| |

August 2015

The CODEX SP 61 and the FRANCISCAN KNOWLEDGE PRODUCTION

of WESTERN AMAZONIA

Roberto Chauca

2014-2015 Jeannette D. Black Memorial Fellow

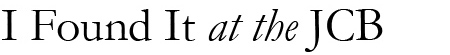

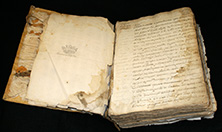

The John Carter Brown Library is renowned for its large and impressive collection of printed materials about the history of the early Americas. Yet, it also contains a reduced, but selected, group of manuscripts. One of these is the Codex Sp 61. This is a 460-leaf volume containing 4 documents with relevant information for the study of the social, geographical, and political situation of what is now eastern Peru during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

|

|

Click image for enlargement. |

The entire volume seems to have been reunited around the end of the eighteenth century by the hand of a Franciscan friar of the Province of Peru, presumably Manuel Sobreviela, with an interest in preserving reports and documents about the human and spatial conditions in Western Amazonia. We must remember that since the seventeenth century this tropical region had become a laboratory of evangelization and colonization by Jesuit friars from Quito, around the Napo and Marañon Rivers in what was then known as Maynas, and Franciscans from Peru, around the Huallaga and Ucayali Rivers.

The first two documents, “Copia de las Reales Ordenes sobre el Mayro” and “Noticias interesantes sobre Chanchamayo” contain transcriptions of documents, from 1754 to 1790, related to the exploration of a route connecting the center of Peru with the Ucayali River via the Mayro River and with the maintenance of a military station in Chanchamayo, respectively. These documents consists of reports sent by local officials and Franciscan missionaries that discussed different aspects of the Mayro and Chanchamayo enterprises as well as the responses from Viceregal authorities in Lima on those matters.

I find these documents particularly important because they show the entire project of colonization of the eastern flanks of the Viceroyalty of Peru and the different interests, from governmental officials and missionary authorities, which were at stake in such enterprise. Likewise, for someone interested in the crafting of missionary geographic and cartographic knowledge of Amazonia like me, these reports are vital to assess the role Franciscans played in the construction of such knowledge and how it was received, debated, approved, or disapproved among missionaries themselves and, more important, among authorities of the Viceroyalty in Lima.

The third document, “Informe sobre las misiones de Maynas echo por el padre Francisco de Figueroa de la extinguida Compañia de Jesus” is a transcription that the Franciscan Manuel Sobreviela presumably made in 1791 of the 24 chapters of the original 1661 account that the Jesuit Figueroa had written about the missionary presence of the Society in Western Amazonia since 1637. The Franciscan Narciso Girbal had brought an original copy of Figueroa’s Informe from one of his trips to the town of Laguna, former missionary capital of the Jesuit missions in Maynas and located near the intersection of the Marañon and Huallaga Rivers. It is also probable that in this same trip Girbal brought a copy of another report whose transcription constitutes the fourth document of Codex Sp 61: “Relacion de la entrada que hizo á la Nacion Pana, subiendo por el Ucayale , el Presbytero Don Pedro de Valverde, Superior, Visitador, y Vicario General de las Missiones de Maynas.” Valverde’s Relación seems to have been written in Laguna around 1789 and, although it remains unconcluded, it provides important information about the the Upper and Middle Ucayali, as well as descriptions of local Panoan and Conibo societies. These two documents demonstrate that the construction of the geographic and ethnographic knowledge of Western Amazonia transcended missionary affiliations and that late-eighteenth-century Franciscans from the Province of Peru came to depend on the knowledge that Jesuit friars and secular priests from the Audiencia of Quito had gathered about such region since the seventeenth century.

Together the four documents in Codex Sp 61 shed a fascinating glimpse into the human and spatial landscape of early modern Western Amazonia and reveal the different points of view, from missionaries and officials, which became the foundations of the knowledge on the tropical heartland of South America. |

|