Agrigento (Akragas)

Agrigento, also known as Akragas, was a Sicilian apoikia founded in 582 B.C.E. The Rhodio-Cretan founders, led by Aristonoos and Pystilos, came from Gela, another Sicilian apoikia that had been established around 688 B.C.E and that was flourishing by the mid-6th century. The city was ruled by an oligarchic government, and saw a succession of tyrants in power. It was under Theron, the third of these tyrants who came to power in 488 B.C.E, that Agrigento reached its political and military peak. This height of military power was marked the defeat of the Carthaginians in 480 B.C.E, in which Theron was allied with his brother-in-law, Gelon of Syracuse. The victory prompted a grand building program in Agrigento that included the Temple to Olympian Zeus and the construction of a system of aqueducts designed by the architect Phaiax.

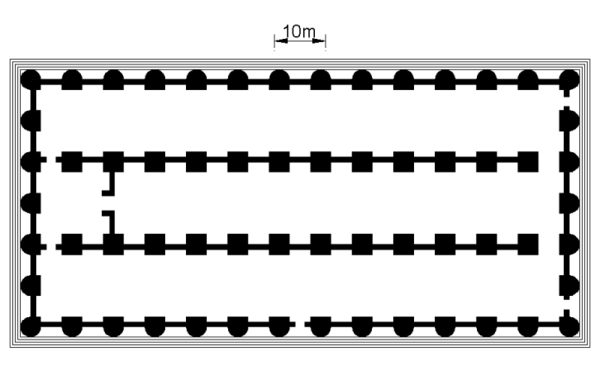

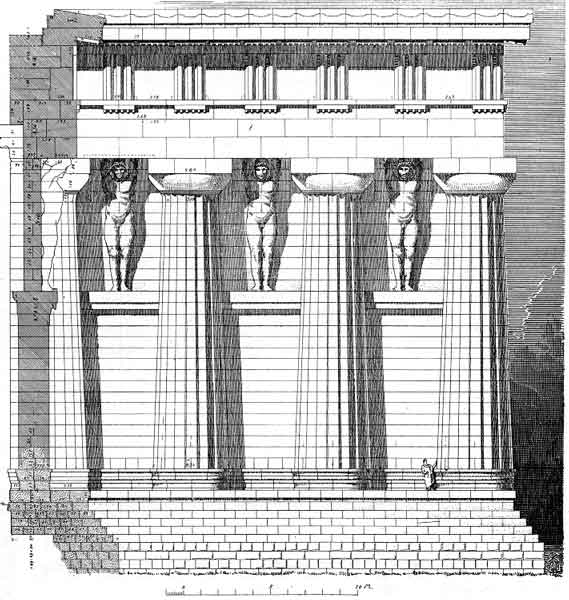

The Temple of Olympian Zeus at Agrigento was the largest temple built in the Greek world, with a ground plan measuring 340 x 160 feet, and a height of 120 ft. The historian Didorus Siculus describes its immensity, stating that a human figure would be able to fit into each of the flutings on the columns. It was a temple in the Doric order, but diverged from the standard design that had been established for Doric temples by this time. The most striking feature is that ashlar walls with Doric half columns at regular intervals replace the traditional colonnade, as can be seen in the ground plan (Fig. 1). In the interior, Doric pilasters are positioned to reflect the half columns of the exterior, and a very different effect is created with substantially less natural light and air than in the traditional design. Another defining feature of the temple is the positioning of colossal telemons mid-way up the exterior walls between the half columns (Fig. 2). Their position, with their arms and necks bent, is such that they seem to be supporting the architrave of the temple. They were 7.65 metres tall, and their method of construction can be seen in Figure 3. It is thought that the temple was hypaethral, that is, open to the sky, due to the difficulty in constructing a roof to span the distance. However there is no evidence either way. We also do not have evidence of the sculptural decorations on the facades that were supposed to depict the fall of Troy and the Gigantomachy (the battle between the gods and the giants). The ambitious nature of the temple meant that it was left unfinished at the time of the Carthaginian destruction of Agrigento in 406 B.C.E.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Two other temples in Agrigento are the Temple of Concord and the Temple of Herakles. The Temple of Concord was built around 430 B.C.E along the popular design of 6 columns by 13. The columns, entablature and pediments remain intact today, and this exceptional level of preservation is due to the use of the temple as a Christian Church to St Peter and St Paul. Due to the adaption of function, the inner layout of the temple’s cella, pronaos and opisthodomos no longer exists. The Temple of Herakles is Agrigento’s oldest temple. It is datable to the end of the 6th century due to the shapes of the columns and capitals and the older Doric layout of 6 columns by 15.

Another important find at Agrigento is a kouros figure, dating to around 480 B.C.E (Fig. 4). It is reminiscent of the Kritios Boy, although the pose is freer, with the arms detached from the body. The surface is also highly polished, perhaps to imitate the smooth finish of bronze sculpture.

Figure 4

After the razing of Agrigento by the Carthaginians, the city lay abandoned for decades until around 338 B.C.E, when the tyrant of Syracuse defeated Carthage and restored peace to the Sicilian towns. Agrigento was then rebuilt, and subsequently saw a variety of rules, including the Carthaginians and eventually the Romans in the 3rd century B.C.E.

Bibliography

• ‘Akragas’-The Princeton Encyclopaedia of Classical Sites (edited by Richard Stillwell, William L. MacDonald , Marian Holland McAllister)

• http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/ (Perseus Building Catalogue)

Posted at Dec 11/2007 10:12PM:

keffie: Great connections!

Posted at Dec 13/2007 11:31PM:

Harry Anastopulos: The sheer size of the Western Greek temples is overwhelming! The Greek temple taken to a new level, for sure. I'm actually headed to Italy this summer...if we head south, Agrigento will definitely be on the list...

Posted at Dec 16/2007 10:10PM:

Kuy Yeon Lee: I love the figure 3 picture. Really, I'm also impressed by the size. Hope I could visit there soon. Your project also has been very helpful for the final. Thanks so much!! =)

Posted at Dec 17/2007 07:53AM:

Rachel Griffith: Your description of the Temple of Olympian Zeus was really useful. Its unbelievable that a person could fit into a single fluting-- we are so used to the smaller scale that we usually see in Neoclassical Greek styles. I also never noticed the person drawn into figure 2 before, it does show the enormity of the scale.