|

|

Zenonian Laws on Sea Views and the Image of the City of Lisbon1

Hélder Carita2

Abstract

Following the 1755 earthquake, the royal decree that issued directives for the rebuilding of the city of Lisbon emphatically declared the abandonment of the Constitution of Zeno. This decree had its origins in Roman Law and the Code of Justinian, protecting the views from houses facing the sea and, in the case of Lisbon, views over the River Tagus.

Although historiographers of urbanism consider this law to be either extinct or forgotten, it was upheld for centuries in Portugal and had a significant bearing on the city’s architecture, helping to mold an urban culture that prized Lisbon’s visual features and landscapes. I propose to examine the way in which these laws were incorporated into, and applied within, Portuguese law. Above all, I examine how they were understood and experienced in the day-to-day life of the city, where, in the various records of petitions, agreements, contracts, and legal disputes, we can find constant references to these laws, which became a source of privilege and a zealously guarded asset, particularly among the social elite.

Keywords

Lisbon, urbanism, architecture, Zenonian laws, Roman Law

Resumo

Na sequência do terramoto de 1755 o decreto régio com as directivas para a reedificação da cidade de Lisboa afirmava de forma peremptória a abolição da Constituição Zenoniana. Esta lei que recuava na sua origem ao direito romano e ao código justiniano estabelecia a protecção às vistas das casas voltadas ao mar e, no caso de Lisboa, as vistas sobre o Tejo.

Considerada pela historiografia do urbanismo como extinta ou ignorada, esta lei manteve-se em vigor em Portugal durante séculos, tendo uma significativa influência na arquitectura como numa cultura urbanística que tendia a valorizar os aspectos visuais e paisagísticos da cidade de Lisboa. Propomo-nos analisar a forma como estas leis foram integradas e aplicadas no direito português, mas, sobretudo, examinar a maneira como foram entendidas e vividas no dia-a-dia da cidade, onde, através de petições, acordos, contractos e conflitos jurídicos, constatamos uma constante referência a estas leis que aqui vemos emergir como um privilégio e um bem guardado com zelo e orgulho, sobretudo entre as elites.

Palavras-chave

Lisboa, urbanismo, arquitectura, Leis Zenonianas, direito romano

I - Introduction

In what was apparently an unexpected occurrence, the decree of June 12, 1758, which formally rendered official the plan and strategies for rebuilding the city of Lisbon (Silva 1830: 624), explicitly and definitively abolished the Constitution of Zeno. The text of this decree established that the plan would be devised “without heed to the Constitution of Zeno and the opinions of learned figures who would seek to thwart (prohibit) buildings that might block views of the sea.”

In his work Lisboa Pombalina, José Augusto França mentions this development but interprets it as a mere legislative precaution, referring to such laws as “old Zenonian laws, which were already being ignored” (França 1977: 150). Perhaps due to the eminence of that venerable historian, the significance of these laws and their impact on the image of the city of Lisbon, together with their implications for the history of urban planning in Portugal, have never been the subject of an in-depth study.3

However, the Constitution of Zeno was not, in fact, disregarded in its time, as we find that, despite its official revocation by royal decree, it continued to exert an influence for several centuries to come through its impact on the daily lives of the people of Lisbon. Indeed, a mere two years after it was revoked, the Marquises of Abrantes drew up a notarially approved agreement with their neighbors (AN/TT, PA, Arquivo da Casa de Abrantes, P.1, Doc. 2) regarding the views from their property, the Palácio de Santos,4 while, also in 1760, the friars of the Convent of Grilos requested authorization from Lisbon City Council for an extension to their monastery, with the accompanying text stating: “which (works) will not deprive anyone of their view, as it is bordered, on one side, by the waterfront, and, on the land side, backs onto other buildings belonging to the monastery” (AML, Livro de Cordeamentos 1760 –1768, n.n.).

The lingering deference to this law in the Portuguese legal sphere is also demonstrated by a ruling from the Portuguese Supreme Court, issued during the reign of Queen Maria I and dated 1786 (Castro 1786: 578). Due to doubts about the scope of the 1758 decree, this ruling once again confirmed the revocation of the Zenonian laws relating to sea views, officially extending its application not only to the area earmarked for the rebuilding of Lisbon but also “to all districts of the capital and the other cities in the kingdom.” Once again, this underlines the significance, spread, and persistence of these laws.

Throughout the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, various licenses, council rulings, legal proceedings, and family archives bore testimony to the continuing endurance of these laws in the day-to-day life of the city. It is worth noting that, in the documentation, the Zenonian laws are normally referred to as laws relating to “views of the sea” or “views,” so that, in most cases, it is not immediately apparent that the text is actually dealing with the Zenonian laws. This opacity has made it all the more difficult to undertake any in-depth investigation of the application and impact of this obsolete legislation, forgotten over time. In my case, it took years of grappling with documents replete with references to issues relating to views before I was finally able to embark on an investigation focusing on this subject in the context of Portuguese legal history.

Protecting the views of buildings and public spaces, this law shaped an urban culture, based on aesthetic concepts of "decorum", which ultimately favor the city in adapting to the geography and preexisting landscape.

Clearly testifying to such values was the emergence of the designation of “royal views,” as mentioned in documents from that time, this term being synonymous with sweeping views of the river as opposed to those of a more lateral or truncated nature.

Whether explicitly or implicitly, the possibility of enjoying views over the River Tagus and the sea seems to have remained a kind of entitlement, even after the abolition of the regulations surrounding them. This had implications for Lisbon’s morphology and cityscape as well for the aesthetic premises underpinning Portuguese urban planning in the modern age.

II - Roman Law and Zenonian Laws on Sea Views

An examination of Zenonian laws on sea views within the context of Portuguese jurisprudence entails going back to classical antiquity and conducting a brief investigation into the origins and meaning of such legislation within Roman Law in general, and the Corpus Juris Civilis in particular.5 In their original incarnation, these laws formed part of the Constitution of the Emperor Zeno (474–491). Promulgated during this emperor’s reign, under the auspices of the Eastern Roman Empire, this constitution6 was the result of a set of rules implemented by Adamantius, the praefectus urbi of Constantinople, following the fire that had devastated much of the city during his tenure.

Their legislative contents focused on urban construction, i.e. establishing the minimum distances allowed between buildings and their permitted heights while, at the same time, the regulatory control of heights further extended to rules prohibiting the construction of new buildings that would deprive their neighbors of a sea view. Laws relating to views of the sea were only applicable to cases involving a distance of up to 100 feet between buildings and ceased to apply once this distance had been exceeded. The text authorized the construction of buildings that obstructed “a sea view if it is only from kitchens or ‘latrines’ or ‘privies’, or from stairways, passageways, connecting corridors or passages that most people call galleries.”

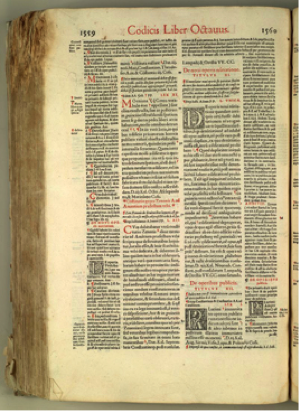

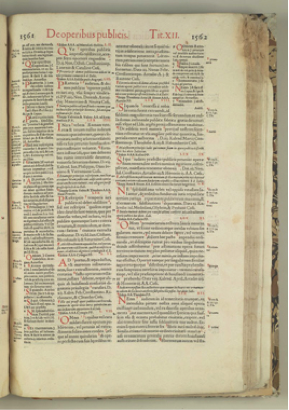

Some decades later, the Constitution of Zeno was included among the major group of laws brought together as a whole during the reign of Justinian (527–65). Given the overall name of Corpus Juris Civilis – Code of Justinian, a college of jurists led by Tribonian put together this extensive and reformative compilation, which comprised four sets of documents. An initial set of twelve books, called the Codex, represented the systematization of laws promulgated by the ancient emperors from the time of Hadrian until the reign of Justinian and was published in 534 ad. The Constitution of Zeno was included in this Codex—in Book 8, Title 10, to be precise—which deals with legislation on private buildings. This was followed by the Digestum, or Pandectas, a larger set of fifty books, which applied the laws to real life, with commentaries from leading Roman jurists. A third body of work, called Institutas, served as a kind of legal teaching manual for jurists scattered all around the Empire. Finally, the updating of legislation during the reign of Justinian led to the creation of a new body of texts that brought together the laws published after 534 ad, dubbed Novellae (the “New Constitutions” or “Novels”) or Authenticum (“Authentic Laws”). This legislative compilation included two new laws expanding upon and clarifying the Constitution of Zeno. Promulgated between 538 and 540 ad, these were known as Novel63 and Novel 165. The first sought to prevent the fraudulent calculation and use of distances between buildings and sea views, while the second clarified the scope of the concept of “sea view” (prospectus maris), which was expanded to cover all direct frontal views as well as lateral views or those from an oblique angle. These two Novelsconcentrated exclusively on sea views, further attesting to their importance under Emperor Justinian and highlighting the urban planning problems that they posed.

Fig. 1–2. Transcription of the Constitution of Zeno in the Corpus Juris Civilis, Lion, Hugues de la Porte (ed.), 1588, Book VIII, pp. 1559–62.

The Code of Justinian remained in force throughout the period of the Byzantine Empire until the fall of Constantinople in 1453, when the city was captured by an Ottoman army under the command of Sultan Mehmed II. The survival of these laws and their application in Byzantine jurisprudence is highlighted by their inclusion in the Hexabiblos, a series of laws organized by theme (rather in the manner of the Portuguese royal decrees), which was compiled in 1345 by the judge Constantinus Armenopolus. During the Ottoman period, the policy of tolerance adopted by the Turkish authorities towards the customs and laws of the vanquished citizens meant that the Greek Orthodox communities spread throughout the former empire continued to be governed by this body of legislation into which the Constitution of Zeno was incorporated.

Studies conducted by Dimitri Philippides confirmed the continuing survival on the Greek islands of architectural and urban planning traditions deriving from the Zenonian laws (Haquim 2014: 15–21), who discovered that the laws relating to sea views were being applied in various communities in the Aegean Islands. This explains the architectural tradition of urban clusters shaped by their close relationship with the landscape and the preservation of sea views.

In Western Europe, the Constitution of Zeno appears to have been of minor importance, especially if we consider that the fall of the Western Roman Empire (476 ad) preceded the promulgation of the Code of Justinian (529 ad). With the revival of Roman Law throughout the Middle Ages and a growing awareness of the Code of Justinian as a whole, the Constitution of Zeno, originally written in Greek, was eventually translated into Latin, and was thereafter known as the De aedificiis privatis.

As the study of law gained ever greater prominence at the University of Bologna, European jurists came to see the Constitution of Zeno as an isolated example of local law without any general application, with the result that it was not transcribed into the legislative framework. Legal historians such as Biondo Biondi and Valentino Capocci have expressed serious reservations as to the extent of its dissemination across Europe during the Middle Ages (Biondi 1936: 363–84, Capocci 1941: 155-84).

Portugal, however, represented an exception to the rest of Europe: the affinities between Lisbon and Constantinople were such that the Constitution of Zeno was incorporated into Portuguese jurisprudence.7 These laws acquired legal legitimacy in the modern age thanks to an important clause in the Manueline Ordinances, which was continued in the Philippine Ordinances (Silva 1991: 275). In fact, these ordinances stipulated that if the text of the ordinances lacked legal guidance on a specific matter, Roman Law should be applied in its place. The Manueline Ordinances stated that “[i]f the matter in question is not provided for by the Law, manners or customs of the kingdom, we order that it be put to trial if it is a matter that entails a sin according to the sacred canons; and if it is a matter that does not entail a sin, we order that it be judged according to the Laws of the Empire” (Manueline Ordinances,1521, Book II, Title 5).

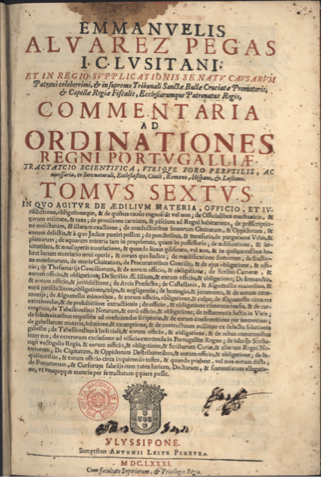

In the specific case of legal provisions about sea views, their inclusion in Portuguese jurisprudence as subsidiary law was examined by the jurist Manuel Pegas in his work Commentaria ad Ordinaçoens Regni Portugalliae, which stated, “and given that the Royal Ordinances do not grant this privilege, the view of the sea is provided for by the common law of the Romans, which the Royal Ordinances order be upheld, should provision for particular matters be lacking” (Pegas 1681, Book VI, 94).

III – From Private Law to Public Law

The first documented mention of the protection of sea views appeared during the reign of King Manuel I in a license granted to Vasco Corte Real, Jorge de Mello, and Dom Martinho Castelo Branco, the Count of Vila Nova. Dated 1521 and signed by André Pires,8 this license guaranteed a sea view (or a view of the River Tagus, in this case) to the houses of these eminent state officials, certifying that buildings could not be erected in front of them. These buildings, referred to as the “boticas dos ferreiros” (blacksmiths’ forges) formed a long, low architectural complex located beside the Ribeira das Naus. Constructed in the early sixteenth century as part of a joint enterprise between the royal house and the Lisbon City Council (Carita 1999: 53), this set of buildings served as an important support facility for shipbuilding. The importance of such workshops to the national economy was such that there was a strong possibility that they might be enlarged through the addition of extra floors, which posed a threat to the views enjoyed from the grand houses. This case proved to be something of an exception, insofar as the license was respected for over two centuries and the long, low complex maintained its Manueline form until the time of the earthquake, as we can see from pictures of this area showing the workshops stretching along the Ribeira das Naus.9

Another royal license was issued for a very similar case in the city, dating from 1517 and authorizing construction work upon a plot of land belonging to the monks of the Carmo Monastery, situated on the slopes of the Carmo Hill and enjoying sweeping views over the city’s Baixa district and the River Tagus. In order to protect the views of the houses clustered on the hill, the license specified that new buildings not on the hill should be no higher than 10 spans (2.2 meters). The text stipulated that “the houses built on the said land cannot be taller than ten spans from the ground upwards, but those on the hill can be any height desired.”10

The fact that these two licenses bore dates that were so close to one another may, in fact, be a reflection of the sweeping urban reforms that were a feature of the Manueline period in Lisbon. This was a time of intense legislative activity, stimulated by the circle of António Carneiro, the royal secretary, and André Pires, as they wrestled with issues relating to urban law and converted them into specific regulations.

Fig. 3. António de Holanda. View of Lisbon in Crónica de D. Afonso Henriques de Duarte de Galvão. Illumination on parchment. © Museu-Biblioteca Condes de Castro Guimarães, Cascais. MCCG no. 14.

One hugely significant aspect of the way in which the Zenonian laws’ provisions regarding sea views were interpreted in Portugal was the extension of their application from the private sphere to the broader domain of public law. This transition is clearly documented between 1575 and 1577 in records relating to a conflict between the Lisbon City Council and one Francisco Álvares. In fact, the dispute did not arise over the view from a house but rather from a desire to protect the views from a street, in this case a public thoroughfare—the Estrada de Xabregas. The dispute was documented in two entries in the Livros de Vereação. The first entry tells us that Francisco Álvares was called before the City Council to argue his case on July 12, 1575, with the text stating: “and as the view from the street to the sea would be obstructed, the City Council summoned the aforementioned Francisco Álvares to appear and provide a reason why such work should be necessary.” The text also makes reference to the site: “a plot of land with olive trees that runs from the walled garden belonging to Dom Diogo Deça to the edge of the wall of the garden of the estate and houses that belonged to Christovam de Brito, which is located in Calçada da Cruz da Pedra beside the Madre de Deus Monastery along the seafront, where part of the road that once ran to Enxobregas also lies.”11

Two years later, a record dated January 31, 1577 recounts how Francisco Álvares came to a mutually satisfactory agreement with the Lisbon City Council, and donated a strip of land adjacent to the Madre de Deus Monastery that overlooked the sea: “He is content not to have work carried out on that section of land that looks down to the sea, and, of his own volition, wishes the whole stretch of the waterfront to belong to the city.” In the text of the agreement, Francisco Álvares introduced a clause that obliged the City Council to agree that nothing would be built there, with the text providing the necessary clarification: “on condition that the city may at no time cause any work to be undertaken on this site other than the building of a wall, which may be no higher than five spans.”12

The perception of sea views as a public good or an urban entitlement that needed to be preserved was a question that arose periodically in the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. To this end, the Lisbon City Council petitioned the king for permission to demolish a cluster of houses built on the banks of the Tagus, “on the salty beaches of this city.” The letter, dated 1678, stated that “the houses, which are raised on walls, may be torn down, as they serve no purpose whatsoever and block the view of the sea and are detrimental to the adornment and beautification of the city” (Oliveira 1894, vol. VIII: 492).

This connection between sea views and “adornment and beautification” also appeared in another letter that underlined the aesthetic value of a sea view from Terreiro do Paço. In this instance, in 1678, the City Council requested permission from King Pedro II to demolish the curtain wall and bulwark that had been built along the waterfront of Terreiro do Paço, arguing that “it is useless for defending this city and that delightful square, while simultaneously robbing it of its sea view, and rendering the beach beyond the curtain wall a filthy place that is unfit to be the first view of the royal palace (…) which can only be avoided if His Highness grants permission for this Chamber to have the curtain wall and bulwark torn down, levelling the whole beach area, and thus restoring the view of the sea.”13

Such cases reveal that the City Council was concerned not only with the views from Lisbon’s houses but also with the squares and open spaces of the city, seeking to balance its built components and to enhance the relationships between the different elements. This concern was further bound up with the question of decorum and “adornment and beautification” that proved to be key features of the image of Lisbon.

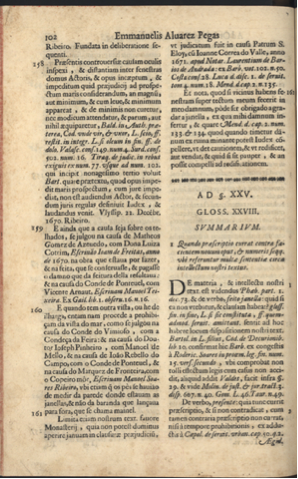

IV – “Royal Views” and the Work of Manuel Álvares Pegas

The way in which the Zenonian laws were understood and applied in Portugal was brought into sharper relief by the studies of the jurist Manuel Pegas in Comentaria ad Ordinaçoens Regni Portugalliae (Figs. 4-5).14 In this lengthy work, organized in accordance with the tradition of the medieval glossators, the writer performs a detailed analysis of each of the subjects set out in the Royal Ordinances. The subject of sea views is included under the heading of “Obligations of the Inspectors of Weights and Measures” in the chapter entitled “Buildings and Services,” which comments on different aspects of these laws accompanied by transcriptions of rulings and verdicts issued by various judges, providing clarification on how these were applied. Despite being limited to a specific elite who enjoyed the power to uphold their rights, the array of cases covered in this work provides us with a valuable overview of the disputes that took place all around the city, proving that this law was well and truly active and that the city’s residents had recourse to it with some frequency.

The sheer range of cases is particularly apparent when the question of lateral and secondary views is addressed. A ruling by the Supreme Court in 1670 refers to the existence of legal disputes between a number of eminent families, including those of the Counts of Vimioso, the Counts of Pontével, the Counts of Feira, the Marquises of Fronteira, and even the Royal Cupbearer himself. The text states: “and if he has another view, or one from the side, he cannot prevent the other one from building, as in the case of the Count of Vimioso versus the Countess of Feira, or that of Dr Joseph Pinheiro versus Manoel de Melo, or that of João Rebello do Campo versus the Count of Pontével, or that of the Marquis of Fronteira versus the Royal Cupbearer” (Pegas 1682: VI, 102).

In the commentary and the cases transcribed, it is possible to discern a partnership between the judges of the Supreme Court and the officers of the City Council, in particular the master stonemasons who were called upon not only to conduct inspections but also to propose formal solutions, indicating that they were fully aware of these regulations. As such, in the dispute between Simão da Costa Freire, Lord of Pancas, and Canon Gabriel Marques Godinho (1669), following a survey carried out by the master stonemason, the final ruling states: “It is ordered that the roof be altered and rebuilt in the fashion advised by the Master Carpenter” (Pegas 1681: VI, 93).

Fig. 4–5. Title page and page 102 of Book VI of the Comentaria ad Ordinaçoens Regni Portugalliae by Álvares Pegas, which includes his commentary on the Constitution of the Zenonian Laws on Views of the Sea.

Of even greater interest to this study is the emergence of a specific category of view, described as being a “royal view.” Due to its huge symbolic power, I believe this to be a particularly significant development in the process of interpretation that this law underwent in Portugal as well as the associated implications for urban planning and the culture of the territory. This category appears to have originated from an attempt to apply the law more rigorously, which led to the creation of a “royal view” category characterized by a sweeping, frontal panoramic view of the sea. Such royal views were distinguished from those of a lower rank—oblique, lateral or truncated—which were now excluded from such privileges, thus making the law clearer and far easier to apply.

This is evident in the dispute between Bento de Freitas and Pedro Arce, in which the judge ruled as follows: “The houses are not deprived of their view (…) most of the sea view remains from the other large windows, and nor do the houses enjoy a royal view, which is considered to be a sea view for these purposes (…) with qualities that do not apply to the appellant’s house” (Pegas 1681: VI, 98). The same term appears in the case of Pedro Gomes de Oliveira versus António Carvalho, where the judge concluded his verdict by stating: “The main view from the appellant’s house is not a royal view, but rather from a roof” (Pegas 1681: VI, 101).

The fact is that the text of the Constitution of Zeno does not contain any reference to the category of a “royal view,” nor do the two other laws included in the Novels that were promulgated during the reign of Justinian I and covered the application of this law in detail. Designating such views as “royal” undoubtedly conferred upon them a distinct note of prestige and denoted a certain appreciation of the opportunity to enjoy nature, thus contributing towards an image of the city defined by a number of crucial points and an urban morphology punctuated by scenic highlights.

V – From the Seventeenth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century

Throughout the seventeenth century and until the middle of the following century, we see that the privilege of having a sea view was an everyday concern of city-dwellers. Due to its legal scope, the work of Manuel Pegas is particularly revealing about the disputes that took place between the owners of private houses, mentioning cases in which laws had been infringed. Documentation from the Lisbon City Council and family archives also provides references to precautionary measures taken in order to safeguard individuals’ rights to sea views.

On two occasions, in 1704 and 1760, the Lancastre family—the Counts of Vila Nova and the owners of the Palácio de Santos—signed notarial agreements with their neighbors, in which the latter undertook not to assert their right to obstruct the expansion of the palace. As the Lancastre family were Grand Masters of the Order of Santiago and were ranked among the highest nobility in the kingdom, it is particularly noteworthy that even they were required to come to an agreement with their neighbors, who were of considerably lower social status. The text of the agreement stated as follows: “and Antonio Vicente and his wife acknowledge that their houses owe to the Palace of His Excellency the Count of Vila Nova the courtesy of not preventing the aforementioned palace from being raised to any height, whether in whole or in part, should the present or future Lords and owners of the said palace wish to do so, even though raising the palace would deprive the aforementioned houses of their sea view” (AN/TT, Private Archive, Casa de Abrantes, Comendadores Mores, Packet 1, Doc. 2).

Fig. 6. “Landing of King Philip II of Spain in 1619,” in João Baptista Lavanha, Viagem da Catholica Real Majestade de Filipe II. Madrid. Engraving by Ioam Schorquens, after Domingos Vieira Serrão, 1622.

While most of the aristocracy tended to respect this law, one exception was Prince Francisco, the brother of King John V, who had work done to various palaces next to the Corpo Santo Church, disregarding the fact that this would block his neighbors’ sea view. We know of this case because the Brotherhood of Our Lady of Loreto, which owned the building that had been deprived of its view, made an application to the City Council in 1753 immediately after the death of the Prince, requesting that: “With the granting of official licenses from His Majesty or the City Council, we seek to have restored what was taken from us, and to improve the property by doing so” (AML, Livro XVIII de Consultas e Decretos d'el-Rei D. João V. p. 133).

The Lisbon City Council Archives house a vast collection of documents that cover a wide range of lawsuits and legal proceedings, not only relating to architecture but also to urban planning, in which we can note the development of a discourse that included workers, council officials, building inspectors, master stonemasons, and other stakeholders from across the whole social spectrum. To take one example, when urban redevelopment work was being undertaken in Largo das Portas do Sol in 1678, the City Council made a precautionary request to the King that no property leases be granted in the area as a means of preventing “the harm that could be caused to the neighbors who have noble houses in this area, if they are deprived of their sea view” (AML, Livro V dos Assentos do Senado Oriental, p. 8).This case is particularly significant if we bear in mind that this square is now considered to be one of Lisbon’s most iconic open spaces and is regularly featured in all manner of tourist material.

Another interesting case is the application submitted to the City Council by the Brothers of the Holy Sacrament in the parish of São Miguel de Alfama in 1753 for the construction of two residential buildings. The text stated that the appellants acknowledged that “this cannot have anything more than a small second floor, as it would otherwise rob the neighboring properties of their sea view” (AML, Livº II de Reg e Cons. e Decr. do Sr Rei D. José I, p. 61v).

Fig. 7. Anonymous – Lisbon viewed from the Palace of the Marquis of Abrantes. First half of the eighteenth century. ã Collection of the Museum of Lisbon | CML | EGEAC, MC.PIN.264.

The plans for a new quay running all the way from the Ribeira das Naus to Belém, which were developed during the reign of King John V, belong to the category of strategic urban planning. Had this project come to fruition, it would have had an impact comparable to that of the aqueduct as it would have required an accumulation of sediment along the riverside all the way from Terreiro do Paço to Belém. The project envisaged the construction of houses along the riverfront between Terreiro do Paço and Alcântara. These would create a line of urban façades punctuated by canals and streets running perpendicular to the riverfront along the banks of its tributaries. According to the brief created as part of the process, the project had two drawbacks, as mentioned in the text: “There are only two possible obstacles of note: firstly, that many of the houses there will lose their view of the sea.” I was unable to ascertain the official reasons for the discontinuation of this project, despite its having the backing of the Secretary of State, António Guedes Pereira. It seems to me that the project’s brief was clearly aware of the fact that the urban plans would cause the view’s obstruction of a large number of houses and palaces situated along the waterfront, whose owners occupied important positions within the royal administration.

VI – Conclusion: From Order to the “Adornment and Beautification of the City”

The incorporation of the “Zenonian laws on sea views” into Portuguese jurisprudence allows us to detect unusual parallels between Constantinople and Lisbon, two large metropolises which, despite being located at the opposite extremes of Europe, both owed their origins and subsequent development to their close relationship with the sea and shipping routes. In both places, the Zenonian laws on sea views became part of a cultural backdrop in which the sea played a key role in the city’s history and self-mythification, while the way in which these laws were adopted and applied in Portugal impacted on the country’s architectural culture and laid the foundations for urban planning in the modern age.

The importance of the Tagus and of views of this river as a defining element of Lisbon’s image, as reflected in the iconography of the city from the early sixteenth century onwards, was constantly highlighted over the centuries in the form of illuminations (Fig. 3), engravings (Fig. 6), and paintings (Figs. 7–8), with abundant depictions of the city as seen from the river, making this an iconic image of Lisbon.

Fig. 8. Anonymous. Panoramic View of Lisbon and Departure of St. Francis Xavier to India, c. 1730. ã Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga. Lisbon.

As outlined above with specific examples, this culture of prizing sea views is most aptly demonstrated in the references to the category of “royal views,” which, notably, did not appear in the original legislative text from the fifth century ad. By drawing a distinction between sweeping views over the Tagus and the sea, as opposed to lateral or oblique views, this designation introduced a certain hierarchy and a clearly symbolic dimension into the way in which people approached the idea of enjoying views of the city. In this sense, I contend that urban morphologies and design are defined not only as a function of the way in which buildings and spaces enjoy views of the landscape but also the extent to which they can be enjoyed from the outside, thus lending an expressly scenographic dimension to the image of the city.

At the same time, moving beyond the original content and scope of these legal documents, in Portugal, the Zenonian laws took on the status of public law and constituted a common good when applied to urban spaces such as streets and squares—a phenomenon that was not envisaged in the original text and brought its own particular undertones to the quintessentially Portuguese urban culture. The fact that sea views were prized in this way established a connection between the landscape and the constraints caused by the terrain, so that enhancing the attributes of the site ultimately made a crucial contribution to an urban planning approach that made the city’s image a central consideration.

By making allowances for the place itself and respecting the rights of others, this law was fundamental for a type of urbanism shaped by values of decorum, as Rodrigo Almeida Basto argues in relation to the villages of Minas Gerais and the traditionally Portuguese approach to town planning, which he sees as “based on attention to customs, the conditions of the place itself, and the pre-existing structures” (Bastos 2014: 227). In the same way, one could sum up by saying that the Zenonian laws appear to have made a defining contribution towards a fundamental characteristic of Portuguese urban planning, identified by Alexandre Alves Costa as the intelligence of a place, which he defines as “a unique compatibility between organicity and rationality in one’s understanding of the landscape and urban functionality” (Costa 2007: 13).

Abbreviations

AN/TT – Arquivo Nacional Torre do Tombo (Torre do Tombo National Archives)

AML – Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa (Lisbon Municipal Archives)

PA – Private Archive.

Cod. – Codex

Livº. – Livro (Book)

P. – Packet

Doc. – Document

Primary sources

Castro, Francisco Rafael (1786-1799). Collecção Chronologica dos Assentos das Casas da Suplicação e do Civil, Coimbra, Universidade de Coimbra, Vol. II.

Oliveira, Freire, Elementos para a História do Município da Cidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Typografia Universal, Vol. VIII.

Ordenações Manuelinas,1521, Book II, Tit. 5

Pegas, Emmanuelis Alvarez, (1680-1703). Comentaria ad Ordinaçoens Regni Portugalliae , 16 vols, Lisbon, Ulyssipone Michaelis Rodrigues.

Silva, António Delgado (1830). Constituição da Legislação Portuguesa desde a última compilação…, Lisbon, Tipografia Maiguense, vol. III.

References

Bastos, Rodrigo, (2014). A Arte do Urbanismo Conveniente: O Decoro na Implantação de Novas Povoações em Minas Gerais na Primeira Metade do século XVIII, Florianópolis: Editora da UFSC.

Biondi, Biondo (1936-37). “La L. 12 Cod. de aed. priv. 8, 10 e la questione delle relazioni legislative tra le due parti dell'impero.”Bullettino dell'Instituto di Diritto Romano Vittorio Scialoja, XLIV, pp. 363-84.

Capocci, Valentino (1941). “Nota perle storia del testo della costituzione dell’imp. Zenone” in Studia et Documenta histórica Iuris, Rome, Nº 7, pp. 155-84.

Carita, Helder(1995). Le Palais de Santos, Lisbon:Ed. Michel Chandaigne.

Carita (1999). Lisboa Manuelina e a Formação de Modelos Urbanísticos da Época Moderna, Lisbon: Livros Horizonte.

Costa, Alexandre Alves (2007). “Portugal, Cidade e Arquitectura” in Revista de História da Arte, UNL, nº 4.

França, José Augusto (1977). Lisboa Pombalina e o Iluminismo, Lisbon: Livraria Bertrand, p. 150.

Hakim, S. Besim (2014). Mediterranean Urbanism-Historic Urban/Building Rules and Processes, New York, Springer.

Monteiro, Cláudio (2013). O Domínio da Cidade, Lisbon: Ed. AAFDL, pp. 104-5.

Nogueira, Adriana Freire (2010). “Não Tirem a Luz nem a Vista. O Respeito pelo Espaço dos Outros” in Espaços e Paisagens. Antiguidade Clássica e Heranças Contemporâneas. Vol. 3, História, Arqueologia e Arte.Coimbra, APEC.

Osuna, Belén Malavé, (2000) Legislación Urbanística en la Roma Imperial a propósito de una Constitución de Zenón, Malaga: Universidade de Málaga.

Silva, Nuno J. Espinosa Gomes da, (1991). História do Direito Português: fontes do direito, Lisbon: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, p. 275.

Notes

1 Text written under the scope of the research project “Arquitectura regimentada em Portugal, século XVI-XVII: processos de regulamentação desenvolvidos pela Provedoria de Obras reais no seu tempo longo.” (FCT/DFRH/SFRH/BDP/86848/2012). Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, European Social Fund, and the Portuguese Ministry of Education and Science.

2 Institute of Art History-FCSH/Nova University of Lisbon, Portugal. E-Mail: [email protected]

3 As far as the legal aspects are concerned, it would be remiss not to mention the recent study by Cláudio Monteiro, O Domínio da Cidade, a PhD thesis presented at the Faculty of Law of Lisbon University, 2010, which includes a chapter devoted to the Constitution of Zeno.

4 Now the residence of the French ambassador in Portugal, this building served as the royal palace between the reigns of King Manuel and King Sebastião before passing into the possession of the Lancastre family, the Masters of the Order of Santiago, and, subsequently, the Marquises of Abrantes (Carita 1995).

5 At the European level, the most comprehensive and in-depth study of this subject was conducted by Belén Malavé Osuna (2000). In Portugal, it is also worth highlighting the work of Adriana Freire Nogueira (2010). Both of these studies examine such legislation within the context of Roman Law.

6 As they were written in Greek, the official language of the Eastern Roman Empire, these laws are also known as Zeno’s Greek laws.

7 The transposition of the Constitution of Zeno into Portuguese law is touched upon, albeit briefly, in Monteiro (2013).

8 AN/TT, Místicos, Book 6, p. 145.

9 Among the various pictures of the area around the Ribeira das Naus, the panorama of Lisbon depicting the departure of St. Francis Xavier for India, and dating from the early eighteenth century, gives us the most detailed impression of how this would have looked. Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga.

10 AN/TT, Cartório do Convento do Carmo, packet 20, p. 1, Sequeira 1939: Vol. I, 254-5.

11 AML – Chancelaria da Cidade, Livro III de Vereação, p. 6.

12 AML – Chancelaria da Cidade, Livro III de Vereação, p. 1616v.

13 ACML, Livro IV de Regimentos de Consultas e Decretos do Sr. Rei D. Pedro II, p. 215 v.

14 Comprised of 16 books, this work, published between 1680 and 1703, provides a commentary on the Royal Ordinances and details the various verdicts and rulings issued by the foremost jurists of the time for each of the themes covered therein (Pegas 1680–1703).

Received for publication: 13 February 2019

Accepted in revised form: 9 May 2019

Recebido para publicação: 13 de Fevereiro de 2019

Aceite após revisão: 9 de Maio de 2019

Copyright

2019, ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH, Vol. 17, number 1, June 2019