Laboratory Primate Newsletter

Laboratory Primate Newsletter  Laboratory Primate Newsletter

Laboratory Primate Newsletter VOLUME 44 NUMBER 3 JULY 2005

Printable (PDF) Version of this issue

Articles and Notes

Does Training Chimpanzees to Present for Injection Lead to Reduced Stress? by E. N. Videan, J. Fritz, J. Murphy, S. Howell, & C. B. Heward......1

A Preliminary Test of the Van Schaik Model of Male Coalitions for Costa Rican Mantled Howler Monkeys (Alouatta palliata), by C. B. Jones......3

Nonhuman Primate Feeding Schedules: A Discussion......6

Silky Sifaka (Propithecus candidus) Conservation Education in Northeastern Madagascar, by E. R. Patel, J. J. Marshall, and H. Parathian......8

Agonism and Affiliation: Adult Male Sexual Strategies Across One Mating Period in Three Groups of Long-Tailed Macaques (Macaca fascicularis), by J. E. Loudon, A. Fuentes, and A. R. Welch......12

News, Information, and Announcements

Information Requested or Available......2

World Animal Net Directory; More Interesting Websites

Awards Granted......5

. . .

2004 Conservation Award to Rwandan, Kenyan; Marc Bekoff Receives Community Service Award

Calls for Award Nominations: New Prizes for Work on Alternative Methods......5

Research and Educational Opportunities: Residency/Graduate Training......7

Travelers� Health Notes: International Assn for Medical Assistance to Travelers......15

Southeast Asian Primatological Association Established......17

Electronic Freedom of Information Act Availability of Annual Reports......17

Meeting Announcements......18

Workshop Announcements......18

. . .

2006 International Gorilla Workshop; Meeting the Information Requirements of the AWA; IACUC 101 and Beyond

Volunteer Opportunities......19

. . .

Year-Round Volunteer Internships; Primate Behavior Field Assistant � Ecuador

Resources Wanted and Available......20

. . .

New Environmental Enrichment Site; PASA Veterinary Healthcare Manual in French; New Report on Most Endangered Primates

Grants Available: Simian Vaccine Evaluation Units......20

Announcements from Publications......22

. . .

BMC Veterinary Research; Veterinary Virology

News Briefs......23

. . .

Anne Yoder Named Duke Primate Center Director; Study Will Debate Monkey Future in U.K.; Three Francois Langurs Die at Lincoln Park Zoo; Last of the Bonobos Arrive at Great Ape Trust; Animal Rights Museum in Madison

Departments

Primates de las Am�ricas...La P�gina......16

Positions Available......21

. . .

Facility Manager � Vanderbilt Medical Center; Clinical Veterinarian � Yerkes; Veterinarian � Alice, Texas; Vet or Animal Health Tech � Metro Boston Area; Manager, Technical Operations � Bethesda

Recent Books and Articles......24

* * *

Does Training Chimpanzees to Present for Injection Lead to Reduced Stress?

Elaine N. Videan(1), Jo Fritz(1), James Murphy(1), Sue Howell,(1) and Christopher B. Heward(2)

(1)Primate Foundation of Arizona and (2)Kronos Science Laboratories

Introduction

Using positive reinforcement to train primates to cooperate during routine health procedures is thought to be preferential to forced compliance, such as the use of restraints (Prentice et al., 1986). Involuntary anesthesia injections (i.e., darting) may result in stress to the animal, leading to blood samples that are not physiologically representative of the individual�s normal hormone levels during non-stress periods (Reinhardt et al., 1995). A recent study indicated that training chimpanzees to present for anesthesia injection results in lower levels of some physiological stress responses, in particular significantly lower white blood cell counts and glucose levels (Lambeth et al., 2004). However, simple comparison of individuals who are darted for a health examination versus those that allow anesthesia injection may ignore other factors leading to stress during the procedure. Individuals that will not present for injection upon verbal command, but will present when shown the dart gun, may experience stress levels at or above those of darted individuals.

The purpose of this study was to compare serum cortisol and other physiological stress responses (white blood cell counts and blood glucose levels) in a sample of captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) that experienced difficult versus easy anesthesia injections. We predicted that injected chimpanzees would have significantly lower levels of stress-related serum values than darted chimpanzees, as found by Lambeth and colleagues (2004). We also predicted that easily immobilized chimpanzees would have significantly lower levels of stress-related serum values than more uncooperative individuals. Finally, we predicted that trained individuals would have significantly lower levels of stress-related serum values than untrained individuals.

Methods

Subjects were 17 captive chimpanzees living at the Primate Foundation of Arizona, aged 10.6 to 34.5 years at the time of the study. The sample included 8 males and 9 females. Eleven of the subjects were trained, using positive reinforcement techniques, over 21 months (Videan et al., 2005). Individuals were trained to present an arm or leg to the cage mesh for anesthetic injection, using the verbal cues �arm� and �leg�. Training procedures were transferred from the trainer to either the colony manager or the assistant colony manager, after behaviors were under stimulus control, in 5 of the trained subjects.

Data from one semiannual health examination, including a blood test, were collected for each individual. Data recorded included whether the individual presented for anesthesia injection or required darting, and the difficulty of the anesthetization (level of cooperation). Difficult-to-anesthetize chimpanzees (�uncooperative�) were defined as those who avoided the needle and/or dart and required multiple injection and/or darting attempts. Blood chemistry values associated with physiological stress, including white blood cell (WBC) counts, glucose levels, and cortisol, were compared between darted and injected, trained and untrained, and cooperative and uncooperative animals using one-tailed Mann-Whitney U-tests. Blood chemistry values were compared between trained-transferred, trained-untransferred, and untrained individuals using a Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance. Significance for all tests was set at the 0.05 level.

Results

There were no significant differences in levels of cortisol (U=22, p>0.10), WBC (U=29, p>0.10), or blood glucose (U=22, p>0.10) between injected and darted chimpanzees (Table 1). However, significantly lower levels of both cortisol (U=6.5, p<0.010) and blood glucose (U=13, p<0.025) were found in individuals whose anesthetizations were ranked as easy or cooperative (Table 1). When all trained individuals were pooled, trained subjects exhibited significantly lower levels of cortisol than untrained (U=7, p<0.010, Table 1). Finally, trained and transferred subjects exhibited significantly lower levels of cortisol than both the trained-untransferred and untrained chimpanzees (H=7.86, p<0.25, Table 1).

| Group | Cortisol (ug/dl) | WBC Counts (th/mm3) | Glucose (mg/dl) |

| Darted (n=10) | 24.11 +/- 6.00 | 9.46 +/- 5.82 | 97.70 +/- 13.33 |

| Injected (n=7) | 21.24 +/- 5.38 | 7.33 +/- 1.90 | 90.43 +/- 7.37 |

| Uncooperative (n=8) | 26.24 +/- 4.98 | 9.70 +/- 6.08 | 100.00 +/- 11.96 |

| Cooperative (n=9) | 19.20 +/- 4.18 | 7.33 +/- 1.94 | 88.75 +/- 8.14 |

| Trained-Transferred (n=5) | 17.66 +/- 4.91 | 11.06 +/- 8.01 | 96.60 +/- 19.92 |

| Trained-Untransferred (n=6) | 22.75 +/- 4.62 | 6.68 +/- 1.14 | 94.33 +/- 8.02 |

| All trained (n=11)) | 20.44 +/- 5.23 | 8.67 +/- 5.62 | 95.36+/-13.87 |

| Untrained (n=6) | 27.50 +/- 3.57 | 8.42 +/- 2.46 | 93.50 +/- 6.44 |

Table 1: Mean (+/- standard deviation) cortisol levels (ug/dl), white blood cell (WBC) counts (th/cu-mm), and blood glucose (mg/dl) levels for darted versus injected (not darted), uncooperative versus cooperative, and trained versus untrained chimpanzees. Significant differences are in bold.

Discussion

Blood chemistry values indicate that presenting for injection does not necessarily lead to lower stress levels in a chimpanzee than darting. However, the training process appears to decrease the stress associated with the anesthesia event. The trained-transferred chimpanzees had the lowest levels of cortisol, despite two of these individuals requiring darting during their anesthetization. Results of training itself also indicate that chimpanzees who are transferred from the trainer to the colony managers retain their training at significantly higher rates than non-transferred chimpanzees (Videan et al., 2005). It could be that the trained-transferred animals are becoming generally more comfortable with (i.e. habituated to) novel circumstances presented by multiple individuals than the untransferred animals.

Finally, it is clear that the level of cooperation must be considered an important factor in determining the amount of stress experienced during anesthetization. Those chimpanzees whose anesthetizations were considered �easy� experienced significantly lower levels of stress, independently of whether they eventually presented for injection or required darting. Simply classifying anesthetizations as �injected� versus �darted� does not capture the level of stress experienced by the chimpanzee. Further research should examine other variables (e.g., temperature, colony noise level, identity of staff present, etc.) to more completely assess the factors causing stress during anesthetization in chimpanzees.

References

Lambeth, S. P., Hau, J., Perlman, J. E., Martino, M. A., Bernacky, B. J., & Schapiro, S. J. (2004). Positive reinforcement training affects hematologic and serum chemistry values in captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). American Journal of Primatology, 62[Suppl.1], 37-38.

Prentice, E. D., Zucker, I. H., & Jameton, A. (1986). Ethics of animal welfare in research: The institution�s attempt to achieve appropriate social balance. The Psychologist, 29, 1 and 19-21.

Reinhardt, V., Liss, C., & Stevens, C. (1995). Restraint methods of laboratory nonhuman primates: A critical review. Animal Welfare, 4, 221-238.

Videan, E. N., Fritz, J., Murphy, J., Borman, R., Smith, H. F., & Howell, S. (2005) Training chimpanzees to cooperate for an anesthetic injection. Lab Animal, 34, 43-48.

* * *

Information Requested or Available

World Animal Net Directory

World Animal Net Directory, which lists more than 15,000 animal protection organizations in 165 countries, is now available in both English and French. The 550-page book can be purchased for US$29.95 / Euros 24.2 / sterling 16.4 (plus US$5 / Euros 4.1 / sterling 2.7 shipping & handling) at <www.worldanimal.net>; or contact <[email protected]>.

More Interesting Websites

* * *

A Preliminary Test of the Van Schaik Model of Male Coalitions for Costa Rican Mantled Howler Monkeys (Alouatta palliata)

Clara B. Jones

Fayetteville State University and Community Conservation, Inc.

Introduction

In mantled howler monkey (Alouatta palliata) societies, conflicts arise because interindividual interests differ (Jones, 2000). Darwin (1871; also see Dixson, 1998; Jones & Agoramoorthy, 2003) proposed that, among males, �male-male competition� (intrasexual selection) would determine access to and monopolization of females. Although most competitive interactions among male mantled howlers are dyadic, coordinated attacks by two males against a third have been observed (Jones, 1978, 1980, 1985, 2000). In this communication, I present a reinterpretation of these coalitions as a preliminary test of a recent model of male-male within-group coalitionary aggression (the van Schaik model: van Schaik et al., 2004).

Van Schaik and his colleagues (2004) proposed that coalition value �is the sum of the payoffs of the partners in their original ranks� (p. 101). Although not explicitly stated by these authors, �payoffs� will be condition-dependent since individual optima are expected to change from situation to situation (e.g., according to the �value� of the resource or the quality of the target male). It is also important to note that the symmetry in value among coalition partners need not be equivalent, and that the likelihood of coalition formation among males may be inversely related to rank distance between them, all other things being equal. Van Schaik et al. (2004) propose five �basic coalition types�: (1) rank-changing coalitions targeting individuals ranking above all coalition partners; (2) rank-changing coalitions in which higher-rankers support lower-rankers to rise to a rank below themselves; (3) non-rank-changing coalitions, expected to occur whenever high-ranking males have low-ranking close relatives; (4) non-rank-changing coalitions by high-rankers against lower-ranking targets; and, (5) non-rank-changing coalitions in which all partners rank below their target and which flatten the payoff distribution. The present analysis suggests that, consistent with the van Schaik model, adult male mantled howler monkeys exhibit a variant of configuration #2 in addition to configurations #1 or #5. The possible implications of these findings for social evolution in mantled howlers is discussed.

Methods

The study was conducted in 1976 and 1977 at Hacienda La Pac�fica, Ca�as, Guanacaste, Costa Rica (10�18� N, 85�07� W). Results are based upon randomized focal (Altmann, 1974) and ad lib. observations. Modal social organization of mantled howlers is multimale-multifemale, yielding a polygynandrous mating system (Jones, 1978, 1980, 2000). Two marked groups, of known ages, were studied in two habitats of seasonal, tropical dry forest environment, riparian and deciduous (Frankie et al., 2004). Coalitions among males were observed only in the riparian habitat group (Group 5, 402 h observation: Y male, highest ranking; G male, second-ranking; R male, lowest-ranking; and, LT male, a young male entering the hierarchy in 1977). See Jones (1978, 1980, 2000, 2005, Chapter 6) for details of procedures and changes in male rank relations.

Results

Twenty-four coalitions were observed in Group 5, 12 between adult females and seven among adult males (Jones, 1980, pp. 396-397; Jones, 2000, pp. 10-12). Coalitions among adults, then, were within-sex events (intrasexual competition). Two of the male coalitions were exhibited between Y and LT against G, and five coalitions between G and R against Y.

Discussion

Interpretation of the coalitions between G and R against Y is relatively straightforward. This configuration represents either case #1 or case #5 of the van Schaik model. An interpretation consistent with case #1 is required to assume that the goal or motivation of coalitions between G and R is a rank change, presumably to eject Y from the group and elevate G and R in the hierarchy or to depose Y from his position as highest-ranking male. An interpretation based upon case #5 suggests that coalitions between G and R are non-rank-changing, leveling coalitions. Van Schaik et al. (2004) indicate that rank-changing coalitions are expected where contest competition is strong, as has been reported for male mantled howlers in riparian habitat (Jones, 1978, 1980, 2000, 2005), supporting an interpretation based upon case #1. Nonetheless, both configurations #1 and #5 may occur since the exhibition of coalitions between G and R may be condition dependent. Sequence analysis is required to determine whether contexts and functions differ from coalition to coalition between these males.

Coalitions between Y and the young male, LT, appear to represent a variant of case #2 of the van Schaik model. These rank-changing coalitions are described by van Schaik et al. (2004) as coalitions in which higher rankers support lower rankers to rise to a rank below themselves and are expected to occur among relatives. G was ultimately expelled from Group 5 as a result of the coalition between Y and LT, who may have been Y�s son (Jones, 1980; C.P. van Schaik, personal communication, 2005). This mechanism of group ascension differs from that described by Clarke et al. (1994) who characterize a young male�s ascent to top rank as a process similar to that described for females (Jones, 1980). Both processes may occur in either sex of mantled howlers and may result from differing local (patch) conditions (e.g., differing mate or food quantity and/or quality).

Although a key feature of the coalitions between Y and LT appear to deviate from the van Schaik model (i.e., that rank-changing coalitions target individuals ranking above all coalition partners), further analysis resolves the apparent inconsistency. The adult male and female dominance hierarchies of mantled howlers are �age-reversed� (Jones, 1978, 1980) whereby young animals are highest-ranked, middle-aged individuals are medium-ranked, and old individuals are lowest-ranked. Consistent with the analysis of Beekman et al. (2003), coalitions between G and R may have imbalanced power relations in Group 5 from Y to G and R, making it beneficial for Y to form a coalition with LT to expel G and to settle for a reduction in dominance rank to second-ranked male below the young LT. This interpretation characterizes the �age-reversed� dominance hierarchy as evolutionarily stable and suggests one mechanism (coalitions between high-ranked and younger males entering a hierarchy) whereby stability might be maintained. This intuition requires theoretical (mathematical) modeling to reveal the logic of these intrasexual conflicts as well as empirical research to determine the ranges and thresholds of ecological regime and/or coefficients of relatedness (r) upon which hierarchical relations among males of this species depend.

It is important to note that coalitions among males, and probably among females, may be viewed not only as indicators of reproductive competition but also as mutual policing and suppression of competition within groups (Frank, 2003). The coalitions between G and R against Y as well as the coalition between Y and LT against G may be viewed as attempts by group members to manage the (condition-dependent) power and, thus, the social (reproductive) influence of other group members (Beekman et al., 2003; Jones, 2000). Additional research on the mechanisms of policing in mantled howlers may reveal important principles concerning the costs and benefits of social influence among primates and other social mammals, especially multimale-multifemale societies (e.g., humans). These studies will also contribute to our knowledge about reproductive skew since mutual policing may enforce �reproductive fairness� (Frank, 2003), at least over short terms. Finally, since coalitionary aggression is a form of punishment, future research should investigate �post-punishment responses� by the victim, responses (e.g., counter-coalitions) that may impose high costs upon the initial coalition partners (�spite�: see Jones, 2002).

References

Altmann, J. (1974). Observation study of behavior: Sampling methods. Behaviour, 49, 227-267.

Beekman, M., Komdeur, J., & Ratnieks, F. L. W. (2003). Reproductive conflicts in social animals: Who has power? Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 18, 277-282.

Clarke, M. R., Zucker, E. L., & Glander, K. E. (1994). Group takeover by a natal male howling monkey (Alouatta palliata) and associated disappearance and injuries of immatures. Primates, 35, 435-442.

Darwin, C. (1871). The descent of man. New York: The Modern Library.

Dixson, A. F. (1998). Primate sexuality: Comparative studies of the prosimians, monkeys, apes, and human beings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frank, S. A. (2003). Perspective: Repression of competition and the evolution of cooperation. Evolution, 57, 693-705.

Frankie, G. W., Mata, A., & Vinson, S. B. (2004). Biodiversity conservation in Costa Rica. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jones, C. B. (1978). Aspects of reproductive behavior in the mantled howler monkey (Alouatta palliata Gray). Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

Jones, C. B. (1980). The functions of status in the mantled howler monkey, Alouatta palliata Gray: Intraspecific competition for group membership in a folivorous Neotropical primate. Primates, 21, 389-405.

Jones, C. B. (1985). Reproductive patterns in mantled howler monkeys: Estrus, mate choice and copulation. Primates, 26, 130-142.

Jones, C. B. (2000). Alouatta palliata politics: Empirical and theoretical aspects of power. Primate Report, 56, 3-21.

Jones, C. B. (2002). Negative reinforcement in primate societies related to aggressive restraint. Folia Primatologica, 73, 140-143.

Jones, C. B. (2005). Behavioral flexibility in primates: Causes and consequences. New York: Springer.

Jones, C. B., & Agoramoorthy, G. (2003). Alternative reproductive behaviors in primates: Towards general principles. In C. B. Jones (Ed.), Sexual selection and reproductive competition in primates: New perspectives and directions (pp. 103-139). Norman, OK: American Society of Primatologists.

van Schaik, C. P., Pandit, S. A., & Vogel, E. R. (2004). A model for within-group coalitionary aggression among males. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 57, 101-109.

* * *

Awards Granted

2004 Conservation Award to Rwandan, Kenyan

Two wildlife champions, Michel Masozera, Rwanda country director for the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), and Ali Kaka, executive director of Kenya�s East African Wild Life Society, are this year�s winners of the National Geographic Society/Buffett Award for Leadership in African Conservation. Established through a gift from the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, the award recognizes outstanding work and lifetime contributions that further the understanding and practice of conservation in Africa.

Masozera, Rwanda country director for WCS since 2002, has worked tirelessly to document and preserve Rwanda�s rich biodiversity in the face of daunting socioeconomic challenges. Since 1997 he has led WCS�s Nyungwe Forest Conservation Project. Nyungwe Forest, home to 13 primate species, faces intense pressure because it is surrounded by some of the highest human population densities in Africa. To protect the forest from agricultural encroachment, hunting, logging, and gold mining, Masozera has implemented a multi-disciplined conservation program that has become a national model for protecting other threatened forests in Rwanda.

Based in Nairobi, Ali Kaka has been executive director of East African Wild Life Society (EAWLS) since 2001. EAWLS protects endangered and threatened species and habitats in East Africa and is at the forefront of community-based conservation initiatives. In the late 1990s, EAWLS, impeded by management problems, was in danger of collapse. Under Kaka�s leadership, the Society has reestablished its credibility and is a lead player in advocating for crucial policy change to enhance conservation practice in the region.

Recipients of the National Geographic Society/Buffett Award are chosen from nominations submitted to the National Geographic�s Conservation Trust. After the nominations are screened by a peer-review process, a selection of names is forwarded to the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, which recommends the final winner. Next year a similar award will introduced for conservationists in South America. � From National Geographic News, December 9, 2004

Marc Bekoff Receives Community Service Award

Marc Bekoff has been awarded the Bank One Colorado Corporation�s Faculty Community Service Award. This award recognizes his various, extensive efforts to draw attention to the plight of animals, and to inspire people to treat all animals more humanely. Marc is a local director of Jane Goodall�s outreach program, Roots and Shoots, which takes programs into the public schools. Animal awareness and rights have also been major themes of Marc�s extensive writing, including the books The Ten Trusts (with Jane Goodall), Minding Animals, and The Smile of a Dolphin.

The Award is given annually to a full-time faculty member at one of the campuses of the University of Colorado who has rendered exceptional educational, humanitarian, civic, or other service in his or her community, external to the faculty member�s primary university responsibilities and for no additional remuneration. � Announced by the University of Colorado, May 16

* * *

Calls for Award Nominations: New Prizes for Work on Alternative Methods

Two new prizes for research that advances alternative methods (the Three Rs of replacement, reduction, or refinement of animal use) are being offered this year. The Dieter Lutticken Award, sponsored by Intervet International, the animal health arm of drug-maker Akzo Nobel, recognizes outstanding contributions in the testing, development, and production of veterinary medicines. Intervet states that the scope of the 20,000-Euro award �covers in vitro models used in research and development which replace animal testing for licensing purposes, as well as studies avoiding the use of animals.� The application deadline is September 30, 2005.

The Australian and New Zealand Council for the Care of Animals in Research and Teaching (ANZCCART), the Australian Museum, and the Sherman Foundation have announced a new $10,000 prize designed to encourage research into alternatives to the use of animals or animal products for scientific or teaching purposes. The Voiceless Eureka Prize for Research will go to an Australian scientist(s) for work carried out in Australia in the past five years that has reduced, or has the potential to reduce, the use of animals in laboratory-based research, education and testing. Entries closed on May 13 this year. � From the HSUS�s e-mail publication, Animal Research News & Analysis

* * *

Nonhuman Primate Feeding Schedules: A Discussion

Bonnie Beresford, Director of Animal Care Services at Queen�s University, Kingston, Ontario [e-mail: [email protected]], wrote to CompMed: �A question on primates: ours are fed twice daily at about 8:30 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. � chow and fruit at both feedings. One primate protocol calls for the primates (cynomolgus) to be handled by the investigators before the morning feed, and the investigators are then supposed to feed the primates by 10:00 a.m. Frequently they do not arrive on time and the primates are not given their first feeding until later � 11:30 or noon. They are fed again by animal care staff at 3:00. Is this schedule problematic? The researchers claim that some institutions feed primates only once a day, so they are not concerned. I will appreciate any information on acceptable primate feeding schedules.�

Summary of Replies

* �At our facility, we feed biscuits in the morning and fruit in the afternoon. If the animals have a procedure that is to be done, we usually schedule it first thing in the morning, or whenever the PI or tech gets to the primate area (I have had problems with lateness as well). When the procedure is finished, I wait until they are awake and then feed them about � of their normal biscuit intake to reduce any risk of nausea or vomiting. Depending on how late they recover fully, I will decide if they get fruit in addition to biscuits (usually � the normal amount). I will also give � the fruit ration. Sometimes they recover so late that they only get the biscuits. I try to make the feeding times as far apart as possible to reduce chances of bloat as well as vomiting. I think that you should make exceptions to the feeding schedule for those animals that have had a procedure done; that way you could prevent any illness or injury and not be worried about over-feeding them. I have fed biscuits once a day for a long time and have had no problems, but the fruit is given in the afternoon. I understand the rationale for feeding twice a day, though. My main concern would be overfeeding at recovery, so having biscuits once a day on the day of a procedure may be the safest for the monkey as well. I have had monkeys that have had procedures done in the morning, been fed when awake, and still have biscuits left over in the afternoon! The feeding schedule may just have to be adjusted on a case-by-case basis. I hope that this helps.� (Kate Bullock BS, RVT, RLAT).

* �The researchers are not concerned about this because it�s not THEIR feeding schedule being ignored� I�ve always treated the animals as if reincarnation is possible, and the animal(s) might be my grandmother. Trust me, she would have wanted to eat more than once a day.� (Sherilyn Hall)

* �If the schedule is very irregular the animals are prone to bloat, which can be fatal if not corrected. This not especially common in adult cynomolgus, but can be a problem in juveniles or in other NHP species.� (Anonymous)

* �We have macaques (rhesus and cynomolgus) that are given 16 biscuits once daily (about 8:30 a.m.). Only about half of our cages have homemade puzzle feeders (open-top plexiglass feeders bolted to the front of the cage). For those with J-feeders, we throw the chow on top of the cage. We have a very small colony, and it almost always turns out that anyone without a puzzle feeder has access to a cage ceiling, either in his home cage or a play cage. So no matter what kind of feeder our guys have, foraging is necessary to obtain the biscuits. I find that there is much less hoarding and fewer biscuits are wasted when they have to work for their food.

�About feeding later than usual: If one animal is fasted for a surgery or procedure, we don�t feed the others in the room until that monkey is down. They may complain, because they know when to expect breakfast, but since we only feed once a day we don�t have a problem with meals being too close together. Fresh fruit or vegetables are given in the afternoon (about 3 p.m.).� (Rebecca Goertz, RLAT, Research Technician III, SUNY, State College of Optometry)

* �For what it�s worth, we are a commercial facility, housing anywhere from 300-1200 primates. We have always had a policy of feeding twice a day. First feeding consists of all monkey chow, and second feeding consists of a lesser amount of chow mixed with some fruit, treats, etc. However, while the above is common practice, I also don�t feel that in most cases, especially with cynomolgus, there is a severe risk to the animals with only one feeding but no doubt I personally prefer two.� (Anonymous)

* �NHP biscuits in the morning and fruit in the afternoon.� (Anonymous)

* �We feed chow once a day in the p.m., fruit in the a.m. Does the protocol require food deprivation? If so, then the delay is not a problem. If they are simply not showing up on time�� (T. deLangley)

* �I�ll be interested in hearing what feedback you get on this. I have a similar problem with some investigators. The reasoning behind twice daily (b.i.d.) feeding is that it helps prevent bloat. I haven�t seen bloat in these animals, but it is one of those �tucked away in the back of my mind� worries. I have a colony of >1,000 rhesus and we pretty much keep food in front of them at all times. Haven�t seen bloat in them, either. I did see it during my residency at another facility � usually in individually housed cynomolgus. I don�t remember whether we determined any predisposing factors.� (Anonymous)

* �While at XX and YY, I�d have my staff feed twice daily as long as we had adequate staff to do so (I let it slide during a couple of snow emergencies when less than 30% of staff was able to get to work). The only real reason I�ve found to feed primates twice daily is to avoid having them use the food they didn�t eat immediately as decorations for the cage and, if possible, the rest of the room.� (Anonymous)

* �Once-daily feedings can lead to medical problems in primates. Specifically, primates that are fed only once daily can be rather hungry and anxious when they finally do get their food and eat it quickly. This can lead to bloat and/or obstruction, which can be fatal (I have treated these type of cases in the past in rhesus and cynomolgus and was able to convince the investigator that it was not sound to feed in this manner).

�Physiologically, it is also abnormal for cynomolgus to eat once a day. In the wild, they are foraging for five to eleven hours and �grazing� continuously. We know from humans that feeding the daily calories in one feeding vs. feeding over the course of the day promotes obesity, even if the total number of calories is the same for both groups. It would not seem to be optimal for long-term maintenance of these animals (also issues of psychological stress).� (Anonymous)

* �Your biggest problem with once a day feeding is the chance of gastric bloat, but � with all due respect � that has been very rare with cynomolgus in all the places that I have worked. If your surgeries involve intra-abdominal manipulations than I would be worried about the other end, as I have had cecal dilatation as a sequela to surgery. Gastric bloat is much more common in rhesus. I have worked in facilities that have historically fed once per day with cynomolgus and they didn�t have problems (four years). I had always done b.i.d. prior and since as that is commonly the practice. I think that it at least makes the care staff check the animals twice a day!� (Elysse A. Orchard, Veterinarian and Associate Director, Chimp Haven)

* �I am sure that there are also institutions where ruminants are also fed just once a day and they survive. Twice a day feeding provides for one more incident of human contact and potential for socialization; is less wasteful in terms of food (many will toss food to the cage bottom and not want it after it�s been in the �trash bin�); is better for their nutritive well-being (ask your investigators to limit their own intake to once a day); if they are in a common colony room with other animals that do get fed twice daily, they are stressed about being left out; and finally � though I do not recall a research paper on this topic � the potential for bloat seems to be greater with a �once a day� engorgement than with twice daily feedings. � My two cents worth.� (Les Rolf, Jr., Ph.D., D.V.M., Staff Veterinarian, University of Pennsylvania/ULAR)

* �We feed squirrel monkeys once daily after all behavioral testing is complete; feeding can serve as a secondary Zeitgeber (an environmental agent or event that provides the cue for setting or resetting a biological clock) � hence, potential confound. We split rhesus feeding b.i.d., as risk for overeating bloat is too high in them.� (Anonymous)

* * *

Research and Educational Opportunities: Residency/Graduate Training

The NIH Intramural Research Program has resident/graduate training positions beginning with the August, 2005, academic year. The residency program is jointly sponsored by the NIH Office of Intramural Research (OIR) and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU).� The program consists of a two-year graduate program of instruction in Comparative Medicine, culminating in a Master of Comparative Medicine degree from USU, and a concurrent residency experience in laboratory animal medicine (LAM) offered in NIH research facilities.

During the residency, the resident obtains supervised practical experience and completes research leading to a published first-author paper.� The USU program in Comparative Medicine includes didactic instruction in LAM, meeting the standards of an ACLAM-approved residency program.

This program has a dual application process; therefore prospective residents must complete application packets from both the Graduate Partnerships Program (at <gpp.nih.gov>) and the Office of Graduate Education, USU (at <cim.usuhs.mil/geo/application.htm>).�� A competitive selection will be made by the NIH Residency Faculty Committee, based on prior academic performance, letters of reference, goals for graduate study, and career plans in laboratory animal medicine. Residents will be supported for stipend, medical insurance, and tuition for the two-year period of the program (depending on satisfactory progress). For more information contact Dr. Marlene N. Cole, Director, NIH-USU LAM Resources Program [e-mail: [email protected]].

* * *

Silky Sifaka (Propithecus candidus) Conservation Education in Northeastern Madagascar

Erik R. Patel1, Jennifer Joyce Marshall, and Hannah Parathian

1Department of Psychology, Cornell University

Introduction

The president and senior staff of Conservation International recently pointed out that �In terms of primate conservation, there is no doubt that Madagascar is the world�s single highest conservation priority� (Mittermeier et al., 2003, p. 1538). With five primate families found only on this island nation, Madagascar�s degree of primate endemism is more extreme than that of any other nation. This fact is reflected in the estimated 257 million years of unique primate evolutionary history on this island, and demonstrates extreme phylogenetic diversity unparalleled by any other place on earth (Sechrest et al., 2002). Moreover, more than 67% (43/64) of extant lemur taxa face a significant risk of extinction over the next several decades. In terms of total number and percentage, there are more threatened primates in Madagascar than in any other country (Mitterrmeier et al., 2003). Finally, the phrase �risk of extinction� carries a chilling reality in Madagascar, unlike other nations, where 17 or more primate species (in 9 or more genera!) actually have gone extinct within the last 2000 years. Such extinctions are generally attributed to the first arrival of humans to the island about 2000 years ago (Godfrey & Jungers, 2003).

The silky sifaka (Propithecus candidus, above) is a critically endangered indrid lemur living within the fragile borders of just two protected areas (Marojejy National Park: <www.marojejy.com> and Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve) in the small mountains of northeastern Madagascar. With only an estimated 100 to 1000 individuals remaining in the wild (there are none in captivity), silky sifakas are one of the three rarest lemurs in all of Madagascar and are one of the Top 25 most endangered primates in the world, out of over 600 total primate taxa (Mittermeier et al., 2002). Silky sifaka conservation is threatened by human hunting (Safford & Duckworth, 1989; World Wildlife Fund staff at Andapa, Madagascar, personal communication, 2001, 2003; K. Keiser, personal communication, 2001), hunting by the fossa, a mammalian carnivore (personal observation, 2001; Wright, 1998), and habitat loss from almost annual cyclone damage (Wright, 1999) and slash and burn agriculture (Goodman, 2000).

Human Hunting of Lemurs

Figure 2: Slaughtered lemurs.

Historically, as for other lemurs, the greatest conservation threat to the silky sifaka has been cultivation of hill rice through slash-and-burn agriculture or �tavy� (Mittermeier et al., 1994). Although human hunting of primates in Madagascar is generally less widespread than in Africa or Asia (Cowlishaw & Dunbar, 2000), nevertheless in some parts of Madagascar, such as Marojejy National Park, steady lemur poaching is evident. Tattersall (1982) suggested hunting must be occurring, given that the most accessible parts of Marojejy seemed �largely bereft of larger mammals and birds�. Duckworth et al. (1995) found numerous lemur traps and �villagers said that lemur hunting is their main reason for penetrating the reserve� (p.556). More recently, Goodman (2000) identified many human trails utilized by local people during lemur hunting, to gain access to hidden agriculture, and to harvest forest plants for medicinal and construction purposes. In 2000, a silky sifaka was killed by a poacher, but confiscated by local authorities (see photo). Similarly, during the 14.5 months of my research from 2001 to 2003, several episodes of lemur poaching within �protected areas� were evident. Estimated lemurs killed per hunt ranged from several to 70, with each being sold for 25,000 FMG (US$4) on average.

Unfortunately, there is no fady or taboo against hunting of the silky sifaka as there is against hunting of Indri, the largest extant lemur. Nor is there a shortage of meat in this cattle and rice culture situated within the wealthy vanilla-growing region of Madagascar. After questioning numerous local villagers and authorities as to the reason for lemur hunting, it became clear that upper middle class families enjoyed the taste of wild lemur as a delicacy or �picnic food�. Several individuals remarked that the meat tastes so good, one does not even need sakai or Malagasy hot sauce. Several individuals testified that the upper middle class hire local impoverished men and provide them with guns and bullets for the lemur hunt. It also became clear that many people living near these protected areas do not understand how rare and special these lemurs are. I therefore began a conservation education program in collaboration with local authorities, the Peace Corps, and Cornell University, with the support of the Conservation Committee of the American Society of Primatologists.

Although conservation education programs near or within protected areas in developing nations are relatively recent (Jacobson & Padua, 1995), such efforts are an increasingly routine goal of wildlife researchers. Although very few doubt the importance of such endeavors, some question whether quantitative evidence exists as to their effectiveness (e.g. Cowlishaw & Dunbar, 2000). There have been some well-documented successes. Blanchard (1995), for example, demonstrates dramatic population size increases (doubling in some cases) in Canadian seabirds following an intensive decade of local environmental education. Significant changes towards pro-conservation attitudes and increases in animal recognition by local peoples have been documented in mountain gorillas (Weber, 1995) and golden-lion tamarins (Dietz & Nagagata, 1995) following educational programs.

Conservation Education: Appeal to Hearts and Minds

A two-pronged strategy towards conservation education about the silky sifaka was adopted. The first component might be considered the �cognitive� component while the second can be labeled the �emotional� component.

The goal of the first component was to increase awareness and knowledge in local villagers and children about the uniqueness of, and existing threats toward, silky sifakas. This goal was pursued through:

The goal of the second �emotional� component was to associate conservation of the silky sifaka with positive emotional experiences. In other words, we hoped to appeal to their hearts as well as their minds. Traynor (1995) points out that �increased knowledge about the environment does not automatically result in behavior that is environmentally responsible. Affective and social factors must also be addressed since people�s behavior depends not only on their skills and knowledge but also on their feelings, motivation, and commitment� (p.17-18).

Towards this end, a wildlife art contest was conducted with local children following a several-hour discussion of biodiversity, endemism, and ecotourism. Throughout this time there was an interactive discussion of current local environmental threats. All interested children were provided with colored pencils and paper. It was our hope that this artwork could ultimately be sold to ecotourists visiting the park since there are presently no local crafts for sale at the park entrance. Children that showed the most interest or effort in their artwork and/or during the interactive discussion were invited in groups (average size, 14 kids) for free 3-day trips into Marojejy National Park to observe and learn about the silky sifakas.

Four groups, totaling 55 children, were brought into the park. These trips took place between June and August, 2004. All of these children live adjacent to the park but had never been within the park boundaries. They were all extremely excited and very happy to make the trip. While hiking to camp we played a species identification game, where all known plant and animal species were called out as they were encountered. We took turns telling the group about our favorite animal or plant and why we liked it so much. While in camp, we read a conservation story book about a Malagasy hunter who is slowly convinced by his ancestors and the creatures of the forest, who speak to him in his dreams, to respect nature as that is the wish of the ancestors. Then all the children acted it out as a skit. We discussed the behavior and conservation threats to silky sifakas. Then we asked the children to make up songs about what they learned and we all sang those songs. At dawn we tracked and observed the group of silky sifakas that were the subject of my research.

Silky sifakas are absolutely stunning, gorgeous animals with creamy white pelage that has inspired their nickname, �Angels of the Forest�. Virtually all observers, particularly the children, appeared awe-stricken, lost in wonder and joy at their first live sighting of this special lemur. All children returned home with silky sifaka flags and other conservation-related mementos.

Lessons Learned: Village School Presentations

The participation of local teachers greatly facilitated the effectiveness of the school presentations. We actively recruited their assistance, which not only made the teacher feel more involved with what we were doing but also ensured a far more orderly classroom. A slide projector designed for use in developing countries worked very well. It has few moveable parts, projects only one slide at a time, and is powered by a rechargeable battery that can be charged using either solar panels or traditional wall outlets. A teacher recommended we use a battery-powered megaphone to maintain the attention of large groups of children. This was valuable advice. Not only did use of the megaphone permit more people to hear what was being said, it also instantly quieted down the crowd. Although in some cases we spoke to groups as large as 200, in the end we felt that more learning took place in groups of 75 or less. Whenever possible, we divided classes to reduce the group size. Questions were encouraged at all times. We asked the children for their help in saving the silky sifaka. We asked them for advice and ideas. Nearly every student who asked a question or responded to one received an informational photo. The participation of local teachers helped the children to overcome politeness and fear and ask a question.

All presentations were given in the local dialect of the Malagasy language, unless the teacher requested we speak in French. During the presentations, we changed speakers several times to maintain student attention and interest. Typically I began with basic slides about silky sifaka location, rarity, and behavioral biology. After 15 minutes or so, Rabary Desire, a gifted speaker, local environmentalist, and teacher would step in and ask more personal questions of the students, such as �Have you ever seen this animal? Why should we protect this animal? What do you think the threats are to this animal?� Desire would then go on and speak about the next batch of slides covering threats to these animals. Finally after 30 minutes, just as the students were losing interest, Nestor, our most vibrant speaker, would take the stage.

Nestor is a forest guide who tracked and followed wild silky sifakas with me for 14.5 months. He was originally a local farmer and can speak to the students more as an average local man. He spoke emotionally and passionately from the heart about how he used to be a hunter, and now after learning so much about these animals, all he wants to do is protect them and learn about them. Nestor described what an average day is like in the forest. He shared several funny tales of his work tracking the silky sifakas, such as the time one of my field research assistants was afflicted with a leech sucking on her eyeball, and the time I developed an abscess from a poisonous insect bite that became larger than a white man�s fist. He acted it out so well as he spoke. He returned to silky sifaka behavior and acted out an adult female cuffing a male, and showed how the silky sifakas played with one another and showed clear sleeping partner preferences. The students absolutely loved it, and wanted to hear more. Towards the end, he became very serious and described how the silky sifakas appeared in his dreams and that is why he respects them so much and how he tracked them with such ease. The students too become very quiet with serious looks on their faces. Dreams are taken very seriously in Malagasy culture; some believe that is how ancestors communicate with the living. The teacher nodded that the time was up and invariably we were followed by huge groups of children as we left. They had so many questions. We stayed for a long time afterwards and sat with them and talked and laughed. When we finally left, they begged us to return and we could only say �We hope so, but you are the ones who can make the difference.�

Lessons Learned: Ecotours with Local Children

The Malagasy conservation literature we had with us frequently provided some activities of interest to the students. When discussing this literature we did not read in a formal, rigid manner � rather we kept things open and tuned to the students� interests. If they started acting parts out, we proposed a skit. If they started singing, we all made up songs and shared them with the group. Despite this flexibility, we had a specific curriculum that we wanted the students to learn. At the end of each night in the forest we would review exactly what we had learned about the silky sifaka and conservation threats. We were pleasantly surprised how eager the children were to learn these facts once they had seen the animal in the wild.

However not all of our games and literature were a success. In particular, a conservation-oriented Malagasy language crossword puzzle was generally not understood or of interest to the students. It was like nothing they had ever seen before and perhaps too formally academic.

Finally, deciding which students would be permitted to attend these forest trips was extremely challenging. The initial art contest and question-and-answer session proved effective in identifying many interested students; however there were still far too many students than we were able to bring. We finally asked local teachers to choose the best or most deserving students among those remaining.

Conclusions

Overall, we found all teachers and students to be very interested in the silky sifaka and genuinely concerned about its plight. As is often the case (Weber, personal communication), people were most curious about the behavior of these lemurs. The donated informational photos, field guides, and maps were in great demand. We felt it was important to provide local people with conservation mementos they could take home, keep for a long time, and show to their friends. In all cases, it proved crucial to visit the schools in advance and schedule presentations with the permission and assistance of school officials. It was not difficult to make radio announcements of upcoming presentations or set up radio interviews. Again, we found that the radio stations were eager to interview us and provide information to their audiences. After this experience, it seems clear that local conservation education can have a great positive impact on the conservation of the silky sifaka.

References

Blanchard, K. A. (1995). Reversing population declines in seabirds on the North Shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Canada. In S. K. Jacobson (Ed.), Conserving wildlife: International education and communication approaches (pp. 51-63). New York: Columbia University Press.

Cowlishaw, G., & Dunbar, R. (2000). Primate conservation biology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dietz, L. A.; & Nagagata, E. Y. (1995). Golden lion tamarin conservation program: A community educational effort for forest conservation in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. In S. K. Jacobson (Ed.), Conserving wildlife: International education and communication approaches (pp. 64-86). New York: Columbia University Press.

Duckworth, J. W., Evans, M. I., Hawkins, A. F. A., Safford, R. J., & Wilkinson, R. J.. (1995). The lemurs of Marojejy strict nature reserve, Madagascar: A status overview with notes on ecology and threats. International Journal of Primatology, 16, 545-559.

Godfrey, L. R., & Jungers, W. L. (2003). Subfossil lemurs. In S. M. Goodman & J. P. Benstead (Eds.), The natural history of Madagascar (pp. 1247-1252). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Goodman, S. M. (2000). Description of the Parc National de Marojejy, Madagascar, and the 1996 Biological Inventory of the Reserve. Fieldiana Zoology 97, 1-18.

Jacobson, S. K., & Padua, S. M. (1995). Conservation education using parks in Malaysia and Brazil. In S. K. Jacobson (Ed.), Conserving wildlife: International education and communication approaches (pp. 1-15). New York: Columbia University Press.

Mittermeier, R. A., Tattersal, I., Konstant, W. R., Meyers, D. M., & Mast, R. B. (1994). Lemurs of Madagascar. Washington, DC: Conservation International.

Mittermeier, R. A., Konstant, W. R., & Rylands, A. B. (2003). Lemur conservation. In S. M. Goodman & J. P. Benstead (Eds.), The natural history of Madagascar (pp. 1538-1543). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mittermeier, R. A., Konstant, W. R., Rylands, A. B., Ganzhorn, J., Oates, J. F., Butynski, T. M., Nadler, T., Supriatna, J., Padua, C. V., & Rambaldi, D. (2002). Primates in peril: The world�s top 25 most endangered primates. Washington, DC: Conservation International/IUCN: 1-22.

Safford, R., & Duckworth, W. (1990). A wildlife survey of Marojejy nature reserve, Madagascar. Report of the Cambridge Madagascar rainforest expedition. Cambridge: International Council for Bird Preservation Report #40.

Sechrest, W. (2002). Hotspots and the conservation of evolutionary history. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 99, 2067-2071.

Tattersall, I. (1982). The primates of Madagascar. New York: Columbia University Press.

Traynor, S. (1995). Appealing to the heart as well as the head: Outback Australia�s Junior Ranger Program. In S. K. Jacobson (Ed.), Conserving wildlife: International education and communication approaches (pp. 16-27). New York: Columbia University Press.

Weber, W. (1995). Monitoring awareness and attitude in conservation education: The mountain gorilla project in Rwanda. In S. K. Jacobson (Ed.), Conserving wildlife: International education and communication approaches (pp. 22-48). New York: Columbia University Press.

Wright, P. C. (1999). Lemur traits and Madagascar ecology: Coping with an island environment. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 42, 31-72.

Wright, P. C., Heckscher, S. K., & Dunham, A. E. (1997). Predation on Milne-Edward�s sifaka (Propithecus diadema edwardsi) by the fossa (Cryptoprocta ferox) in the rain forest of southeastern Madagascar. Folia Primatologica, 68, 34-43.

* * *

Agonism and Affiliation: Adult Male Sexual Strategies Across One Mating Period in Three Groups of Long-Tailed Macaques (Macaca fascicularis)

James E. Loudon, Agust�n Fuentes, and Ashley R. Welch

University of Colorado�Boulder and University of Notre Dame

Introduction

In primate groups whose members adhere to a clear social dominance hierarchy, high-ranking animals should have increased access to contested resources (Fedigan, 1983). Due to physiological differences between the sexes, theoretically, females and males place importance on different resources (Trivers, 1972). Female primates have a high energetic investment in prenatal and post-conception care, requiring access to a stable, high quality food supply, in order to provide vital nourishment for themselves and their offspring. In contrast, males are limited by access to females. In most cercopthecines, males have a minimal investment in their offspring and do not engage in parental caretaking behaviors. However, adult males may engage in defense against predators, group defense, or infant defense, which can be a potentially costly investment (Kappeler, 2000). Priority-of-access models (Fedigan, 1983) suggest that females of high rank should obtain increased access to nutritious food supplies, and high-ranking males should achieve increased reproductive success via increased mating opportunities.

In primate groups with overt male-male competition, high-ranking males usually win contests for access to feeding sites and fertilizations. However, high-ranking males may not be able to monopolize mating and reproductive success. This inability affords low-ranking males, subadult males, and extra-group males to employ strategies to obtain fertilizations outside of dominance contests. These strategies include sneak copulations and/or consortships (Sprague, 1992), queue jumping (Alberts et al., 2003), persistent following and/or shadowing of receptive females, sexual coercion (Smuts & Smuts, 1993), and using infants to gain favor with females (Itani, 1959; Deag & Crook, 1971; Strum, 1987; Ogawa, 1995a).

Smuts & Smuts (1993) proposed the �Sexual Coercion Hypothesis�, predicting that male aggression toward females or the threat of male aggression toward females may be a male tactic to increase the chances that the targeted female(s) will mate with the aggressive male, and not with other males (which might bring more aggression) during peak fertility. In contrast to an aggressive strategy, macaques may utilize infants to gain favor with adult females. Barbary and Tibetan macaques develop close bonds with infants and use infants in triadic interactions with other males (Deag & Crook, 1971; Ogawa, 1995a). Male-infant interactions were initially interpreted as a form of parental investment. However, across the Order Primates, several species engage in male-infant interactions and researchers have posited several hypotheses to explain this behavior. These include protecting the infant from infanticidal males (van Schaik et al., 2000), agonistic buffering (Deag & Crook, 1971), passports into groups (Itani, 1959), and kin selection.

Long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) live in large, permanent bisexual social groups with female philopatry and male dispersal (van Noordwijk & van Schaik, 2001). Alpha and beta M. fascicularis males generally have increased mating success and subsequently sire more offspring (de Ruiter et al., 1994). However high-ranking males cannot completely monopolize fertilizations, and this inability allows low-ranking males, subadult males, and extra-group males to obtain fertilizations by utilizing alternative strategies. Regardless of the strategy a male uses, the impact of female mate choice cannot be understated (Small, 1989). In long-tailed macaque groups, sexually active adult females may mate with all adult males in the group (van Noordwijk, 1985). Thus, high-ranking long-tailed macaque males can employ two strategies: copulating mostly with a high-ranking female, or copulating with many females (van Noordwijk, 1985).

The goal of this study was to determine whether adult males increase their reproductive success (measured by mating success) by utilizing an aggression-based behavioral strategy (e.g. sexual coercion), an affiliative-based behavioral strategy (e.g. affiliative interactions with infants), or both strategies.

Methods

Data were collected on three groups of long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) inhabiting the Padangtegal Temple forest site in Bali, Indonesia. The 139 macaques at this site have a total home range of ~24 hectares. See Fuentes and Gamerl (2005) for site description.

We used continuous focal animal follows and ad libitum notes to record the behavior of ten adult males (Altmann, 1974). The duration of each focal follow was 30 minutes. We collected 42 follows for 9 of the 10 adult males (21 hours per male). The remaining adult male, M7, died during the sixth week of the study; previously we had collected 38 focal follows (19 hours) on this individual. In total, we collected of 208 hours of data on all males (see Table 1). Each male was followed at various times of the day throughout the study. Individuals were identified by facial and body scars or irregularities and from pictures of each adult animal from previous field studies at the site. Research since 1998 at the site has produced a photographic catalogue and video library of every adult male and most of the adult females. Prior to the study we collected preliminary data, developed an ethogram, and conducted inter-observer follows (Cohen�s Kappa Calculation). The frequency and duration of each male�s behavior was analyzed on the SPSS 11.5 statistical package. We used a one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test to determine significant differences between the frequency and duration of aggression or affiliation directed toward adult females and/or infants, and the frequency of copulations at the population level. Due to small sample sizes, we used a Chi-Square Goodness-of-fit test with a Bonferroni post hoc test to determine significant differences among these variables between individuals in same group. We used a Spearman�s rho test to determine if the frequencies of copulations were correlated with aggressive or affiliative behaviors initiated toward females and/or infants. We report only the significant values hereafter.

Results

Inclusive Analyses/Within-Group Comparisons For Each Group: Between the two adult males in Group 1, we found significant differences in the duration of aggression initiated toward females (X2=14.1, p<0.001) and infants (X2=18.54, p<0.001), the frequency (X2=15.01, p<0.001) and duration (X2=2972.7, p<0.001) of affiliative behavior initiated toward females, and the frequency (X2=14.4, p<0.001) of affiliative behavior with females and infants. For Group 2 significant differences emerged between the four males in the frequency of copulations (X2=68.7, p<0.001), frequency of aggression initiated toward females (X2=48.5, p<0.001), duration of aggression initiated toward females (X2=488.9, p<0.001), duration of affiliative infant interactions (X2=420.8, p<0.001), total frequency of initiated aggression (X2=52.4, p<0.001), and the total frequency of affiliative interactions (X2=57.6, p<0.001). The three adult males in Group 3 exhibited significant differences in the frequency of affiliative interactions with infants (X2=49.7, p<0.001), duration of aggression initiated toward females (X2=17.7, p<0.001), duration of affiliative infant interactions (X2=5344.2, p<0.001), and total affiliative interactions (X2=17.7, p<0.001).

Between-Group Comparisons and All Adult Males in This Population: We found no significant differences in frequency and duration of these behaviors between groups. The frequency of copulations was not correlated with the frequency or duration of aggression or affiliative behavior initiated toward adult females or infants.

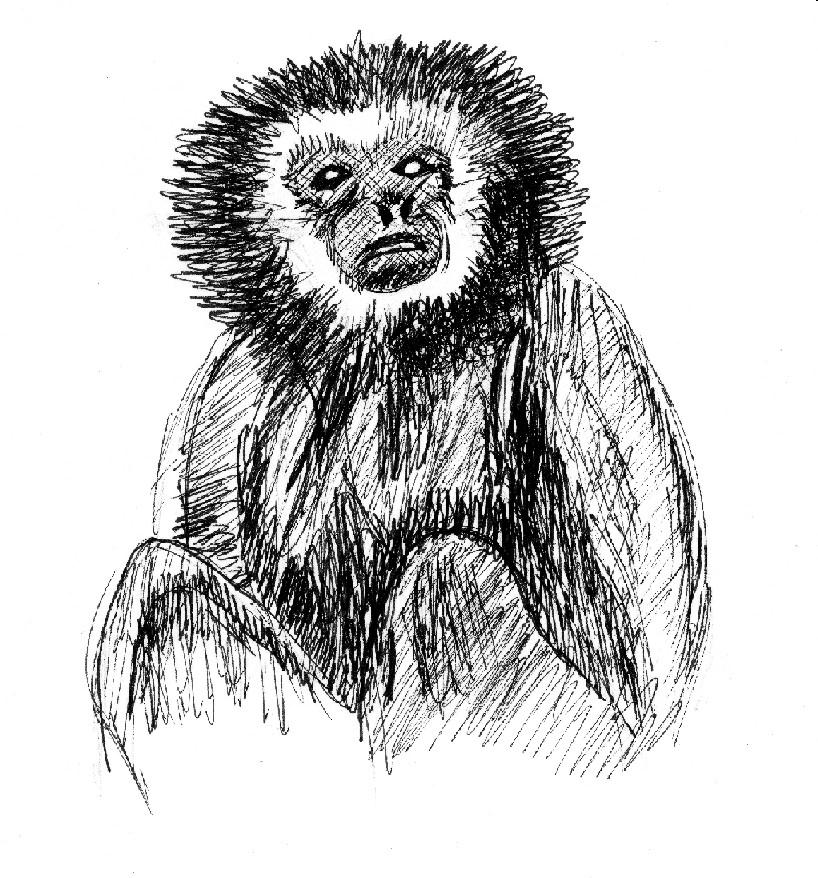

Discussion

Do females prefer aggressive males? Each adult male initiated aggression towards adult females, and in Group 2 and Group 3, the individual males differed in the duration of aggression they directed towards females. However, this variation in aggression across the males did not result in concomitant differences in copulatory frequencies. Copulation frequencies may not reflect rates of fertilization and our data could not clearly determine if this aggression coerced females to mate with the aggressive male at specific times. In each group the frequency of initiated aggression toward females surpassed the frequency of affiliative infant interactions (see Figure 1). On three occasions, the alpha male from Group 1 (M1), copulated immediately after attacking adult females. In these isolated events, intent on the part of the adult female is unknown and therefore it is impossible to determine if the female preferred an aggressive male due to behavioral cues or was acting out of fear of aggression and attempting to minimize potential injury. Group 1 had two adult males, one of whom was very old and died (M7) during the research period. It may be that the high-ranking male in Group 1 was able to sexually coerce females, because the females in this group could not enlist the help of the old, sick male. In Group 2, the alpha male (M17), was observed directing the most aggression toward adult females and had the highest copulation count. These results suggest that in Group 1 and Group 2, sexual coercion techniques afford high-ranking males higher mating success. Interestingly, in Group 3, the third ranking adult male (M9) obtained the highest copulatory frequency for that group (and the third highest for the population) and frequently directed aggression at adult females. While every male in this population initiated aggression toward females, this aggression did not correlate with copulations.

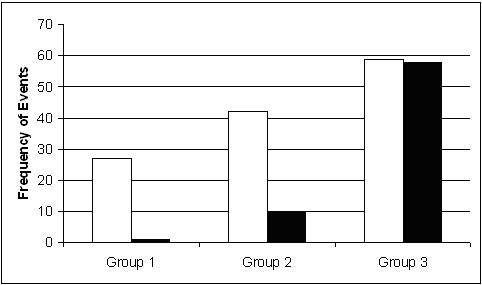

Figure 1: Frequency of aggression and affiliation with adult females. White bar = aggression; black bar = affiliation. Male-Infant Interactions: Male-infant interactions did not have a statistically significant relationship with the frequencies of copulations. However, 84% of the male-infant interactions occurred in Group 3. In comparison to Group 1 and Group 2 males, the duration of adult male-infant interactions in Group 3 was 11.7 times higher (Figure 2). Interestingly, during the study period, Group 3 exhibited frequent and high intensity fighting among the adult males and the dominance relations in this group were extremely unstable. The two highest-ranking males (M5 and M11) formed an alliance against a third adult male (M9), and directed high rates of aggression toward him. We observed M5 and M11 holding, carrying, and grooming infants at much higher rates than the other remaining 8 adult males in the population (18 and 35 occurrences respectively, compared to an average of 1.4 for the remaining males).

Figure 2: Duration of aggression and affiliation with infants. White bar = aggression; black bar = affiliation.

The adult males in Group 3 may be using infants to achieve access or support from adult females (passports and bridging) and also using infants to reduce levels of aggression from others (agonistic buffering) (Itani, 1959; Deag & Crook, 1971; Ogawa, 1995b). We recognize that low-ranking and subordinate males use infants as �agonistic buffers� to reduce aggression from dominant males. However in Group 3, the reverse was observed. Prior to the study period, M9 had reached full maturity, was in prime physical condition, and was larger than the high-ranking males. M9 occasionally displaced and chased the alpha and beta males if those males were alone. In this unusual situation, the higher-ranking males may have used infants to gain the association of females against the subordinate, but larger and aggressive young adult male.

Long-tailed macaques have demonstrated an ability to identify mother-infant pairs (Dasser, 1988). This ability, perhaps, allows adult males to use infants to their advantage by creating and maintaining relationships with others for the purpose of negotiating conflicts. Although our results do not fully support the �bridging� hypotheses, the highest-ranking males (M5 and M11) in Group 3 devoted little time in aggressive interactions and subsequently engaged in very high levels of male-infant interactions (frequencies and durations). Males in this group may be actively using infants to establish or reinforce bonds with females.

Conclusion

The alpha position was linked to the highest frequency of copulations in Groups 1 and 2. In free-ranging Sumatran long-tailed macaques, van Noordwijk & van Schaik (2001) note that males� lifetime reproductive success is largely determined by acquiring and maintaining dominance. Paternity tests demonstrated that alpha and beta males sire the highest number of offspring in long-tailed macaques (de Ruiter et al., 1994). However, these results may derive from female choice and/or a high-ranking male�s timing of copulation, as opposed to absolute copulatory frequencies (i.e. mating success). High-ranking males in Group 3 did not achieve increased copulatory success. The third ranking male, M9, obtained the highest frequency of copulations in this group. M9�s copulatory success may be attributed to queue jumping (Alberts et al., 2003), female choice (Small, 1989), or the high-ranking males� inability to monopolize access to females.

The results of our data collection did not fully support (i.e. statistically support) either of the two hypotheses, sexual coercion or the use of infants to increase access to females in order to gain copulatory success. Males at this site were observed engaging in affiliative behaviors with adult females and infants, and also behaved aggressively towards adult females. Rather than suggesting that coercive or affiliative strategies are not being practiced, our results may simply reflect the males� ability to use the most appropriate behavioral strategy at a specific time. If the results of this study are viewed as a �snapshot� in each male�s life history, we may have observed one or multiple behavioral strategies, which were not mutually exclusive and were useful for this mating season and appropriate for the social atmosphere of each group.

References

Alberts, S. C., Watts, H. E., & Altmann, J. (2003). Queuing and queue-jumping: Long-term patterns of reproductive skew in male savannah baboons, Papio cynocephalus. Animal Behaviour, 65, 821-824.

Altmann, J. (1974). Observational study of behavior: Sampling methods. Behaviour, 49, 227-266.

Dasser, V. (1988). A social concept in Java monkeys. Animal Behaviour, 36, 225-230.

Deag, J. M., & Crook, J. H. (1971). Social behavior and �agonistic buffering� in the Barbary macaque, Macaca sylvanus L. Folia Primatologica, 15, 183-200.

Fedigan, L. M. (1983). Dominance and reproductive success in primates. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 26, 91-129.

Fuentes, A., & Gamerl, S. (2005). Disproportionate participation by ages/sex class in aggressive interactions between long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) and human tourists at Padangtegal Monkey Forest, Bali, Indonesia. American Journal of Primatology, 66, 197-204.

Itani, J. (1959). Parental care in the wild Japanese monkey, Macaca fuscata fuscata. Primates, 2, 61-93.

Kappeler, P. M. (2000). Primate males: Causes and consequences of variation in group composition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ogawa, H. (1995a). Recognition of social relationships in bridging behavior among Tibetan macaques (Macaca thibetana). American Journal of Primatology, 35, 305-310.

Ogawa, H. (1995b). Triadic male-female-infant relationships and bridging behaviour among Tibetan macaques (Macaca thibetana). Folia Primatologica, 64, 153-157.

de Ruiter, J. R., van Hoof, J. A. R. A. M., & Wolfgang, S. (1994). Social and genetic aspects of paternity in wild long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis). Behaviour, 129, 203-224.

Small, M. F. (1989). Female choice in nonhuman primates. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology, 32, 103-127.

Smuts, B. B., & Smuts, R. W. (1993). Male aggression and sexual coercion of females in nonhuman primates and other mammals: Evidence and theoretical implications. Advances in the Study of Behavior, 22, 1-63.

Sprague, D. S. (1992). Life history of male intertroop mobility among Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata). International Journal of Primatology, 13, 437-454.

Strum, S. C. (1987). Almost human: A journey into the world of baboons. New York: Random House.

Trivers, R. L. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. In B. Campbell (Ed.), Sexual selection and the descent of man, 1871-1971 (pp. 136-179). Chicago: Aldine Press.

van Noordwijk, M. A. (1985). Sexual behavior of Sumatran long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis). Zeitschrift f�r Tierpsychologie, 70, 277-296.

van Noordwijk, M. A., & van Schaik, C. P. (2001). Career moves: Transfer and rank challenge decisions by male long-tailed macaques. Behaviour, 138, 359-395.

van Schaik, C. P., Hodges, J. K., & Nunn, C. L. (2000). Paternity confusion and the ovarian cycles of female primates. In C. P. van Schiak & C. Janson (Eds.), Infanticide by males and its implications (pp. 361-387). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

* * *

Travelers� Health Notes: International Assn for Medical Assistance to Travelers

The International Association for Medical Assistance to Travelers (IAMAT), a volunteer group, compiles an annual list of doctors around the world who meet the organization�s criteria, who speak English or another second language, and who agree to charge a specific fee. The 2005 Directory lists the current schedule of fees as US$80 for an office visit, US$100 for a house (or hotel) call, and US$120 for night, Sunday, and local holiday calls. These fees do not include consultants, laboratory procedures, hospitalization, or other expenses. The current listing of doctors and centers includes 95 countries.

IAMAT also publishes and provides to its members pamphlets on immunization, schistosomiasis, and malaria, as well as �World Climate Charts� and a �Traveller Clinical Record� form. IAMAT has a scholarship program for physicians from developing countries to attend travel medicine training courses in North America.

For information, contact IAMAT, 40 Regal Rd, Guelph, Ontario, N1K 1B5, Canada [519-836-0102]; 1623 Military Rd, #279, Niagara Falls, NY 14304-1745, U.S.A. [716-754-4883]; 206 Papanui Rd, Christchurch 5, New Zealand; or 57 Voirets, 1212 Grand-Lancy-Geneva, Switzerland [e-mail: [email protected]]; or see <www.iamat.org>.

* * *

Primates de las Am�ricas...La P�gina

Estimados lectores, este n�mero contiene informaci�n sobre dos congresos primatol�gicos, as� como informa-ci�n de revistas primatol�gicas latinoamericanas que esperamos sean de utilidad. Saludos, Tania Urquiza-Haas <[email protected]> y Bernardo Urbani <[email protected]>.

I Congreso de Asociaci�n Colombiana de Primatolog�a

Este congreso se llevar� a cabo en la ciudad de Santaf� de Bogot�, Colombia. Las fechas confirmadas son del 2 al 4 de noviembre de 2005. Los t�picos principales incluyen: Conservaci�n y manejo in situ y ex situ, biolog�a y ecolog�a adem�s de medicina. Para m�s informaci�n escriba a <[email protected]> o visite <www.geocities.com/primatologica/#>.

VI Congreso de Asociaci�n Primatol�gica Espa�ola

Esta reuni�n ser� entre 27 y 30 de septiembre de 2005, en la Facultad de Psicolog�a de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Espa�a. Entre los temas del congreso se encuentran uso de herramientas, etolog�a infantil y diferencias y similitudes entre humanos y simios. Para mayor informaci�n contacte al Dr. Fernando Colmenares o la Dra. Mar�a Victoria Hern�ndez-Lloreda por los correos electr�nicos <[email protected]> y <[email protected]>. Tambi�n puede visitar <www.ucm.es/info/ape05>.

Bolet�n Primatol�gico Latinoamericano en la red

Algunos art�culos del cl�sico Bolet�n Primatol�gico Latinoamericano se encuentran en l�nea y formato PDF en la p�gina de la Estaci�n Biol�gica de Corrientes, Argentina <ar.geocities.com/yacarehu/revista.htm>. Entre ellos se encuntran:

El primer n�mero de la revista digital trimestral de la Asociaci�n Colombiana de Primatolog�a est� ya en Internet bajo la direcci�n editorial de Mauricio Garc�a Arcila, Mar�a Ortiz y N�stor Varela. Dicha publicaci�n se puede bajar en la p�gina de la asociaci�n <www.geocities.com/primatologica/#> o recibir suscribi�ndose al <[email protected]>. El primer n�mero (2004, Vol. 1, Nro. 1) contiene los siguientes art�culos:

* * *

Southeast Asian Primatological Association Established

After a series of deliberations beginning in Torino, Italy, then in Bangkok, Thailand, and finally in Jakarta, Indonesia, the Southeast Asian Primatological Association (SEAPA) was formally launched on April 4, 2005, during the first Southeast Asian Congress of Primatology, held at the Ragunan Zoo�s Schmutzer Primate Center in Jakarta, April 3-7. The Congress was concurrently organized with the Congress of the Indonesian Primatology Association (APAPI) and jointly hosted by SEAPA and APAPI. Over a hundred Indonesian primatologists and invited representatives from the other ASEAN member countries attended the congresses.

SEAPA, whose mission is �To promote and enhance the scientific knowledge and the conservation of primates in the ASEAN Member Countries (AMCs), particularly in their natural habitats,� has four main goals:

Membership in SEAPA is open to any individual engaged in the pursuit of scientific knowledge and the conservation of primates in the AMCs, or interested in supporting the goals of SEAPA. There are two categories of memberships:

* * *

Electronic Freedom of Information Act: Availability of Annual Reports

APHIS Animal Care has announced that as of Tuesday, May 10, annual reports submitted by registered research facilities will be available on the APHIS Website, <www.aphis.usda.gov/ac/redacted_inspections /WebList.htm>. The full contents of the reports will be available, although all confidential information will be redacted. NABR encourages its members to check the site regularly for reports on their institutions. NABR also strongly encourages all member organizations to request a copy of their report so that each institution knows exactly what the general public will be seeing.

* * *

Meeting Announcements

The Laboratory Animal Welfare Training Exchange, which aims to promote an information exchange among laboratory animal welfare trainers on training programs, systems, materials, and services for the purpose of promoting the highest standards of laboratory animal care and use, will hold its 2005 Conference August 17-19, in San Diego, California. Charles River Foundation is sponsoring a Poster Session, giving away cash prizes ($1,000 total) for the best posters. For information and registration materials, see <www.lawte.org>.

ESLAV (European Society of Laboratory Animal Veterinarians) and SECAL (Spanish Society for Laboratory Animal Science) are organizing a Joint Meeting entitled �Welfare in Facilities� . This will be the 6th and 8th Scientific Meetings, respectively, of these organizations and will be held in Elche, Alicante, Spain, on October 5-7, 2005. More information can be found on <www.secaleslavmeeting.org>.