Blue State Cafe, Fri Feb 06/2009 12:55

Has locality lost its moorings? This seems to be the basic question that Auge (1995) and Appadurai (1996) ask in their essays on place and supermodernity. There, we are confronted with two major issues: one is the geneaology of place in anthropology and other fields of social sciences/humanities as constructed between the indigenous fantasies rooted in the landscape and the ethnographic imaginations of places through operations of academic objectification.

The second one concerns the peculiar set of spaces, referred as "non-places" by Auge, created by supermodernity and its contemporary practices of spatial production. These non-places are transitory places, where human actors pass through as anonymous individuals but do not relate/identify with in any intimate sense. Airport terminals, hospitals, movie theaters and shopping malls are great examples of such public spaces, where social action does not take place. They are desolate places where poetics of dwelling does not thrive. Residues from human practices do not accumulate (they are continuously wiped out by the state) and soil is inaccesible to the touch, non-places tend to be characterized by concrete and artificial surfaces. On entrance, your identity is checked, passport stamped, individuals permits issued, boarding passes printed, your bags must be kept with you at all times otherwise "security" will take them away. In hospitals, you are given plastic bracelets and galosh footwear, in museums your hand is stamped with ink, your body is marked. In non-places, you are only allowed to follow certain paths- your movement, gestures and bodily acts are under surveillance. The nature of these non-places fits well with the lifestyles of supermodernity, which has become increasingly obsessed with panoptic control and security, and characterized by impatience and acceleration of time.

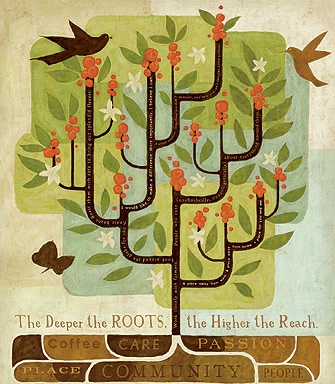

Non-places are then defined based on precisely as what place is not, by Auge, i.e. localities that come to existence by virtue of being relational, deeply historical and intimately connected to identity, both social and individual. It is where history erupts in the form of a site-specific event, landscape erupts as the loci of the intensified relationships between humans and the world. The problem here that Auge points out however is the anthropology's long-term disciplinary practice of producing a romantic vision of places, as timeless, unchanging, "rooted in the intact soil", kept up by archaic and exotic rituals of the indigenous. He also cleverly points out the "totality temptation" where culture is imagined as holistic and accurately represented by randomly selected individuals, artifacts, places and practices from within itself. This anthropological othering of its subject reminds me of the famous Starbucks posters, which locate the origin of their coffee at such unspoiled exotic places.

| The concept of place, as an exotic far-away locale, that is rooted with its "traditional" ethnographically interesting practices untouched by pollutions of modernity, forms the backbone ideology of these posters. According to structuralist anthropological accounts, these places are cultivated and defended by the essentially non-discursive practices of their indigenous dwellers, but also by the spirits of the place, maintained by the operation of chthonian and celestial powers of the landscape. Dealing with place and landscape in the postcolony requires a serious critique of such ethnographic illusions, and taking into account that places are deeply historical and have never been immune to challanges of larger networks of interaction. Ethnohistory then becomes a critical component of place research, essential to span the epistemological gap between archaeological explorations of landscape (distanced to the ancient past) and ethnographic research (located in the "here" and "now". This will finely prepare us to consider archaeological investigations of the spaces of industrial modernity, and ethnographic insights into the configuration of ancient landscapes. In this sense Appadurai's suggested goals are novel: to shift the history of ethnography from a history of neighborhoods to a history of technologies of the production of locality, and think through again the colonial intervention of academics, travellers, anthropologists, missionaries, linguists and tourists in the production of indigenous categories. Aren't the idea of fetish (Pietz 1985), or the idea of chiefdom (Pauketat 2007) the product of such interventions? Or rather confrontations, encounters or better: collaborations? |

This destabilization of anthropology and archaeology's relationship with its subjects, the status of place as an object of inquiry has to be reconsidered- as heterogenous and deeply politicized, contested and negotiated, fragile in its materiality, monumentalized to initiate state practices of appropriation, cleansing and collective forgetting. We should not consider places and non-places as absolute categories that exclude each other, but acknowledge the fact that even non-places have the potential to become places, as it was in the case of a Providence artist who took residence in the storage spaces of Providence Place Mall, poking a hole in the the non-place par excellence of our little town, turning a strictly controlled and surveyed space to his very home. Breakdown of an elevator, a transitory space that configures the building into abstract numbers, can turn it into a place of social interaction if the sixteen people trapped in it simply sit down and start to chat. Once a friend told me of a movi-theater showing of a 4 hour long Andy Warhol movie, where the audience broke into a heated conversation as the movie played on the screen. An abandoned railroad bridge is pulled into located, unorthodox performances of every life through graffiti-making and beer-drinking.

Is it possible to understand today's rising academic interest in places as anthropology's coming to terms with its past dis-place-ment of its object in time and space (Fabian 1983)? An archaeology of place that embraces the deep historicity, poetics and politics of places, and reenacts its stratigraphy of meanings including the genealogies of colonial, missionary discourse can well be a postcolonial gesture to reengage with the world in a novel way.

Bibliography

- Appadurai, Arjun; 1996. "The production of locality," Modernity at large: cultural dimensions of globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 178-199.

- Auge, Marc; 1995. Non-places : introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity. London, New York: Verso.

- Fabian, Johannes; 1983. Time and the other: how anthropology makes its object. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Pauketat, Timothy R.; 2007. Chiefdoms and Other Archaeological Delusions. Rowman Altamira.

- Pietz, William; 1985. “ The problem of the fetish” Res 9: 5-17.