By Alex Ruby

New Markets for a New America

In the summer of 1787, John Brown was by all accounts searching for a new market in which to leave his mercantile footprints. Independence from Britain had granted the fledgling United States free reign to trade with any part of the world, and this freedom, combined with an economic depression, pushed American entrepreneurs’ eagerness to find something new. One such market that had been off-limits to colonial America was the East Indies—here defined as India and China. Among others, John Brown saw this market as potentially very profitable, and his penchant for taking risks led him, in 1787, to be the first Rhode Islander to send a ship, the General Washington, in that direction (Hedges, Vol. 2, p.15-16).

The relatively rich collection of documents pertaining to the voyages of the General Washington provides a wonderful glimpse into the early development of American trade to the East Indies region. Such documents are all the more interesting due to the fact that trading in this region was so new to American merchants that, frankly, they knew very little of what to trade. While the historical record—primarily contained in the Brown Family Business Records collection at the John Carter Brown Library—gives us a number of examples of life on the General Washington as it sailed and traded in the East Indies, the largest number of documents pertain primarily to the business decisions taking place at home in Providence, especially just before and for some time after the actual voyage. These documents do much to reveal the decision-making process that went into opening American trade with India and China.

The First Voyage to China—December 27, 1787 to July 6, 1789

Preparing for Voyage

While John Brown first envisioned a voyage to China during the summer of 1787, it obviously took some time until his dream was realized. As with many trading ventures of the era, John Brown, who at this point in his career had departed from the company of his brothers (Nicholas Brown & Co.) and had instead partnered with his son-in-law, John Francis, to form the firm Brown & Francis, needed others to invest in his idea for it to come to pass. It was simply too risky and too expensive for one investment house to foot the bill of the entire operation, especially when entering a new market. Although Brown & Francis made the largest investment (a ½ share) in the voyage, John also recruited his brothers’ firm (now called Brown & Benson) as well as their partner Welcome Arnold to invest in a 1/8th and 1/24th share, respectively (Hedges, Vol. 2, p.16). On November 5, 1787, Brown & Benson laid out the details of their 1/8th share in a document, agreed to and signed by Brown & Francis, entitled “Mr. J Brown’s Proposal for us to purchase One eighth of ship General Washington”. They calculated their total investment up to this point to be £450. (Rhode Island used the Rhode Island pound, also called Rhode Island lawful money, until a few years after ratifying the Constitution in 1790.)

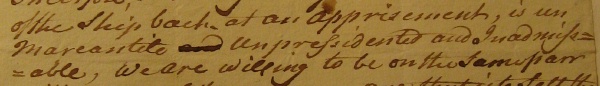

If from this successful agreement one gets the impression that everyone was gung-ho about sending a ship to China, one would fall far from the truth. Not only did Brown & Benson and Welcome Arnold take their time in agreeing to join Brown & Francis’ venture (Hedges, Vol. 2, p.15-16), but they even apparently had notions of pulling out their investment after making this agreement, which struck Brown & Francis, as revealed in a letter to the two parties, as “unmarcantile, unpressidented and Inadmissable.” That this letter was dated simply “Munday Morn’g 7. oClock” highlights a fact that despite the extensive paper record between these invested parties, they were rarely more than a few blocks apart. It is fun to read between the lines and imagine John Brown heckling his brothers to get their act together, and it is fortunate that despite the ever-present possibility of simply discussing these matters in person, both companies still decided to copiously record nearly all business decisions.

The three investors bickered frequently both before and after the first voyage to China, but when it came to their united interest in a successful venture, they also had moments of clearly coming together. Gathering all of the supplies necessary to load onto the ship was not simply a matter of coordinating between investors, but also between suppliers. Another letter from Brown & Francis to Brown & Benson and Welcome Arnold notes that “a very Difficult man to Deal with, one Newel, is now in Town,” and he apparently is asking for more money for the lumber he supplies than the investors had agreed to pay. Brown & Francis in this instance ask their fellow investors whether or not they should pay him, demonstrating that when it comes to getting the most profit from their investment, the various vested interests were more than willing to work together.

One final, frequent concern that investors faced when putting together a voyage of this magnitude was that of keeping their information safe. Competition between investors representing different voyages was intense, and it was of utmost importance to make sure other parties had little knowledge of exactly what one was buying or selling, nor of the particular itinerary a ship was planning to follow (Nusco, 20 Oct. 2008). Evidently, the investors of the General Washington had one such scare, as John Brown consulted with Brown & Benson before sending a letter to one Joseph Butler emphasizing that “The Calculations made you by Mr. Jn B. is by no means proper to be seen Abroad”. The letter goes on to say that “the Apparant profits, or Secrets of the Voyage Ought not to be in everyones knowledge”. When operating at the scale of a voyage like that of the General Washington, privacy was essential, and the investors clearly did whatever they could to ensure no one would compromise their advantage.

Despite the trials and tribulations of preparing for the long journey to the East Indies, the partners eventually did get everything assembled and were ready to launch. The ship was captained by Jonathon Donnison and took two men, Samuel Ward and William F. Magee, as supercargoes who were solely concerned with the transporting and exchange of the ship’s goods (Hedges, Vol. 2, p.18). To bring the preparations for departure to a close, an invoice of goods to Madeira and India, dated December 22, 1787, was compiled. Five days later, the ship left Rhode Island’s shores.

In Transit

The General Washington’s first destination was in fact not the East Indies, but the island of Madeira, off the coast of Morocco. There the supercargoes traded a number of goods for Madeira’s most famous product, wine. Documentation of this wine was added to the aforementioned invoice and taken on to Pondicherry, India, where it was to be traded. The supercargo William Magee kept a wonderful journal of his travels, but its condition and length were unfortunately prohibitive to fleshing out all it could offer. Suffice to say, however, that by judging the many pages of the voyage that solely discuss day-to-day weather patterns, the voyage as a whole was rather uneventful. Yet, upon reaching India, the level of excitement increased in a rather disconcerting way for the investors. In a letter from Samuel Ward (in Madras) to Brown & Francis on August 19, 1788, Ward explains that he has had “the misfortune to find a great imposition in the quality of our wines which has proved a ruinous affair to the whole Voyage”. Meanwhile, William Magee describes in his journal his mistrust for the business practices in India and explains that he told Ward that he “thought his debauch [Indian tradesman hired to assist in selling goods] was a Great Villains and believed that he would Run away with the 90 Pagodas that [Ward] had given him.” In the end, though, the General Washington was able to sell some of its goods (albeit at a lesser price than expected) and made its way uneventfully to Canton, China (Hedges, Vol. 2, p.20).

At this early stage of development of the China trade, most American ships in Canton used their own supercargoes, partnered with a member of a Chinese trading group called a hong, to trade goods. In coming years the supercargo’s role would be replaced with a permanent American representative living in Canton (Hedges, Vol. 2, p.22), but for the moment Ward and Magee were responsible for trading the goods thus far accrued on the ship for Chinese goods bound for Providence. The major products brought home from China were tea, tea-related chinaware, and forms of cloth such as nankeens. The General Washington loaded up on these items and headed back to Providence, arriving home on July 6, 1789 (Hedges, Vol. 2, p.23).

Computations and Compromise in the Voyage’s Aftermath

While it was no doubt a joyous event to see one’s ship arrive home safely after being on the other side of the globe, it was also a time of high stress for any investor in foreign trade. While some lines of communication had certainly been kept between ship and home shore during the voyage, it was impossible to know for sure what goods would arrive home and how well they would sell in the local market. Brown & Francis, Brown & Benson, and Welcome Arnold all had a stake in the ship’s good fortune, but their personal interests also led to disagreements over the division of goods on board. This decision-making process, as it played out, is readily seen in two examples of the division of goods. One, the division of goods as of May 1789, displays the marks of numbers changing and even has a whole section crossed out. The second division of goods as of July 1789 is a much cleaner sheet with columns worked out with each investor’s haul.

The payment of workers from the ship is another issue the investors were required to address. While the Brown Family Business Records have numerous receipts of payment from all sorts of workers, a few examples suffice to show that, in general, a worker was given a certificate that he (and perhaps his son) had worked so many hours. The worker was then directed to take the certificate to one of the investors for payment. While it is possible that the investors had previously agreed on who would pay whom, it would appear from the sample of records in this part of the collection that the Brown & Francis firm had a habit of passing on this responsibility to the Brown & Benson firm. One must wonder if workers on trade vessels of this time often found it difficult to actually receive the payment they deserved for their services.

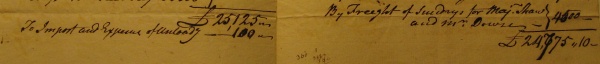

To close the chapter on this first voyage from Rhode Island to the East Indies, we look at a two-columned parchment of “proffit of loss by her Voyage to the Heather India”. The left column indicated an investment of £25,125 and the right a final value of £24,775.10 Rhode Island Lawful Money. This would indicate a loss on the voyage as a whole, but Hedges makes the claim the such estimates often exaggerate the costs (because the investors planned conservatively) and undervalue the profits (because some goods have not yet sold and actually sell for a higher price than expected; Hedges, Vol. 2, p.24). Given the fluid nature of most of the decisions observed up until this point in the documentary record, it is unsurprising that even these supposedly finalized accounts have a good amount of variability.

A Second Voyage by the General Washington to the East Indies—December 30, 1789 to June, 1791

Evidently the first voyage of the General Washington was successful enough in the eyes of its investors, for they quickly turned the ship around for another trip to India and China. This time, the ship would not stop to pick up Madeira wine, as another ship sent by the investors, the brig Providence, would be making that voyage simultaneously. It would be entirely appropriate to lump the information pertaining to this second voyage of the General Washington in with the first, as many of the same issues come up. Yet, for clarity of timeline and to highlight some key difference about this voyage, it is here analyzed separately.

Preparing for Voyage

Many of the same problems surrounding the preparations for the voyage were encountered in late 1789 as they had been in late 1787. One key addition seen in the historical record of this second voyage is the urgency with which Brown & Francis pushed the other investors to get their acts together in provisioning the ship. In a December 27, 1789 letter from Brown & Francis to Brown & Benson, the former firm informs the latter that they are “18 Cases Gin short supposing You pay your proportion…” As the tardiness of the first voyage to the East Indies contributed heavily to a reduction in profits (the General Washington received about half the price for the ginseng it sold as it would have received had it been one of the earliest ships to reach Canton; Hedges, Vol. 2, p.24), it is no wonder Brown & Francis press their fellow investors on this point.

The General Washington did successfully launch three days later, apparently with all goods accounted for, and headed once again to the East Indies. Its first port of call in the region was to be Bombay, India, where it arrived on June 7, 1790 (Hedges, Vol. 2, p.26).

In Transit

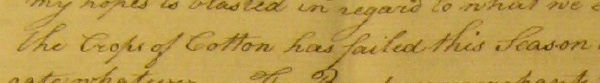

While the second voyage of the General Washington was, if anything, even less eventful than the first, events were again destined to be exciting once the ship reached the East Indies. Much less is known overall as to the events of the second voyage, but one thing that is well-known is that William Magee, the supercargo for the second voyage, discovered a failed cotton crop in Bombay. In a letter from Magee to Brown & Francis dated June 9, 1790, Magee explains that “the Crops of Cotton has failed this Season and there is none to be had at any rate whatever.” But he goes on to avow that because his orders from the investors are “binding me up to Sell at Bombay I shall Remain here, and shall soon be the only american bound to China.” Magee, faithfully carrying out his orders, ended up making a very fortunate decision. As he explains in subsequent letters on June 13 and July 16, 1790, the other ships bound for China went to other Indian ports in the hopes of finding better results, and he ended up staying just long enough to acquire the very last of the cotton in Bombay from the crop of the previous year. The General Washington was loaded with this cotton cargo and continued to Canton, where the cotton was exchanged for goods brought home to Rhode Island. Unfortunately for the historical record, there appears to be no list of exactly what was brought home on the second voyage to the East Indies (Hedges, Vol. 2, p.27-28).

Compromise and Sibling Rivalry in the Voyage’s Aftermath

By all accounts the second voyage of the General Washington was more profitable than the first. Yet despite this apparent good luck, there were still disagreements between the investors regarding the divvying up of goods. In what seems like an escalation from the aftermath of the previous voyage, the three primary parties had to call for arbitration of a dispute surrounding the sale of cotton during the voyage. Apparently, Brown & Francis had prescribed the cotton to be sold on a joint account among the investors, but Brown & Benson and Welcome Arnold felt the proceeds should be divided into their individual accounts. In the article of arbitration between the invested parties, each party, including the supercargoes of the General Washington (Magee) and Providence (Joseph Rogers), signs a pledge to abide by the decision of John Clark, William Russell, and Thomas Halsey. On the reverse side of this document (not shown here) is their decision: the cotton was and is to be considered as part of a joint account.

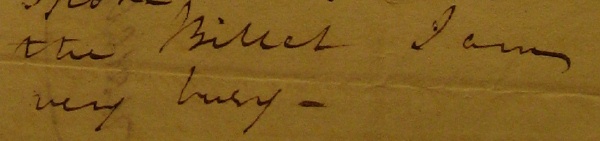

For the most part, the issues raised on the two voyages of the General Washington can be observed for virtually all international trading operations of this period. But in a letter from John Brown to Nicholas Brown in December of 1791, one gets a candid glimpse into how the brothers’ relationship may have played into their business dealings. Under the pretense of sending a letter from Brown & Francis to Brown & Benson, John Brown expressed his dismay that Brown & Benson would steal his carpenter to serve their company instead of his. The response from Nicholas is scribbled onto the back of John’s original letter and states that he knows nothing of this carpenter. He ends his reply by simply telling John, “I am very busy.” Clearly Nicholas Brown has not relinquished his position as older brother despite the separate business paths the two took.

Conclusion

The early voyages of the General Washington offer a rich portrayal of early American trade with the East Indies and highlight many of the challenges faced by American business investors in any market or industry. While subsequent voyages to China would see Brown & Francis and Brown & Benson fund their own individual ships (Hedges, Vol. 2, p.28 & 30), the lessons learned from their joint ventures would prove valuable in their future successes and failures. It is important to note that the scope of the American East Indies trading industry paled in comparison to that of Britain, but clearly such cooperative ventures as those of the General Washington helped establish an American foothold in the market.

The Brown Family Business Records offer a wealth of information beyond the scope of this project, and anyone interested in learning more about the social context of early American business would be want of a better resource. Many thanks are due to Kimberly Nusco and the rest of the staff of the John Carter Brown Library for their help in making sense of the vast resources available therein.

Bibliography

Hedges, James, The Browns of Providence Plantations: The Nineteenth Century. Providence, Brown University Press, 1968.

Nusco, Kimberly. Personal interview. 20 October 2008.

Primary Sources

“John Brown's Proposal for Brown & Benson to Purchase a One Eighth in the General Washington”, B.546 F.7, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

“Letter from Brown & Francis to Brown & Benson and Welcome Arnold Condemning Their Suggested Withdrawal from Investment in the General Washington”, B.546 F.7, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

“Letter from Brown & Francis to Brown & Benson and Welcome Arnold Regarding Difficulties in Negotiating with Lumber Salesman”, B.546 F.7, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

“Letter from Investors of General Washington to Joseph Butler”, B.546 F.7, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

“Invoice of Goods Sent to Madeira and India on the General Washington, dated December 22, 1787”, B.547 F.2, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

“Journal of William F. Magee”, B.737 F.3, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

“Letter from Samuel Ward (in Madras) to Brown & Francis on August 19, 1788”, B.546 F.8, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

“Preliminary Division of Returning Goods on the General Washington as of May 1789”, B.546 F.8, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

“Finalized Division of Returning Goods on the General Washington as of July 1789”, B.546 F.8, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

“Examples of Payment Receipts for Returned Sailors Aboard the General Washington”, B.546 F.9, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

“Profits and Losses of the First Voyage to the East Indies by the General Washington”, B.546 F.9, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

“Letter from Brown & Francis to Brown & Benson Regarding Delay in Supplying the General Washington, December 27, 1789”, B.547 F.2, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

“Letter from Magee to Brown & Francis Regarding Failed Bombay Cotton Crop, June 9, 1790, and Subsequent Letters of June 13 and July 16, 1790”, B.547 F.3, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

“Article of Arbitration between Brown & Francis, Brown & Benson, and Welcome Arnold Concerning the Selling of Cotton by the General Washington”, B.547 F.3, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

“Letter from John Brown to Nicholas Brown Regarding Stealing of Carpenter, December, 1791”, B.547 F.3, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

Back to Social Contexts | Historical Climate and Connections: Shipping and the Browns