|

WAR OF THE SPANISH SUCCESSION, 1702

QUEEN ANNE'S WAR AND THE "GREAT DESIGN"

In 1709 the British government finally agreed, in cooperation with the New England colonies and New York, to mount an expedition on Port Royal, Nova Scotia, and Quebec. But this expedition, the "Great Design," had to be cancelled, disappointing New Englanders who had made heavy outlays in preparation, and also the Five Nations, especially the Mohawks, whose allegiance to the British cause now seemed in jeopardy. When Sir Francis Nicholson, career soldier and former governor of Virginia and Maryland, went to England in February, 1710, to plead the New England case for invasion he was accompanied by four "Indian Kings," whose rousing welcome by London society served to encourage Queen Anne and her ministers to revive the proposed plan. A year later a joint British land and sea campaign was launched, with attacks planned on Montreal and Quebec. Although experienced pilots with knowledge of the St. Lawrence River were lacking, as well as adequate supplies, it was decided to risk the venture anyway. In August, 1711, the invading force entered the St. Lawrence River, but as the fleet made their way toward Quebec they were enveloped by fog. Unable to sight land and buffeted by confusing currents, eight transports were wrecked and 884 men died. The commander, Admiral Hovenden Walker led the remaining ships back to England in disgrace, abandoning the "Great Design."

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Victory Will Come

23. Peter Pelham, Cottonus Matherus, Boston, 1727. (Restrike by Joseph Sabin, 1860).

Like Israel engaging against Benjamin, it may be we saw yet but the beginning of the matter; and that the way to Canada now being learnt, the foundation of a victory over it might be laid in what had already been done.nce,

The Phips expedition of 1690 was the first substantial New England operation against Canada, and although it failed, many, like Cotton Mather, perceived that it would lead to future success because the troops had been able, without any interference from the enemy, to reach the ramparts of Quebec. |

|

|

New England Humiliated at Port Royal, 1707

24. Cotton Mather, The deplorable state of New-England, by reason of a covetous and treacherous governour, and pusillanimous counselors … To which is added, an account of the shameful miscarriage of the late expedition against Port-Royal, London, 1708.

The years following the defeat of the Phips expedition saw an escalation of New England interest in mounting another attack on the French in Nova Scotia and Quebec, which was fueled by continuing French and Indian attacks on English frontier settlements. In 1707 Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island provided about 1,000 men and twenty-five vessels for an expedition to attack Port Royal in Acadia. Although the French garrison had fewer men, it held off the attackers until reinforcements arrived and New England experienced defeat once again. Angry voices, such as Cotton Mather's, (whose ability to craft a title is truly impressive) were raised in condemnation of the perceived mismanagement of the expedition. |

|

|

French Victory at Port Royal, 1707

25. "Le libraire au lecteur." In: Diereville, Relation du voyage du Port Royal de l'Acadie, Rouen, 1708.

This addendum to Diereville’s account reprints a news sheet item of February 25, 1708, celebrating the Acadian’s victory over New England forces. |

|

|

Mather's Lament for the Abducted

26. Cotton Mather, Duodeccenium luctuosum. The history of a long war with Indian salvages, and their directors and abettors; from the year 1702, to the year, 1714, Boston, 1714.

" To think of it; that we should still have some scores of our people, enchanted and enslaved, in the idolatries of Canada, and so held in chains of darkness by the frauds, and cheats, and chicaneries of the French priests."

|

|

|

Maintaining Order in Boston

27. Postscript. [London, 1711.]

Boston was the headquarters for gathering together the men and supplies for the sea arm of the failed 1711 invasion, which was to attack Quebec via the St. Lawrence River. The bustle of activity and the large numbers of men gathered together in Boston created a situation ripe for the spread of rumor and anxiety. A concern to maintain order and discipline led to the publication of notices such as this one, detailing the punishments for aiding and abetting desertion among the soldiers and sailors of the expedition. |

|

|

Expedition in Disarray

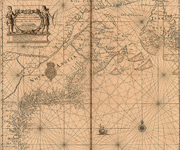

28. "A new chart of the sea coast of Newfound land, new Scotland, new England." In: The English Pilot. The Fourth Book, London, 1706.

Adding to the problems caused by fog and a lack of pilots experienced in St. Lawrence River navigation, there was also the issue of inadequate cartographic information. The chart of the St. Lawrence shown here is an example of what was available to British seamen at the time. It is plain that the lack of specific information about soundings and currents and the small scale and general nature of the chart made it especially important to have knowledgeable pilots to guide the fleet. |

|

|

Picking up the Pieces

29. Jeremiah Dummer, A letter to a noble lord, concerning the expedition to Canada, London, 1712.

The situation of that country gives the people an opportunity to invade all the British colonies when-ever they please. … And as the French are on the back of us, so the Indians are behind them, who with their united force often fall upon the English, and may be able in time (if not extirpated) to drive 'em into the sea.

The 1711 British naval expedition against Quebec has been considered one of the most inglorious operations in British military annals. It ended Admiral Hovenden Walker's naval career and gave rise to spirited debate. Here, Jeremiah Dummer sets out to answer two recurring questions about the debacle. First, would the campaign have been worth the effort and expense even if it had been successful (he says yes); and, second, where should the blame be laid for its failure. In reply to this last question Dummer found it necessary to answer the charge that the failure was New England's fault. Rumor had it that there had been notable and criminal lack of enthusiasm for the venture among Boston merchants who profited from trade with the enemy and dragged their feet in gathering provisions for the troops. |

|

|

The Four Indian Kings

When Sir Francis Nicholson, career soldier and former governor of Virginia and Maryland, went to England in February, 1710, to plead the New England case for invasion of Quebec, he was accompanied by four "Indian Kings" with various degrees of connection to the Iroquois confederacy who traveled with him as a kind of diplomatic entourage. They were not the first Indians to visit Britain, but the "Four Indian Kings" were the first to be presented as possessing the authority of rulers in a European sense, and whose purposes were clearly diplomatic. It was not very easy to recruit Iroquois leaders for the trip. The confederacy council was dominated by neutralists who wanted to avoid the dangers of too-close alignment with either France or Great Britain, so there was little hope of finding volunteers among leading Indian sachems. Instead, the colonial organizers found supporters where they could and shamelessly falsified their credentials to make them "kings." The Indian "kings" immediately found a place in the imaginative life of Great Britain—they were feted and painted and stared at and memorialized in a variety of ways that created long-lasting, popular images of the event. |

|

|

John Verelst, Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow King of the Maquas, [London, 1710].

Sa Ga Yeath, also called Brant, was a pro-English Mohawk with no formal claim to a leadership position. |

|

|

John Verelst, Etow Oh Koam King of the River Nation, [London, 1710].

One of the "kings," also called Nicholas, was not an Iroquois at all. The River Nation was another name for the Mahicans, who were under the influence of the Mohawks, but not part of the confederacy. Etow Oh Koam may have been important later, but in 1710 was without status. |

|

|

John Verelst, Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row King of the Generethgarich, [London, 1710].

Ho Nee Yeath, also called John, was another pro-English Mohawk with no formal claim to leadership status. "Generethgarich" is apparently a reference to Canajoharie, a western Mohawk town in what is now New York State. |

|

|

John Verelst, Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row, Emperor of the Six Nations, [London, 1710].

Only one of the "kings" could possibly be described as a sachem, and that would be a stretch. Theyanoguin, whose Christian name was Hendrick, belonged to the council of the Mohawk tribe, but not to that of the Iroquois confederacy as a whole. Even among the Mohawks he was still, at the age of thirty, a minor figure and hardly an "Emperor." |

|

|

The Brave old Hendrick the great sachem or chief of the Mohawk Indians, [London, ca. 1740].

The identity of the man in this engraving is disputed. A Mohawk named Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row, also called King Hendrick, was presented to Queen Anne in 1710 as one of the so-called "Four Indian Kings" who traveled to London on a diplomatic mission. The common story has been that in 1744 he returned to England for an audience with King George II, at which time he had his portrait painted. The historian Alden Vaughan, however, argues that the engraving shown here was of different individual—Hendrick Theyanoguin—a Mohawk known for his activities during the Indian wars of the 1740s, for his speech to the Albany Congress of 1754, and for his death at the battle of Lake George in 1755. Vaughan believes that this man never traveled to England and the portrait (now lost) upon which the engraving was based was painted by an itinerant English or American artist in America. |

|

| |

Exhibition seen in Reading Room from september 2008 through

december 2008.

Exhibition prepared by Susan Danforth, Curator of Maps and Prints. |

|