The Muculufa Master and Reconsiderations of Castelluccian Sequences

by Susan S. Lukesh

The archaeological site at La Muculufa (Butera) is 15 kilometers inland from the mouth of the Salso River. The peak of the eminence rises precipitously from the river, thus creating a visual reference point for the entire valley from Caltanissetta south to the gorge through which the Salso enters the plain of Licata. Archaeological research was carried out during the decade 1982-1991 by the Soprintendenza ai Beni Culturali ed Ambientali of Agrigento under the leadership of Professor Ernesto De Miro and Doctor Graziella Fiorentini and with the collaboration of Brown University, Providence R.I. (USA) (Holloway et al 1990, McConnell 1995). This work brought to light a good part of a village of the Early Bronze Age (Castelluccian Culture). Some 200 chamber tombs visible in the cliffs above the site were documented (Parker 1985). But the great success of the excavations was the exploration of a sanctuary frequented certainly by local people but also by others who were coming from elsewhere in the Salso Valley.

|

| Fig. 1. |

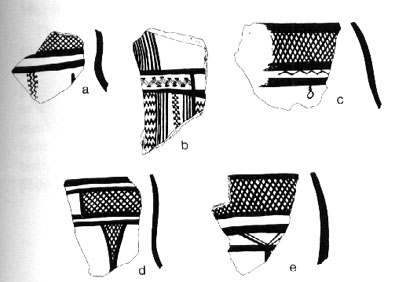

Following the ritual meals consumed on the spot, these people left behind a remarkable quantity of decorated pottery. In a number of cases there are sherds from vases identical in form and decoration from the area of Caltanissetta (Xiboli, Monte San Guiliano) now in the Regional Archaeological Museum, Caltanissetta(1). Still other fragments found in the sanctuary at La Muculufa find exact parallels in pottery at the sites of Canticaglione and Casalicchio-Agnone, both situated along the edges of the coastal plain surrounding Licata, sites included here in the region of the Salso Valley (Holloway et al 1990: 36-37, Lukesh 1995), Fig. 1(2).

Other evidence also confirms the presence at the sanctuary at La Muculufa of people from other sites in the valley. The corpus of motives found on the decorated pottery excavated at the La Muculufa, and organized in our computerized data bank, is extensive. Fully 100,000 sherds were registered during the campaigns of 1982-1986, 30,000 decorated and of those 22,500 from the sanctuary. In this material there are four decorative motives that are found exclusively in the sanctuary; that is to say, they do not appear in the material from the village. It is evident that the vessels decorated with these motives were brought to the sanctuary from other places around the valley because I have found three of these motives on pottery (the so-called dippers or cups) from the site of Canticaglione. If these vases had been made at La Muculufa together with other pottery produced at the site, vases with the same decoration should have been present in the village. However, if they were made at Caticaglione and then brought to La Muculufa on the occasion of religious festivals, the appearance of such decoration should be limited to the sanctuary area(3). And this is exactly what is proven by the archaeological evidence.

This is the evidence which has led to the identification of the sanctuary at La Muculufa as a federal sanctuary(4).

The excavations of La Muculufa have also been distinguished for the ample C14 dating of the site (Holloway et al 1990, McConnell 1995). There are dates from twenty-three samples, five from the village and eighteen from the sanctuary, and together they agree that the end of both came about 2100 B.C. (calibrated). And considering the unusually secure dating of this site, it may be opportune to make some comments on the terminology which has become current in studies of Castelluccian pottery. In introducing the term "Castelluccian Culture" during the 40's and 50's, Luigi Bernabù Brea hypothesized a line of descent from pottery known from the site of Sant' Ippolito (Caltigirone) to Castelluccian decorated wares (Bernabù Brea 1958: 82-84, 108). A key diagnostic element in pottery from the Sant' Ippolito site, which we must remember, had a lengthy development in prehistory but was never systematically investigated or published, is polychrome pottery with black bands on a red background bordered with white(5). The same decorated scheme is observed with decorated material from La Muculufa but it occurs on fragments from vases fashioned from the same clay that served to produce other wares, not so decorated, at the site (Moore 1995). For this reason the term "Sant' Ippolito style" neither can serve to postulate the origin of the vessels themselves at La Muculufa nor can it support a chronology; it must remain only a descriptive label(6).

The fine ware pottery from La Muculufa with the characteristic Castelluccian decoration in black on red or yellowish background has recently been defined as belonging to the "Naro Style" (Maniscalco 1995). The use of such a term derived from a group of vases collected many years ago from chamber tombs at Naro is very generic and means little more than "Vases with complex symmetrical decoration"(7). While the fine ware from La Muculufa has some parallels to material from Naro, these parallels have nothing of the precision that has been shown above in our search for parallels with material from the Salso Valley region such as that from Canticaglione. At La Muculufa, moreover, the study of pottery has gone well beyond the question of vases brought to a sanctuary from surrounding sites to the identification of a master vase painter and his work(8).

|

| Fig. 2 |

If we examine the masterpiece of the Muculufa Master (Fig. 2), an amphora with asymmetric handles, we find ourselves faced with a decorative pattern on the lower body which has much in common with other Castelluccian pieces but in one respect -- the thin vertical lines connecting the peaks of the chevron segments -- is absolutely unique (Lukesh 1993). A brief look at the remainder of the vessel shows that the neck is divided into metopes of various patterns, each delimited by another metope filled with a pair of angular lines. The handle zone on the neck is solid black. Each motif used is created from diagonally placed lines -- none horizontal or vertical, with the sole exception of the vertical lines joining the angular lines on the round body. If we look closely at the motif filling the left and right metopes on the neck, we see that this horizontal fishbone pattern was painted as if a series of rectangular spaces was filled with diagonal lines, alternating in direction, band by band. The effect is quite different from painting a series of parallel vertical zigzag lines and the execution much more easily controlled to create the dense fishbone pattern. The final impression could be achieved by both techniques but the ability to create such dense patterns is more remote if each vertical zigzag is drawn, one after the other.

|

| Fig. 3 |

Thus, in addition to the thoroughly original element (angular bands connected by vertical lines), the Muculufa Master show his personality and style in the way he chooses and combines motives from the general repertoire of Castelluccian ceramics as well as in the high quality of his work and sureness of hand. The name vase is unusual for the motif covering the lower body, for the well-balanced composition of carefully selected motives and for the quality of the execution itself. Nonetheless, of the over 20,000 painted fragments recovered from La Muculufa, there are a number which exhibit just such qualities even if, unfortunately, few can be reconstructed to a full pot shape.

The style of the Muculufa Master stands out even more clearly if we examine a workshop piece, executed by a painter under the influence of the master but clearly a follower. Fig. 3 illustrates a pot almost identical in shape to the name vase almost identical in shape to the name vase, an amphora. The composition is well laid out with alternating metopes of multiple angular lines and vertically positioned angular lines adorned with spiral rather than "berries". This second motif has three lines in the central panel or metope and only two on the left and right metopes. As on the name vase, the handle area is solid black. The neck and body are delimited by a set of three unadorned zigzag lines; the body if filled with the same multiple line pattern used in the neck metopes; and the handle area on the body carries the hatched band seen on many of the vases, including the name vase.

The execution of the motifs is less fine and the selection and organization of motifs less complex than on the name vase. In fact, the size of the metopes on the neck, which are filled with the same pattern on the lower body, changes the impression of the vessel to one primarily decorated with one motif, occasionally relieved by sets of zigzag lines; this is quite different from the design structure on the name vase. While this amphora was not executed by the Muculufa Master, it is likely that it was created with the knowledge of the name vase tradition and the "manufacturer's shop"; that is, the painter was familiar was familiar with the set of structural rules governing the design composition of the pots discussed above, as well as the individual selection of motives. It was, however, executed much more quickly and less expertly.

Let us give a further moment of attention to the problem of the relationship between the Castelluccian ceramics of La Muculufa and those of the so-called "Naro Style." The material from Naro, as well as that from the site of Partanna in the area of Selinus, again a site where material was collected in the past from chamber tombs, has undergone extensive treatment by Marco Pacci and Sebastiano Tusa (Tusa, Pacci 1990). But the interest devoted to such a collection of material has meant that in central-southern Sicily, and in the area of Agrigento in particular, the better decorated pottery has been brought together under the heading of AProtocastelluccian@, including the "Naro Style", the "Partanna Style", and even the fine wares form La Muculufa (Tusa, Pacci 1990; Maniscalco 1995:56). But what is left for standard Castelluccian? Almost nothing. According to Luigi Bernabù Brea, there are few sites in greater Agrigento belonging to Castelluccian, such as Caldare, Monte Sara, Monte d'Oro and Monteapert (Bernabù Brea 1976-77: 51-51). As far as the pottery is concerned, these are all poorly documented sites and the little pottery that is published from is hardly uniform in its decoration(9). Therefore, it may be legitimate to ask whether the time has not come to abandon the idea of a general "Protocastelluccian" in which all fine ware is early (Proto) and the rest is later (standard) and ask if we might not be better served by identifying and studying local sequences built up as Bernabù Brea build up the sequence for Aetna region? (Bernabù Brea 1968-69, Cultraro 1989).

Quite recently the excavation of Giuseppe Castellana at the remarkable site of Ciavolaro have thrown a ray of light on the problem of Castelluccian pottery in the region of Agrigento (Castellana 1996). At Ciavolaro, in a rich funerary context where over several centuries there predominates pottery of the Rodi-Tindari-Vallelunga style, there is also Castelluccian material. The last phase of Ciavolaro borders on the Middle Bronze Age, and in this context one finds a kind of Subcastelluccian, as it were the last breath of the long tradition of painted pottery in the Early Bronze Age. On the other hand, from the first two phases in the sequences at Ciavolaro there is pottery similar to that of the tombs of Naro but not especially similar to that of La Muculufa. There are no radiocarbon dates from Ciavolaro itself and the attempt to date the material from Ciavolaro and Naro to that from La Muculufa and hence describe a general Castelluccian sequence across south-central Sicily is premature at best.

At La Muculufa the development of pottery and pottery decoration is very different from that seen at Naro, Partanna, and Ciavolaro. The ALa Muculufa master(10) created his masterpieces before the end of the third millennium. His work may well represent a Protocastellucian phase but if so, it is not one represented at Ciavolaro, at least on the basis of the published material. Without radiocarbon dates from Ciavolaro itself, we can only hypothesize that Ciavolaro represents either a phase later than La Muculufa -- and so is perhaps standard Castelluccian -- or, if an earlier phase, is in fact part of its own local sequence which deserves detailed study and definition on its own.

Bernabù Brea, L.

1958 La Sicilia prima dei Greci.

1968-69 Considerazioni sull=eneolitico e sulla prima eta del bronzo della Sicilia e della Magni Grecia, Kokalos, XIV-XV, 1968-69: 42ff.

1976-77 Eolie, Sicilia e Malta nell eta del bronzo, Kokalos, XXII-XXIII, 1976-77: 40ff.

Castellana, G.

1996 La Stipe votiva del Ciavolaro nel quadro del Bronzo Antico Siciliano.

Cultraro, M.

1989 Il castellucciano etneo nel quadro dei rapporti tra sicilia, Penisola Italiana ed Egeo nei secc. XVI e XV a.c., Sileno, XV, 1989,1-2:259-86.

Holloway, R.R., M.S. Joukowsky, and S.S. Lukesh

1990 La Muculufa, The Early Bronze Age Sanctuary: the Early Bronze Age Village (Excavations of 1982 and 1983), Revue des archeologues et historiens d=art de Louvain, XXIII, 1990: 11-68.

Lukesh, S.S.

1993 The La Muculufa Master and Company: The Identification of A Workshop of Early Bronze Age Castelluccian Painters,Revue des archeologues et historiens d=art de Louvain, 2 (1993): 9-24

1995 Reflection on Castelluccian Material and Future Research Directions, in McConnell 1995: 187-210.

McConnell, B.E.

1995 La Muculufa II (Archaeologia Transatlantica XII) with complete bibliography to date.

Maniscalco, L.

1995 The Castelluccian Ceramics, in McConnell 1995: 37-66.

Moore, M.

1995 Petrographic Analysis of Castelluccian Ceramics, in McConnell 1995: 66-73

Mosso, A.

1907 Villaggi preistorici di Caldare e Cannatelo presso Girgenti in MontAnt., XVIII, 1907, col. 595 and pl. IV .

Orlandini, O.

1962 Il Villaggio Preistorico di Manfria, Presso Gela..

Orsi, P.

1895 Vasi siculi della provincia di Girgenti, BPI, XXI, 1895.

1897 L=eta della necropoli di Castelluccio in provincia di Siracusa, BPI, XXIII, 1897.

1907 Villaggio siculo a Caldare presso Girgenti, BPI, XXXIII, 1907.

1910 Due villaggi del primo periodo siculo, BPI, XXXVI, 1910.

Pacci, M.

1982 Lo stile Aprotocastellucciano@ di Naro, RSP, XXXVII, 1982:187-216.

Parker, G.

1985 The Early Bronze Age Chamber Tombs at La Muculufa, Revue des archeologues et historiens d=art de Louvain, XVIII, 1985: 9-33.

Tusa, S.

1992 La Sicilia nella preistoria, ed. 2.

Tusa, S. and M. Pacci

1990 La collezione dei vasi preistorici di Partanna eNaro..

endnotes

- The author is grateful to Dr. Graziella Fiorentini for permission to examine this material in the fall of 1986 before the creation of the independent Superintendency of Caltanissetta. The present paper was originally presented at the I Congresso Internazionale di Preistoria e Protostoria Siciliane, Corleone, 1997.

- The borders of the Salso Valley Region (and adjoining coast line region) are very well defined on the east. Caticaglione (situated just below Monte Desusino) belongs to the area centered on La Muculufa. Manfria, on the outskirts of Gela, does not. This latter site, before La Muculufa the most thoroughly investigated and published Castelluccian settlement, is rarely commented on in regard to its pottery (Orlandini 1962).

- Clear parallels to material from other sites in the Salso River Valley (Xiboli, Monte San Giuliano, and Cassalicchio-Agnone) and the neighboring Canicatti support this argument (Holloway et al 1990: 36).

- On the significance of the federal sanctuary see R. R. Holloway, The Classical Mediterranean, its Prehistoric Past and the Formation of Europe, http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Old World Archaeology and Art/publications/

- The site of Settefarine near Gela, usually cited as a companion to the Sant' Ippolito complex, is published summarily (Orsi 1910: 158).

- D. Amoroso, as summarized by Tusa 1992, has suggested that the Sant' Ippolito style is nothing more than a provincial manifestation of Castelluccian.

- For the "Naro Style", see Pacci 1982: 187-216 and Tusa, Pacci 1990.

- The word "his" is used in the generic sense. We can=t, of course, know if the artist was a man or a woman.

- The few pieces of pottery published from Caldare suggests long slender horned handles, simple cross-hatched designs in thick lines and heavy borders and black borders edged with white (Mosso 1907, Orsi 1907). From Monte Sara, on the other hand, the pottery (illustrated by Orsi 1895, pl. IV) can be compared with the vases from Naro and Partanna, while at Monte d'Oro (Orsi 1897, Pl. I-III), one finds a fine and precise style of a different character.

- The decorated material in Phase I (and Phase II) of Ciavolaro (as published) shows very little in common with La Muculufa decorated material and so it is not wise, in our opinion, to date Ciavolaro I by means of the C14 dates from La Muculufa as Castellan, cit.in note 27 does, on the assumption that the pottery at La Muculufa is a close relative of the groups from Naro and Partanna.