Questions, ideas, notes for discussion:

- I've been reading Alexander's lengthy piece on social performance, which I have found intriguing as well as disappointing at times. His analytical study of performance by breaking it down to its fundamental components (actors, audience, mise-en-scene, material means of symbolic production and social power) is really helpful I think in not reducing performance to actors, audiences and scripts but incorporating social space and material things and their socio-symbolic frameworks. The discussion of the foregrounded script (dispositions) versus collective representations (socio-symbolic structures/habitus) was also interesting, and I think will be useful for us. However, when he attempts to historicize social performances in the ancient contexts of ritual and theater (and in relation to social complexity), he is surprisingly and worryingly using an really outmoded (and largely discredited) paradigm of the axial civilizations, situating historical consciousness and self-reflexivity only among those "axial" civilizations (i.e. 5th century Athens, Late Iron Age Israel, Early Christian Europe etc) which assumes a "despotic" nature to all "pre-axial" cultures such as Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt. I'd be interested to hear your reflections on this. I hope we will be able to unpack all of this a bit in class tomorrow.

- I am also hoping that we can use Alexander's model of the foregrounded scripts/collective representations to look at the Uruk Vase that Bahrani and Pollock/Bernbeck articles are talking about. And the question of how can we consider such powerful objects such as the Uruk Vase (with its representational force) as performing and taking a role in social performances. I will give a brief historically contextualizing presentation on Late Chalcolithic Uruk where the vase was found, and a quick overview of the discussions of increasing social complexity (invention of writing, urbanization, administrative tools, craft specialization etc) in that historical context. Kerry's presentation of the Sacred Marriage ritual will perhaps help us to locate the vase even in a more specific cultural context between prescribed, fixed forms of social action and more loosely defined, unbound ritual performance in the ancient Near East, highlighting the debate over how to read the vase.

- I have assigned a small paper to my Archaeology of Mesopotamia class a paper on the Uruk Vase. Very productive results indeed. One of my students Emma Maines wrote that “perhaps the vase was designed to visually narrate or visually allude to the story of the ceremony for which it was created as an offering to the goddess Inanna. In this manner, the vase would promote ritual by ritualizing itself.” Fascinating idea. I added to this comment that the vase performatively asserts its own presence through the symbolic act of representation; it becomes a powerful agent of the ritual, by virtue of its abduction of the authorship of its making. And therefore it celebrates, commemorates its own making. Whoever the craftsman who produced the vase: he is subdued, leaving the vase to claim its own poiesis. What do you think? Can we make use of Gell's theory of agency in this case?

- My favorite sentence from Gell: "I view art as a system of action intended to change the world rather than encode symbolic propositions about it" (6). Very performative understanding of artifact production and material culture indeed, and makes Panofsky-adoring art historians angry. Should we open this can of worms on materiality? I think we should.

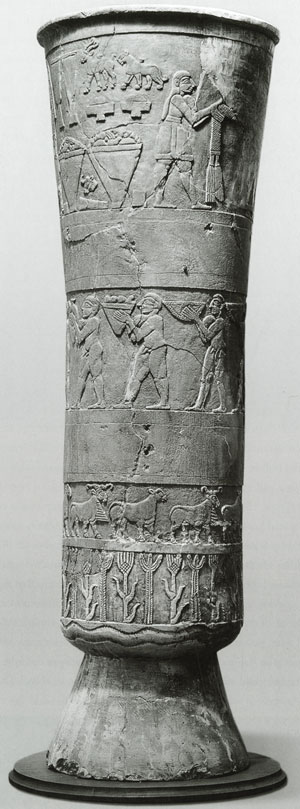

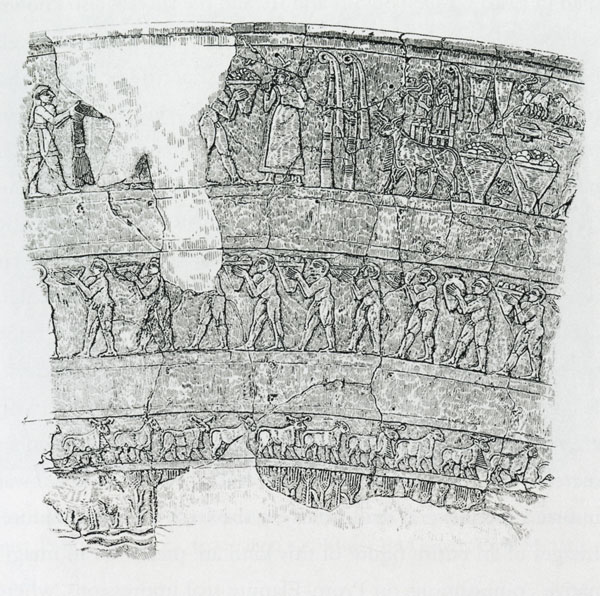

Images of the Uruk Vase

Uruk (Warka) Vase. Relief carved, alabaster. Late Uruk Period (3300-3000 BC). Iraq Museum, Baghdad. Inv. IM 19606.

Image Credit: Aruz, J. (ed.); 2003. Art of the First Cities. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Fig. 9, p. 24.

Uruk (Warka) Vase, drawing. Relief carved, alabaster. Late Uruk Period (3300-3000 BC). Iraq Museum, Baghdad. Inv. IM 19606.

Image Credit: Aruz, J. (ed.); 2003. Art of the First Cities. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Fig. 10, p. 25.