876), Diário do Governo, Nº 295, 30-12-1876, Capítulo IV, Artigo 27º.

25 NT218 NP081, DO N.289, 16-10-1881, P.4.

26 NT213 NP075, DO N.295, 22-10-1873, P.1.

27 NT213 NP075, DO N.297, 24-10-1873, P.1.

28 NT223 NP086, DO N.197, 15-07-1888, P.7.

29 NT229 NP091, DO N.254, 11-09-1893, N.6.

30 NT225 NP087, DO N.281, 08-10-1890, P.10.

31 NT218 NP081, DO N.289, 16-10-1881, N.5.

Received for publication: 11 November 2015

Accepted in revised form: 20 January 2017

Recebido para publicação: 11 de Novembro de 2015

Aceite após revisão: 20 de Janeiro de 2017

Copyright

2017, ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH, Vol. 15, number 2, December 2017