I wanted to address Boivin's introduction about the non-functional aspects of what she termed the "mineral world." All across Mesoamerica, certain minerals and clays have been used in non-functional deposits (e.g. La Venta, Tab.; Naranjo, Guat.). Processing of pigment into paints is also a highly sophisticated craft among the Classic Maya. However, what I thought especially relevant to Boivin's point were the meaning behind, and animated qualities of stone among the Classic Maya and across Mesoamerica, namely obsidian and chert, or flint.

Flints, for the Classic Maya were important functional items as blades, whether for household use or for weaponry. In the absence of metalworking, chert blades served as the primary tool for many things, and finer obsidian blades served for more delicate tasks. Ample evidence exists (see David Stuart 2007, Dumbarton Oaks Symposium) that the Classic Maya valued things that were shiny and hard, as polished fetishes. Furthermore, much evidence exists that show that chert blades were considered alive, and this animate quality shows up in the form of eccentric cache blades.

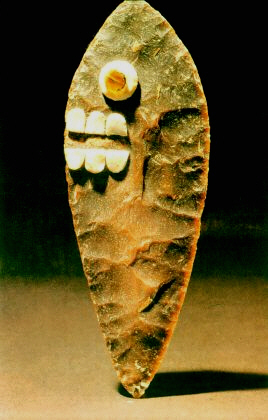

This image shows three heads in profile sprouting from a central blade, all three adorned with royal headdresses. Many of these are found in royal cache deposits across the Maya region. Although these exquisite sculptures would not have been used as actual weapons, they show the importance of such blades as having personalities or being connected with personhood.

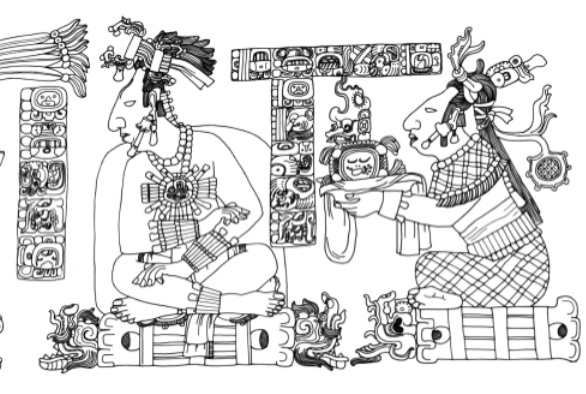

In this scene from Palenque, the ruler on the left receives his "flint and shield" from his mother on the right, as the symbol of power for warrior kings. The flint, with a face, is marked with dotted borders and shows a personified blade as a key element of kingship as well. In fact, flints with faces appear in Postclassic Aztec art as well, almost evoking that cuts from flints are symbolic "bites" from the mouth of the blade.

In a final, and probably the most poetic, example, flints also played a role in narrative storytelling among the Postclassic Mixtec of Oaxaca, Mex. In the following image from the Codex Selden, two characters are depicted in speech, shown by the scrolls emitting from their mouths.

The artist here creates an amazing metaphor for harsh words - "flinty speech" - as the speech scrolls themselves actually have blades that reach out towards the protagonist of the narrative. One final example of the importance of flint in Mesoamerica deserves mention. In the 20-day calendar that is shared across the Classic and Postclassic periods, one day is known as the day of the flint, and also many times as a year in Mixtec and Aztec daykeeping. This suggests that flint was important as a component of time itself, and also translated into the naming of individuals born on that day or year. Thus certain auspicious (or inauspicious) luck could come from being born in a "flinty" time.

Countless other examples from around Mesoamerica (and other parts of the world) support the claims that Boivin makes about the need to explore the other properties of the mineral world that sprung from cultural beliefs and practices. In relation to making places, it could have implications about rethinking quarries or other mineral resources while surveying. Boivin's argument also builds the case for considering the biographies of objects rather than just considering their utilitarian function.