For me, the changes occurring in the way anthropologists view place are not the result of a siege against the concept, but rather an extreme shift in place boundaries and accelerated changes in place-time. As several authors have noticed, the concepts of nation-states as "imagined" communities have transcended geographical and political boundaries in today's world. Thus, places have become amorphous, more tenuous, less containable. The more drastic change in place-making has been the increased mobilization of people and ideas, which has led to changes in "place-time" at a rapid pace. Anthropological places have always changed from one moment to the next, but technology and national interests bring about new conceptions of places, from archaeological sites to natural landscapes to local communities. Long gone are idealized places (or non-places) that remain in the "perpetual present" (Auge 105).

The challenge then, as anthropologists and archaeologists, is to be transparent about the "place" we're actually studying (which may, of course, change during the process!). We have to start somewhere: which landscape? (geographic region, community, "locality") which ethnoscape? ("imagined" community, group that shares cultural identity or practices) and which "taskscape"? (economic activity, domestic activity, ritual or symbolic activity). So even though place-making is changing, and the place-world is markedly different from one day to the next, we can embrace these processes in research design. This also includes finding a balance between the indigenous conceptions of place and the view of a place through the lens of anthropology.

(Random thought: Is "home" the basic unit of anthropological place?)

When and where were the first stairs? More importantly - are stairs a cultural universal? Practically, they could be a response to the physiological need of using energy efficiently by walking on flat, rather than sloped, surfaces. Functionally, they connect places at lower elevations to those at higher elevations. One could argue that they are based on movement from one plane to another. Stairs are also intimately linked with performance and other cultural practices. People decorate stairs with accessories or color, and even construct them out of precious materials. Stairs could represent a solution to a physiological problem as mentioned, or could even be mimicry of the natural world, which contains stairs of stone or soil. Perhaps even, stairs are the result of generations of experimentation with structural trial-and-error when constructing dwelling places.

The nature of a staircase gives revealing clues about its associated structures. Restrictions of movement and access determine who uses staircases at certain times. Stairs can therefore be constructed to establish social or order, whether to oppress or enable certain people. So when terracing or molding resembles stairs, is it imitation or did structural innovations come before stairs?

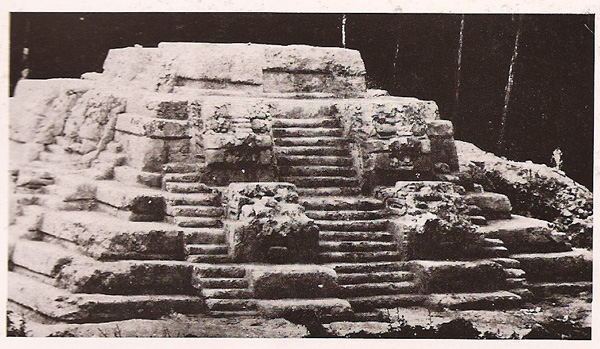

(Ricketson 1937, plate 33)

The building above is at the site of Uaxactun, as the main, western pyramid of the Group E (sub-VII). Very early, lowland Maya pyramids developed complex and multiple staircases flanked with masks, connecting different platforms. Over the semester I hope to investigate why people were breaking up "space" in a terraced, rectilinear way to make "place" in this time period.

Posted at Feb 08/2009 02:52PM:

omur: James, your idea of taskscapes I find very intriguing, and staircases, which you bring up in the second half of your commentary, is such a great example of a technology of place-making. Moving from the very basic human idea/bodily practice of moving from one platform to a higher one, monumentalization of the staircase is transforming not only the practice of ascending and descending, but morphs a transitory, interspatial space into a spectacle of space in its own accord. While our modern elevators make an abstraction of the spaces that they connect (Floor 1, Floor 2 etc), Maya Staircases embody monumentality and connectivity as a technology of connecting and raising. Georges Perec's Species of Spaces surely has a staircase chapter.