| |

First Approaches

Ponce de León Discovers and Names North America

The conqueror of Puerto Rico obtained a license to hunt for slaves on the island of “Bimini,” north of Hispaniola. He landed instead on the North American mainland, claimed it for Spain, and called it Florida. The news of his 1513 discovery gradually made its way onto printed maps and into the general histories of Oviedo, Gómara, and Peter Martyr, who added the angle of a fountain of youth. |

|

| |

|

|

|

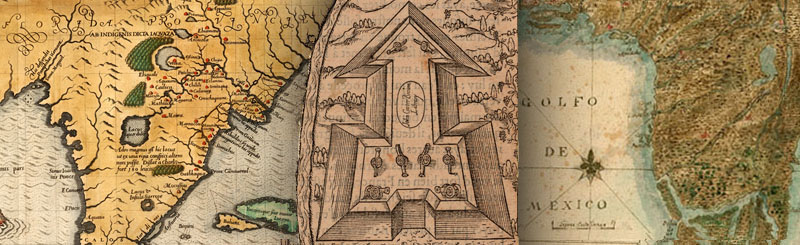

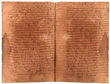

1. “Map of the Caribbean basin.” In: Pietro Martire d’Anghiera. Opera. Seville, 1511.

Few of the explorations preceding the settlement period were described at the time in separate narratives; rather they are most often recounted in general works such as the Opera by Peter Martyr, shown here. The map has intrigued researchers for years—it shows a land north of Cuba (Isla Beimini parte) before any documented explorations to the north had taken place. |

|

|

2. “Florida and the Caribbean basin.” In: Hernan Cortés. Praeclara Ferdina[n]di Cortesii de noua maris Oceani Hyspania narratio. Nuremberg, 1524.

Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) sent five long reports to Emperor Charles V, detailing his progress in the conquest of Mexico. This is the first Latin edition of his second letter, written in October 1520, where Cortés narrates the wars and alliances that took place on his way to the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan. The book also contains a woodcut map copied from the original sent by Cortés with his report. On a section showing the West Indies and the Gulf of Mexico, the words “La Florida” appear for the first time on a printed map. |

|

|

3. La carta uniuersale della terra ferma & isole delle Indie occide[n]tali. [Venice, ca. 1534].

Ramusio’s Summary of the general history of the West Indies was supposed to contain a map showing Spanish explorations in the New World to date. Only one copy of the book containing the map has been located, but over the centuries three other copies have turned up separately. This one came to the Library in 1929. The map by Ramusio is thought to have been based upon two official Spanish manuscript maps, the Ribero map of 1529 (probably based upon the padron real, the official map of Spanish navigation) and a Spanish pilot’s map of 1527, made shortly before the Narváez expedition (see no. 6). “Floride” is located at the top of the Florida peninsula. |

|

|

4. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés. La historia general de las Indias. Seville, 1535.

Oviedo was appointed official Chronicler of the Indies in 1532 and used the position to acquire every bit of information concerning the New World he could find, ultimately publishing a total of fifty books, or chapters. This edition of the Historia general includes only the first nineteen dedicated to the history of Columbus’ voyages and the Caribbean islands. Here, Oviedo includes an account of the 1513 expedition of Juan Ponce de León and a description of the alluring island of Bimini. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Costly Knowledge

For half a century, Spain’s every effort to establish a foothold in eastern North America was thwarted. With appalling loss of life, expedition after expedition was defeated by storms, food shortages, disease, defective intelligence, unrealistic expectations, Indian resistance, poor financing, and poorer leadership. The general histories were slow to convey the bad news. The hardships described in the Relacion of Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, one of the few survivors of the Pánfilo de Narváez expedition and the only first-person account of a Florida expedition to be published in the sixteenth century, did not inhibit the urge to find “other Mexicos” and “other Perus.” Best known of the Florida expeditions is that of Hernando de Soto, which yielded a fictionalized history and three primary relations, the texts of which have not yet been closely compared. |

|

| |

|

|

|

5. Bernal Díaz del Castillo. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva-España. Madrid, 1632.

Bernal Díaz del Castillo provided a first-person account of the expedition of Francisco Hernández de Córdoba to Yucatan in 1517 to capture Indian slaves to work agricultural land and mines in Cuba. This was the Europeans' first encounter with a civilization in the Americas that they recognized as being comparable to that of the Old World. The expedition did not go as planned, however, and the Spaniards came away empty-handed after suffering many injuries at the hands of the local population. On the return home to Cuba, the pilot, who had been with Ponce de León in 1513, took the party to the west coast of Florida to take on a supply of badly needed water. Once again they were attacked by the local native population and suffered further casualties. Córdoba died from his injuries shortly after the return to Havana. |

|

|

6. Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. La relacion. Zamora, 1542.

The Pánfilo de Narváez expedition of 1527 met its end when its land and sea forces failed to rendezvous at Apalache Bay, leaving the land forces stranded on the inhospitable Florida shore. The marooned explorers built rafts for escape, but these were destroyed and scattered by a hurricane. Cabeza de Vaca, treasurer of the expedition, found himself cast ashore on an island near Galveston, Texas. He survived nine years of wandering in the southwest of what is now the United States, reappearing in 1536 at Sinaloa in present-day Mexico. His narrative, shown here, united the east and the west—Florida and Lower California, the Atlantic and the Pacific—in contemporary Spanish thought, creating an emerging landscape of a New World empire. |

|

|

7. Gentleman of Elvas. Relaçam. Evora, 1557.

Disembarking in 1539 at what is now Tampa Bay, Hernándo de Soto began a reconnaissance march that zig-zagged through what is now Georgia, North and South Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Texas, and Oklahoma. By the time he died on the banks of the Mississippi River, De Soto and his men had spent three years in the wilderness on a trek that served to open the interior of the continent to exploration. Knowledge of the expedition derives primarily from this account by one of the participants, known only as the “Gentleman of Elvas.” |

|

|

8. Gentleman of Elvas. Virginia richly valued. London, 1609.

Although the Gentleman’s Relaçam in Portuguese attracted little attention at the time of its publication, the narrative became a factor in the growing English interest in American colonization when Richard Hakluyt translated it in 1609 with the enticing title, Virginia richly valued. In fact, Hakluyt’s several translation projects were part of a larger design to achieve his vision of advancing England’s national glory by awakening his countrymen to the benefits that exploration and conquest had brought to Spain. |

|

|

9. “Sobre los gastos de la florida.” In: Recopilacion de todas las cedulas. Manuscript. [compiled about 1584].

Angel de Villafañe was charged with establishing a settlement on the Gulf coast of Florida and opening an overland route to the northern outpost of Santa Elena (Port Royal, South Carolina). He appointed Tristán de Luna y Arellano to execute the plans, and in the summer of 1559 a landing was made at Pensacola Bay. But before the supplies could be unloaded, a hurricane struck and most of the ships and cargo were lost. Relief from Veracruz got the colony through the winter, but by spring the party was once again in dire straits. Luna’s leadership of the venture was deemed incompetent and Villafañe arrived to take charge of the situation. Those who wished to leave Pensacola could reutn with Luna to Mexico or join Villafañe’s expedition to Santa Elena. The area was not populated again by Europeans until 1698, when the Spanish retuned to fortify the bay of Pensacola. |

|

|

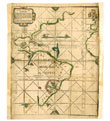

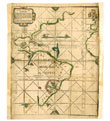

10. “Florida and the Caribbean.” In: Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas. Historia general. Madrid, 1601.

Herrera (d. 1625), an accomplished historian, was appointed Chronicler of the Indies by Philip II in 1586. In his history of the Indies he incorporated the greatest number of sources describing the Spanish experience in the Indies from 1492 to 1555 that had been amassed to that date. His Historia general included the Gulf region and Florida. This is one of the earliest appearances of “Tampa Bay” on a printed map. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Encroachment and Retaliation

French rivalry and reconnaissance: Coligny’s colonists

In the midst of the French wars of religion, with the blessing of Gaspard de Coligny (1519-1572), French nobleman, admiral, and Huguenot leader, a series of expeditions left France to establish a Protestant colony in Florida. News of the intrusion stirred Philip II to authorize, then partially finance, an expedition to “clean the coasts” of Lutherans. The ruthlessness with which its leader accomplished his mission became part of the anti-Spanish Black Legend, and all France took satisfaction in the dramatic retaliatory raid of Dominique de Gourgues, a Catholic corsair. This brief French occupation of the area also figured later as Great Britain, France, and Spain looked to past exploration and settlement to bolster their various claims to territory in what is now the southeast United States. |

|

| |

|

|

|

11. “Floridae Americae Provinciae.” In: Theodor De Bry, Grands voyages. Part 2. Latin. Frankfurt, 1603. |

|

|

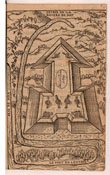

12. “Plan of Fort Caroline.” In: Coppie d’une lettre venant de la Floride. (Paris, 1565).

In 1562 Jean Ribaut led a group of Huguenots to Parris Island, South Carolina and erected a fort. The venture was short-lived—Ribaut returned to France for reinforcements and his colonists, unable to support themselves, followed a few months later. In 1564 a new expedition under the leadership of René de Laudonnière settled farther south and erected Fort Caroline near what is now Jacksonville, Florida. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, the Adelantado

Philip II’s chosen champion against the Huguenot intruders was Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, an Asturian who had risen to the rank of captain general in the armada. His contract with the Crown made him adelantado of Florida, which meant that he would receive the governorship of the colony if he could conquer, settle, and missionize it at his own expense. Arriving in Florida on August 28, 1565, he established St. Augustine thirty-five miles south of French Fort Caroline. The Spanish then marched north through a storm and surprised the fort, killing most of the defenders. |

|

| |

|

|

|

13. Bartolomé de Flores. Obra nuevamente compuesta. Seville, 1571.

This 376-line poem was written to celebrate the victory of Menéndez over the Huguenots. It’s the only contemporary, or nearly contemporary, printed account in Spanish of that destructive action against the French. But it is more than that, for as the poem goes on, the account of the battle merges gradually into a description of the Florida country, and it becomes clear that the poem is primarily a promotional tract to show that French Protestants had been effectively removed from that country, that the Indians were friendly, and that the land was a pleasant place to live. Menéndez was actively involved in colonizing activities and in 1571 (the same year as this publication) recruited and led a colony to Florida. |

|

|

14. Nicolas Le Challeux. Discours de l’histoire de la Floride. Dieppe, 22 May, 1566. |

|

|

15. Nicolas Le Challeux. Histoire memorable du dernier voyage aux Indes. Lyon: Jean Saugrain, 25 Aug. 1566.

Among the few survivors of the Spanish attack were René de Laudonnière, the expedition leader, Jacques Le Moyne, an artist, and Nicolas Le Challeux, the elderly carpenter who wrote this account of the destruction of the colony. This account of the massacre captured public attention in France, with two editions printed in two cities just months apart. The Dieppe edition contains a petition to the King requesting support for the widows and orphans of the men who died. |

|

|

16. “The true and last discoverie of Florida.” In: Richard Hakluyt. Divers voyages. London, 1582.

Thomas Hacket translated Nicolas Le Challeux’s account into English as part of Richard Hakluyt’s larger project to educate his countrymen about the advantages to be had by challenging Spain’s claims in the New World. Publicizing the Spanish attack on defenseless French Protestants in Florida was guaranteed to inflame anti-Spanish sentiment in England. |

|

|

17. René de Laudonnière. L’Histoire notable de la Floride. Paris, 1586.

Officially, Spain and France were at peace, so French revenge had to be the act of a single individual, in this case the pirate, Dominique de Gourgues. In April, 1568, with the assistance of Indian allies, he massacred almost all the Spaniards who had taken over Fort Caroline. Contemporary printed reports are almost non-existent due, no doubt, to the diplomatic embarrassment it would cause, but Laudonnière here reports on all the French expeditions, including the retaliatory attack by de Gourgues. |

|

|

To next section: Rivalries: Drake's Raid |

|

| |

Exhibition may be seen in THE Reading Room from january through

april 2013.

Exhibition prepared by Amy Turner Bushnell, Independent Research Scholar, and Susan Danforth, Curator of Maps, John Carter Brown Library. |

|

![]()