British Reconnaissance The Peace of 1763 ended the French and Indian War, with Britain victorious and France and her ally, Spain, the losers. In return for Havana, which the British had captured in 1762, Spain ceded Florida to Great Britain. The British divided the ceded colony into two provinces, East and West. In talks with Florida Creeks, British authorities promised to restrict white settlement in East Florida to the area south of the St. Mary’s, east of the St. John’s, and north of New Smyrna, thus extending the Proclamation Line of 1763 that attempted to protect the tribes from British settlers’ unfettered expansion into their territory. Hardly had the cession of Florida been completed when the British began to make plans for its development. Promoters rushed into print and speculators grew giddy, but the reconnaissance of the newly acquired territory was very thorough. |

||

48. Archibald Menzies. Proposal for peopling his Majesty’s southern colonies on the continent of America. Magerny Castle, Perthshire, Scotland, 23 October, 1763. |

||

49. William Stork. An account of East-Florida with remarks on its future importance to trade and commerce. London, [1766]. We shall see this illustrated, by comparing the commerce of the two small islands of St. Christopher, and Rhode-Island, both of them well settled, and well cultivated; both fertile, and almost of the same size; the principal difference betwixt them consisting in this, that the former is situated in lat. 17. and the latter in 41. Let an estimate be made of the annual exports of each; by comparing them together we discover at once the difference that is made by climate only: the exports of the former are of great value, and of the latter very little. |

||

50.“Observations of Denys Rolle.” In: William Stork. An extract from the account of East Florida published by Dr. Stork, who resided a considerable time in Augustine. London, 1766. |

||

51. Thomas Jefferys, “Map of East Florida.” In: Dr. William Stork. A description of East Florida with a journal kept by John Bartram. London, 1769. |

||

52. Pedro Diaz. "Mapa topografico de la Florida." Manuscript. 1769. This Spanish manuscript map is a bit of a puzzle. Was it part of the “tool kit” for a hoped-for re-possession of Florida sometime in the future? On first glance it appears to be crowded with information about the nature of the Florida interior, Indian villages, etc., but closer examination, and comparison with the contemporary maps shown in this case, suggest that the Spanish cartographer drawing this map in Havana was geographically very much out of touch with British geographical knowledge of Florida in 1769. |

||

53. “A map of the American Indian nations.” In: James Adair. The history of the American Indians, particularly those nations adjoining to the Mississippi, East and West Florida. London, 1775. |

||

54. Bernard Romans. Proposals for printing by subscription, three very elegant and large maps of the navigation, to, and in the new ceded colonies. Philadelphia, August 5, 1773. |

||

55. Bernard Romans. Concise natural history of East and West Florida. New York, 1775. |

||

Florida Restored to Spain Spain entered the American Revolution in 1779 as an ally of France against Great Britain, with the goal of restoring losses they had suffered in the Peace of 1763 on the losing side of the Seven Years War. The governor of Spanish Louisiana, Count Bernardo de Gálvez, led a series of successful offensives against the British forts in the Mississippi valley, then turned his attention to Pensacola, capital of British West Florida. Gálvez's forces achieved a decisive victory against the British in 1781 at the Battle of Pensacola, which gave the Spanish control of West Florida once again and ensured the return of Florida to Spain in the Peace of 1783. |

||

|

56. “Dom. Serres. A north view of Pensacola on the island of Santa Rosa.” In: William Roberts. An account of the first discovery, and natural history of Florida. London, 1763. |

|

|

57. “Plan of the fort at Pensacola in West Florida 1764.” In: [French and Indian War field diary. 1756-1765]. Manuscript. |

|

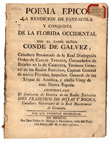

58. Francisco Rojas y Rocha. Poema epico, la rendicion de Panzacola y conquista de la Florida Occidental por el exmô. Señor Conde de Galvez. Mexico City, 1785. |

||

59. The case of the inhabitants of East Florida with an appendix containing papers by which all the facts stated in the case are supported. St. Augustine: John Wells, 1784. |

||

Epilogue, post 1783 |

||

| RETURN to this exhibition's Home page. | ||

Exhibition may be seen in THE Reading Room from january through Exhibition prepared by Amy Turner Bushnell, Independent Research Scholar, and Susan Danforth, Curator of Maps, John Carter Brown Library. |

![]()

| Images: "Map of Florida," Theodor de Bry, America, pt 2 (1591); "Plan of Pensacola," [French and Indian War field diary. 1756-1765]. (1764); "Mapa topografico de la Florida lo dibuxo Pedro Diaz ano de 1769 por mandato Ilmo Senor Don Jose Puerto Llano y Canales" (1769). |

|---|