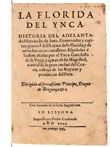

the florida indian in literature and art 23. Garcilaso de la Vega, El Inca. La Florida del Ynca. Lisbon, 1605. A mestizo of double nobility, Garcilaso (1539-1616), also known as “the Inca,” was the son of a Spanish soldier from a distinguished family and an Inca princess. He grew up in Cuzco, where he acquired a Renaissance education. In 1560 he left Peru, never to return, and settled in Córdoba, where he dedicated his life to study and writing and became a renowned Humanist. His history of the expedition of Hernando de Soto’s three-year exploration of what is now Florida and the Southeast was the first work published by a native-born American author. In this work, Garcilaso’s pride in his noble Indian background mingles strangely with a similar pride in his noble Spanish blood and the achievements of the conquistadors. Here, de Soto is exalted as a Renaissance hero of endurance and courage. Although based on eyewitness accounts, Garcilaso’s history is at times fanciful and prone to associations with Classical mythology. |

||

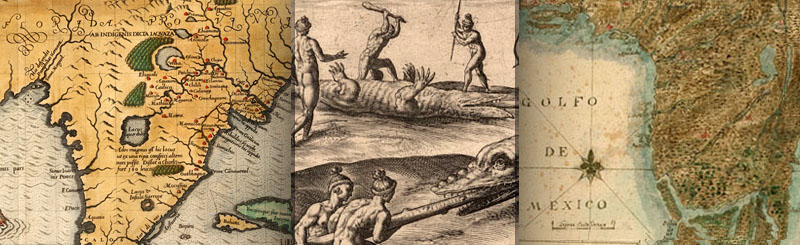

The Influential Imagery of Theodor de Bry The engravings shown here were produced by Theodor de Bry, who published Jacques Le Moyne’s account of the French attempt to establish a colony in Florida in 1565, which contained numerous engravings depicting the way of life and customs of the Timucuan Indians who lived in the area. During the course of the seventeenth century, the Timucuans were successfully christianized by Spanish missionaries, but they were virtually wiped out of existence in slaving raids armed by South Carolina in 1703 and 1704. The de Bry images are the only visual documentation of these peoples that we have, but it should be noted that they owe as much to European artistic sensibilities for depicting the human body as they do to the character of Le Moyne’s original drawings, which have been lost. |

||

24. [Outina’s military discipline when he goes to war.] In: Theodor de Bry. Grandes voyages. Part 2. German. Frankfurt, 1609. |

||

25. [Preparations for a feast.] In: Theodor de Bry. Grandes voyages. Part 2, German. Frankfurt, 1591. |

||

26. [Their way of killing crocodiles.] In: Theodor de Bry. Grandes voyages. Part 2. German. Frankfurt, 1591. The animal shown is an alligator; crocodiles are not native to Florida. |

||

Theodor de Bry's Engravings |

||

27. [The chief and his wife take a refreshing stroll.] In: Theodor de Bry. Grandes Voyages. Part 2. German. Frankfurt, 1591. |

||

28. Cesare Vecellio. Habiti antichi, et moderni di tutto il mondo. Venice, 1598. |

||

|

29. “Virginiae item et Floridae Americae provinciarum, nova description.” From: Gerard Mercator. Atlas. Amsterdam, 1619. |

|

|

30. “America with those known parts in that unknown worlde. 1612.” From: John Speed. A prospect of the most famous parts of the world. London, 1631. | |

| To next section: Spain's Pacification Policy: Conquest by Gospel | ||

Exhibition may be seen in THE Reading Room from january through Exhibition prepared by Amy Turner Bushnell, Independent Research Scholar, and Susan Danforth, Curator of Maps, John Carter Brown Library. |

![]()

| Images: "Map of Florida," Theodor de Bry, America, part 2 (1591); "[Killing of crocodiles]," Theodor de Bry. America, part 2. (1591); "Mapa topografico de la Florida lo dibuxo Pedro Diaz ano de 1769 por mandato Ilmo Senor Don Jose Puerto Llano y Canales" (1769). |

|---|