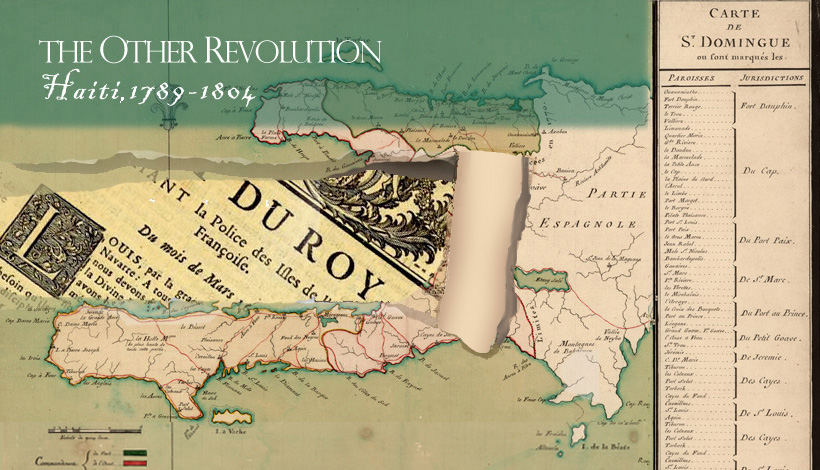

ii. the french revolution and the free people of color |

||

Cap Français “Vue de Cap Francais.” In Nicolas Ponce: Recueil de vues des lieux principaux de la colonie Françoise de Saint-Domingue (Paris, 1791). In this engraving of Cap Français, Ponce offers a panoramic view from behind the town’s prison, where captured fugitive slaves (among others) were held until they could be reclaimed by their masters. |

||

No colonial representation in the French Assembly The convocation of the Estates General in 1788 and 1789 opened the door to revolution in France. That event also had profound repercussions in St. Domingue. Like their metropolitan counterparts, the colonists (through their representatives) were eager to present their grievances to the king and nation, represented by the three estates of clergy, nobility, and all others (the “Third Estate”). In this letter to the so-called Assembly of Notables, a gathering of the first two estates only that met in the fall of 1788, the commissioners of Saint-Domingue insisted on the colony’s right to representation in the upcoming “assembly” of “the great family” that was France. However, the king’s formal convocation of the Estates in August 1788 had made no provision for colonial representatives to attend. |

||

Famine vs. mercantilist policies In the spring of 1789, as France was suffering from drought and poor grain harvests, the governor of Saint-Domingue (the Marquis du Chilleau) authorized the importation of foreign (i.e. , U.S.) flour. This decision violated the mercantilist policy known as the Exclusif, which required Saint-Domingue to obtain food supplies solely from the mother country. The Exclusif had been relaxed in 1784, in recognition of the reality that the United States and Saint-Domingue had become major trading partners. But Du Chilleau’s decision was still seen as a violation of royal law, and it led to his recall by the French Naval Minister. Here the Marquis de Cocherel (1741-1826), a deputy to the French National Assembly from the western province of Saint-Domingue, defended Du Chilleau with reference to the famine “now devastating” the colony. |

||

“All men are born free and equal” The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was approved by the National Assembly on August 26, 1789. Its Article 1 famously declared that “all men are born free and equal.” Nothing was said in the document itself about whether its terms would apply to the French colonies. The same month in which the Declaration was promulgated, representatives of the white planters and the gens de couleur of Saint-Domingue residing in Paris formed separate political clubs to advocate for their respective interests. In this pamphlet, the self-described “property-owning” free-colored representatives argued that the Declaration’s terms should apply to people of color as well as to whites. They also invoked the Code Noir provisions granting equal rights of citizenship to freed persons. |

||

Free blacks criticize free people of color The claims of the free people of color in 1789 were met not only by the predictable resistance and rejection by the white planter representatives, but also by parallel demands from the free black representatives. In another 1789 pamphlet published just before this one, the free blacks (calling themselves “American colonists”) criticized the free people of color for being of “mixed blood,” in contrast to their own supposed state of “pure blood.” Indeed, there is reason to wonder whether this rhetoric may not have been issued from the pen of an ally of the white planters in Paris. Here, an anonymous representative of the free people of color defends against the charge of racial impurity. |

||

Free people of color not welcome as equals Early 1790 was a time of great disarray in the capital of Port-au-Prince. Royal officials were fleeing the colony, garrisons were in mutiny and riots and lynchings had erupted. Councils and assemblies were convened, adjourned, and abandoned. Some wore white cockades supporting the king. In February the white planters of the western province called for a colony-wide assembly to meet at Saint-Marc in late March. Article IX of the call made it clear that free people of color were not welcome as equals. Just as has always been the case, Mulattos, Negroes, and other free people of color, will not be eligible to vote in the parish assemblies; but they can submit their questions to the selected deputies in each parish, and thus presenting them to the Colonial Assembly; they may, alternatively, apply to the same assembly through a single representative or patron whom they will choose from among white citizens. |

||

Vincent Ogé’s rebellion As soon as it became clear that none of the pre-existing colonial assemblies would allow free people of color to vote in the newly authorized local elections, a small and unsuccessful merchant living in Paris named Vincent Ogé (1756-1791), a free person of color, secretly returned to Saint-Domingue to organize an armed rebellion, reportedly with the aid of the British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson. Insisting that the National Assembly had implicitly authorized mulatto participation in the elections, Ogé joined forces with another free person of color named Jean-Baptiste Chavanne (1748-1791) to lead a rebellion in the northern province in October 1790. The uprising was quickly and brutally suppressed. Ogé and Chavanne were publicly executed on the wheel in Cap Français in February 1791. |

||

Petition for equality The repression of Ogé’s rebellion did not end the efforts of the free people of color to assert their rights to active citizenship in Saint-Domingue. In March 1791, Julien Raimond (1744-1801), one of the leaders of the free colored community in Paris, was one of the authors of this renewed appeal to the National Assembly. The petition called upon the Assembly to enforce its own March 1790 mandate that “all persons paying taxes in the islands” were entitled to vote in the local elections. The need to qualify as taxpayers may help explain why the free people of color so often stressed their slaveholding status during this period. |

||

Local legislative bodies formed The colonists did not wait for the arrival of the National Assembly’s March 1790 decree to form local legislative bodies in Saint-Domingue to deal with the new political context created by the French Revolution. They had already begun to form provincial assemblies as early as 1788 and 1789. In February 1790, the more conservative, “autonomist” planters decided to convoke a “general assembly” of Saint-Domingue in the name of the colony’s three provincial assemblies. In their “constitutional bases” of May 28, 1790, the Saint-Marc deputies (named after the town on the west coast in which they met) responded to the metropole’s authorization of local elections by insisting that only they could legislate for the colony’s internal regime, and by explicitly disqualifying non-whites from the privilege of active citizenship. In this pamphlet, one of the Saint-Marc deputies argues that the National Assembly implicitly surrendered its right to intervene in the colonies when it promulgated the Declaration of the Rights of Man. |

||

| Exhibition prepared by: Malick W. Ghachem (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), guest curator, with assistance from Susan Danforth (Curator of Maps and Prints, John Carter Brown Library). |