|

|

The Cost of Graduation and Academic Rituals: Material Expressions of Student Life in the Late Middle Ages in Portugal1

Armando Norte2

Rui Miguel Rocha3

Abstract

Medieval universities were always institutions where certain rituals were regularly performed in varying forms and at different places and moments. Such practices have also been identified as taking place at the Portuguese University, where they marked important moments in a student’s life, involving, for example, processions or graduation ceremonies. These were solemn events displaying a strong urban identity, which followed routes that passed by important and symbolic places in the city (cathedrals, churches, public squares, etc.), often complemented by the celebration of religious masses and sermons. The aim of this paper is to reconstruct the urban itineraries followed by the members of universities and the costs and revenues involved in these acts, as expressed in the university statutes issued by King Manuel I (c. 1503).

Keywords

Middle Ages; Portuguese University; academic rituals; university finance; urban space.

Resumo

A universidade foi sempre uma instituição fortemente ritualizada nas suas práticas, expressas em diferentes formas, espaços e momentos do quotidiano académico. Assinalavam momentos marcantes da vida estudantil, como a concessão de graus ou a realização de procissões, com passagens por lugares importantes e simbólicos da cidade (sé, igrejas, praças públicas, etc.), complementadas por missas e pregações. Tal apropriação do espaço citadino pelos escolares é identificável nas fontes documentais, nomeadamente nos estatutos universitários ordenados pelo rei D. Manuel I (c. 1503). O objetivo deste artigo é reconstituir os itinerários urbanos estudantis e as práticas económicas e financeiras que lhes estavam associadas.

Palavras-chave

Idade Média; Universidade portuguesa; Rituais académicos; Finanças universitárias; Espaço urbano.

Medieval universities were, in essence, a typically urban phenomenon (Le Goff 1957: 9-14). The city was, in fact, a decisive factor behind their origin—as universities were the successors of cathedral schools (Frova 1995: 332)—as well as determining their institutional characterization (Verger 1992: 48). This penetration into and appropriation of the city by scholars, together with the numerous privileges granted by the competent authorities inevitably led to great tension between the various university members—teachers, students, and officials (Marques 1997: 69-127)—and the populations of the cities where these emerging institutions were established. This was the case, for example, of the pioneering generalia of Bologna, Paris, and Oxford (Kibre 1961), a phenomenon that historiography commonly describes as town and gown (Brockliss 2000). Lying at the root of these conflicts were not only the numerous privileges granted by kings, popes, and municipalities (Nardi 1992: 77-107), but also the bohemian lifestyle of many of the scholars (Schwinges 1992: 195-243). There were also several violent intellectual debates that were responsible for several bloody confrontations, the most important of which was the one that affected the University of Paris in the thirteenth century (Heer 1998), pitting the Faculty of Arts against the Faculty of Theology over the reintroduction in the West of the lost works of Aristotle, known by the generic name of Logica Nova (Lohr 1982).

Naturally, the close connection between medieval universities and cities also manifested itself in a peaceful way, which was in fact the most common and visible aspect of this relationship, as far as we can glean from what is known about student life in the Middle Ages (Moulin 1991). Obviously, these links were reflected at an architectural level, with the construction of school buildings (Lobo 2010), and certainly at an economic level, with the creation of colleges (Bartolomé Martínez 1995: 326-373), the concession of specific housing districts for scholars (Schwinges 1992: 213-222), and, finally, the activity of the university and its members as economic actors themselves (Gieysztor 1992: 108-143). Yet it was also visible in the frequent and large-scale public rituals and ceremonies typical of university institutions. Indeed, these rituals were sometimes very elaborate affairs (Chiffoleau, Martines, and Bagliani 1994), taking the form of processions, religious masses, and sermons (Destemberg 2010: 337-341), as well as other academic acts, such as graduation ceremonies (Destemberg 2009: 113-132), which will be analyzed later on. These occasions involved a wide diversity of different features, such as parades, banquets, and the mandatory wearing of scholarly garments and insignia, among others (Veloso 1997: 149-151).

In fact, not unlike its medieval counterparts in other countries, the Portuguese University always had an ambiguous relationship with the cities (Lisbon and Coimbra) that hosted it throughout the period under study here (Mattoso 1994: 23-35), clearly visible in the interaction between the university bodies and the urban powers (Coelho 2007: 309-326), and especially between the students and the local communities (Norte and Leitão 2018: 513-527). At times symbiotic, these relationships very often seem to have been rather disruptive, to the point where they caused some of the numerous relocations of the Portuguese studium generale. On occasions, this situation was even mentioned explicitly in the historical documentation, as for example in the bull of Pope Clement V, which clearly refers to the “grauiam dissemtiones et scandala” (severe disputes and scandals) provoked by scholars (Moreira de Sá 1966: 41–42).

The more peaceful appropriation of the city by scholars, which obviously displayed its own symbolic and material aspects, is also clearly identifiable in medieval documentation, namely in the university statutes issued by King Manuel I presumably at the beginning of the sixteenth century. These statutes were designed to reform Portuguese University, which at that time were under the tutelage of the Archive of the University of Coimbra (Dom Manuel I 1503). In this paper, reference will be made to the most recent edition of this source, published together with the statutes of other universities by Manuel Augusto Rodrigues (Rodrigues 1991: 29–41). These are only the third set of regulations relating to the Portuguese studium generale known to be in existence, but they are certainly the most complete of the three. We can find in them a great deal of information about the day-to-day life of the institution, making it possible to reconstruct the students’ urban itineraries and the concrete practices associated with them, as well as their economic repercussions for the university, its members, and other institutional agents.

Besides the relevance of this economic approach, it is important to highlight the almost complete absence in the Portuguese historiography of any comprehensive and specialized studies about academic rituals (in contrast to the attention that has been given to this topic internationally). In the Portuguese case, the notable exceptions are Teresa Veloso’s essay about the Middle Ages (Veloso 1997) and the monograph by Armando Carvalho Homem about contemporary practices, with its heavy emphasis on academic garments (Carvalho Homem 2006).

The date of publication of the statutes is linked to the fourth relocation of the Portuguese University, after its foundation at the end of the thirteenth century by King Dinis (Sousa Costa 1991: 71-82), which often traveled back and forth between the cities of Lisbon (1290-1308; 1338-1354; 1377-1537) and Coimbra (1308-1338; 1354-1377) during the Middle Ages, this being a unique feature among European medieval universities of this period (Dias 1997: 33). In fact, the statutes correspond to a time when the university was located in Lisbon (Martins 2013: 41-88), which is why this article will focus on this geographical area, already the capital of the kingdom at this time (Oliveira Marques 1988: 80-91).

Academic Rituals

As stated before, academic rituals were an important part of the academic year and we can find evidence of this in the source, as most of them are described in a detailed manner, in close connection with the urban space. These events, sometimes involving ecclesiastical rites, included: the public reading of statutes (Rodrigues 1991: 30); elections of academic bodies (Rodrigues 1991: 32); funerals of scholars (Rodrigues 1991: 33); daily masses before lectures (Rodrigues 1991: 33); legal hearings under academic jurisdiction (Rodrigues 1991: 35); processions, sermons, and solemn masses on festive days (Rodrigues 1991: 33–34); and graduation ceremonies (Rodrigues 1991: 36–38). Due to the quantity and quality of the available data and the importance of such acts in the everyday life of the academy, this paper will focus only on the last two of these activities: processions and graduation ceremonies.

All these public practices had to comply with an assortment of regulations, with the different events being framed by the academic year, starting on October 19 (the day after St. Luke’s Feast Day)— symbolically marked by the delivery of an inaugural speech by highly regarded scholars, such as Pedro de Meneses (Pedro de Meneses 1504), André de Resende (André de Resende 1534), and Jerónimo Cardoso (Jerónimo Cardoso 1536)—and ending on August 15 (the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary). Many of these special moments in academic life were punctuated by the holy days of the liturgical calendar. All the public ceremonies had to be announced previously and all members of the academy were required to be present at such acts, which could not take place on school days (Rodrigues 1991: 31). Furthermore, the wearing of academic dress was compulsory at all ceremonies (Rodrigues 1991: 39).

Academic Processions

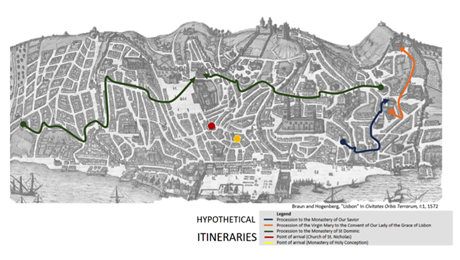

As far as the first group of academic rituals is concerned—processions, together with sermons and solemn masses—there were five events mentioned in the regulations that took place on the Lisbon city streets: the procession to the Monastery of Our Savior, a convent of Dominican nuns, which took place on December 25; the procession of the Virgin Mary to the Convent of Our Lady of Grace, of the order of the Hermit Friars of Saint Augustine, which took place on March 25; the biannual procession to the Monastery of St Dominic; the procession to the Parish Church of St. Nicholas; and, finally, the procession to the Monastery of Our Lady of the Conception, affiliated with the Portuguese military Order of Christ, all of which took place on non-stipulated dates (Rodrigues 1991: 33-34). All these public ceremonies organized by the university were governed by a series of rules. The unjustified absence of bachelors was punishable with a fine of three gold doubloons, paid to the university treasury. Certain formal procedures also had to be honored—university members were compelled to wear full academic dress and had to organize themselves into pairs in order to participate in the acts while the teachers of grammar and logic, equipped with red poles (academic insignia), were in charge of leading all processions (Rodrigues 1991: 34).

The map shows the itineraries of the academic processions all around the city as accurately as possible (see Figure 1). For instance, we can clearly see the points of arrival for some of the processions and the points of both departure and arrival of others. Only the itineraries themselves are hypothetical, although three variables were taken into consideration in their design—the wider routes, the distance covered by the procession, and the city’s topography. It should be noted that the map shown here dates from the late sixteenth century, which is not very far removed from our timeframe, meaning that this is the most accurate depiction of the city at the time and the most suitable for our purpose. It is part of the large collection of maps assembled in the work known as Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Braun and Hogenberg 1572).

Figure 1: Academic Processions

All five events are described in the source. The first relates to the annual Christmas Day procession to the Monastery of Our Savior (Rodrigues 1991: 33), celebrating the donation of school buildings to the university by Prince Henry, its former protector, in 1431 (Moreira de Sá 1974: 177–78). The procession was followed by a mass conducted by the theology teacher. Teachers and students were each required to pay 10 reais to the sisterhood of the monastery, as well as 100 reais to the other monasteries in attendance, with the payment of the full amount being shared between all the contributors (Rodrigues 1991: 33). The information found in the source enables us to attempt to establish a hypothetical, yet quite probable, itinerary for the procession. Even so, the point of arrival is beyond dispute. There are some doubts about the point of departure as the name of the church mentioned in the document is ambiguous, since São Gião could refer to the church of both São João (St. John) and São Julião (St. Julian). We believe that the document refers to the church of St. John as this was located close to the students’ quarter and to the university itself. Furthermore, it is quite interesting to note that the final destination of the procession—the church of Our Savior—was adjacent to the university. Considering all these aspects, the most probable route was through St. Peter’s Gate, passing through the students’ quarter and in front of the studium building until finally reaching the church. All of this means that we are able to claim with some confidence that every Christmas Day in the early sixteenth century, students and teachers would go to the Monastery of Our Savior where they would attend the mass celebrated by the theology teacher.

As for the second procession, this would take place on Saint Mary’s Day (March 25), followed by a solemn mass (Rodrigues 1991: 33). Like the previous one, it was presided over by the Chair of Theology and it was meant to celebrate the donation of houses to the university in 1431 (Moreira de Sá 1972: 59–61). According to the document of donation signed by Prince Henry, the procession was supposed to start at the university buildings (Moreira de Sá 1970: 28–30) and finish at the Convent of Our Lady of Grace of Lisbon, of the Order of the Hermit Friars of Saint Augustine (Moreira de Sá 1970: 28–30; 1972: 59–61; 1974: 177–78). As far as the costs of this particular procession were concerned, the church would be presented with 100 reais, two candles, and one pound and one ounce of incense, all at the expense of university funds. The rules were strict and could not be neglected by the friars, or else they would be punished (Moreira de Sá 1970: 28–30).

In the case of the other three processions, the references are quite scanty. As far as the Monastery of St. Dominic of Lisbon of the Order of Preachers was concerned, the regulations prescribed two annual processions with different itineraries, to be followed by homilies (Rodrigues 1991: 33–34). Although there is no indication of the dates when these processions took place, it is quite likely that they were connected in some way to the patron saints of the churches mentioned as places of passage in the description of the occasions: St. Catherine of Lisbon and St. Thomas Aquinas (the latter probably being a reference to the parish church of St. Thomas of Lisbon, also a patron of the university). If so, the processions probably occurred on the feast days of these two saints, November 25 and March 7, according to the liturgical calendar prior to the Reformation of the Council of Trent.

As far as the routes taken by the fourth and fifth processions are concerned, the only available information relates to the place of arrival: the parish church of St. Nicholas, the ancient Bishop of Myra in the fourth century, also known as the Bishop of Bari, and the Monastery of Our Lady of the Conception of the Military Order of Christ (Rodrigues 1991: 33-34). Again, it is possible to extrapolate the dates of such events by using the Catholic liturgical calendar, which places them on December 6 and August 15, which was the last day of the academic year. In these cases, the statutes clearly indicate the priests who would be responsible for conducting the masses celebrated after the processions. The teacher of natural philosophy, or a person of his choice if he were unavailable, would officiate at the Church of St. Nicholas; and the teacher of moral philosophy (or metaphysics) would deliver the homily at the Templar Monastery, which ended with a high mass. Some financial reports can also be found relating to this last procession. The king himself offered a total amount of 4,000 reais for the celebration of this occasion. A sum of 3,000 reais was destined for the payment of the priest and 1,000 reais were allocated asfollows: one cruzado—roughly equivalent to 400 reais (Ferreira 2014: 39)—for the mass and for the purchase of candles and incense, with the remainder being given to the university treasury (Rodrigues 1991: 33–34).

Some facts concerning the above-mentioned events could help to explain why those specific ecclesiastical houses were chosen and not others, since the landmarks used in academic processions were not chosen randomly. Firstly, it is possible to explain the two annual pilgrimages made to the Church of St. Dominic in Lisbon because of the predominant position enjoyed by the Dominican Order in the spiritual order of the kingdom from the fourteenth to the early sixteenth century, a situation that was commonly found in the Christian world in general. On the other hand, the procession to the Monastery of Our Lady of the Conception of the Templar friars can be easily explained by the fact that Prince Henry and King Manuel I were both governors of the Order of Christ (Silva 2002). This Order of Christ was the successor of the previous Order of the Temple, which had been suppressed by Pope Clement V in an Apostolic Decree, the bull Vox in Excelso, issued on March 22, 1312 (Demurger 1989: 320). As for the choice of the collegiate churches of St. Nicholas and St. Thomas, both under the king’s patronage, this may well be explained by their links to the funding of the university during the fifteenth century. Thus, the Church of St. Thomas had already been assigned to the studium generale before December 10, 1414 (Moreira de Sá 1969: 71–78), and the Church of St. Nicholas since May 17, 1430 (Moreira de Sá 1969: 395–96). In turn, the significant role played by Prince Henry the Navigator as a former protector of the universityin its improvement at numerous levels, including in material terms (Moreira de Sá 1960), was the reason stated for the processions to the Monastery of Our Savior and to the Convent of Our Lady of Grace of Lisbon (Rodrigues 1991: 33).

In general, it is important to highlight certain aspects relating to the revenues and expenses of the formal acts considered here. It is possible to identify three entities that received payments—the priests responsible for the liturgies, the university itself, and some monasteries—which were paid both in kind and in cash. Firstly, as mentioned earlier, in the case of the priests, the most prestigious teacher of theology and the teachers of natural and moral philosophy were responsible for conducting the solemn masses, for which they received important sums in cash. Secondly, the treasury of the university received payments in cash from the king in order to fulfill his processional wishes. Similarly, the absence of the bachelors who had graduated from the Portuguese University resulted in a fine paid by the offenders to the university treasury. Thirdly and finally, for numerous reasons, some monasteries received donations, in some cases contingent on the presence of representatives of those monasteries. These donations could also be made either in cash or in kind, with the latter donations usually being associated with the liturgical rites (for example, in the form of candles and incense) granted by the king, the university, and individually by its teachers and students (Rodrigues 1991: 33-34).

Graduation Ceremonies

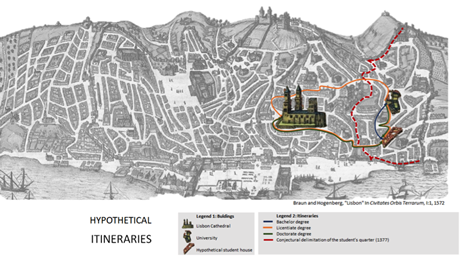

The other academic rituals to be considered in this analysis are the graduation ceremonies (see Figure 2). We can very briefly identify three different types of academic degrees, as was also the case at other similar institutions all over Europe in the same period: the bachelor’s degree, the licentiateship, and the doctorate (Frijhoff 1992: 358).

Figure 2: Academic Graduations

Since they were considered to be public acts, all these academic ceremonies followed a strict protocol, namely with regard to seating arrangements and the dress code. At all ceremonies, the chancellor (inherently the teacher in charge of the Chair of Civil Law) would be seated in the middle, with the rector to his right, while the other participants were distributed on either side of the altar (Rodrigues 1991: 39) according to what was considered the hierarchy of knowledge in medieval times (Le Goff 1957: 83-85). Therefore, the doctors of theology, the doctors of canon law, the doctors of civil law, the masters of medicine, and the masters of liberal arts would be seated in keeping with their decreasing order of hierarchy. They would be duly identified by the color of their tassels: white for theologians, green for canon lawyers, red for civil lawyers, yellow for physicians, and blue for artists. In each faculty, the professors would sit at the front, and behind them the graduates in order of seniority. If any of the king’s magistrates (desembargadores) attended these acts, they would be seated immediately to the rector’s left, regardless of the nature of their academic degree, or even their lack of one. The university’s administrative staff and counsellors would be seated separately from the other members of the academy (Rodrigues 1991: 39).

Nevertheless, despite these general prescriptions, each degree ceremony had its own specific rules and guidelines, for example, in relation to the costs involved and the itineraries that were followed. The least important of the three, the bachelor’s degree, was understandably the cheapest and least complex. Under such circumstances, the itinerary established by the statutes for the ceremony would be drawn between the candidate’s house, if this was located in the students’ quarter (a specific area of the city assigned to the university and its members) and the university buildings. This particular graduation ceremony began when the university members, led by the rector and the beadle with his distinctive pole, set off in the direction of the scholar’s home in order to collect him. They would then all return together in a procession to the university where the graduation examination would be carried out (Rodrigues 1991: 36). Prior to the lecture and its ensuing discussion—the two parts of which the examination consisted, as dictated by the scholastic formula (Bonfil 2004: 179-210)—an opening address would be given by the candidate. After the examination was completed, the student would request his degree by giving a closing speech, immediately followed by the offering of specific gifts to certain academic members and by the graduation oath addressed to the beadle. The ritual would end with the award of the bachelor’s degree by a doctor or a master, depending on the subject that was examined, followed by a blessing addressed to God and to the entire audience. The award of the degree implied the offer of a pair of gloves and a cap to the sponsor, gloves to the rector and the teachers who attended the graduation ceremony, one gold doubloon to the beadle, and, finally, one gold doubloon, together with fine fabrics, to the university (Rodrigues 1991: 36).

In the case of the licentiateship, several important differences can be noted. For instance, the graduation ceremony was centered around three places instead of just two: the candidate’s home, in the students’ quarter; the university buildings; and Lisbon Cathedral, where the licentiate would take his oaths and complete his graduation examination. All of these places were contained within the eastern area of Lisbon (Rodrigues 1991: 36–37). For the sake of convenience, although we cannot precisely identify a candidate’s home, we chose a location where there would probably be houses used for student residence according to the delimitation of the university residential quarter established by King Fernando (Moreira de Sá 1968: 5–9), one of the predecessors of King Manuel I. Moreover, these acts were considered to be highly important, as can be seen from the full participation of all the members of the university in them, albeit not always at the same phase of the examination. As far as the different stages of the examination ritual were concerned, as defined by the statutes, the examination was scheduled to take place over a particular period of time, and then, on the morning of the first day, the bachelor would meet his friends, sponsor, and beadle at the university and they would go together to Lisbon Cathedral to attend the mass of the Holy Spirit. Afterwards, the chancellor and the sponsor would have a meeting, probably inside the cathedral, to decide upon the lessons that the candidate should read for the examination. The bachelor would then go back to his home alone and study for two days. During that period, the candidate had to send one measure of white wine, one measure of red wine, and a chicken to the examiners, rector, and beadle and twice that amount of food and drink to the sponsor and chancellor. Besides the above-mentioned expenses, the graduate had to pay three gold doubloons plus 2000 reais to the university treasury or else offer fabrics in their place to the beadle. After the two days had elapsed, all the members of the university, suitably clad in academic dress, would come to his house to collect him. Then they would proceed with torches in an orderly fashion to the cathedral again where the examination would finally take place at sundown. Once it was completed, the bachelor and his friends would go back to his home and wait for the results. In the meantime, the examiners (and the beadle for bureaucratic purposes) stayed in the cathedral to either approve or fail the candidate. After making their decision, they would send a messenger to the bachelor's house to announce their verdict (Rodrigues 1991: 36–37).

In the case of the doctorate (applicable to students of theology, canon law, and civil law) and the master’s degree (applicable to students of medicine and liberal arts), the procedures were similar to those followed for the licentiateship. As in the previous situation, the candidates were escorted from their houses to the city’s cathedral by the doctors and masters and all the members of the university who wished to honor them, in order to attend the morning mass of the Holy Spirit. A dress code was imposed on the participants and specifically on the candidate, who was required to wear appropriate academic dress (still without a cap), or, in the case of friars, their habits. They also had to consider the previously described hierarchical rules of precedence for public acts in the examination room, with the candidate being seated opposite the chancellor on a lower seat at a table, accompanied by two bachelors or licentiates. From that seat, he would begin his examination by reading a brief lesson, which would then be discussed by the rector and by some chosen members of the candidate’s faculty. After this, the candidate would offer a considerable number of gifts—gloves to all the bachelors and noblemen as well as caps to the chancellor, sponsor, licentiates, doctors, and university officials. As part of the ritual, an honorable man was appointed to praise the candidate’s virtues in Latin while also underlining some minor flaws in Portuguese. A pledge would be made to the scribe afterwards, followed by a speech made by the examinee himself, requesting the concession of the degree from his sponsor, who would ultimately award him the degree and the corresponding insignia (a ring and a cap with a tassel), ending with a symbolic kiss on the candidate’s face. To complete the ritual, all the university members would have dinner together at the expense of the newly-appointed graduate. The exception was the liberal arts master, whose sole obligation was to provide a meal to the graduates. Just as was the case with the bachelor and licentiate degrees, the candidate was obliged to pay fees in order to obtain a doctorate. Under these circumstances, the applicant for a doctorate would pay five gold doubloons to the university and 3,000 reais to the beadle as a reminder of the tradition of dressing this official properly in accordance with the old statutes (Rodrigues 1991: 38).

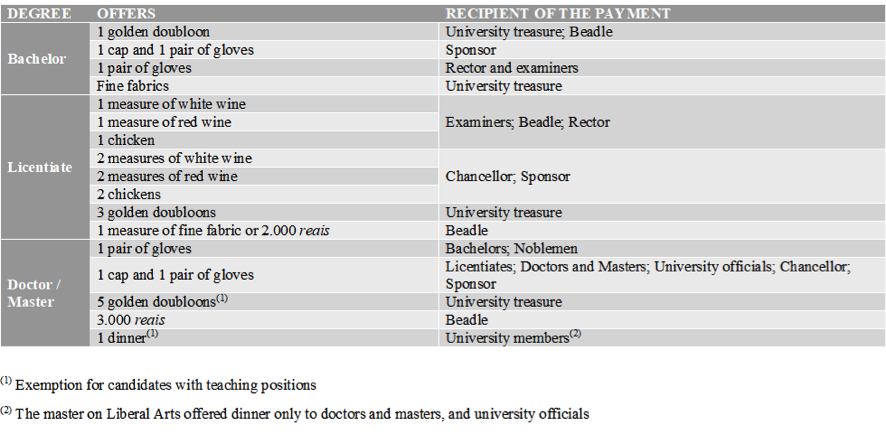

Some remarks should be made regarding the gifts made by the candidates in the context of the three graduation ceremonies (see Table 1).

Table 1: Offers by the Candidates vs type of Degrees and Recipients of the payment

First of all, the expenses were proportional to the hierarchical level of the degree, with the candidates for a bachelor’s degree being the least overburdened with costs, while those applying for doctorates had the greatest expenses. This can be easily understood as the candidates for a doctorate had to benefit all those taking part in the public act, with no exceptions being made, while the bachelor and the licentiate were exempted from having to offer gifts to undergraduates and noblemen. Furthermore, the amount paid to the university treasury differed substantially among the candidates: those applying for a bachelor’s degree paid only ⅕ of the amount paid by those applying for a doctorate and ⅓ of the amount paid by those applying for a licentiateship. In turn, we can find different levels among the beneficiaries at the ceremonies—the university officials (mainly the rector, the beadle, and the chancellor), the examiners, and the sponsors were quite often offered gifts by the candidates and only rarely were gifts made to graduates and noblemen.

According to the statutes, most of the tributes were paid in kind, albeit with some exceptions. The most important of these was the university, which almost always received monetary payments. Apart from the university treasurer, only one of the officials of the studium generale, namely the beadle, received monetary payments, as he was the main administrative agent. The money could be paid either in gold doubloons or in reais. As far as the payments in kind were concerned, we can note some differences since we can find records relating to gifts of academic garments (namely gloves and caps), fine fabrics, and food, such as chickens, red and white wine, and full meals.

The items most frequently offered by the candidates, with the exception of the licentiates, were academic garments, once again consisting of gloves and caps. In contrast, the offer of full meals (dinners) was an exclusive obligation of the candidates applying for doctorates. Yet, although licentiates were not obliged to pay for full meals, the statutes required the presentation of some agricultural products. As far as the gifts of food were concerned, candidates applying for bachelor’s degrees had no obligations whatsoever.

Final Remarks

Considering all that has been said above, some main conclusions can be drawn. In the first place, due to the sheer quantity and quality of the data, the statutes are a reliable, useful, and fertile source for the study of academic rituals and their associated expenses. Also, among the academic rituals described, there was a clear emphasis on processions and graduation ceremonies, governed either by general or specific regulations.

Furthermore, the public acts of the Portuguese academy must be understood in the light of the general characteristics of medieval universities, such as their heavily ecclesiastical dimension. Yet, there were also some specific features in the case of the Portuguese University: its royal tutelage, the policies of its protectors, and, most probably, its funding strategies. The liturgical calendar was also of major importance for the scheduling of the academic year. These circumstances also seem to have influenced the choice of specific ecclesiastical houses for the performance of academic public acts.

Additionally, most academic itineraries, specifically those followed in the graduation rituals, were confined to a clearly circumscribed area of the city. This perimeter was located in the eastern side of the city landscape, within a triangle formed by the university buildings, the city cathedral and the students’ quarter.

Moreover, in financial terms, most of the expenses involved in processional acts were related to the payment of priests (invariably a university teacher), the endowment of ecclesiastical houses, and contributions to the university treasury. Among the contributors, we can identify the king himself, scholars, and the university (acting both as a contributor and a recipient). These payments could be made either in cash or in kind, but, in the latter case, they took the form of liturgical implements.

Finally, in the graduation ceremonies the costs were borne entirely by the candidates, being paid in proportion to the importance of the degree. Whether receiving payments in cash or in kind, the beneficiaries were mainly the university officers, the sponsors, and the examiners, as well as the university itself, which mostly received cash payments. The payments in kind were quite diverse, including clothing, fine fabrics, and food.

To sum up, academic rituals played an important symbolic (and, by extension, financial) role in the medieval Portuguese University, as was the case all over the Christian world. This was clearly visible in the need felt by King Manuel I to put many of the rules for these ceremonies into writing. These rituals and solemnities would necessarily have a notable impact on the city’s landscape, where the most important moments of the academy’s life were displayed. In the precise itineraries of these processions, which took place in the city’s main streets and squares, the university presented itself as a strongly cohesive group, quite distinct from the rest of the society.

References

Bartolomé Martínez, Bernabé (1995). “Las universidades medievales, los primeros colegios universitarios.” In Bernabé Bartolomé Martínez (ed.), Historia de la acción educadora de la Iglesia en España. Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, vol. 1, 326–73.

Bonfil, Robert (2004). “El modelo escolástico de la lectura.” In Roger Chartier, Jacqueline Hamesse (eds.), Historia de la lectura en el mundo ocidental. Madrid: Taurus Ediciones, 179-210.

Braun and Hogenberg (1572). Lisbon. Civitates Orbis Terrarum.

http://historic-cities.huji.ac.il/portugal/lisbon/maps/braun_hogenberg_I_1_1.html.

Brockliss, Laurence (2000). Gown and Town: The University and the City in Europe, 1200–2000. Minerva, 38 (2) : 147–70.

Cardoso, Jerónimo (1536) 1965. Oração de Sapiência proferida em louvor de todas as disciplinas. Lisbon: Instituto de Alta Cultura.

Carvalho Homem, Armando (2006). O traje dos lentes: memória para a história da veste dos universitários portugueses (séculos XIX-XX). Porto: Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto.

Chiffoleau, Jacques; Martines, Lauro; and Bagliani, Agostino Paravicini (eds.) (1994). Riti e rituali nelle società medievali. Spoleto: Centro italiano di studi sull’alto medioevo.

Coelho, Maria Helena da Cruz (2007). “Coimbra et l’université: complémentarités et oppositions.” In Les universités et la ville au Moyen Âge: Cohabitation et tension. Leiden: Brill, 309–26.

Demurger, Alain (1989). Vie et mort de l'Ordre du Temple: 1118-1314. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Destemberg, Antoine (2009). Un système rituel? Rites d’intégration et passages de grades dans le système universitaire médiéval (XIIIe-XVe siècle). Cahiers de Recherches Medievales, 18 (1): 113–32.

Destemberg, Antoine (2010). “Autorité intellectuelle et déambulations rituelles: les processions universitaires parisiennes (XIVe-XVe siècle).” In Des sociétés en mouvement. Migrations et mobilité au Moyen-Âge. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 337-41.

Dias, Pedro (1997). “Espaços escolares.” In História da Universidade em Portugal: 1290-1536. Coimbra—Lisbon: Universidade de Coimbra—Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, vol. 1 (1), 33-8.

Ferreira, Sérgio (2014). Preços, salários e níveis de vida em Portugal na baixa idade média. Porto: Universidade do Porto. PhD Thesis.

Frijhoff, Willem (1992). “Graduation and careers.” In Hilde de Ridder-Symoens (ed.), A History of the University of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 2, 355-415.

Frova, Carla (1995). “Scuole e università.” In Guglielmo Cavallo, Claudio Leonardi, and Enrico Menestò (eds.), Lo spazio letterario del Medioevo. Il Medioevo latino. Rome: Salerno Editrice, vol. 2, 331–60.

Gieysztor, Aleksander (1992). “Management and resources.” In Hilde de Ridder-Symoens (ed.), A History of the University of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 1, 108-43.

Gilli, Patrick; Verger, Jacques; Le Blévec, Daniel (eds.) (2007). Les universités et la ville au Moyen Âge: cohabitation et tension. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

Heer, Friedrich (1998). “The Medieval World: Europe 1100-1350.” In Intellectual Warfare in Paris. London: Phoenix, 213–26.

Kibre, Pearl (1961). Scholarly privileges in the Middle Ages: the rights, privileges and immunities of scholars and universities at Bologna, Padua, Paris and Oxford. London: Medieval Academy of America.

Le Goff, Jacques (1957). Les intellectuels au Moyen Âge. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Lobo, Rui (2010). A universidade na cidade. Urbanismo e arquitectura universitários na Península Ibérica da Idade Média e da primeira Idade Moderna. Coimbra: Universidade de Coimbra. PhD Thesis.

Lohr, C. H. (1982). “The Medieval Interpretation of Aristotle.” In Norman Kretzmann, Anthony Kenny, and Jan Pinborg (eds.), The Cambridge History of Later Medieval Philosophy: From the Rediscovery of Aristotle to the Disintegration of Scholasticism 1100-1600. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 80–98.

Manuel I (D.) 1503. Estatutos de D. Manuel I. AUC- V-3.a- Cofre - n.o 16. Arquivo da Universidade de Coimbra. https://pesquisa.auc.uc.pt/details?id=272468.

Marques, José (1997). “Os corpos académicos e os servidores.” In História da Universidade em Portugal: 1290-1536. Coimbra—Lisbon: Universidade de Coimbra—Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, vol. 1 (1), 69-127.

Martins, Armando Alberto (2013). “Lisboa, a cidade e o Estudo: a Universidade de Lisboa no primeiro século da sua existência.” In Hermenegildo Fernandes (ed.), A universidade medieval em Lisboa: séculos XIII-XVI. Lisbon: Tinta-da-China, 41–88.

Mattoso, José (1994). “Suporte social da universidade de Lisboa-Coimbra (1290-1527).” Penélope: fazer e desfazer a História, 13: 23-35.

Moraw, Peter (1992). “Careers of graduates.” In Hilde de Ridder-Symoens (ed.), A History of the University of Europe. Cambridge UP, vol. 1, 244–79.

Moreira de Sá, Artur (1960). O Infante D. Henrique e a Universidade. Lisbon: Comissão Executiva das Comemorações do Quinto Centenário da Morte do Infante D. Henrique.

Moreira de Sá, Artur (ed.) (1966). Chartularium Universitatis Portugalensis (1288-1537). Vol. 1: 1288-1377. 15 vols. Lisbon: Instituto de Alta Cultura.

Moreira de Sá, Artur (ed.) (1968). Chartularium Universitatis Portugalensis (1288-1537). Vol. 2: 1377-1408. 15 vols. Lisbon: Instituto de Alta Cultura.

Moreira de Sá, Artur (ed.) (1969). Chartularium Universitatis Portugalensis (1288-1537). Vol. 3: 1409-1430. 15 vols. Lisbon: Instituto de Alta Cultura.

Moreira de Sá, Artur (ed.) (1970). Chartularium Universitatis Portugalensis (1288-1537). Vol. 4: 1431-1445. 15 vols. Lisbon: Instituto de Alta Cultura.

Moreira de Sá, Artur (ed.) (1972). Chartularium Universitatis Portugalensis (1288-1537). Vol. 5: 1446-1455. 15 vols. Lisbon: Instituto de Alta Cultura.

Moreira de Sá, Artur (ed.) (1974). Chartularium Universitatis Portugalensis (1288-1537). Vol. 6: 1456-1470. 15 vols. Lisbon: Instituto de Alta Cultura.

Moulin, Léo (1991). La vie des étudiants au moyen âge. Paris: Albin Michel.

Nardi, Paolo (1992). “Relations with authority.” In Hilde de Ridder-Symoens (ed.) A History of the University of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, vol. 1, 77–107.

Norte, Armando and André de Oliveira Leitão (2018). “Violence and conflict in the Portuguese medieval university: from the late-thirteenth to the early-sixteenth century.” In Maria Cristina Pimentel and Nuno Simões Rodrigues (eds.), Violence in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds. Leuven: Peeters Publishers, 513-27.

Oliveira Marques, António Henriques de (1988). “Lisboa medieval: uma visão de conjunto.” In Novos ensaios de história medieval portuguesa. Lisbon: Editorial Presença, 80–91.

Pedro de Meneses (1504) 1964. Oração proferida no Estudo Geral de Lisboa. Lisbon: Instituto de Alta Cultura.

Pirenne, Henri (1927). Les villes du Moyen Age, essai d’histoire économique et sociale. Brussels: M. Lamertin.

Resende, André de (1534) 1956. Oração de sapiência: Oratio pro rostris. Lisbon: Instituto de Alta Cultura.

Rodrigues, Manuel Augusto (ed.) (1991). Os primeiros estatutos da Universidade de Coimbra. Coimbra: Arquivo da Universidade de Coimbra.

Schwinges, Rainer C. (1992). “Student education, student life.” In Hilde de Ridder-Symoens (ed.), A History of the University of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 1, 195–243.

Silva, Isabel Luísa Morgado de Sousa e (2002). A Ordem de Cristo (1417-1521). Porto: Fundação Eng. António de Almeida.

Sousa Costa, António Domingues de (1991). “Considerações à volta da fundação da universidade portuguesa no dia 1 de março de 1290.” In Congresso de história da Universidade de Coimbra. Actas. Coimbra: Universidade de Coimbra, vol. 1, 71–82.

Veloso, Maria Teresa Nobre (1997). “O quotidiano da academia.” In História da Universidade em Portugal: 1290-1536. Coimbra—Lisbon: Universidade de Coimbra—Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, vol. 1 (1), 129-51.

Verger, Jacques (1992). “Patterns.” In Hilde de Ridder-Symoens (ed.), A History of the University of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, vol. 1, 35-74.

Notes

1 This article forms part of the ongoing research project Œconomia Studii: Funding, Resources and Management of the Portuguese University (13th-16th centuries), funded by the Portuguese research agency (PTDC/EPHHIS/4964/2012). It is also closely related to the authors’ own individual research projects: a postdoctoral investigation related to the economic and financial aspects of Portuguese University (SFRH/BPD/115857/2016) and a PhD thesis on the Manueline Reform of Portuguese University (SFRH/BD/135867/2018).

2 Center of History of Society and Culture of the University of Coimbra (CHSC-UC); Centre for History of the University of Lisbon (CH-ULisboa), Portugal. E-Mail: [email protected]

3 Centre of History of the University of Lisbon (CH-ULisboa), Portugal. E-Mail: [email protected]

Received for publication: 19 December 2018

Accepted in revised form: 10 May 2019

Recebido para publicação: 19 de Dezembro de 2018

Aceite após revisão: 10 de Maio de 2019

Copyright

2019, ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH, Vol. 17, number 1, June 2019