New England

Slavery and the Slave Trade in Rhode Island

> The Brown Family

and the Slave Trade:

The Voyage of the Sally

The Voyage of the Brig Sally

The Brown Family kept the most meticulous records of any mercantile firm in colonial America, much of which are preserved in the John Carter Brown Library. Not only did the Browns keep excellent records, they were scrupulous in preserving the records, which accumulated throughout two centuries. The Library acquired the bulk of the records by 1923 and holds a 700-page finding aid providing access to the papers. In particular, the Library holds the ship’s log of the brig Sally, which documents the disastrous slaving expedition examined in the online Voyage of the Slave Ship Sally, 1764–1765.

Nicholas Brown & Company needed capital in 1764 to buy supplies for their candle works, as well as for their newest venture, an iron furnace. [8] With slave labor in high demand throughout the Americas, an African voyage promised a quick and substantial profit. The initial venture with Carter Braxton, a Virginian merchant, [9, 10, & 11] fell through and the Brown brothers proceeded by themselves. In the end, they hired Esek Hopkins, a naval veteran of the Seven Year’s War (the French and Indian War in colonial North America) who would later be appointed commander-in-chief of the Continental Navy in 1775. [12]

![]()

![[8] Candle making](../Images/Thumbnails/Item8_thumb.jpg) |

[8] Candle making larger view

“Spermacoeti Candles Warranted Pure …,” Providence, [1764] The Brown family first made their money in candle works. In the early 1750s, Obadiah Brown set up a spermaceti candle factory. From there they moved onto building the Hope Furnace. Here we see an advertisement for their wares. |

![[9, 10 & 11] Potential Investor](../Images/Thumbnails/Item9_thumb.jpg) ![[9, 10 & 11] Potential Investor b](../Images/Thumbnails/Item10_thumb2.jpg) ![[9, 10 & 11] Potential Investor c](../Images/Thumbnails/Item11_thumb2.jpg) |

[9, 10 & 11] Potential Investor larger view

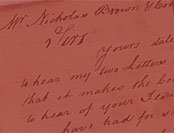

Carter Braxton to Nicholas Brown & Company, Virginia, October, 16, 1763 “. . . the whole of the voyage I should leave to you to conduct and you may begin to prepare if you please, but you will let me know the terms and everything relating to the voyage before the vessell sails. It ought to be forwarded so as to have the vessell here in May, because the negroes will sell better then, than later. The Gold Coast slaves are esteemed the most valuable and sell best. The prices of negroes keep up amazingly. They have sold from £30 to £35 sterling a head clear of duty all this summer I should not doubt of rendering such a sale if the negroes were well and came early . . .” Carter Braxton (1736–1797) was the son of a Virginia merchant-planter, and grandson of Robert “King” Carter, one of the wealthiest landowners and slaveholders in the Old Dominion. Active in the Virginia legislature and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, he was a moderate politician during the Revolution—often viewed as sympathetic to the British (but not quite a Loyalist). |

![[12] Esek Hopkins, master](../Images/Thumbnails/Item12_thumb.jpg) |

[12] Esek Hopkins, master larger view

Brown & Co. finally got someone to hire on as master of the Brig Sally. Hopkins was directed to trade for slaves to be sold in the West Indies for hard cash or bills, had the freedom to sell the cargo (and even the brig itself) at his discretion, and was asked to bring “four likely young slaves,” boys of fifteen years or younger, back to Providence for the family’s own use. This mezzotint engraving shows Esek Hopkins as the first commander of the nascent United States Navy, standing in front of two American ships of war with two flags, the Liberty Tree and the Navy Jack flag with the motto, “Don't tread upon me” and a snake upon a striped background. This was one of a series of prints made to supply the British public with (fictitious) portraits of American military leaders. |