| |

MAPPING SUGAR

Early modern maps of the sugar colonies signaled the importance of sugar in a number of ways—most of all in delineating the ever-increasing amount of land given over to plantations, forts, ports, and other infra-structure required for the cultivation, processing, transportation, and defense of the commodity. Left unmapped is what this huge agro-industrial complex destroyed—such as the forests (and the animals that lived within in them) in islands like Barbados. A striking exception to this is Hapcott's manuscript estate plan. These maps were all produced between the 1630s and '70s—a period of huge growth of the sugar industry in Barbados and the initial British conquest and development of Jamaica. Their makers all used cartographic conventions like icons and vignettes to enliven the pictorial effect, but represented the sugar economy in different ways. Like other printed images, maps were frequently reprinted and re-published, often without the permission of the original designer or publisher. Such printing practices remind us that questions of intellectual property, as well as real property, were involved in the culture of sugar.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Imaging Deforestation

John Hapcott, "This plott representeth the forme of three hundred acres of land part of a plantation called the Fort Plantation of which 300 acres Cap. Thos. Middleton of London hath purchased," watercolor. London, [ca. 1646].

This partial plan of Fort Plantation in Barbados is regularly dotted with trees, denoting the forests native to the island; it also strikingly represents the rapid process of deforestation by showing tree stumps in the upper register, designated "fallen land" (under preparation for sugarcane planting) and in lower green sections devoted to pasture and potatoes.

|

|

|

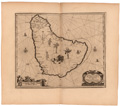

Barbados in Flux

"A topographicall description and admeasurement of the yland of Barbados in the West Indyaes with the mrs. names of the seuerall plantacons," engraving. In Richard Ligon, A True & exact history of the island of Barbadoes. London, 1673.

In this map the charming camels reference a doomed attempt to introduce them to transport hogsheads of sugar; the animals languished because no one knew how to care for them. The Indian marks a ghostly presence: most of the island's Caribs were killed, died of disease, or left after the Spanish invaded in 1492. The trees ornamenting the spaces on the map vanished quickly as land was planted in sugarcane: they were gone by the time this second edition of Ligon's book appeared. The hogs the Spanish introduced into the island fared better than the camels, trees, and Caribs: they multiplied successfully and were viewed as pests. They were hunted as runaway slaves were, and Ligon balances a scene of hog hunting (upper right) with slave hunting (upper left). This map raises the question of flux and change as it attempts to fix the island as an artful colonial space.

|

|

|

Mapping Connections and Difference

"Novissima et acuratissima Barbados descriptio," engraving. In John Ogilby, America: being an accurate description of the New World. London, [1671].

This outline map stresses Barbados' colonial connection to Britain by calling attention to hilly Scotland, the northern region of the island. This supposed topographical similarity is offset by the difference between colony and metropole suggested in the images that dot the rest of the map: the sugar mill with black slaves, tropical plants (pineapple, cabbage tree, papaw), and imported sugarcane. The web of lines overlaying the map recalls the rhumb lines of the Mediterranean portolan chart, which denote particular compass headings for navigational purposes. This "faux" portolan feature lends a note of maritime authenticity to Ogilby's land-focused presentation, and emphasizes the colony's connectedness to other sites in the Atlantic world. |

|

|

Conflict and Measurement

Joseph Moxon, "A new mapp of Jamaica. According to the last survey," engraving. London, 1677.

Moxon's flamboyant reworking of a map of Jamaica by John Man celebrates the island as a British conquest held by force. Military banners bristle in the center of a display framed by two canons. Animals and exotic plants serve as decorative space fillers for the un-surveyed areas. Moxon has represented ongoing conflict with a vignette of two men firing at each other—at either a great distance or very close, depending on how one reads their position within the triangular border of the unnamed parish that surrounds them. In the lower right, a black slave holds the map's scale in one hand and a bundle of sugarcane in the other. This vignette suggests that sugarcane and slaves are the true measures of this island. |

|

|

Commerce as Movement

Samuel Copen, "A Prospect of Bridge Town in Barbados," etching. London, 1695.

This birds-eye view from the water testifies to the high productivity of sugar plantations in Barbados by picturing the island’s only major harbor lined with warehouses and thronged with shipping. The ocean is shown churned up—not by a storm, given the fluffy clouds that ornament the view, but by the movement of ships. The agitated waves lend visual variety to a view lacking dramatic focus, and also suggest the pulsing activity of the sugar trade out of this port. |

|

|

Sugar as Energy and Currency

Richard Forde, "A New map of the island of Barbadoes wherein every parish, plantation, watermill, windmill & cattlemill, is described." [London, 1675-76].

This map is bristling with names and icons, suggesting the acceleration of agricultural development across Barbados at this time. Although the descriptive text under the smiling figures of Britannia and Plenty mentions that cotton, ginger, aloe, and other crops are grown on the island, the only commodity imaged on the map is sugar. It is depicted as icons denoting the energy source—wind, water, or cattle--used by mills to extract the juice from the cane. Ford got the Barbados assembly to pass an act prohibiting copying of the map—a strange gesture, since there were no copperplate presses on the island at this time. The penalty for printing the map without Ford’s license: 2000 pounds of sugar. |

|

|

Mapping Jewish Planters

Aleander de Lavaux, "Algemeene kaart van de colonie of provintie van Suriname," hand-colored engraving. Amsterdam, [ca.1758].

This brightly colored display map advertises Dutch colonialization in Suriname via the interlocking geometrical shapes of the sugar plantations that jut out from the rivers and spread into the green and yellow areas marking lands as yet undeveloped by Europeans. The conflict that comes with the establishment of plantation slavery is acknowledged by the bright red flames, which mark the location of a slave rebellion.

Half of Suriname’s European population was comprised of Portuguese Jews, who established plantations on the savannah. On the map their presence is denoted by the Jewish names mixed in with the Dutch on the plats and the lists of planters that frame the map, and by the words “de Joode Savanne” and “Joodish Dorp (village)” set in the yellow/green section of the map. This area was also occupied by communities of maroons (runaway slaves who formed their own settlements) and native peoples. |

|

|

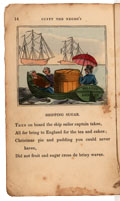

Sugar Crossing the Waves

"Shipping sugar," hand-colored wood engraving. In Cuffy the Negro's doggrel description of the progress of sugar. London, [1823].

While sugarcane, mills, and plantations commonly appear as fixed icons on maps of the West Indies, sugar is rarely pictured in motion over the ocean—a crucial part of its journey from cane field to market. This illustration from an anti-slavery children's book places a hogshead of sugar on a small boat heading out to a transport ship bound for London. |

|

| |

Exhibition may be seen in Reading Room from SEPTEMBER 2013 through december 2013.

K. Dian Kriz (Professor Emerita of History of Art and Architecture, Brown University), guest curator, with assistance from Susan Danforth (Curator of Maps and Prints); Elena Daniele (JCB Stuart Fellow 2012-13), curatorial assistant. |

|