Our approach regards perception and action as two sides of the same coin, expressing a currency which is not the veridical Euclidean representation of the environment. Studying perception is the first step to revealing how visual information is organized to spring action: Perception presents the action space. Our first mission is therefore to study the visual encoding of 3D object properties. The relationship between visual encoding and the unfolding of a motor action, which requires the same 3D properties, is the aim of our second line of research exploring the visuomotor mapping. We believe that perception and the motor mapping are always synergistically updated. Thus, our third mission is to study the plasticity of the motor mapping and visual encoding of 3D information.

How does vision inform the visual system about the three-dimensional structure of the world? What information is important, for a complex organism like human primates, to be able to successfully interact with the surrounding environment?

A large community of researchers, spanning psychophysicists, cognitive neuroscientists and neuroscientists assume that the goal of the visual system is to reconstruct the Euclidean structure of the world. All theoretical and empirical efforts are therefore placed in understanding how the brain achieves this goal. Surprisingly, the Euclidean representation assumption is never a topic for debate.

We argue that the Euclidean representation of objects is neither the goal of the visual system nor a feature of the perceptual space. Stripping away this hypothesis from the guiding principles of research in human 3D vision, we seek alternative computational models and empirical tests for understanding how the multitude of visual signals shapes our perceptual experience of the 3D world.

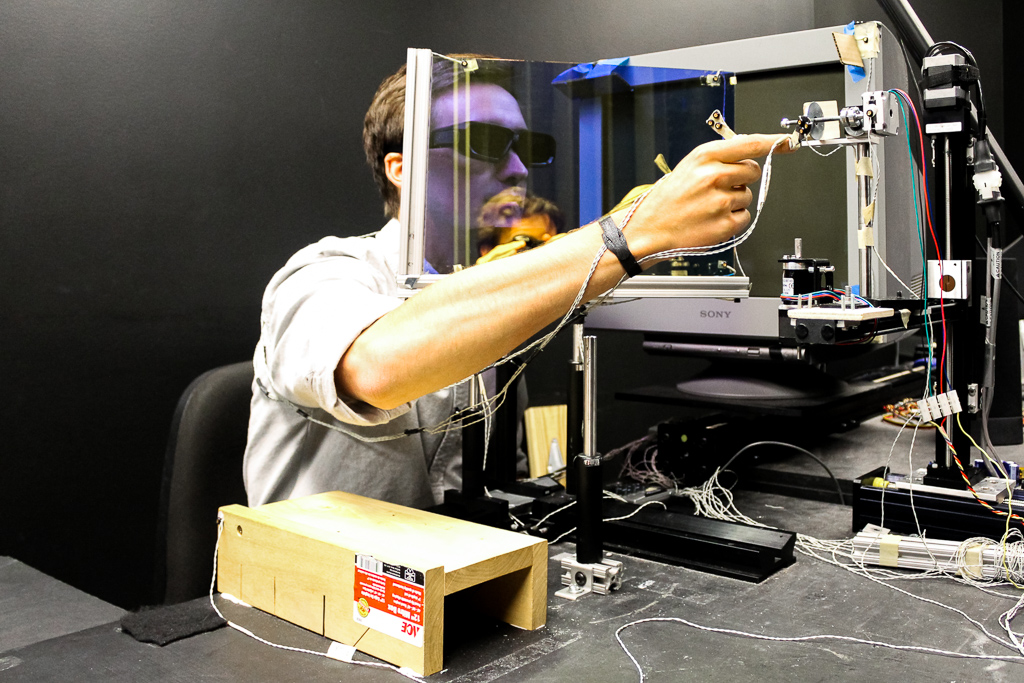

Evan grasping something in virtual reality.

— Domini, F., Caudek, C. (2013). Perception and Action Without Veridical Metric Reconstruction: An Affine Approach. In S J. Dickinson Z. Pizlo (Eds.). Shape Perception in Human and Computer Vision (pp. 285-298). Springer London.

— Domini F, Caudek C. Matching perceived depth from disparity and from velocity: Modeling and psychophysics. Acta psychologica. 2010; 133(1):81-9.

A graphic of our virtual reality setup.

If the visual system is unable to reconstruct the metric properties of the world, how can we grasp objects if we don't know their true size and location? Is it possible that perceptual distortions are only found in purely perceptual tasks, made by passive observers viewing the stimulus from a static point of view?

In order to address these questions, we built a complex VR environment where observers can interact with objects located within their personal space. Within this environment the observer's head can be tracked as well as the position of their upper limbs. Observers can make perceptual judgments about virtual objects, or we can study their behavior when they reach for or grasp these objects. In addition, they can also feel them, since we built a system of computer-controlled moving parts that can provide haptic feedback.

This sophisticated system allows us to pursue a new line of research where we study how depth information is used for grasping virtual objects. Instead of only asking perceptual judgments about the 3D structure of an object, we determine how the aperture between finger and thumb is related to the depth of the object at the end of a grasping action. In recently published studies, we provide converging evidence with what we found with visual tasks.

— Campagnoli C, Croom S, Domini F. Stereovision for action reflects our perceptual experience of distance and depth. Journal of vision. 2017; 17(9):21.

— Bozzacchi C, Domini F. Lack of depth constancy for grasping movements in both virtual and real environments. Journal of neurophysiology. 2015; 114(4):2242-8.

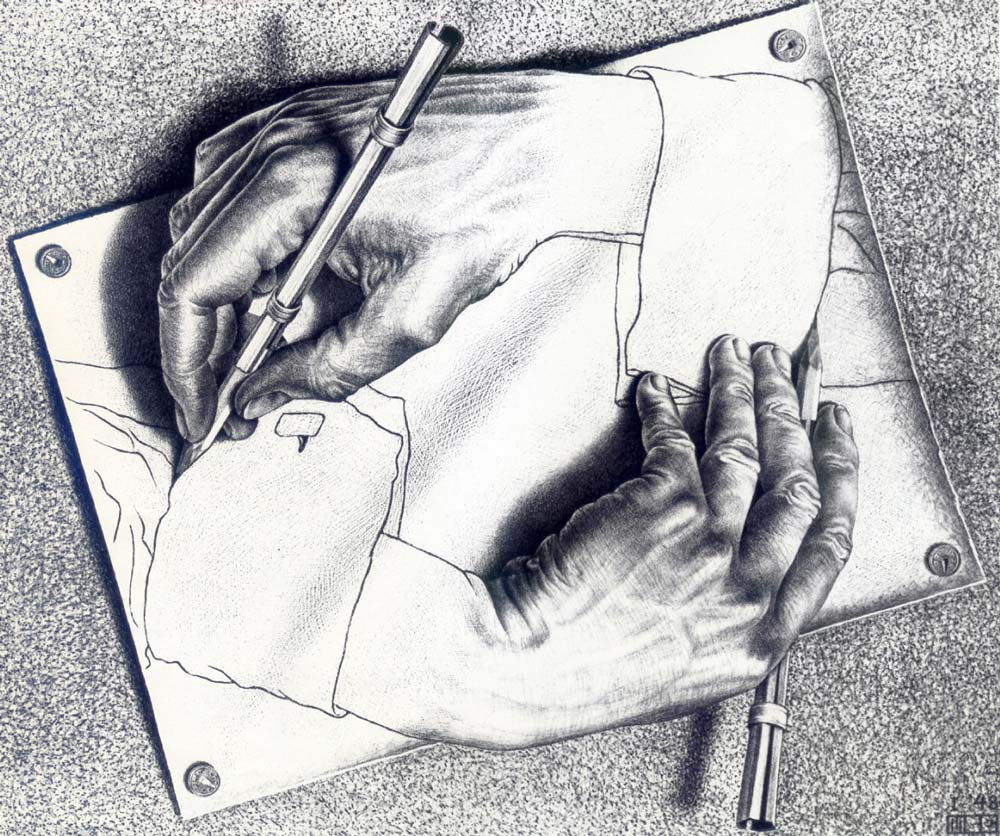

Perception and action have been traditionally considered as distinct brain functions. This view took hold following a number of paradoxical dissociations between perception and action in healthy and neurologically impaired individuals. We take a fundamentally different view, proposing that these processes work together to form a coordinated system, where perception informs action about the state of the world and, in turn, action signals perception when perception is faulty. We hypothesize that this system works cooperatively, leveraging error signals from sensory feedback when interacting with the environment to modify the state of the motor system when this is sufficient or to change the very perceptual interpretation itself. While error signals have been studied extensively in the sensorimotor adaptation field, advances made here have yet to be extended to develop an integrated framework for how perception and action coordinate adaptive behavior.

This approach brings together two fields, 3D visual perception and sensorimotor adaptation, to build a comprehensive framework with the potential to transform current understanding of visually guided action.

M.C. Escher's "Drawing Hands" © 2009 The M.C. Escher Company-Holland

— Cesanek E, Domini F. Error correction and spatial generalization in human grasp control. Neuropsychologia. 2017; 106:112-122.

— Cesanek E, Campagnoli C, Taylor JA, Domini F. Does visuomotor adaptation contribute to illusion-resistant grasping? Psychonomic bulletin & review. 2017

— Volcic R, Fantoni C, Caudek C, Assad JA, Domini F. Visuomotor adaptation changes stereoscopic depth perception and tactile discrimination. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013; 33(43):17081-8.