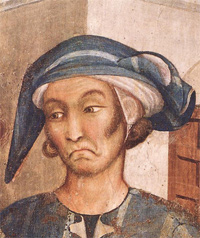

Jesters

The protagonist of Day 2, novella 1 is Martellino. He and his friends Stecchi and Marchese are introduced as jesters:

"These three used to do the rounds of the various courts, where they would entertain their audiences by putting on disguises and making all manner of gestures, by means of which they could impersonate anyone they pleased."

They are traveling jesters, familiar figures in the courts and the marketplace. It is their profession to entertain people.

There were, in the Middle Ages, two different types of jesters, morally subnormal (under the norm) but not mentally deranged individuals whose acknowledged, socially "deviant" behavior is acceptable as a source of entertainment: a) buffoons who used bodily excesses (e.g. gluttony), gossips, and tricks to entertain audiences in the marketplace and during popular festivities, and b) court-jesters who entertained at court.

Both the buffoon and the court jester (sometimes the same individual) generally relied upon his perceived mental deficiencies or physical deformities to entertain his hosts. Such characteristics, however, often deprived him of individual rights and civic responsibilities and put him in a paradoxical position: he was at once representative of outlaws and outcasts and dependent upon the support of his social group (or audience).

In the Middle Ages there was a widespread belief that good-humored joking protected a person from misfortune. Therefore, the jesters were considered naturally "lucky" and as such could transfer their good fortune to their noble patrons. Indeed, the court prince (or king) often charged the jesters with the task of continually provoking his courtiers in order to deflect pent-up frustration or wrath away from himself and the other noblemen and ladies. They became a sort of scapegoat or living mascot who could, through pranks and witty banter, bring good luck to his master and likewise "absorb" social friction. It is because of this special social function that court jesters were generally exempted from censorship and were allowed to behave in ways which would have been unacceptable for other members of the court.

(B. C) Welsford, Enid. The Fool, his Social and Literary History London: Faber & Faber,1968.