Notes Toward a Lost Correspondence

In advance of President Obama’s historic visit to Havana last year, Cuba and the United States agreed to restore direct postal service. This was not the highest profile milestone in the two countries’ journey toward “normal” relations. But in a symbolic enactment of “people-to-people” contact, Barack Obama himself sent the inaugural dispatch—a pleasant response to a seventy-six-year-old Cuban woman who had previously, via third-country mail, written the U.S. President and invited him to coffee.1

As with many so-called “firsts” of normalization, the President’s letter overshadowed similar occurrences that had transpired before. As an unexpected byproduct of my research into the history of the Cuban Revolution and the Cuban-American community, I had become aware that an important, if precarious, correspondence had been flowing between Cuban and U.S.—and particularly Miami—shores all along. Mail service during the decades following the Revolution’s triumph in 1959 may not generally have been direct, or efficient. Half of the letters sent in either direction may never have arrived. But certainly for the 1960s, and especially for the period before Cuba’s “divorce” from the United States was final, I found considerable evidence that mail and packages of varying types, and with varying kinds of contents, and yes, sometimes via direct transfer, did travel back and forth.

The discovery of these materials struck me as revelatory. After all, such communications were once deemed politically fraught. In an infamous 1972 speech delivered on the eleventh anniversary of the founding of Cuba’s Ministry of Interior, Raúl Castro highlighted contact with apátridas—literally “those without a country”— as one of the “subtle weapons” of “ideological diversionism” employed by U.S. imperialism.2 Yet Castro’s references to letters from Miami, supposedly filled with counterrevolutionary jokes, news clippings, and photos of foreign luxuries, also testified to the fact that some form of correspondence continued to arrive.

Indeed, when one scratches the surface of revolutionary-era cultural production, references to fugitive mailings begin to appear. In a minor scene of the legendary 1968 film Memorias del Subdesarrollo, Sergio, a well-to-do recluse who has decided to stay in Cuba, returns home to his apartment to find an envelope in his mailbox from his mother in Miami. “Every time the old lady writes me, it’s the same,” he says, annoyed that the letter has come accompanied by a stick of Juicy Fruit gum and a Gillette razor. “She knows that I don’t chew gum and I use an electric razor. The only thing I ask is that she sends me books and magazines, but nothing.”

More recently, contemporary writers have explored the non-material, less transactional meanings of mailings that crossed geopolitical lines. In a recent essay, Cuban-American writer Caridad Moro-Monlier recalled the “beautiful letters that arrived in airmail envelopes bordered in red and blue chevrons” from her mother’s first cousin in Cuba throughout her Miami childhood in the 1970s.3 Ana Dopico similarly has recounted how, growing up in Cuban Miami, letters to and from her aunt, grandmother, and cousins on the island provided “urgent epistolary intimacy to bridge the gap.” They represented a declaration of familial faith, she writes, in parallel to the forms of “political love” that otherwise placed relatives in opposing ideological camps and geographic sites.4 In fact, both writers note that part of the ritual epistolary exercise involved avoiding sensitive political commentary that might threaten the emotional connection, or be seen by the wrong eyes.

Together, these musings, President Obama’s letter, and my own scattered source base led me to ask: what would it look like to write a history of the “lost correspondence” between revolutionary Cuba and the United States — and between Cuba and the Cuban exile community specifically? What might the contents of such letters, or the fact and path of their material circulation, reveal about the complexity of life under the Cuban Revolution or in the post-1959 Cuban Diaspora? And finally, what might it mean to reimagine the history of U.S.-Cuban relations, less through the prism of government-to-government conflict, or via tropes of political fixity and miscommunication, than by tracing the everyday movement of mailings across a “sugar curtain” that purportedly divided Cubans in half?

This reflection represents a first attempt to answer these questions. It shares some initial observations from what I hope will become an article-length study. Here, I specifically explore one case in which correspondence was not just personal, but deeply political. Particularly in the 1960s, Cuban exile militants counted on the mail to gather salient news from allies back home. But they also engaged in furtive contacts with enemies that bridged and reinscribed the island’s political fissures.

***

Founded in 1960, the Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil en el Exilio (DRE, Revolutionary Student Directorate in Exile) was a major Cuban exile political organization made up of former anti-Communist participants in the student movement against Cuban dictator, Fulgencio Batista. Unlike their fidelista colleagues, members of the exiled DRE had become disaffected by the Revolution’s turn to the left. In Miami, they would receive funding from the CIA to foment civil unrest and armed resistance on the island. The Cuban government knew who they were. Many of their most well-known Havana-based counterparts ended up in jail.

So it may come as a surprise to find that such a “covert” organization’s records are full of regular-looking letters to and from points on the island — including some from prison. Some messages convey compromising operational contents. Others seem to be mostly personal communiques, often unsigned. A series of letters from one “Gregorio” in 1964, for instance, offered detailed accounts of growing lines to get food as well as the scarcity of staples like sugar.5 For DRE planners dreaming of invading the island, an accurate sense of Cuban social conditions was, in theory, a key to future success.

What is hard to ascertain is not just whether such reports could be trusted, but how they traveled in the first place. Complaints about how long letters took to arrive, combined with envelopes and postage preserved in the files, suggest that direct mail continued to flow through the mid-1960s. Yet plenty of references to indirect means of communication hint that letter writers also felt compelled to use more convoluted routes of exchange. “For weeks,” noted one anonymous correspondent in 1963, “I’ve been after my nieces to let me know when someone who could carry a letter is heading out.”6 This suggests that Cubans still departing the island often doubled as mailmen. And no wonder. A separate 1963 dispatch communicated the rumor that letters coming from or going abroad “were being personally checked by Minister of Communications Faure Chomón and a group of collaborators—informers, that is—in the upstairs of the Maxim Cabaret, located on the corner of 3rd and 10th, Vedado.”7

But aside from having to negotiate the possibility — fictional, real, or exaggerated — that correspondence would fall into unintended hands, mail between exiles and the island proved a minefield in another way. The DRE files suggest that opposing sides of Cuba’s Cold War attempted to use the mail proactively for intelligence gathering.

Notable in this respect is a series of letters from 1965 written ostensibly by Latin American students (and one gringo) at the University of Miami. In formal messages to institutions like the University of Havana’s Distance Learning Program (Comisión de Extensión Universitaria, who knew?), the Universidad Central de las Villas, and Bohemia and Mella magazines, young men with non-Cuban-sounding names like Carlos Marchelli and James Donald, Jr. wrote to request publications about the Cuban Revolution that they claimed they could not otherwise procure in Miami’s toxic anti-Castro environment. “I’m a student of political science at the University of Miami,” began one letter to the University of Havana, “and here they’re teaching opinions against the revolutionary process Cuba is living.”8 The message might seem genuine, the scenario plausible. But the archive in which the letter is preserved gives away that DRE members fabricated these messages to secure information that might prove useful for their anti-Castro efforts. Even more amazing, the receiving institutions on the Cuban side almost always replied.

The DRE’s own inbox suggests that they may have been the targets for similar tactics in the other direction. Indeed, while the organization received clandestine communications from cells on the island that appear authentic — and even used invisible ink — some of these mailings are anonymous and uncertain in origin. In one message dated March 20, 1963, a letter writer identified only as “your friend” informed members of the DRE in Miami of five potential collaborators in Havana that “appear to be revolutionary” but in reality were “the opposite.” The author listed their full names and addresses and concluded by describing his hopes for a future invasion. “Only blacks and bad lower-class people matter here,” he further complained.9 Was this a genuine, if disturbing, offer of assistance from a grassroots opposition sympathizer? Or was this a government trap to ferret out the DRE’s own affiliates on the island, by appealing to their presumed racism and enticing them to establish contact with the individuals named?

The answers elude us. But, either way, we would do well to take these exchanges as more than a real-life enactment of the comic Spy vs. Spy — whose creator, incidentally, was Cuban. Fugitive correspondence between revolutionary Cuba and anti-revolutionary Miami provides a window into the day-to-day rhythms of a polarized conflict. But letters also reveal that such polarization drew upon sly communications between Cubans who had managed to leave the island and those who, by choice or by chance, had stayed behind.

***

Is it possible to write a history of the “lost correspondence” between revolutionary Cuba and the United States? Can such an exercise serve as a valuable complement, or counterpart, to histories of human mobility and immobility otherwise characterizing Cuba’s particular experience of “Cold” War?

To be honest, I am still not sure. Nonetheless, I am drawn to such communications because I see what they can reveal. In contrast to the image of a nation totally cut off from the United States, they illuminate points of contact. And contrary to the simplistic idea of a nation, Cuba, severed in two by migration, they expose networks of political community and intrigue in transnational motion. Despite the real challenges of communication and a generally unidirectional physical exodus, Cuba’s “lost correspondence” casts the Florida Straits as a borderland of cautious exchange. But more than anything, these letters bear witness to their writers’ troubled (and at times troubling) imaginations. More ingrained ways of seeing the history of U.S.-Cuban relations, those that favor diplomatic cables over traveling envelopes, block us from seeing the true fluidity of the field.

* I am grateful to Carlos Velazco Fernández and Ricardo Pelegrín Taboada for their help with research for this piece.

1. Mimi Whitfield, “Barack Obama’s Pen Pal Hopes He’ll Stop by for Coffee,” Miami Herald, March 19, 2016, http://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/cuba/article....

2. Raúl Castro, “El diversionismo ideológico: Arma sutil que esgrimen los enemigos contra la Revolución,” Verde olivo, June 6, 1972, 15.

3. Caridad Moro-Monlier, “Un-slanting My Truth,” Bridges to/from Cuba (blog), May 13, 2016, http://bridgestocuba.com/2016/05/un-slanting-my-truth/

4. Ana Dopico, “Cuban Pictures and Political Love,” Cuba Cargo Cult (blog), March 19, 2016, https://cubacargocult.blog/2016/03/19/cuban-pictures-and-political-love/

5. For example: “Gregorio” to “Queridos Amigos,” December 2, 1964, Box 23, Folder 326, Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil en el Exilio Records (DRE), Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, FL.

6. Anonymous to “Mi querido tío del DRE in Xto,” March 12, 1963, Box 23, Folder 325, DRE.

7. “C.R.E.R.C.” to “Los Compatriotas del Directorio,” January 2, 1963, Box 23, Folder 85, DRE.

8. Alfonso Martínez Olive to “Sr. Director de la Revista Vida Universitaria,” March 18, 1965, Box 23, Folder 326, DRE.

9. “Su Amigo” to “Mis Valientes Amigos,” March 20, 1963, Box 23, Folder 85, DRE.

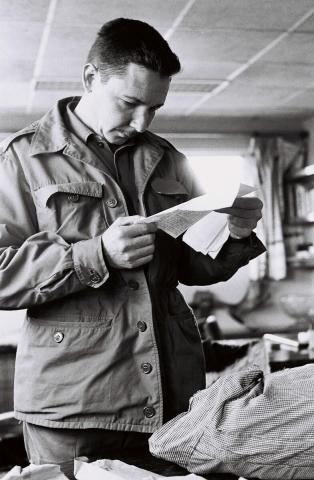

Image: “Raúl Castro with mail bags,” 1964, Deena Stryker photographs, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.