(Conley 1992, 102)

(Conley 1992, 102)

Landscape Contexts: Introduction

A survey of maps of Providence since the 17th century tells a story of changing ownership, changing land use, and ever-increasing population and development. The Brown family and the John Brown House occupied a culturally and economically central place in these changes. We look below at early maps of the area, showing the building of the house in a prestigious up-hill area of Providence, overlooking the shipping trade responsible for the Browns’ fortunes. We consider the retrospective maps drawn by 19th and 20th century historians to relate the Providence of their times to the earliest European settlement. Finally, we discuss trends in Providence’s development since the late 19th century and see them reflected in the increasing detail and accuracy of maps since that time.

Early Maps (1770-1803)

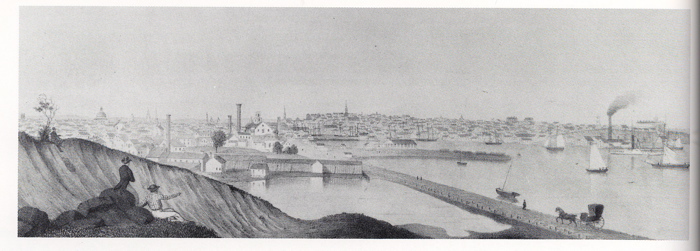

Early depictions of Providence give us an excellent impression of the dynamic city in which the John Brown House was built. The earliest prints of the city are mainly plats from the 18th and early 19th centuries. Plats were small maps that clearly marked out property boundaries. One of the early plats that delineates property belonging to the Brown family is a plat from 1746 that shows the division of land along Towne St. (which is now North and South Main.) However, after plats, the first comprehensive views of Providence can be found in the 1770 powder horn map and 1790 Fitch sketch. Though these maps are not accurate to scale and therefore exclude some buildings and landmarks, they do represent the first full views of Providence that include approximate drawings of settlement patterns, waterways, and roadways at the end of the 18th century. The 1803 Anthony map, the first made from an actual geographic survey, is an example of the increasingly detailed survey methods that developed as the young U.S. government began documenting the states. Finally, Artist John Warrell’s depiction of the city around 1810 fills out our collection with a landscape-style view of the increasingly developing city. This painting gives us an impression of Providence not from an imaginary bird’s eye view, but from a human’s point of view across the waterfront.

The 1746 plat shows dense settlement along the waterfront with wharves, houses, and churches interspersed with some undeveloped lots. Among the buildings listed are Brown’s Cooper Shop, Capt. Brown’s House, and Capt Brown’s Wharf, all of which are North of the John Brown House property, near College St. Later maps place Chad Brown’s home lot here. (Chad Brown was John Brown’s great-great-grandfather, and the first of the Brown family to settle in Providence.)

In both the powder horn map and the Fitch map, Towne St. is the most densely settled area of Providence, with only a few roads branching off up College Hill and across the Providence River. The powder horn map was carved by a Revolutionary War soldier named Stephen Avery in 1777. This places it as the earliest technical comprehensive view of Providence, although the first paper map was drawn by Brown University student John Fitch in 1790. And while the John Brown House does not appear on the 1777 map as it hadn’t yet been built, the mapmaker’s drawings of tall ships under full sail and smaller boats crossing the river do hint at the atmosphere of growing trade and the prosperity in Providence in the 18th century that would in time build the Brown family fortune and allow John Brown to build his house on Benefit Street.

Strikingly, the powder horn and Fitch maps both face east, rather than north as convention dictates. Even though settlement is densest along the riverfront, the mapmakers see the focus of Providence as eastward and up the hill. College hill was the area first divided among settlers as the “home lots” and continues, today, to be home to powerful Rhode Islanders and Rhode Island institutions. The panoramic view up College Hill that John Worrall painted between 1808 and 1812 continues this story of dense settlement around the river. The focus of this landscape still faces east towards the hill, where new roads and grand buildings continue to appear. This is quite logical when one considers that trade via sea was the staple of the Providence economy; therefore, the hill was an excellent vantage point from which merchants could watch for their ships returning. The hill was a practical place for the wealthy merchants to build their houses, and as a result, owning a house here became symbolic of wealth and power.

It is in this powerful neighborhood that the John Brown House appears on the Fitch map, one of the few eastward buildings drawn, along with Brown’s University hall. The Fitch map was drawn just two years after the John Brown house was built. The Anthony map shows us that by 1803, the Browns shared this area with Governor Fenner, whose house is shown a few blocks from the John Brown House, along present-day Governor St. The 1803 map also shows the continued development of Providence, with new roadways appearing in the College Hill and Downtown areas. Benevolent St. and a street in the current location of Brown St. have cut through some of the open area previously surrounding the house.

Maps of Providence drawn just before and after the John Brown House was built show the changing landscape around the property as the city’s population grew and Providence became increasingly urban. Through the inclusion of specific buildings, illustrations of significant motifs in Rhode Island society, and choices of perspective, these maps are indicative of the Brown family’s prominent place in Providence society.

Retrospective Maps of Early Settlement

Perhaps the most intriguing views of Providence and College Hill in the 17th century come not from contemporary maps, but from maps drawn two to three hundred years after the time they depict. These maps may not be entirely accurate representations of colonial Rhode Island’s geographic layout, but they are fascinating reflections of social, economic and cultural perceptions about the developing Providence of the 17th century from an early 20th century standpoint.

The Hopkins map was created in 1886, on the 250th anniversary of the founding of Providence. This map (either intentionally or not) manages to integrate the original settlement and ownership patterns with the author’s own contemporary landscape of Providence. The author placed home lots in relation to naturally occurring geological features while still aligning them with the streets that exist in 1886. For example, Hopkins’ map connects Power Street with the abutting property of settler Nicholas Power. Additionally, Hopkins relates all of College Hill to the first European settlement in Providence. Many street names echo the names on plots of original settlers that Hopkins has drawn into this hybrid map. A “Thomas Hopkins” (perhaps a forebear of the author himself) also appears on the map, serving to further connect the Providence of the 17th century to a Providence aged by two and a half centuries. It is bridges like these that force the reader to acknowledge the physical human connection between the names we have assigned to these spaces, and the people who originally lived there. These people inscribed their own names upon the landscape, serving to memorialize themselves far longer than perhaps they ever expected. And the 1886 map is not the only example of this; the cartographers who created the various retrospective maps throughout the 20th century made the same attempt to align his or her perception of Providence with the Providence of centuries past. This map does not mix the past and present but instead shows the change of Providence’s profile in two distinct snapshots. Shadows of modern streets behind the home lots and an outline of the original path of the Providence River create a palimpsest of past and present to show two clear views of Providence, centuries apart.

These retrospective maps of the home lots both show that the site where the John Brown House now sits was originally part of the property of William Wickenden. Chad Brown, the great –great-grandfather of John Brown, is represented by a lot near the present location of College St. and parts of Brown University. The maps do not show buildings in this area, which reinforces imagery from the earlier maps. The most developed area of Providence at this time would have been along the waterfront, as evidenced by both earlier plats and the more comprehensive maps. Larger-scale retrospective maps that look back at all of Rhode Island are filled with notes and comments about land disputes between European and Native American groups, and among municipalities. This shuffling of land mirrors the continuously evolving plots in Providence as wealthy traders bought and sold lots, including the lot where the John Brown house now stands.

The retrospective maps that were made in the 19th and 20th centuries to depict the Providence of the 16th century emphasize a connection between original settlement periods in Colonial Rhode Island and later periods in the history of the College Hill neighborhood. Looking at the maps emphasizes the history of power and privilege in an area that remains one of Providence’s wealthiest, and is also a testament to the power of Providence as the seat of government for a small yet wealthy state in a young and growing country during this time.

Trends in Maps of Providence Since 1803

The Daniel Anthony map of 1803 was the first accurately surveyed map of Providence. It shows the existing streets and waterways of the time and their relationships to each other on a very precise and accurate scale. Since 1803, maps of Providence have become increasingly detailed as technology required to collect this type of survey data has improved. At the same time, the landscape has been aggressively developed; the creation of roads to increase ease of transport and buildings to house burgeoning industries has even changed the face of Rhode Island’s coastline drastically. The area around the John Brown house was once an open hillside of fields; now, it has been built in and up, and skyscrapers rise from downtown Providence to dwarf the hill that was once the highest point in Rhode Island.

By 1885-1887, a USGS topographic map shows us the layout of streets around the John Brown House that are familiar to the 21st century residents of College Hill. The riverbank has been built up to such an extent that the river is hardly recognizable as the sizeable, bustling trading port that Providence of the past, with wharves along west shore of what used to be a wide river mouth. Four buildings are pictured on the John Brown House property, although none of them appear to be over where we are currently excavating.

In the Haley photograph from 1931, and Cady’s 1942 map, we can see the development of railways and taller buildings downtown. The highway has not yet been built over the old wharves on the western bank of the Providence River, but there are new wharves growing up further out in the harbor. In this photograph and map, the John Brown House sits in the middle of a residential area packed with tree- and house-lined streets.

According to the 1957 USGS map, highways have begun to transect city and river, and the waterfront has been fully transformed into the coastline that we recognize today. The area around the John Brown House has continued to grow as a wealthy residential area, sharing space with colleges and churches, but little else. There are few commercially dedicated buildings in this area.

Over time, maps of Rhode Island from the 19th and 20th centuries show the rapid industrialization and development of Providence, and then the evolution of the area around the John Brown House away from an industrial center and towards a gentrified residential area. The city continues to grow and expand today, and so maps have also changed drastically to reflect this. Now, one can simply log onto the Internet to pull up a satellite image of Providence as it exists in this exact moment.

Landscape Contexts, Continuity, and Change

The John Brown House property, its College Hill surroundings, and the maps used to describe them have changed substantially over the past 400 years, and the changes in these three areas reflect each other: the property has continually changed hands and has changed its use from an open field to a grand residence to an educational museum. Similarly, Providence has given up and re-annexed land from its surrounding municipalities, and has seen an ebb and flow of industrial activity.

Still, the continuous settlement of the area since Providence’s earliest days has been used to connect the city to its colonial past, and the John Brown House is used by the Rhode Island Historical Society in much the same way. The graphical record of College Hill’s history reflects seemingly opposing values: early Rhode Island’s pre-capitalist facility with shifting land ownership contrasts with later Rhode Island’s desire for historical and cultural continuity and preservation.

Works Cited

Cady, John Hutchins. "Walks Around Providence." The Akerman-Standard Press; Providence, RI.: 1942.

Conley, Patrick T. "An Album of Rhode Island History, 1636-1986" The Donning Company/Publishers; 1992.

Gibson, Susan G. "Archaeological Resource Study: Roger Williams National Memorial, Rhode Island." 1979.

Haley, John Williams. "Providence Illustrated Guide." Hayley & Sykes Company; Providence, RI.: 1931.

Hopkins, Charles Wyman. "The Home Lots of the Early Settlers of the Providence Plantations, with Notes and Plats." Providence Press Company; Providence, RI.: 1886.

Full size maps can all be downloaded here