![]()

Detoxification

Detoxification is a precursor to treatment for people who have been identified as dependent on a substance. Medically supervised detoxification is often needed to counteract withdrawal complications before treatment can begin. However, it is recommended that the justice system not routinely mandate an individual into detoxification without medical advice because it may not be medically necessary or recommended. For example, detoxification could be medically contraindicated by HIV or pregnancy. Additionally, forced, unmedicated, unsupervised detoxification could cause resistance to future treatment and in some cases death.

Most often detoxification occurs in a hospital or facility where medical care is readily available, but it can also be successful in an ambulatory setting. The manifestations of withdrawal can range from mild dysphoria to life-threatening convulsions. There are two common methods to alleviate the potentially dangerous effects of withdrawal: (1) the dose of the abused substance is slowly tapered or (2) a long-acting pharmaceutical medication similar to the drug is administered. The process typically requires 3-5 days; however, the length of time varies depending on the individual, the type of substance used, and the severity of the problem.

While detoxification does treat the acute physiological effects of decreasing or eliminating substance abuse, it does not address the psychological, social, and behavioral problems associated with addiction. As a result, detoxification does not typically produce lasting behavioral changes necessary for sustained recovery.

> For more information on Detoxification:

TIP 45 Detoxification and Substance Abuse Treatment

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=hstat5.chapter.85279

American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry

www.aaap.org

American Society of Addiction Medicine

www.asam.org

Treatment

SETTING

Treatment services can be provided across a variety of settings/levels. There are four primary settings—or locations—where treatment usually take place:

(1) Inpatient, (2) Residential, (3) Intermediate, and (4) Outpatient. These settings correspond to “levels of care.” The level of care should correspond to the severity of an individual’s substance problem and not a criminal charge, conviction, or ruling (see page 36).

MODALITIES

“Treatment modality” refers to the specific activities used to relieve symptoms or induce behavior change. There are a variety of treatment modalities used to treat alcohol and other drug abuse; however, all generally fit into one of two categories: (1) behavioral and (2) pharmacological.

Behavioral Treatment

Because of the significant behavioral changes resulting from substance use disorders, behavioral therapies that help patients: (1) identify and avoid cues, (2) control urges, and (3) build healthy social supports. Behavioral therapy, also referred to as “talk therapy,” engages people in treatment, modifying their attitudes and behaviors related to alcohol and other drug problems and increasing their life skills to handle stressful circumstances and environmental cues that may trigger intense craving for substances resulting in relapse. Moreover, behavioral therapies can enhance the effectiveness of medications and help individuals remain in treatment and maintain their sobriety longer.

Pharmacological Treatment

Understanding that prolonged use of alcohol and other drugs can change the structure and function of the brain helps explain why pharmacological treatment can have an important role in the treatment of substance use disorders.

Historically, controversy has surrounded the use of pharmacological treatment for alcohol and drug dependence. The primary principles of pharmacological treatment are to decrease craving, allow individuals to stop using and remain substance free. Philosophically, some people have objected to the use of any medication to treat a substance problem. Society seems to have accepted that there are a number of pharmaceutical treatments for nicotine dependence—nicotine gum to help people stop smoking cigarettes—but there is less acceptance of using medications for alcoholism and drug addiction. Research supports the use of pharmacotherapy when accompanied with behavioral therapy for treating alcohol and other drug problems.

The Institute of Medicine (1990) defines the levels of treatment as:

Inpatient —“The provision of treatment for alcohol and other drug problems, including medical services, nursing services, counseling, supportive services, housing, laundry, and housekeeping for persons who require 24-hour supervision in a hospital or other suitably equipped and licensed medical setting.”

Residential —“The provision of treatment, including medical services, nursing services, counseling, supportive services, housing, laundry, and housekeeping for persons who require 24-hour supervision in a freestanding residential facility or other suitably equipped and licensed specialty setting.”

Intermediate — “The provision of treatment for alcohol and other drug problems, including medical services, nursing services, counseling, supportive services, housing, laundry, and housekeeping for those who require care or support or both, in partial (less than 24-hour) treatment or recovery setting. Those individuals generally need more intensive care, treatment, and support than are available through outpatient settings or they benefit from supportive social arrangements during the day in a suitably equipped and licensed specialty setting.”

Outpatient — “The provision of treatment for alcohol and other drug problems, including medical services, nursing services, counseling, and supportive services for persons who can benefit from treatment available through ambulatory care settings while maintaining their usual living arrangements.”

Research shows that when pharmacotherapy is used, many experience a decrease in craving, improved treatment outcomes, increased participation in 12-step programs, and a reduction in recidivism.

Medications can be provided in tablets, drinkable liquids or through injection. While pharmacological therapy can be useful, it should not be considered the sole answer to solving all alcohol and drug problems. Research does support the use of medications as a part of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes behavioral therapy as well as ancillary services to address the individual’s medical, psychological, social, vocational, and legal needs.

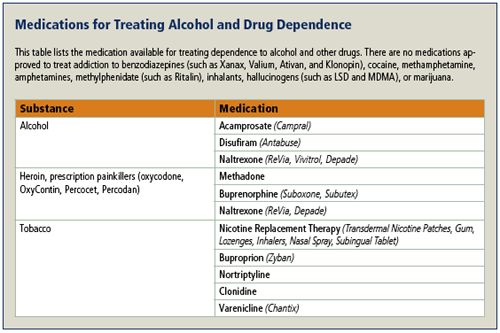

While there are no pharmacological treatments for stimulants, hallucinogens, or marijuana, medications for alcohol and opioid addiction are effective. Medications for alcohol addiction include Acamprosate and Disulfirum. Medications for opioid addiction include Methadone and Buprenorphine. Some medications, like Naltrexone, are used for both alcohol and opioid dependence treatment. The two prominent pharmacological properties of medications used to treat dependence are: (1) activating receptors and (2) blocking receptors in the brain. Medications that activate receptors, like Methadone, are called agonists. Medications that block receptors, like Naltrexone, are called antagonists. Both properties inhibit the euphoric effects of alcohol and other drugs, which provides individuals with substance use disorders the ability to make decisions and increases their likelihood of remaining in treatment, and maintaining sobriety.

STAGES OF TREATMENT Examples of Behavioral Therapies

|

Acamprosate (Campral) After alcohol use has ceased, an unpleasant physical condition, know as protracted abstinence syndrome, can develop. Acamprosate works to reduce the discomfort of protracted abstinence syndrome, increasing the likelihood that individuals will remain abstinent and sustain their recovery longer because they no longer feel the urge to drink alcohol to relieve their discomfort. Acamprosate is an effective treatment among motivated and abstinent populations. Research has found Acamprosate reduced the quantity and frequency of drinking and increased abstinent days, particularly among motivated patients. Among these patients, Acamprosate use resulted in a much higher percentage of abstinent days (72.5%) than the control group (58.1%) (Mason et al., 2006).

Disulfiram (Antabuse), approved by the FDA for the treatment of alcohol addiction in 1949, has been used primarily by patients who are not currently drinking in order to avoid using alcohol in high-risk situations. This medication discourages drinking by producing unpleasant physical effects, such as vomiting, chest pain, blurred vision, mental confusion, breathing difficulty, red face, and anxiety when even small amounts of alcohol are consumed. Research has demonstrated that Disulfiram can reduce drinking quantity and frequency (Garbutt et al., 1999).

| For more information on extended-release injectable Naltexone: Substance Abuse Treatment Advisory: Naltrexone for Extended-Release Injectable Suspension for Treatment of Alcohol Dependence |

Naltrexone (Revia, Vivitrol, Depade) is a synthetic opiate antagonist with few side effects. It is FDA-approved for treatment of alcohol and heroin addiction. Naltrexone has no potential for abuse or addiction. Daily treatment with Naltrexone, in combination with psychosocial support, leads to reduced alcohol craving and alcohol consumption, resulting in an approximately 50% lower incidence of relapse (Volpicelli et al., 1992). Adherence to daily naltrexone administration, like Disulfiram, is a common problem. However, a long-acting (30 days), injectable form of Naltrexone, known as Depot Naltrexone was recently approved by the FDA and is expected to improve treatment compliance and, in turn, improve treatment outcomes. Depot Naltrexone combined with motivational enhancement therapy has been shown to increase the likelihood of abstinence longer when compared to patients receiving only motivational enhancement therapy (Kranzler et al., 2004).

Methadone, a synthetic opioid, is used widely in Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) programs. In these programs, Methadone is administered in gradually increasing doses until a stabilizing dose is reached. At stabilizing levels, methadone markedly blunts the effects of heroin and prescription opioids. MMT can be a long-term treatment for opioid dependence. MMT is not a cure for opioid addiction, but it improves treatment retention and as a result decreases relapse and the health and criminal problems associated with illicit opioid use. (Rich et al., 2005).

Methadone, a synthetic opioid, is used widely in Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) programs. In these programs, Methadone is administered in gradually increasing doses until a stabilizing dose is reached. At stabilizing levels, methadone markedly blunts the effects of heroin and prescription opioids. MMT can be a long-term treatment for opioid dependence. MMT is not a cure for opioid addiction, but it improves treatment retention and as a result decreases relapse and the health and criminal problems associated with illicit opioid use. (Rich et al., 2005).

Medications for Opioid Addiction

| Addressing Nicotine Dependence Nicotine dependence is the most common substance use disorder in the United States, but often overlooked because it is not associated with legal problems and does not have an immediate societal impact. However, nicotine dependence is associated with enormous morbidity and mortality and effective pharmacologic and behavioral therapies exist. In addition, individuals with alcohol or other substance use disorders are much more likely to have nicotine dependence compared to those without substance use disorders. In one study of individuals who had received treatment for alcohol-dependence, nicotine-related ailments were the primary cause of mortality in 10-year period following treatment. For this reason, it is important to screen for nicotine dependence, encourage smoking cessation and offer smoking cessation treatment. |

Methadone is one of the most monitored and highly regulated medical treatments in the United States. The 1997 National Institute of Health Consensus Development Conference on Effective Medical Treatment of Heroin Addiction concluded that heroin addiction is a medical disorder that can be effectively treated in methadone maintenance treatment programs and recommended expanding access to Methadone treatment by increasing funding and minimizing federal and state regulations (Hall and Brown, 1997).

In 2005, 1,069 treatment facilities had an Opioid Treatment Program certified by SAMHSA to provide treatment with methadone. While the number of clients receiving Methadone fluctuates, the 2005 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services reported that on March 31, 2005 there were 235,836 individuals on Methadone in outpatient and inpatient treatment facilities (SAMSHA, 2006).

MMT is an effective, evidence-based approach to treatment for individuals in the criminal justice system particularly when combined with counseling. The Key Extended Entry Program (KEEP) at New York City’s jail facilities at Rikers Island was the first MMT program in the United States for incarcerated individuals dependent on heroin. Individuals enrolled in KEEP received a stable dose of Methadone in jail and were referred to community MMT programs. The KEEP program increased enrollment and retention in treatment after release from Rikers. Results from the first evaluation of the program found 85% of KEEP participants enrolled in treatment after release compared to 37% of the controls, who were rapidly detoxified from heroin using Methadone. At a 6-month follow-up, 27% of KEEP participants remained in treatment compared to 9% of the controls. Participation in treatment at follow-up was associated with decreased heroin use and decreased crime (Magura et al., 1993).

MMT use in prisons and re-entry programs is still limited. In 2003 most state and federal prison medical directors surveyed did not provide Methadone to opioid-dependent inmates or refer them to methadone programs upon release (Rich et al., 2005). One of the barriers to MMT involves concern about the appropriate length of time to administer MMT. Research has shown use of methadone for 8 months or longer reduces recidivism and other health problems, while MMT for periods of five months or less is associated with increased risks of recidivism and hepatitis C infection (Dolan et al., 2005). MMT is administered to stabilize individuals and enable them to be abstinent, which allows individuals to make lasting, behavioral changes. Each individual will require different amounts of medication and duration to be effective.

| For more information on Pharmacotherapy: American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry www.aaap.org American Osteopathic Association www.osteopathic.org American Psychiatric Association www.psych.org American Society of Addiction Medicine www.asam.org Center for Substance Abuse Treatment’s Division of Pharmacologic Therapies www.dpt.samhsa.gov/medications/medsindex.aspx National Institute of Drug Abuse www.drugabuse.gov |

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist that can alleviate cravings and withdrawal symptoms. In addition to treating heroin addiction, Buprenorphine may also be used to treat addiction to prescription opioids such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, and codeine. While Methadone is not prescribed in primary care settings for the treatment of addiction, Buprenorphine is available by prescription. Prescribing physicians do not have to be addiction specialists but must be specifically trained in the administration of buprenorphine before they are able to prescribe buprenorphine and are limited to prescribing buprenorphine to 100 patients. The availability of Buprenorphine by prescription from primary care physicians, psychiatrists, and specialty care physicians (such as infectious disease, cardiology, and obstetrics-genecology) presents many advantages to patients. For example, it increases the availability and accessibility of treatment for opioid dependence, reduces stigma, and increases physician’s capacity to treat co-occurring mental or physical health problems (McCance-Katz, 2004).

There are two preparations of Buprenorphine: (1) Suboxone®, which is buprenorphine combined with the opioid antagonist naloxone and (2) Subutex®, which is Buprenorphine alone. Research has shown that Subutex and Suboxone decrease drug use (17.8% and 20.7% respectively) compared with placebo (5.8%) (Fudala, 2003). Suboxone is primarily used in the United States.

Naltrexone (ReVia, Vivitrol, Depade) is a synthetic opiate antagonist with few side effects. It is FDA-approved for treatment of alcohol and heroin addiction. Naltrexone has no potential for abuse and is not addicting. Naltrexone blocks the effects of opiates like heroin and prevents the euphoric effects of other opiates. If other opiates are used while on naltrexone, the individual experiences a less desirable effect that gradually results in breaking the habit of opiate addiction.

Naltrexone (ReVia, Vivitrol, Depade) is a synthetic opiate antagonist with few side effects. It is FDA-approved for treatment of alcohol and heroin addiction. Naltrexone has no potential for abuse and is not addicting. Naltrexone blocks the effects of opiates like heroin and prevents the euphoric effects of other opiates. If other opiates are used while on naltrexone, the individual experiences a less desirable effect that gradually results in breaking the habit of opiate addiction.

Naltrexone is effective in preventing relapse and reincarceration. A study of opioid-dependent federal probationers participating in a 6-month program of probation plus Naltrexone and brief drug counseling found only 26% of those receiving Naltrexone were reincarcerated compared to 56% of the control group, which only received counseling (Cornish et al., 1997). As with Naltrexone use for alcohol addiction, poor compliance with oral Naltrexone has resulted in disappointing treatment results. A recent study found long-acting, injectable Depot Naltrexone to be safe and effective in retaining patients in treatment (Comer et al., 2006). There is a study currently underway examining the effectiveness of using Depot Naltrexone with heroin addicts on parole to determine its effectiveness in relapse prevention and eliminating craving. When available, it has been proposed to make treatment with Depot Naltrexone an option in the disposition of non-violent drug offenders whose charges are resolved by plea negotiations.

HEALTH AND SOCIAL SERVICES

Effective treatment must address a variety of social and environmental factors that compound the difficulty of overcoming alcohol and other drug problems. Many individuals with substance use disorders have multiple financial responsibilities—child support, family obligations, job requirements, and restitution—which can be major obstacles to participating in treatment and achieving and maintaining sobriety. To the extent the treatment and justice systems are able, it is important to assist individuals to meet their basic needs, including disease prevention and treatment, housing, and job training. Social services can be ordered as a condition of bail/release, probation, and parole to enhance the likelihood of successful completion of treatment and probation/parole.

For more information on substance abuse treatment for individuals with HIV/AIDS: CSAT’s TIP 37 Substance Abuse Treatment for Persons with HIV/AIDS Drugs, Alcohol and HIV/AIDS: A Consumer Guide Drugs, Alcohol and HIV/AIDS: A Consumer Guide for African Americans |

Disease Prevention and Treatment Treatment planning for drug abusing offenders who are living in or re-entering the community should include strategies to prevent and treat serious, chronic medical conditions, such as HIV/AIDS, hepatitis B and C, and tuberculosis. The rates of infectious diseases, such as hepatitis, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS, are higher among individuals with substance use disorders, incarcerated individuals, and those under community supervision than in the general population. Infectious diseases affect not just the individual, but also the justice system and the community at large. Justice staff working with individuals with serious medical conditions should work with them to identify and access appropriate healthcare services, encourage compliance with medical treatment, and re-establish their eligibility for health services such as Medicaid (NIDA, 2006).

Housing Stable living arrangements are crucial to successful treatment. However, a lack of stable housing is a major challenge for individuals re-entering the community from the justice system. Additionally, alcohol and other drug problems are common among homeless populations and lead to morbidity and mortality and may perpetuate homelessness (Kertesz et al., 2003). Therefore, housing issues should be addressed as part of treatment planning.

Job Training and Placement Research shows individuals who are employed are more likely to remain in treatment and, therefore, less likely to recidivate. Job training and placement should begin at the start of treatment (Wexler, 2001). Job training and placement play a significant role in preventing relapse in preparation for re-entry back into the community after treatment and incarceration.

For more information on job training and employment issues: CSAT’s TIP 38 Integrating Substance Abuse Treatment and Vocational Services |

Treatment Retention

Staying in treatment is important not only to the health of individuals with alcohol and other drug problems but also to public safety. There are a number of factors that influence whether an individual will stay in treatment or not, including treatment readiness, treatment appropriateness, pressure from an outside source like the justice system or an employer, and family involvement in treatment (CSAT, 2005a).

Attention to individual needs Referring an individual to treatment that appropriately addresses their needs improves the likelihood that the individual will successfully complete treatment, saving lives and limited resources. However, the justice system is not always able to identify effective treatment but clinical experts can identify clients’ needs and define the appropriate treatment. Access to clinical expertise can help the justice system provide individuals and their families with the appropriate resources to address their problems, improving medical and legal outcomes.

For more information on culturally competent substance abuse treatment: |

Treatment should be modified as needed to meet the individual’s specific needs. Severity of alcohol or other drug problems, criminal history, gender, culture, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, language, literacy, and physical or cognitive ability may affect how an individual responds to treatment and should be considered during clinical assessment and throughout treatment.

Individuals with substance use disorders should be placed in treatment programs with the appropriate structure and level of intensity based on the severity of their problems, not based on their criminal charge (Taxman et al., 2007a). Participation in drug treatment in state and federal prisons increased between 1997 and 2004 as a result of increases in participation in mutual-help groups, peer counseling, and drug abuse education programs (Mumola and Karberg, 2006). However, “drug-involved offenders are likely to have dependence rates that are four times greater than those among the general public, the drug treatment services and correctional programs available to offenders do not appear to be appropriate for the needs of this population” (Taxman et al., 2007b). With limited amount of resources available, it is important to ensure that the most appropriate resources are used.

For more information on evidence-based treatment approaches for individuals with alcohol and other drug problems in the criminal justice system: |

Another concern is that while most programs have been developed specifically for men there has been a significant increase in the number of females entering the justice system. Though the female prison population is growing faster than the male prison population, few treatment programs have been developed specifically for female offenders, and many of the programs that do exist for women in jails and prisons are based on treatment models developed for male offenders (Peters et al., 1997). Research has shown that females are more likely than males to have a mental health disorder and trauma-related problems in addition to a substance use problem. They are also more likely to be affected by poverty, physical or sexual abuse, unstable social supports, and medical problems like HIV.

Research of women in jail-based substance abuse treatment programs suggests that such programs should be designed to meet individual needs wherever possible (Peters et al., 1997). There needs to be sufficient time set aside for the assessment and diagnosis of co-occurring disorders and for teaching a range of skills (i.e., parenting, nutrition and health care, accessing social services and housing) that are generally not considered as important in treatment programs for male offenders (Peters et al., 1997). Treatment for women may present the additional challenge of providing care for children. It is important to involve family members in treatment when possible and establish agreements with relevant child welfare agencies (CSAT, 1999).

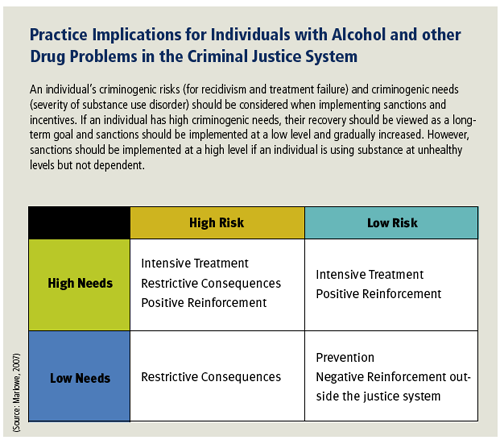

Incentives and Sanctions The conventional justice model offers incentives and sanctions. Under such a model, specific findings such as a positive urinalysis are often met with sanctions. Such sanctions are imposed with the assumption that drug consumption is undertaken rationally and with freedom of choice. However, research suggests that some instances of drug use result from biological urges that an individual may be unable to control (CSAT, 2005).

ASAM Patient Placement Criteria |

Incentives and sanctions may be used creatively to keep an individual in treatment. Incentives, or positive reinforcement, are easier to implement, have less negative side effects, and may have more positive results. There is a broad array of incentives, including reduced supervision and increased access to other services like job training or improved housing. Both treatment and justice staff should strive to focus on reinforcing desired behavior and continue to search for innovative ways to motivate and engage individuals from a positive perspective (CSAT, 2005).

For more information on incentives and sanctions: |

Family Legal and alcohol and other drug problems are not only individual problems—they have a tremendous impact on families. Family courts strive to handle all cases in a holistic way, treating alcohol and other drug and related problems as a family issue. This approach requires flexibility and a broad understanding of addiction, especially relapse and prevention. It is important for the justice system not to make decisions based solely on allegations of substance abuse. Screening is an important tool to evaluate alleged or suspected alcohol and other drug problems. However, a positive screen should not necessarily result in negative reinforcements such as a judge removing a child from a parent’s custody. Such actions could contribute additional stresses that increase the difficulty of successfully completing treatment. Additionally, justice staff have a role in preventing the cycle of alcohol and other drug problems by discussing prevention with children of individuals involved in the justice system. Recent research indicates that parental criminal justice involvement and parental substance abuse increases the likelihood that a family will experience economic strain and unstable home and school conditions (Philips et al., 2007).

Educational approaches providing help for families involved with the court system are currently being developed by: Family Justice www.familyjustice.org |

Family involvement in treatment can be a key element of effective treatment for alcohol and other drug problems (O’Farrell, 1993). Two examples of family involvement in treatment are family drug courts and family case management. Family drug treatment courts are effective at retaining parents in treatment, quicker reunification with children, and reduced child abuse and neglect recidivism (Worcel et al., 2006). Family case management is a valuable tool for families because addressing their alcohol, other drug, and related problems often involve multiple systems. Family case management has been shown to decrease drug use even though treatment dosages did not change (Sullivan et al., 2002).

Additionally, reintegrating with family after treatment at a rehabilitation center or a correctional facility can be a powerful source of strength for an individual in recovery. However, it is also possible that the home environment may threaten the individual’s treatment progress by providing stressors, such as health or financial problems and exposure to others who are abusing substances. Domestic violence and child abuse situations present additional issues, including the personal safety of family members. Justice system and treatment staff should assess the home environment when defining a treatment plan not only to identify these threats, but also to proactively look for positive family support.

Continuing Care

When formal treatment is completed, continuing care is critical to success. When possible, justice personnel should arrange for continuing care beyond treatment and when re-entering the community. Sometimes it can take as little as a phone call to a physician or hospital, depending on the availability of local resources. Continuing care is important because many problems become more apparent only when an individual returns to the community following inpatient treatment or incarceration. Such activities include learning to handle situations that could lead to relapse; learning how to live substance-free in the community; and developing a substance-free peer support network (NIDA, 2006).

Research shows that the first 3-6 months after treatment are the most vulnerable time period for relapse to occur. Continuing care services can be provided through individual, group, and family therapy and are often scheduled monthly. In some cases telephone counseling has been shown to effectively prevent relapse.

Continuing care is especially important for individuals involved with the justice system, because research shows that 30% of offenders had evidence of substance use within the first 2 months after their release from prison (Pelisser et al., 2007). Another study illustrated that in-prison treatment programs reduced recidivism by about 5%, while in-prison treatment with continuing aftercare treatment reduced recidivism by about 7% (Aos et al., 2006).

For more information on family, alcohol and other drug problems, and treatment: |

An important aspect of continuing care is relapse prevention. Relapse prevention plans provide ways to avoid exposure to triggers and high-risk situations and how to manage these situations if they are unavoidable. High-risk situations, like family conflict or being in places where and with people whose previous substance use occurred, trigger the brain to crave the substance of abuse.

Relapse prevention and recovery maintenance plans are often used by community-based treatment programs to develop a coordinated approach between probation/parole and treatment. These plans are also used in a number of drug and DWI courts. Drug and DWI courts help develop consensus among court, supervision, and treatment staff about an individual’s current “risk” level for relapse and in organizing responses to critical incidents and problem behaviors. Sanctions, incentives, and treatment should be adjusted accordingly to decrease risk factors, prevent relapse, and maintain recovery.