i. Saint-Domingue Before the Revolution |

||

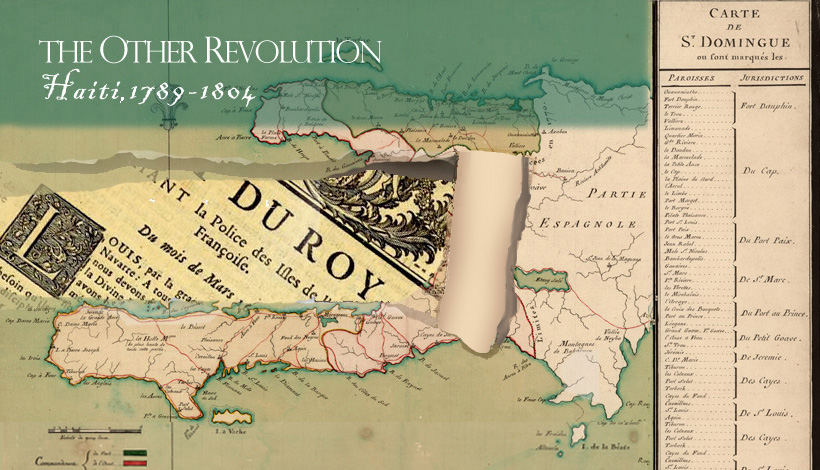

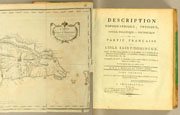

Sugar Plantations This 1770 map of Saint-Domingue shows the division of the colony into three administrative departments: north, west, and south. (What was called the “western” province at the time is perhaps more intuitively understood as the “central” region). At the right-hand side is a list of parishes and the ten lower-court jurisdictions into which they were grouped. The colony’s leading cities were Cap Français in the north (capital until 1750) and Port-au-Prince in the west (capital after 1750). As of 1789, the colony’s population consisted of about 30,000 white residents, a similar number of free blacks and people of color (also called “mulattoes), and roughly 465,000 (perhaps as many as 500,000) slaves of African descent. The most fortunate and powerful free people of color were prominent as coffee growers in the southern province and as military personnel in the north. |

||

Plan de quelques habitations du quartier de Limonade (Paris, ca. 1785). |

||

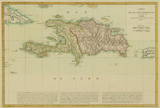

Frézier's map Frézier, a French military engineer and explorer, served in the colony of St. Domingue from 1719 to 1728. His map provides a wealth of topographical and navigational detail for the island and its surrounding waters. At upper left is an inset plan of the city of Santo Domingo, capital of the Spanish side of the island. Frézier dedicated his map to the Marquis d’Asfeld, director-general of French fortifications. |

||

Changing boundaries This engraved map by the Dutch cartographer P. L. de Griwtonn shows the island of Hispaniola circa 1760. At bottom is a detailed description of the French (western) and Spanish (eastern) sides of the island, a division that was formalized by the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697. The French colony of Saint-Domingue was divided into three provinces for administrative purposes: northern, western, and southern. |

||

Changing boundaries This revised state of Griwtonn’s map issued in 1801 shows the island of Hispaniola with its boundaries after Toussaint Louverture invaded Spanish Santo Domingo in1801 and divided the island into five departments. His control over the Spanish side proved to be short-lived, however. In June 1802 he was captured by an invading French army and deported to France. Leaders of the Haitian Revolution who followed Louverture continued to believe that for the island to remain independent it must be united under Haitian rule. Boundary issues were the cause of regular outbreaks of hostility between Haiti and what is now the Dominican Republic until a definitive border was agreed to by both parties in 1936. |

||

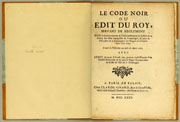

Code Noir (Black Code) The Code Noir (or “Black Code”) served as the basis of the law of slavery in Saint-Domingue and the other French plantation colonies. It was promulgated by Louis XIV in 1685 at the initiative of his recently deceased chief minister, Colbert, and reflected a combination of French Caribbean legal customs and Roman law principles. Despite sanctioning a rigorously punitive scheme for the discipline of slave labor, the Code Noir legalized manumission and prohibited the torture and mutilation of slaves by other than royal authority. It also granted freed persons the same rights and privileges as those enjoyed by whites. Predictably, these protections fell afoul of the planters and their representatives. |

||

Regulation to restore “good order” |

||

Black Spartacus in the Caribbean One of the few examples of antislavery sentiment in the pre-revolutionary French Atlantic world, the Histoire philosophique was also one of the great tracts of the Enlightenment, a mammoth multi-volume compilation of writings about European colonization whose authors included such luminaries as Diderot, Holbach, and Pechméja in addition to Raynal. In one of the Histoire’s more memorable passages, Raynal prophesied, twenty years before the event, the rise of a black Spartacus in the Caribbean – “Où est-il, ce Spartacus nouveau?” (“Where is he, this new Spartacus?”)– modeled on the great leader of a slave revolt in ancient Roman times. A perhaps apocryphal story has it that Toussaint Louverture later drew inspiration from this passage, but there is no question that it reflected widespread late colonial anxieties about the instability and viability of the plantation order. |

||

Law prohibiting inhumane treatment of slaves This landmark royal ordinance came at the end of decades of pragmatic concern that the “abuses introduced into the management of plantations located in Saint-Domingue” risked triggering a slave revolt of irreversible proportions. The new law prohibited the “inhumane” treatment of slaves by plantation managers and overseers, whether in the form of mutilation, the application of more than fifty lashes with a whip, or other methods likely to cause “different kinds of death.” The 1784 ordinance unleashed a torrent of criticism from the planters of Saint-Domingue, and the colony’s high courts refused to apply it until it was watered down. |

||

Coffee in St. Domingue The hills that rose above the plains of Saint-Domingue provided convenient sites for the layered terraces on which coffee beans could be grown. A significant number of the colony’s coffee plantations were owned and managed by people of color. Coffee’s importance to the French colonial economy grew dramatically in the period after the Seven Years’ War (1754-63). In this book published as the British occupation of the western and southern provinces of Saint-Domingue (1793-1798) was coming to an end, a white coffee planter named P. J. Laborie offered to share his expertise for the benefit of his British counterparts in Jamaica. The plate shown here illustrates how colonial coffee growers took advantage of the mountainous terrain, unsuited for sugar cultivation, that dominated the western and southern regions. |

||

The “science” of skin color What contemporaries called the “mixing” of races in Saint-Domingue occasioned a plethora of commentaries, nearly all white-supremacist and polemical in character, on the causes and consequences of the colony’s multiracial order. The most famous of these commentaries was by Moreau de Saint-Méry, the colonial jurist and historian whose writings on Saint-Domingue are still a major resource for contemporary scholars. In volume one of his Description, Moreau counted and categorized no less than 128 racial combinations in the colony. The “science” of skin color received one of its earliest formulations in this work, completed in 1798 after the author was exiled to the United States. It seems that Moreau was himself the father of a child by his free-colored mistress. |

||

| Exhibition prepared by: Malick W. Ghachem (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), guest curator, with assistance from Susan Danforth (Curator of Maps and Prints, John Carter Brown Library). |