|

|

Evading the War: Deserters and Draft Evaders from the Portuguese Army during the Colonial War1

Miguel Cardina2

Susana Martins3

Abstract

This article analyzes the question of deserters and draft evaders from the Portuguese army during the colonial war. Utilizing as its starting point the recent discussions taking place about this issue in Portuguese society, the analysis seeks to expand the historiographical knowledge that has been built up about this theme, contributing fresh information and new interpretations relating to the matter of disobedience to military conscription. With this aim in mind, we set out to reevaluate the stance that Portugal’s opposition groups adopted in relation to the question of desertion, both at the domestic level and in exile, examining the various typologies relating to the “refusal” of the war and collecting new data on the topic. Important steps will thus be taken towards a quantification of this phenomenon, including the provision of analytical observations that help to put it into perspective.

Keywords

Colonial war; desertion; Estado Novo; anticolonialism

Resumo

O presente artigo toma como objeto de análise o lugar dos desertores e refratários da tropa portuguesa durante a guerra colonial. Partindo da forma como o tema tem vindo a ser debatido recentemente na sociedade portuguesa, procura-se avançar no conhecimento historiográfico sobre o tema, trazendo novas informações e interpretações sobre a desobediência à incorporação militar. Nesta medida, revisita-se a posição dos diversos sectores oposicionistas portugueses perante a deserção, no interior e no exílio, examinam-se as diferentes tipologias associadas à recusa da guerra e compilam-se dados novos sobre o tema, nomeadamente para a quantificação do fenómeno, complementados com notas analíticas que contribuem para a sua contextualização.

Palavras-chave

Guerra colonial; deserção; Estado Novo; anticolonialismo

The question of disobedience in the context of Portugal’s colonial war remains a little known and relatively undiscussed topic. Regarding the subject of desertion in particular, Irene Pimentel called it a “controversial, almost taboo theme in Portugal” (Pimentel 2014b), while Rui Bebiano speaks of its elusive and marginal status in the country’s collective memory (Bebiano 2016).

Nonetheless, there has been a renewed interest in recent years, with references to the theme of desertion to be found in a variety of books, articles, reports, and plays written about the opposition to war and about exile.4 Admittedly, in recent times, this inhibition has been challenged by the creation of associative structures dedicated to recovering the memory of desertion and by the promotion of events aimed at discussing its historical relevance.5 But the public echoes of such events have also revealed a sense of unease—widely displayed in comment boxes, blogs, and social media such as Facebook—on the part of social sectors that still see the gestures of disaffection about the war as a morally unacceptable stance and consider the discussion and scrutiny of the theme as irrelevant.

The sociopolitical context that has emerged in post-dictatorial Portugal should be taken into account when analyzing the subject of the refusal to take part in the war. First of all, the active participation of members of the military in the process of political change set in motion in Portugal by the events of April 25, 1974—and in the dynamics of the ensuing revolutionary period—led to the development of a rigid view about this question, due to the distinction that was made between a dictatorship bent on waging a war in order to maintain possession and control of the colonies and the military men who fought the war on the ground. Notwithstanding the role played by the military in overthrowing the dictatorship and creating the conditions for bringing the war to an end, the years that followed failed to generate the appropriate climate for addressing two critical dimensions of that event: the violence of war and of its modes of expression, still known about today, but in a somewhat fragmentary fashion, and viewed not so much within the framework of colonial domination as from the viewpoint of the logic of military action-reaction; and the importance of disobedience to the military structure as a gesture that needs to be questioned as both a cause and effect of the weakening of the war’s social legitimacy. On the other hand, the notion of a “patriotic duty” to be honored by young men, even in circumstances of extreme physical and psychological danger, remained a determining factor. Cultural motives linked to honor, pride and masculinity all pointed in the same direction, and they still have currency today when it comes to assessing the various gestures of dissent in relation to the war.

In this article, we focus on those types of refusal of the war that involved failing to report for military service or removing oneself from the military altogether. Our analysis centers on the deserters and the draft evaders from the Portuguese army. Some new data is presented on the subject, resulting from recent archival research, and complemented with analytical observations for a better historical contextualization.

The Opposition to the Dictatorship and the Theme of Desertion

As the main organized force of anti-fascist opposition to the regime, the PCP (Portuguese Communist Party) developed an anti-war discourse as early as 1961 with Avante!, the party’s official newspaper, inciting soldiers to refuse to embark on the ships taking the troops to war and to reject the role of oppressors of the Angolan people.6 In 1965 and 1966, appeals to collective desertion were common, accompanied by a discourse that emphasized the impact of war as highly costly in terms of human lives and national resources.7 But it was not until July 1967 that a Central Committee resolution clarified the party’s official position: Communist militants “must not desert, unless they have to join a collective desertion or are in imminent danger of being arrested as a result of their revolutionary activities.” In short, the party advised its members against deserting individually (see also Cardina 2011: 251-279; Madeira 2013 and Cordeiro 2017)8.

During the 1960s, dissent against the war within Portugal remained mostly circumscribed to a few circles of reflection and activism. This anticolonial activism began to make itself felt especially among the more politicized members of the student youth, whether because it was more permeable to such structures as the “Casa de Estudantes do Império” [House of the Students of the Empire] (Castelo and Jerónimo 2017), or because of the haunting specter of conscription. This opposition to the war was made clear in February 1968, with the rally against the Vietnam War held in front of the US Embassy in Lisbon, largely organized by sectors of the emerging far left. On the other hand, the list of demands of the student movement that swept across Coimbra in 1969 still made no explicit mention of the colonial war (Bebiano 2003; Cardina 2010).

The political far left, and the Maoist camp in particular, openly advocated desertion as a legitimate political gesture (Cardina 2011).9 Groups like O Comunista / O Grito do Povo [“The Communist / The People’s Outcry”] (which in 1973 merged to form the Portuguese Marxist-Leninist Communist Organization) called for armed desertion at the end of the training period. In this way, refusal of the colonial war could be combined with a knowledge of the use of weapons and related material, deemed essential for starting the revolution.10 Viewing desertion as a “lesser evil,” the PCP(m-l) (Communist Party of Portugal, Marxist-Leninist) believed that the correct move consisted in carrying out “anticolonialist agitprop work among the soldiers who were about to leave for the war.”11 Created in September 1970, the Movement for the Reorganization of the Party of the Proletariat (MRPP) called for the establishment of “centers of anti-colonial resistance aimed at organizing anti-conscription strikes, the sabotage of equipment, collective disobedience and desertion, and permanent anti-war agitation.”12

The recognition of the right of all peoples to self-determination and independence, the denunciation of the war, and the affirmation of the close link between the anti-fascist and anti-colonialist struggles had actually been championed by the National Liberation Patriotic Front (FPLN), a unitary movement that since its inception in late 1962 had brought together communists, socialists of different shades, and delgadistas, old supporters of Humberto Delgado (Martins 2018). The establishment of a FPLN secretariat in newly-independent Algeria was a clear indication that some of the political sectors represented in this organization saw the colonial question as a priority and sought a rapprochement with the nationalist movements of the Portuguese colonies. The young country saw the establishment of an important anti-colonialist, revolutionary platform that included official delegations from the various nationalist movements of the Portuguese colonies (see also Simon 2011).

Desertion as an “objective form of active cooperation with the Africans” was first mentioned in the context of solidarity with the anti-colonial struggle.13 Albeit without offering an elaborate theory on the subject, the FPLN press—not only Voz da Liberdade [Voice of Liberty] radio, but also the periodicals and other propaganda printed by it—made insistent calls for resistance against the war. As Passa Palavra [Word of Mouth], the official mouthpiece of the FPLN troops, explained, this included “refusal to participate in military operations, disobedience of criminal orders, and, in certain cases, rebellion.”14 In fact, defectors from the Portuguese Armed Forces had been arriving in the Algerian capital since 1963, some of them handed over to the FPLN by the PAIGC (African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde) after expressing interest in cooperating with the opposition’s struggle.15 The handing over of prisoners, amidst much publicity, became relatively frequent in the years that followed, with a major role being played by the various liberation movements and with the Algerian Red Crescent serving as mediator.

Equally significant was the activism of some small groups of Catholics, who disseminated alternative information about the war. The first issue of Direito à Informação [“Right to Information”], a clandestine newspaper that openly claimed to be against the regime and the colonial war, came out in 1963 (Almeida 2008). In the 18 issues published until its demise in 1969, the war was one of the newspaper’s most discussed topics, with growing prominence being given to the denunciation of the economic and political interests working behind the scenes, colonial violence against the native peoples, and the misinformation provided by the Portuguese authorities. An even greater coverage could be found in the editorial projects Sete Cadernos sobre a Guerra Colonial—Colonialismo e Lutas de Libertação [Seven Booklets on the Colonial War—Colonialism and Liberation Struggles] (issued in 1971) and BAC—Boletim Anti-Colonial [BAC—Anti-Colonial Bulletin] (from 1972 onwards). The same group of activists was behind the organization, in Lisbon, of two vigils for peace that had a powerful impact on national public opinion: one in the church of São Domingos in 1969, the other in the Rato Chapel in 1973.

The anti-war propaganda, with its impact on the troops’ morale and on the population at large, made the military authorities uneasy. According to an army document, the growing visibility of the war in the repertoire of student protests after 1969/70, the presence of the theme in the 1969 election campaign, and the activities organized at the end of that year in connection with World Peace Day were unequivocal signs of the “deterioration of the population’s state of mind in metropolitan Portugal.” The mood was “especially noticeable in student and progressive circles,” and had been forged “for political ends by a variety of partisan factions.”16 Months later, Sá Viana Rebelo, the Minister of National Defense and the army, went so far as to accuse the universities of being “veritable centers of subversion.” He regarded the attendance of higher education courses as being the cause of the desertion to Sweden of six non-career lieutenants who had “received the inspiration required to betray the motherland and launch a vile campaign abroad against their country and their comrades in the Army, which they had never truly served” (Cardeira 2016: 109-110).

The conditions for the induction of this radicalized influx was another source of concern for the military authorities. Normally, recruits labeled as “activists” by the political police would be directed to the Disciplinary Company in Penamacor, where they would be kept under better control and thus be prevented from politicizing other military units. But the significant rise in the number of young men thus labeled forced a reassessment of that option. In 1970, the Army Minister himself warned the political police about the possible repercussions of sending to Penamacor “31 individuals with a university background, including two medical doctors, one engineer and 12 medical students.”17 The Director-General for Security heeded the warning, admitting that it would “be more prudent and advisable to alter the contents of the information already provided,” and changing the categorization from “activists” to “suspicious characters.” That would make normal induction possible, although the young men would remain subject to “special [surveillance] measures.”18

In the area of culture, a major role was played by what were known as “protest songs”19 and by such cultural structures as the Teatro Operário [Workers’ Theater], a collective of emigrants living in France who used the theater to convey powerful political messages. One of their plays—O Soldado [The Soldier], which first opened in 1972—portrayed with great accuracy the life of a soldier who, after being captured in Angola by the liberation movements, had been sent to France, where he had received assistance from the Deserters’ Committees. There he met a former comrade from training camp who had “deserted with weapons,” and both finally agreed that the war was iniquitous and that it was important to fight it head-on (Costa 1980).

The theme of desertion thus became a kind of litmus test for the opposition groups. Contrary to what happened in the case of other conflicts in other latitudes, it had no connection—at least not explicitly—with organized demonstrations in favor of pacifism, but was rather imbued with anticolonial rhetoric or language condemning colonial war as unjust. The political debates on desertion and some of the practices to which they gave rise (such as having spurred a number of desertions or the establishment of Deserter Committees) should not, however, be confused with desertion per se. In fact, the concrete phenomenon of desertion entailed personal choices and personal trajectories that were considerably more pluralistic and multifaceted, marked by specific circumstances that made (or failed to make) those actions possible, and driven by motives that frequently could not be subsumed into what might hastily be perceived as an ideologized gesture.20

The Deserter—Categories and Quantifications

The legal-military definition differentiated between deserters, draft evaders, “compelled” and defaulters, each category involving a specific penal framework. In its explanation of the categorization system in peacetime, the Law on Conscription and Military Service identified as a defaulter the person who failed to appear for the military medical inspection, as a draft evader the young man who had been passed fit but who failed to report to the conscription district or the unit to which he had been assigned, and as “compelled” the individual under the age of 45 who failed to present himself for reclassification (or re-inspection).21 In turn, the Code of Military Justice defined as a deserter the serviceman who, having abandoned his post, remained unlawfully absent for more than eight consecutive days.22 In the event of war, the deserter status was significantly extended in order to encompass all the above-mentioned categories—defaulter, draft evader, and compelled—with the tolerance period for unlawful absence while on military duty being reduced to three days.23

Non-compliance with any of the forms described above led to action being taken to capture the offenders, either by the military authorities or by the police forces.24 It was then up to the Military Courts to punish deserters, regardless of whether they had voluntarily surrendered or been captured. As was the case with categorization, punishment by the courts differed in times of peace and in times of war, not to mention the fact that sentences were correlated with the offender’s respective rank, with officers receiving the heaviest punishments.25 It is interesting to note that, although Portugal sustained a substantial war effort between the years 1961 and 1974, compliance with these legal instruments followed peacetime provisions with respect to the period of time after which a serviceman was considered a “deserter.”

Up to now, the data available on desertion was very disparate and do not allowed for the formation of a comprehensive picture of this phenomenon. As early as 1977, África. A Vitória Traída [Africa. The Betrayed Victory], written by Generals Luz Cunha, Kaúlza de Arriaga, Bethencourt Rodrigues, and Silvino Silvério Marques, put the number of cases until 1973 at 181. These figures refer to desertions occurring in the colonies and have been extrapolated from a total of 103 desertions reported for the 1961-1969 period. Although this was the official total, it was impossible to arrive at an “exact number” (1977: 78-87). The same figure was given in 1994 by João Paulo Guerra, who mentioned 101 desertions in Angola, 59 in Guinea and 21 in Mozambique (1994: 387). These figures diverge from those mentioned in Resenha Histórico-Militar das Campanhas de África (1961-1974) [Historical-Military Review of the African Campaigns (1961-1974)], a publication of the Army Staff, which put the number of deserters at 227 in 1969 alone, although this figure actually included both continental Portugal and the colonies (1988: I, 247).

Both this figure, pertaining to just one year of the war, and the lower figures mentioned by the authors of A Vitória Traída corroborated the notion that this was a “rather exceptional practice” that never really became “a serious concern” for the military leadership, and which ultimately could be regarded as indirect proof that the Portuguese government enjoyed popular consent with regard to the continuation of the war in Africa (1977: 78-87). However, such a reading seems to be belied by the classified documents circulating among the military and police leadership, on which this present analysis is based. The documentation in question makes constant references not only to the figures for desertion and unlawful absenteeism, but also to the frequent efforts to determine the circumstances under which these situations occurred—especially in the event of concerted action or if career personnel were involved—and to monitor very closely the opposition’s pronouncements and activities in relation to this question.26 In addition, a Deserters’ Section was created in 1964 within the Military Police, entrusted with the specific mission of dealing with deserters and draft evaders. The military authorities stressed the effectiveness of this section, as after only 17 months of activity it was already holding a total of 170 deserters and 60 draft evaders in detention.27

Although fragmentary, the collected data indicate that from February 1961 to December 1973 there were 8,639 desertions in the regular army.28 This figure is, however, incomplete, as it fails to consider the navy29 and air force data in an exhaustive manner and does not cover the entire war period in all the territories.30 On the other hand, it basically refers to successful desertions only, which ultimately amounted to actual losses for the Portuguese Armed Forces. In other words, the figure leaves out the failed attempts, i.e. the undoubtedly greater number of deserters who voluntarily surrendered to the military authorities or were soon captured.31 In fact, according to Supintrep data, from 1970 to 1973, the number of actual desertions accounted for between 42 and 51 percent of all unlawful absences recorded. Furthermore, the numbers are dependent on the information provided and gathered by the military authorities.32

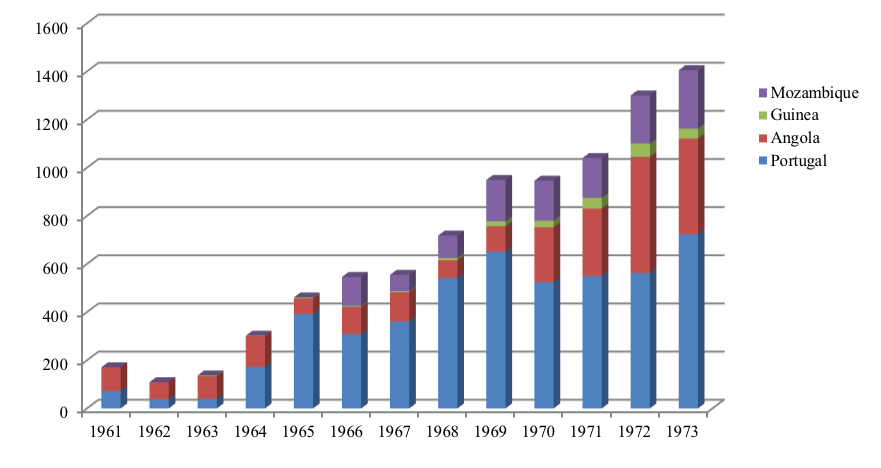

Such gaps notwithstanding, the compiled data suggest an overall steady increase in desertions over the 13 years of the war (see Chart 1). While, in the first three years, the number of instances remained below 100, in 1964, they rose to 300. The phenomenon continued to rise in the years 1966-1967, with the number of cases reaching almost 550. The next two years saw another significant increase, with 718 cases in 1968, and 949 in 1969. In 1970, the total number of occurrences remained at about the same level as in 1969, but there was a fresh rise in 1971, with more than 1,000 cases (1,040, to be precise). In 1972, desertions totaled 1,300, and in 1973, they reached 1,405 cases.

The total thus established comprises very significant differences, depending on the location under analysis: more than half of the desertions occurred in mainland Portugal and the islands of the Azores and Madeira (4,941 cases), whereas there were 2,257 occurrences in Angola, 1,227 in Mozambique, and 214 in Guinea. With regard to the cases recorded in the African territories, it should also be pointed out that the vast majority involved local contingents of the regular army. This is suggested by data for the years 1971 and 1972 from the Command-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Angola, which placed the number of deserters from the Provincial Conscription at 293 and 428 respectively, while those from the Mainland Conscription serving in the territory did not exceed ninety-eight in 1971 and eighty-five in the following year.33 A similar scenario was to be found in Mozambique, where 106 desertions were reported for local conscription in 1971 as against twelve for Mainland Conscription, and this disproportion continued into the following year, with two hundred cases among the local troops and thirty-four among the “continental” servicemen.34

Finally, it is important to note that the overwhelming majority of deserters were privates and recruits, although, in metropolitan Portugal there was a significant increase, from 1968 onwards, of cases involving officers. The total number of occurrences rose from four to sixteen during that year and remained at about the same level in 1969. There was a new, more significant leap between 1969 and 1970, with that figure rising to thirty, and thereafter remaining stable until 1973.

Disobedience as a Problem

Although each desertion followed its own unique path, they can still be grouped together into three main types. In the first group, deserters and draft evaders were based in metropolitan Portugal and for their most part headed for (“dão o salto,” “leaped to,” as the expression then went) other parts of Europe, to live there as emigrants. The second, more restricted, group was comprised of Portuguese young men who had deserted from Africa in exceptional situations and under very hostile circumstances. They either surrendered voluntarily to the nationalist movements or fled to the countries bordering the Portuguese colonies where they happened to be stationed. In this case, they would usually be steered towards Algeria, where they then joined the Portuguese community of exiles or awaited transfer to a European destination. The third group was made up of the deserters from local recruitment who formed part of the Portuguese armed forces. They followed a variety of routes, with some returning (sometimes temporarily) to their communities of origin, others fleeing to neighboring countries, and yet others joining the ranks of the liberation movements.

Thus, the circumstances of desertion could vary a lot. On metropolitan soil, it tended to occur either during the military leave granted immediately prior to embarkation to one of the various “theaters of operations,” involving young soldiers with no war experience in the colonies, or else when returning home for a leave of absence during a tour of duty. A common expedient used to effect the desertion consisted in requesting permission to leave the country temporarily.35 Besides immediately arousing suspicion on the part of the authorities, this path was not always a viable option, and so the majority of deserters chose to be smuggled out of the country. But this also involved obvious problems, beginning with how difficult it was to have the political connections or the necessary amount of money to make contact with the networks of smugglers—the passadores.

Things became even more difficult for those fighting in the colonial spaces, where the surveillance was tightest, local contacts virtually nonexistent, and the terrain particularly adverse. The risk of being shot dead by the enemy (or even by the Portuguese troops) further aggravated the extreme uncertainty that potential deserters already felt about the reaction of the neighboring countries, where they could well be faced with incarceration and a charge of clandestine immigration or, worse still, the prospect of being returned to the Portuguese authorities.36

As the colonial war extended over time, the Portuguese forces underwent a process of “Africanization” (Gomes 2013). At the same time, increasingly urgent warnings were being sent to the military commands, stressing the need to exercise stricter control over the local contingents, accompanied by systematic counter-propaganda programs. One of the recommendations consisted in identifying listeners to radio stations broadcasting from “countries hostile to us” and monitoring their connections and activities,37 since it was imperative “to avoid desertions, whose frequency has increased, and which most of the time result in information of interest being leaked to the En. [Enemy].”38

On the other hand, the act of deserting could take place in very diverse contexts. While, in some cases, a deserter might flee the barracks, at other times, soldiers escaped from prison or a military hospital, for example. In the latter case, it would often happen that wounded soldiers, forced into long periods of internment and painful treatment without adequate psychological support and deprived of any family or social interaction, would extend their leaves or even absent themselves without authorization from the facilities to which they had been committed, thus ending up being considered deserters.39 The fact was that there were different factors in play, deriving from the multifaceted and “infrapolitical” (Scott 2013) clashes with discipline, hierarchy, and military duty, from the pressure caused by war as an extreme experience, from the marks inflicted by vivid episodes of violence, and/or from an anti-war, if not anti-colonialist, stance.

It should also be noted that the growing “deterioration of military discipline and morale” was sensed by the military authorities and was considered a cause for concern, particularly when it affected the higher ranks. As early as May 1968, in addition to discussing the desertions per se, a confidential note from the Army Chief of Staff highlighted the requests that had been made to be sent to the reserve, the psychoses and nervous diseases that were to be found among commissioned and non-commissioned officers alike, the apathy of some battalion commanders, and the displays of political dissatisfaction on the part of the career officers. The proposed response focused on “intense psychological warfare,” namely by increasing the amount of time spent in “the metropolis” between tours of duty, offering better transportation for the families who moved to the colonies where the war was being waged, and equalizing salaries in the three “theaters of operations.”40

It is important to bear in mind that the definition of the category “deserter” was instituted by the state-military power and that it did not cover the whole question of disobedience in the context of a war. In order to address this question properly, we must also take into account the number of defaulters (i.e. the young men who failed to present themselves for military inspection) and draft evaders (i.e. those who did submit to the inspection but failed to present themselves at the time of conscription). Thus, leaving the country before being conscripted meant dodging training camp, for otherwise desertion would have to be postponed and carried out under greater surveillance. In fact, many of the young men in metropolitan Portugal who had already made the decision in their own minds not to fight in Africa seem to have taken one of these options.

This is further suggested by the total numbers of draft evaders in the years 1967-1969, mentioned in an internal document studying the return to the country of young men who had not fulfilled their obligations with regard to military service (see Table 1). As to the defaulters, (i.e. the young men who failed to present themselves for medical inspection), their number in the “metropolis” rose steadily from 11.6% in 1961, when the war first broke out, to over 20 percent by 1970 (see Table 2).41 These figures allow us to infer that about 200,000 out of one million young men registered for military service failed to report for military inspection.

It should be pointed out that the high number of defaulters is mostly related with the Portuguese social formation itself, the dynamics of migration, and the country’s historical difficulties in terms of exercising social control. As a matter of fact, military records tell us that the share of defaulters was 16.6% in 1933, compared with 12.7% in 1940 and 9.8% in 1950, and that these figures rose as a result of the war (Resenha, 1998: 268). Such data differ substantially from those cited by the above-mentioned authors of Africa. A Vitória Traída, who mentioned 40% of defaulters in the years 1958-1960 and 29% in the period 1961-1973 (Cunha et al., 1977: 79-80). With their omission of any sources, the latter claims were part of an effort to legitimize the war in the period immediately after the revolution of April 25, 1974. Based on those figures, the authors stated that:

“It should be a source of pride to know that as far as defaulters, “compelled” and draft evaders were concerned (and surely also with regard to deserters from Mainland Portugal, for these situations were statistically tracked), the percentages of the drafted contingent improved during the war years compared to the previous period (…) [indicating] a behavior that was probably unparalleled in the world” (Cunha et al., 1977: 83).

The reality was different. It seems beyond dispute that the high number of defaulters is linked to the strong migratory flow that the country was experiencing at that time. These very findings were highlighted in a 1968 study carried out by the army staff. The study detected a broad correspondence between the number of absentees and the fluctuations in emigration by region, with higher percentages in the country’s northeastern region and the islands of the Azores and Madeira.42 The perception of that correlation was surely the reason why an amnesty for the crime of illegal emigration was granted towards the end of that year,43 followed soon afterwards (in February 1969) by an amnesty for the defaulters, “compelled” and draft evaders who presented themselves of their own free will to perform military service.44 However, these measures were insufficient to solve the problem. When the situation was reassessed in the first months of 1971, it was admitted that “the number of defaulters has reached worrying proportions, making it impossible in the short term to foresee its decrease or the return of substantial numbers of migrants with an irregular military status.”45

While there is no clear direct link between the increase in the number of defaulters and the anti-colonial sentiment, it is also true that the rigid distinction between evading the war and emigrating—or, to put it differently, between “political” and “economic” emigration—renders this whole issue harder to understand. Rather than seeing these men as victims, it is possible, as Victor Pereira points out, to interpret the Portuguese emigration of the 1960s and 1970s as part of the resistance strategies developed by the popular classes as subjects seeking to expand their social space (Pereira 2007). In fact, the very gesture of emigrating touched upon a variety of issues, with material sustenance and the search for new opportunities abroad often intersecting with the need to escape other types of constraint. Among those constraints, especially with regard to the lives of young men, was the grim specter of being mobilized to fight in a war thousands of miles away from home, in a situation of great physical and psychological danger.

Concluding Remarks

The figures on the theme of desertion adduced above result from a comparison and cross-analysis of different accessible archival sources. Taken together, they suggest that, although frequently neglected, the refusal to take part in the war was a significant factor during the period of the colonial conflict, and that it should be interpreted within the context of the difficulties felt by the state and the military in maintaining a consensus about the war, combined with the erosion caused by it. The high number of deserters and draft evaders46 may have several explanations, such as: a) the diminished capacity of the military structures and authorities in controlling the young men who were drafted into the war; b) the pervasiveness of family and community channels and networks within the context of European emigration, facilitating the process of migration and social insertion in these other countries; or c) the growing moral and social exhaustion of a long, drawn-out war waged far from the communities of origin of the Portuguese mobilized to fight in it.

However, understanding the refusal to participate in the war is a complex problem. Far from focusing simply on the quantification of deserters and draft evaders, we must make a detailed study of the specific scenarios in which the war took place and the diversity of paths, military categories, contexts, and intentions in play. We still need to compile a comprehensive chart of the disobedience episodes for which there exist military records. In fact, the data thus gathered could also shed important light on the erosion of military discipline, both within the military units sent from metropolitan Portugal and among the locally conscripted soldiers. Our own contribution seeks to chart, both quantitatively and qualitatively, the cases of disaffection that occurred among the Portuguese troops during the colonial war, while assessing their relevance and examining their multidimensional nature.

Appendix

Chart 1: Number of Deserters from the Portuguese Armed Forces, 1961-1973

![Table 1: Draft Evaders from the Portuguese Armed Forces, 1967-1969 (Source: PT/AHM/FO/006/J/24 cx. 604, 22 – “Amnistia aos emigrados clandestinos” [Amnesty for Clandestine Emigrants])](3-2.png)

Table 1: Draft Evaders from the Portuguese Armed Forces, 1967-1969 (Source: PT/AHM/FO/006/J/24 cx. 604, 22 – “Amnistia aos emigrados clandestinos” [Amnesty for Clandestine Emigrants])

![Table 2: Defaulters at Portuguese Military Inspection, 1961-1972 (Source: Relatórios Anuais de Recrutamento. Resenha Histórico-Militar das Campanhas de África [Annual Draft Reports. Historical-Military Review of the African Campaigns] (1961-1974), Estado-Maior do Exército [Army Staff], volume 1. Enquadramento Geral. Lisbon, 1988, p. 258. )](3-3.png)

Table 2: Defaulters at Portuguese Military Inspection, 1961-1972 (Source: Relatórios Anuais de Recrutamento. Resenha Histórico-Militar das Campanhas de África [Annual Draft Reports. Historical-Military Review of the African Campaigns] (1961-1974), Estado-Maior do Exército [Army Staff], volume 1. Enquadramento Geral. Lisbon, 1988, p. 258.47)

References

Almeida, João Miguel (2008). A Oposição Católica ao Estado Novo. 1958-1974. Lisboa: Edições Nelson de Matos.

Aranha, Ana and Ademar, Carlos (2018). Memórias do Exílio. Lisboa: Parsifal.

Bebiano, Rui (2002). “A esquerda e a oposição à guerra colonial”. In Rui de Azevedo Teixeira (ed.), A Guerra do Ultramar. Realidade e Ficção. Livro de Actas do II Congresso Internacional sobre a Guerra Colonial. Lisboa: Editorial Notícias.

Bebiano, Rui (2003). O Poder da Imaginação. Juventude, Rebeldia e Resistência nos Anos 60. Coimbra: Angelus Novus.

Bebiano, Rui (2006). “Contestação do Regime e Tentação da Luta Armada sob o Marcelismo,” Revista Portuguesa de História, 37, 65-104.

Bebiano, Rui (2016). “Experiência e memória da deserção e do exílio (como um prefácio).” In AAVV, Exílios. Carcavelos: Associação de Exilados Políticos Portugueses.

Cardeira, Fernando (2016). “A importância política da deserção.” In AAVV, Exílios. Carcavelos: Associação de Exilados Políticos Portugueses, 104-115.

Cardina, Miguel (2010). “The War Against the War. Violence and Anticolonialism in the Final Years of the Estado Novo.” In Bryn Jones and Mike O’Donnell (eds.), Sixties Radicalism and Social Movement Activism. Retreat or Resurgence? London: Anthem Press, 39-58.

Cardina, Miguel (2011). Margem de Certa Maneira. O Maoismo em Portugal (1964-1974). Lisboa: Tinta-da-China.

Cardina, Miguel (2018). “Deserção de Antigos Alunos Oficiais da Academia Militar.” In Miguel Cardina and Bruno Sena Martins (eds.), As Voltas do Passado. A guerra colonial e as lutas de libertação. Lisboa: Tinta-da-China, 189-195.

Castelo, Cláudia and Jerónimo, Miguel Bandeira (eds.) (2017). Casa dos Estudantes do Império: Dinâmicas Coloniais, Conexões Transnacionais. Lisboa: Edições 70.

Cordeiro, José Manuel Lopes (2017). “A polémica sobre a deserção durante a guerra colonial.” In Ana Sofia Ferreira, João Madeira and Pau Casanellas (eds.). Violência Política no Século XX. Um balanço. Lisboa: Instituto de História Contemporânea, 209-222.

Correia, Ricardo (2019). O meu país é o que o mar não quer e outras peças. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra.

Costa, Hélder (1980). Teatro Operário: 18 de Janeiro de 1934 / O Soldado. Coimbra: Centelha.

Cunha, J. da Luz, Arriaga, Kaúlza de, Rodrigues, Bethencourt and Marques, Silvino Silvério (1977). África. A Vitória Traída. Braga: Intervenção.

Estado-Maior do Exército (1988). Resenha Histórico-Militar das Campanhas de África (1961-1974). Lisboa: Estado-Maior do Exército.

Exílios. Testemunhos de Exilados e Desertores Portugueses na Europa (1961-1974) (2016). Carcavelos: Associação de Exilados Políticos Portugueses.

Exílios 2. Testemunhos de Exilados e Desertores Portugueses (1961-1974) (2017). Carcavelos: Associação de Exilados Políticos Portugueses.

Gomes, Carlos de Matos (2013). “A africanização na guerra colonial e as suas sequelas. Tropas locais—os vilões nos ventos da História.” In Maria Paula Meneses and Bruno Sena Martins, As Guerras de Libertação e os Sonhos Coloniais. Alianças secretas, mapas imaginados. Coimbra: Almedina, 123-141.

Glass, Charles (2013). The Deserters. A hidden history of World War II. USA: Penguin Books.

Grinchenko, Gelinada and Narvselius, Eleonora (eds.) (2018). Traitors, Collaborators and Deserters in Contemporary European Politics of Memory. Formulas of Betrayal. Switzerland: Palgrave MacMillan.

Guerra, João Paulo (1994). Memória das Guerras Coloniais. Porto: Afrontamento.

Madeira, João (2004). “As Oposições de Esquerda e a Extrema-Esquerda”. In Fernando Rosas and Pedro Aires Oliveira (eds.), A Transição Falhada. O Marcelismo e o Fim do Estado Novo (1968-1974). Lisboa: Editorial Notícias, 91-135.

Madeira, João (2013). História do PCP. Lisboa: Tinta-da-china.

Martins, Susana (2018). Exilados Portugueses em Argel. A FPLN das origens à rutura com Humberto Delgado. Porto: Afrontamento.

Melo, Daniel (2015). “Circulação, apropriação e actualidade das ideias contra a Guerra Colonial. Notas críticas de problematização”. In Cultura. Revista de História e Teoria das Ideias, 34, 249-290.

Pereira, José Pacheco (2013). As Armas de Papel. Publicações periódicas clandestinas e do exílio ligadas a movimentos radicais de esquerda cultural e política (1963-1974). Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores / Temas e Debates.

Pereira, Victor (2013). “La Cimade et les Portugais en France de 1957 à 1974: une aide sous le signe des guerres coloniales,” in Marianne Amar, Marie-Claude Blanc-Chaléard, Françoise Dreyfus-Armand and Dzonivar Kevonian (eds.), La Cimade et l’accueil des réfugiés. Identités, répertoires d’actions et politique de l’asile, 1939-1994. Nanterre: Presses Universitaires de Paris-Ouest, pp. 141-155.

Pereira, Victor (2014). “Les réseaux de l’émigration clandestine portugaise vers la France entre 1957 et 1974,” Journal of Modern European History, 12, 1, pp. 107-125.

Pereira, Victor (2015). “La société portugaise face aux guerres coloniales (1961-1974),” Cahiers d’histoire immédiate, 48, pp. 35-58.

Pimentel, Irene Flunser (2014a). História da Oposição à Ditadura. 1926-1974. Porto: Figueirinhas.

Pimentel, Irene (2014b). “Desertar ou ir à guerra? Há mais de 40 anos, muitos jovens portugueses confrontaram-se com esta difícil alternativa.” In Irene Pimentel [online]. Available at: http://irenepimentel.blogspot.com/2014/04/desertar-ou-ir-guerra-ha-mais-de-40.html [consulted on January 5, 2018].

Quemeneur, Tramor (2011). “Refuser l’autorité? Étude des désobéissances de soldats français pendant la guerre d’Algérie (1954-1962).” In Outre-mers, Nr. 98, pp. 57-66.

Raposo, Eduardo M. (2019). Cláudio Torres. Uma vida com história. Porto: Edições Afrontamento.

Resenha histórico-militar das campanhas de África (1961-1974), vol. I. Enquadramento geral. (1998). Lisboa: Estado Maior do Exército.

Scott, James C. (2013). A Dominação e a Arte da Resistência. Discursos Ocultos. Lisboa: Letra Livre.

Simon, Catherine (2011). Algérie, les années pieds-rouges. Paris: La Découverte.

Strippoli, Giulia (2016). “Colonial War, Anti-colonialism and desertions during the Estado Novo. Portugal and abroad.” In Marín Corbera, Martí; Domènech Sampere, Xavier and Martínez i Muntada, Ricard (eds.), III International Conference Strikes and Social Conflicts: Combined historical approaches to conflict. Barcelona: CEFID-UAB, pp. 430-444.

Veloso, Jacinto (2007). Memórias em Voo Rasante. Papa-Letras.

Notes

1 The present article was written in the context of the following projects: “CROME – Crossed Memories, Politics of Silence. The Colonial-Liberation War in Postcolonial Times,” financed by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (StG-ERC-715593); “ECHOES – Historicizing Memories of the Colonial War,” financed by the Foundation for Science and Technology (IF/00757/2013); “Os desertores: recusar a guerra, combater o colonialismo” [“The deserters: refusing war, fighting colonialism”], financed by the Foundation for Sustainability and Innovation and based at the University of Coimbra’s Center for Social Studies and 25 April Documentation Center; “De Rabat a Argel: caminhos cruzados entre a luta antifascista e a luta anticolonial (1961-1974)” [“From Rabat to Algiers: where the antifascist and the anticolonial struggles cross paths”], financed by the Foundation for Science and Technology (BPD/117494/2016). The authors would like to acknowledge the helpful comments and suggestions made by the anonymous reviewers. Translation: João Paulo Moreira.

2 Centro de Estudos Sociais da Universidade de Coimbra, CES, Portugal. E-Mail: [email protected]

3 Centro de Estudos Sociais da Universidade de Coimbra, CES, Portugal. E-Mail: [email protected]

4 Without claiming to be exhaustive, we can say that the question of desertion has been addressed in books and articles not only about the whole question of the opposition to the war, its validity, or its lack of legitimacy (Bebiano 2002 and 2006; Madeira 2004; Cardina 2010 and 2011; Pereira 2013; Pimentel 2014a; Pereira 2015; Strippoli 2016; Cordeiro 2017), but also, and more specifically, about the dynamics of migration, international support networks, and the experience of exile (e.g. Pereira 2013 and 2014; Martins 2018). As far as personal memoirs are concerned, mention should be made—in addition to the accounts disseminated through social media—of a number of books on the subject of exile that broach the issue of disobedience and the refusal of war (see, for instance, Aranha and Ademar 2018; Raposo 2019). A number of cultural representations have also addressed the theme in recent times, as is the case with Rui Simões’ 2012 film Guerra ou Paz (“War or Peace”) or Ricardo Correia’s book of plays (Correia 2019).

5 See, for instance, the establishment, in November 2015, of the AEP 61-74, Associação de Exilados Políticos Portugueses (Association of Portuguese Political Exiles). This association has published two books, Exílios (2016) and Exílios 2 (2017), that bring together the personal testimonies of deserters and draft evaders from the colonial war, as well as co-organizing (with Centro de Estudos Sociais da Universidade de Coimbra, Centro de Documentação 25 de Abril da Universidade de Coimbra, Centro em Rede de Investigação em Antropologia e Instituto de História Contemporânea da Universidade Nova de Lisboa) the colloquium O (as)salto da memória: história, narrativas e silenciamentos da deserção e do exílio, which took place in Lisbon on October 27, 2016. Also worth mentioning are the activities of the Mémoire Vive association, which seeks to bring to light alternative and subaltern memories of Portugal’s presence in France, thereby also conferring greater visibility to the memory of desertion and the refusal of war.

6 “Refuse to embark, and if you are unable to do so, refuse to use your weapons against the Angolan people, thwart the repressive orders directed against Angola’s patriots, turn your weapons, if need be, against those who would make you killers of patriots and of defenseless men, women and children.” “Abaixo a Guerra Colonial!” [Down with the Colonial War!], Avante!, Nr. 300, May, 1961.]

7 “Crescem as Deserções e Protestos contra a Guerra Colonial” [Increase in Desertions and Protests Against The Colonial War], Avante!, Nr. 362, December, 1965; “Contra as Guerras Coloniais as Deserções Continuarão” [Desertions Against Colonial War To Continue], Avante!, Nr. 370, September, 1966.

8 “Resolução sobre Deserções” [Resolution on Desertions], Avante!, Nr. 382, September, 1967.

9A different view was held by the URML [Unidade Revolucionária Marxista‑Leninista—Marxist-Leninist Revolutionary Unity], for whom desertion amounted to an “individualistic and opportunistic attitude” that “necessarily [led] to the loss of members who might otherwise be useful to the Proletarian Revolution.” “A Guerra Colonial e a Luta Revolucionária no Exército” [The Colonial War and the Revolutionary Struggle within the Army], Folha Comunista, Nr. 2 (special issue), 1971.

10The Manifesto ao Soldado [“Soldier’s Manifesto”] stated it clearly: “When you do desert, try by any possible means to expropriate weapons, explosives, uniforms, documents, maps, etc… If you have a revolutionary friend whom you totally trust, hand over those materials to him. If not, make sure you bury them, carefully protecting them from humidity, or hide them in a safe place: should the revolution need them, the weapons will be there, ready for use.” “Soldados!” [Soldiers!], O Grito do Povo, Nr. 3, April, 1973.

11“Os Comunistas e a Questão Colonial: a guerra colonial e a revolução proletária” [The Communists and the Colonial Question: the Colonial War and the Proletarian Revolution], Estrela Vermelha, Nr. 13, October, 1972.

12“4 Milicianos Vítimas da Máquina Militar Colonialista-Fascista” [4 Non-Career Officers Fall Victim to the Colonialist-Fascist Military Machine], Luta Popular, Nr. 4, May/June, 1971.

13“A oposição contra Salazar acha que uma Revolução Armada é o único Caminho que resta a Portugal” [The opposition to Salazar believes that Armed Revolution is the only way left for Portugal”]—an article by John K. Cooley, the special correspondent for The Christian Science Monitor in Casablanca (which included statements by Fernando Piteira Santos), June 1, 1963. ANTT, PIDE/DGS – Frente Patriótica de Libertação Nacional, SC CI (2) 1353, Pt 2.

14“Como Resistir à Guerra” [How to Resist the War], Passa Palavra, unnumbered, January, 1967.

15“Press statements by non-career second lieutenant Manuel José Fernandes Vaz and non-career sergeant Fernando Fontes, two deserters from Portugal’s colonial army stationed in Guinea,” Conakry, November 21, 1963. Private Archive of José Hipólito dos Santos.

16Supintrep Nr. 62, 1-31/1/1970, 2ª Rep. do EME [2nd Bureau of the Army Staff], March 5, 1970. PT/AHM/FO/007/A/19/Cx. 39, 4.

17Letter from the Army Minister’s Head of Cabinet to the Director-General for Security, April 14, 1970. ANTT, PIDE/DGS, SC CI (1) 659 UI 1196, Pt 12.

18Letter from the Director-General for Security to the Head of the Bureau of the Army Minister’s Cabinet, Lisbon, April 28, 1970, and Notes from the Information Service Division, April 25, 1970. ANTT, PIDE/DGS, SC CI (1) 659 UI 1196, Pt 12.

19The genre was given life by the voice of such musicians as José Mário Branco, Sérgio Godinho, José Afonso, Adriano Correia de Oliveira, Tino Flores, and Luís Cília. Flores and Cília recorded songs that advocated desertion.

20There were instances of the refusal of war for religious reasons, as was the case with Jehovah’s Witnesses. Subsequent military documents indicate that “among the defaulters, the number of those who cited reasons of conscience for not showing up for the medical inspections was negligible: only 23 in 1969, for example” (Resenha 1998: 235). No indication is given as to the reasons invoked. It is important to bear in mind that Portuguese law did not allow for “conscientious objector” status at that time.

21Article 30 of Law Nr. 1961—Law on Conscription and Military Service, of September 1, 1937, as amended by Law Nr. 2034, of July 18, 1949. A new Military Service Law came into force in 1968, but it maintained the previous categories (Law Nr. 2135, of July 11, 1968).

22Twice as long if the offender had been serving in a given unit for less than three months. Article 163 of the Code of Military Justice, promulgated by Decree Nr. 11292, of November 26, 1925, whose provisions relating to desertion—articles 163 to 176 of Section VIII, Title II of Book I—were amended by Decree-Laws Nrs. 33493, of January 11, 1944, and 41752, of July 23, 1958. Slight changes were also introduced in 1965 by Decree-law Nr. 46206, of February 27.

23Articles 164, 165, and 166 of the Code of Military Justice, Idem.

24Cooperation among the police forces outside the strictly military sphere is confirmed not only by the lists of detentions made by those forces and mentioned in the Supintreps [Supplementary Intelligence Reports] of the Army Staff’s 2nd Bureau, but also, as far as the political police were concerned, by the arrest warrants published in their administrative orders. The political police also opened a personal file for each soldier, whether this person was a deserter or a draft evader, whose capture had been requested by the military authorities.

25Thus, during peacetime, non-commissioned officers and privates faced a minimum sentence of two to three years in a military prison if they reported voluntarily to the competent authority and three to four years if they were captured, but, in times of war, these sentences were increased to three to four years and five to six years, respectively. As far as officers were concerned, the detention time was four years and one day to six years during peacetime and six years and one day to eight years in times of war, and, of course, there was always the additional penalty of dismissal. Code of Military Justice, articles 170 and 173.

26See for example the monthly reports (Supintreps) of the Army Staff’s 2nd Bureau. The reports recorded the subversive or potentially subversive activities of both civilians and members of the military impacting directly on the Armed Forces’ morale and discipline. PT/AHM/FO/007/A/19/Box 39, 1 to 6; PT/AHM/FO/007/A/19/Box 40, 7 and 8; and PT/ADN/F02/SC002/64.

27PT/ADN/F02/SC002/64 – Supintrep Nr. 14, January 1-31, 1966, 2nd Bureau of the Army Staff, February 14, 1966.

28The calculation of the total figure for deserters was based on various types of documentation—mostly military reports, memos from the Military Regions, and administrative orders from PIDE/DGS [political police]—obtained from the Military History Archive, the National Defense Archive, and the Torre do Tombo National Archive. This estimate does not include either the special units created in the various African territories or the native militias, whose members, in both cases, were locally recruited. Sources for mainland Portugal and the islands of the Azores and Madeira: “List of Military Personnel Mobilized by the GML [Lisbon Military Government] who until August 1961 missed boarding their vessel on the way to overseas service, thus becoming deserters”, n/d [1961], CI (1) 1070, UI 1209, folder 1; PIDE administrative orders, 1961-1969; Supintrep Nr. 85, Annex A (Illegitimate Absences and Desertions), February 28, 1972 (for the years 1970-1971), PT/AHM/FO/007/A/19/ Box 39.6; Supintrep Nr. 12/72, Annex A (Illegitimate Absences and Desertions), February 16, 1973 (year 1972), PT/AHM/FO/007/A/19/Box 40.7; and Supintrep Nr. 12/73, Annex A (Illegitimate Absences and Desertions), February 22, 1974 (year 1973), PT/AHM/FO/007/A/19/Box 40, 8. Sources for Angola: Listings of deserters and illegitimate absentees, with updates, sent to the General Secretariat of National Defense (for the years 1961-1964, 1970, and October to December, 1973); and Perintreps from the Headquarters of the Military Region of Angola and the Command-in-Chief of Angola’s Armed Forces (for the years 1965-1969 and 1971 to September, 1973). Sources for Guinea: Perintreps from the Independent Territorial Command of Guinea and the Command-in-Chief of Guinea’s Armed Forces. Sources for Mozambique: Perintreps from the Headquarters of the Military Region of Mozambique/Command-in-Chief of Mozambique’s Armed Forces.

29One example, left outside our figures: in September 1973, the Portuguese Navy frigate Almirante Magalhães Correia, engaged in a NATO mission, stopped in Denmark, and five Portuguese crew members deserted. The following day, they went to Malmo, in Sweden, where they received the support of the Portuguese Deserters’ Committee of Malmo/Lund.

30The starting date for counting the number of deserters was the outbreak of the wars (1961 in Portugal and Angola, 1963 in Guinea). In the case of Mozambique, there are no data for the period before 1966. The gaps in information for the first four months of 1974 are the reason this time period has been excluded from the present analysis. This option omitted, among others, cases such as the desertion of the air force pilot Jacinto Veloso in Mozambique (see Veloso 2007).

31In fact, according to Supintrep data, from 1970 to 1973, the number of actual desertions accounted for between 42 and 51 percent of all unlawful absences recorded. During that period, the share of absentees who presented themselves voluntarily to the authorities ranged from 28 to 36 percent, and from 18 to 24 percent in the case of those who were captured. Although many of these, especially in the first group, might not have meant to desert, this must surely have been the intention of quite a few. But as their exact number is impossible to determine, it is best to omit these cases.

32For example, in early 1969, the unit commanders in Mozambique were still urged to provide timely and systematic information on instances of unlawful absences and desertions so that rapid action could be undertaken to stop the offenders and cut the losses. Perintrep Nr. 04/69, for the period 20-27/01/1969. PT/ADN/002/02/004/001/Cx 44.

33Letter from the Army Chief of Staff of the Command-in-Chief of Angola’s Armed Forces to the Secretariat of National Defense, February 17, 1973. PT/ADN/F05/SR57 – Desertores /Cx 283, processo 38.

34Radio communications from Mozambique’s Command-in-Chief to the Public Information Service of National Defense (SPIFA), January 27, 1972, February 5, 1972, January 30, 1973 and February 1, 1973. PT/ADN/F05/SR57 – Desertores de Moçambique [“Mozambique Deserters”] (1972) / Cx 282, 36 and PT/ADN/F05/SR57 – Desertores de Moçambique (1973-1974) / Cx 283, 42g.

35A perfect illustration of this can be seen in the case of the non-career officer José Moura Marques. Having been stationed in Angola since December 1962, he went back to metropolitan Portugal on leave in early May of the following year. During this leave period, he requested permission to travel to London to attend a soccer match. The request was granted, but then his leave expired on June 3 and he was considered a deserter on the 13th of the same month. PT/ADN/F05/SR57 – Desertores (1961-1971) / Cx 273, 1. The Code of Military Justice stipulated that if the serviceman was on leave or in the reserve, the period for him to be classified as a deserter would be extended to ten days. Article 163 of the Code of Military Justice.

36The arrest of Portuguese deserters—whether recruited in metropolitan Portugal or in the African provinces—by the authorities of the countries neighboring the theaters of operations was often mentioned in the documents we analyzed.

37This concern with “subversive” propaganda was, in fact, a constant one, especially when it divulged the accounts of deserters or questioned Portugal’s colonial policy. Perintrep Nr. 15/69, for the period 07-14/04/1969. PT/ADN/Fundo 002/ Secção 02/Série 004/SSR 001/ Caixa 44.

38As early as 1964, a report from Luanda described the barracks atmosphere among the “black troops” as being conducive to desertion. The racist overtones of the report hinted at a pervasive “false peace:” “The number of desertions continues to rise. There have always been desertions—even in the old days of false peace. But, in recent times, their number has greatly increased, and this is a cause for concern. Something is very wrong. Could it be that the enemy’s propaganda is beginning to have an influence on the black troops? There have been desertions in the larger units, and we know from experience that the blacks, who are accustomed to the quiet of the jungle, greatly dislike the labyrinth and the dizzying din of the RIL [Luanda Infantry Regiment] and other large units.”

39Such was the case, for example, with private Carlos Alberto Rocha. After being sent to Mozambique in October 1964 and wounded in combat on June 5, 1966, he was admitted to the Nampula Military Hospital and later evacuated to the main Military Hospital in Lisbon, where he had his right hand amputated. Lacking support and feeling “very disoriented,” he finally absented himself unlawfully. He became a deserter on September 25, 1966, and presented himself voluntarily on October 7 of the same year. After being tried and granted an amnesty, he deserted again on January 5, 1967, only to be captured and handed over to the military authorities by the GNR [the non-urban police force] on April 13. Held under arrest during the proceedings—a treatment reserved for deserters who did not present themselves voluntarily—and denied his request to be released pending trial, he deserted once more on October 23, 1967, and then presented himself again in December of that year. Despite the efforts made to amend the Code of Military Justice in order to cover cases such as this, a Statutory Order of the Minister for the Army, dated June 25, 1968, referred the matter to a “future global revision of military criminal laws.” PT/AHM/FO/006/J/24 cx. 605, 55, “Desertores—situação de um soldado” [Deserters—A Soldier’s Predicament].

40Confidential Note Nr. 478-277C, May 3, 1968. PT/AHM/FO/007/A/10/Cx. 27, 9, Proc. 1.101.7, 1968.

41There are no figures available on the situation in the African territories—in the case of what was known as “local recruitment”—although some of the data we collected suggests that there were difficulties in terms of securing attendance of the military inspection and conscription in general. See the episode in Mozambique involving forty-one recruits described as illegitimate absentees: “All but four of these privates come from the Municipalities of Savié and Maputo and, for the most part, they worked in [South Africa, but] happened to be back in their homes when they were recruited. Their respective AADMs had a difficult time recruiting them and all the men had to be kept under guard day and night until they were handed over to the units to which they had been assigned.” PER 37/69, for the period 8-15/09/1969. PT/ADN/Fundo 002/ Secção 02/Série 004/SSR 001/ Caixa 45.

42Estudo sobre Problemas de Recrutamento, 1.ª Rep. do EME [1st Bureau of the Army Staff], Lisbon, 1968.

43Decreto-lei [Decree-Law] 48.783. Diário do Governo, Nr. 300/1968, 1.º Suplemento, Série I, December 21, 1968.

44Decreto-lei [Decree-Law] 48.783. Diário do Governo, Nr. 34/1969, Série I, February 1969.

45“Amnistia aos emigrados clandestinos” [Amnesty for clandestine emigrants], PT/AHM/FO/006/J/24 cx. 604, 22.

46This is more than, for example, the 1% of deserters from the war in Algeria (Quemeneur 2011), although we have to bear in mind that we are dealing with a different kind of war and with types of disaffection that are not entirely similar. For a journalistic analysis of desertion in World War II, see Glass, 2013. For an analysis of the figure of the deserter viewed under the framework of the categories of treason and heroism, including an analysis of a number of cases, see Grinchenko and Narvselius, 2018.

47The percentage of defaulters for the year 1971, erroneously given as 20.3%, has been corrected. The reason for this reduction in value is not clear, but it may partly be due to an explanation given to Ana Cristina Pereira by Victor Pereira. According to this historian, in 1971, France promised Portugal that it would prohibit the entry of young people under 21 years of age. Although the French failed to comply with the agreement, for some time at least, a number of young men may have abandoned the idea of emigrating, believing that they would not be allowed to enter the country. Ana Cristina Pereira (2015), “O militar que chegou de táxi à revolução” [The soldier who took a taxi to the revolution], in Público, April 25, 2015.

Received for publication: 04 January 2019

Accepted in revised form: 15 January 2020

Recebido para publicação: 04 de Janeiro de 2019

Aceite após revisão: 15 de Janeiro de 2020

Copyright

2019, ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH, Vol. 17, number 1, June 2019