On shamanism and the materiality of images

Omur Harmansah

A response to Discussion Week 2: Sept. 15. Body in recent critical/social theory

Posted: September 21, 2006 Thursday 12:12 pm.

Alfred Gell proposes that he sees “art as a system of action to change the world rather than encoding symbolic proposions to it.” (Art and agency: an anthropological theory, Oxford : Clarendon Press ; New York : Oxford University Press, 1998: 6). It is interesting that what he is primarily attempting to do is to rescue artifacts, things and works of art from the interpretive paradigms of canonical art history, of especially Panofskian structuralist iconographic approach and Gombrichian psychoanalytic readings, which would like to see works of art primarily “representational” therefore passive in the constitution of the social world. Traditional art history persistently denies the ontological groundedness and agency of works of art, reducing their meaning to their representationality and narrativity, but turns a blind eye to their active participation in the social world. Works of art are always afterthoughts, they are visualizations, “fixing”s, narrativizations of ideas, events, and other worldly phenomena long after the social action takes place. A portrait of a German princess is, by that definition, represents the German princess more or less truthfully, and provides a good resource for studying the inner and outer self of this princess, the artist who depicts her, and their encounter. The making of the portrait is rarely considered as effective in the constitution of the subjectivity, the identity of this princess. Processual archaeology was heavily influenced by such art-historical understanding of artifacts and things as passive and informative, not active and performative.

Image Credit: Portland (OR) Art Museum website. Landgräfin Anna of Hesse (born Princess of Prussia) , 1858, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, oil on canvas. From the exhibition "Objects of Hesse: a Princely German Collection"

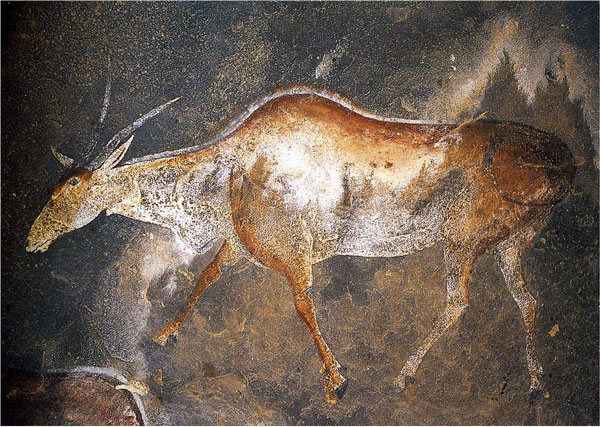

The so-called rock-art images from France, Spain, South Africa and elsewhere have taken their place in the first pages of art-historical survey books with a similar premise: they were representations of the most important events in the life of the Palaeolithic men in their endless struggle to survive. Departing from the newly flourishing, theoretically invigorated field of material culture studies, new interpretations of rock imagery are now focusing on the materiality and agency of these images, through which individuals constituted their social life. David Lewis-Williams’s shamanistic interpretations of South African San rock paintings suggest that such images are “storehouses of potency” or “reservoirs of n/om” through which San societies established active links with the spiritual worlds. A depiction of an eland on the rock surfaces can not be reduced to a representation of an animal, but should be understood as a powerful entity which in certain ritual contexts become a spirit-filled being that emerges from the spiritual world, on a surface that constitutes the boundary between different worlds. The long and arduous process and technologies of the acquisition of pigments and the making of the images confirm the potency of the images, and the way that the images are continously touched by bodies in need of healing emphasizes their materiality. The complexity and ritualistic processes of the making of the images would be known by all collectively, so that magical/potent qualities would be unquestionable.

Image Credit:

What is particularly revealing in Lewis-Williams’s work is the identification of the making of rock image as a part and parcel of shamanistic practices that involve embodied social performances, altered states of consciousness essential to the well-being of the society. The rituals are not only cathartic for the society but they frequently aimed at healing of troubled individuals. In the healing rituals, the shaman “sees into the body of the patient” whose body becomes penetrable to the shaman. During such healing rituals, the limits of the body, its taboo boundaries, the skin between the interior and the exterior becomes permeable, the bodies become fluid: sickness flows from sick people to shamans, just as potency flows from images to those who touch them. This, in my mind, itself is a critique of the Western notions of body as a bounded entity with a clearly defined and tabooed boundary: the skin. The fluidity of the bodies however seem to become possible only during such altered states.