Alex Kuffner Providence Journal | USA TODAY NETWORK

BOB BREIDENBACH, THE PROVIDENCE JOURNAL

PROVIDENCE

In the past, the chances of human exposure would have been minimal, but climate change is dialing up the possibility of contamination. As extreme rain storms become more common, these low-lying streets around the Woonasquatucket are more vulnerable to flooding, which could release chemicals, volatile organic compounds or heavy metals like lead or cadmium from the ground or the river bottom.

In a study of the Providence metro area and five other urban centers around the country, Frickel and other environmental experts found thousands of previously-unknown relic industrial sites that lie within flood zones in close proximity to residents.

“The vast majority of manufacturing takes place in small mom-and-pop shops,” said Frickel, a professor at the Institute at Brown for Environment and Society. “They go out of business all the time. They move around a lot. Every time they move, we’re assuming they leave something behind. So the scale of potential contamination increases over time and over space.”

Because cities are always changing, these industrial spaces get reused and often forgotten, becoming a potential hidden danger to the people who live around them.

“The sites become invisible,” Frickel said. “They get lost.”

Most relic industrial sites are unknown to government agencies

Previous research has shown that some of the most polluted former industrial properties in the nation are at risk of climate-related weather disasters. In a 2019 study, the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that 60% of these so-called Superfund sites are in locations that are vulnerable to climaterelated events, including wildfires and flooding.

But the locations that are part of the federal Superfund program and targeted for cleanups represent only a small percentage of the places where pollution could have been left behind by past industrial activities.

Frickel and his co-authors — Thomas Marlow, a postdoctoral fellow at New York University and James R. Elliott, a Rice University sociologist — say the government drastically undercounts the properties that may still pose a hazard because many of the places are small, were used for industrial purposes generations ago before agencies started documenting contaminated lands, or have since been repurposed for housing, offices or parks.

“Ninety percent of historical industrial sites since the 1950s are not on agency radars,” Frickel said.

He’s written about the nation’s industrial legacy before. He and Elliott penned a book on the subject: “Sites Unseen: Uncovering Hidden Hazards in American Cities.” The new paper for the first time analyzes flood risk for these industrial sites.

Flooding may not have been a serious threat when the properties were initially developed many decades ago, but global warming has changed the equation.

Rain in the Northeast is increasingly falling in big events, rather than more gradually, in part because warmer air holds more moisture. Recent examples of heavy deluges in Rhode Island include the rains swept in by the remnants of Hurricane Ida in September 2021 and last month’s Labor Day storm that shut down Interstate 95 in Providence.

Lower-income, communities of color disproportionately at risk

By and large, the study found, the people most at risk from industrial pollution are lower income or from racial and ethnic minorities — groups Frickel describes as “socially marginalized.”

They live in neighborhoods like Olneyville, which the study found has one of the highest concentrations of former industrial properties in the Providence area. About 70% of the neighborhood’s residents are Hispanic and 15 percent are Black. The median household income there is about three-fifths the Rhode Island average.

The other part of Providence with a high number of relic sites is the former Jewelry District, which has been redeveloped into a hub of medical offices, research labs and high-end loft apartments.

But the risk isn’t just confined to the heart of Providence. Frickel has tracked industrial development in Rhode Island over time, starting with the 1950s when businesses were bunched in the urban core, many along waterways because their predecessors needed easy access to power and transportation.

Over time, however, they moved from Providence, Pawtucket and Central Falls and into the suburbs, following construction of I-95 as transportation by truck became more important. And instead of locating in dense clusters, industrial businesses became more spread out.

“Once that highway was built, you see the geography of industry change,” Frickel said.

Sites identified through old industrial directories

Frickel and the other researchers combed through old state business directories collected in public libraries to map the relic sites.

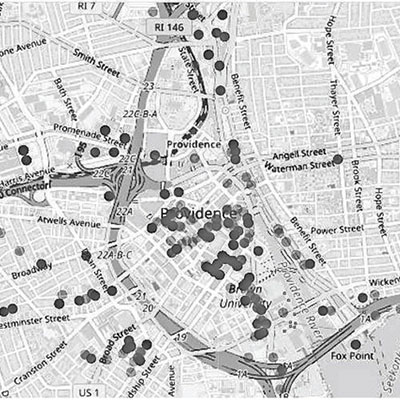

They took digital photographs of every page of every directory they could find going back 60 years and created an algorithm to search for businesses that used chemicals, manufactured plastics, refined fossil fuels, made concrete, fabricated metals or engaged in other industrial activities. They mapped the locations and cross-referenced them with flood risk projections by the First Street Foundation, a nonprofit that calculates climate risks. Then they combined it all with Census data to find out who’s living around these sites now.

They did this in six cities in different parts of the country. Along with Providence, they looked at Houston, Minneapolis, New Orleans, Philadelphia and Portland, Oregon.

They found more than 6,000 former industrial sites in the cities at a high risk of flooding by 2050. They estimate that 200,000 people live on the same block as at least one of these properties. In all six cities, they found the main predictor of a neighborhood having a flood-prone former industrial site is the proportion of non-white and non-English-speaking residents.

“All of them showed significant numbers of these old sites in low-lying, flood-prone areas,” Frickel said of the study area. “And in all cities, marginalized groups will be disproportionately impacted by this new kind of risk that’s emerging.”

Houston has the highest number of bygone industrial properties at risk of flooding, with 1,985, and the most residents nearby, with 78,000. But the Providence area, despite its much smaller size, is similar in terms of the number of relic sites that could flood. It has 1,882 and 28,000 people that live in their vicinity.

That in part stems from Rhode Island’s legacy of textile mills.

“And jewelry is a huge, huge piece for Providence specifically,” Frickel said.

Fears of pollution after 2010 floods

Five years ago, the extreme rainfall from Hurricane Harvey damaged Superfund sites in Houston, including one on the San Jacinto River, where a structure containing dioxins and other hazardous substances was eroded, according to the Government Accountability Office.

Nothing like that has ever happened in Rhode Island, according to the state Department of Environmental Management. But during the historic floods in March 2010, the Centredale Manor Superfund site on the banks of the Woonasquatucket River in North Providence flooded.

“Fortunately, the two onsite caps held up with minimal washout and a visual inspection showed that no additional contaminated materials washed into the river,” DEM spokesman Michael Healey said. “The site also has a large volume of contaminated sediment in the river that we feared could be mobilized and spread downstream.”

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency sampled the river and found that none of the sediment spread beyond the existing contaminated area, Healey said.

Since the 2010 floods, the DEM’s Office of Land Revitalization and Sustainable Materials Management, which oversees contaminated sites, factors climate change impacts into any remediation plans.

“Those events put the issue front and center for us,” Healey said. “Typically, sites we oversee are capped and armored to the flood plain, so flood impacts on the encapsulated waste are not expected.”

Alicia Lehrer, executive director of the Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council, said she worries about floodborne contamination at public recreation areas near the river, like Merino Park and Riverside Park. The EPA tested those sites after the floods in 2010 and found some dioxins at Merino Park but not in the playing fields.

“The area where contamination was found is fenced off now,” she said.

Frickel is careful to say that the places the study found are potential sites of contamination. They haven’t assessed each individual place for pollutants and whether floodwaters would release contamination.

“The problem is, we just don’t know,” he said.

He’s working with the DEM and the state Department of Health to better understand the particulars of individual sites.

“The work that Dr. Frickel has done is an important part of our understanding of the legacy of industrial activity in Rhode Island and informing our strategies for restoration and clean-up,” DEM director Terrence Gray said. “Climate change and the expectation of future flooding events threaten to affect disadvantaged communities. Historical industrial pollution in many of these same communities makes cleaning up these sites, and addressing social inequities, all the more urgent.”

Flood risk adds urgency to clean-up efforts

Frickel has seen the impacts of flooding up close. He and his family were living in New Orleans when Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005. Their house didn’t flood, but it sustained wind damage.

A quarter-of-a-million people fled the crippled city in the storm’s wake. They included Frickel, his wife and their daughter.

“It was a life-changing event,” he said.

The threat of hurricanes has always been apparent. But now flooding is coming in other ways, from higher tides exacerbated by rising seas, and, increasingly, intense rainstorms.

Frickel and his colleagues say these changes add urgency to the need to clean up properties used in the past for industrial purposes. They emphasize the importance of adding more protection around hazardous sites so they can withstand impacts of the weather.

The bottom line, they argue, is that flooding risk needs to be part of the conversation.

“The time is now to start dealing with this, because the flood risk is only going to go up and up and up,” Frickel said.

Frickel and the other researchers created an algorithm to search for businesses that used chemicals, manufactured plastics, refined fossil fuels, made concrete, fabricated metals or engaged in other industrial activities (See image at top right)